Therapeutic colonoscopy is an invasive procedure that can involve complications. Here we report the case of a man who presented with an abdominal wall abscess after having an endoscopic polypectomy. This article describes a rare form of colonoscopic perforation and suggests conservative management as a viable treatment option.

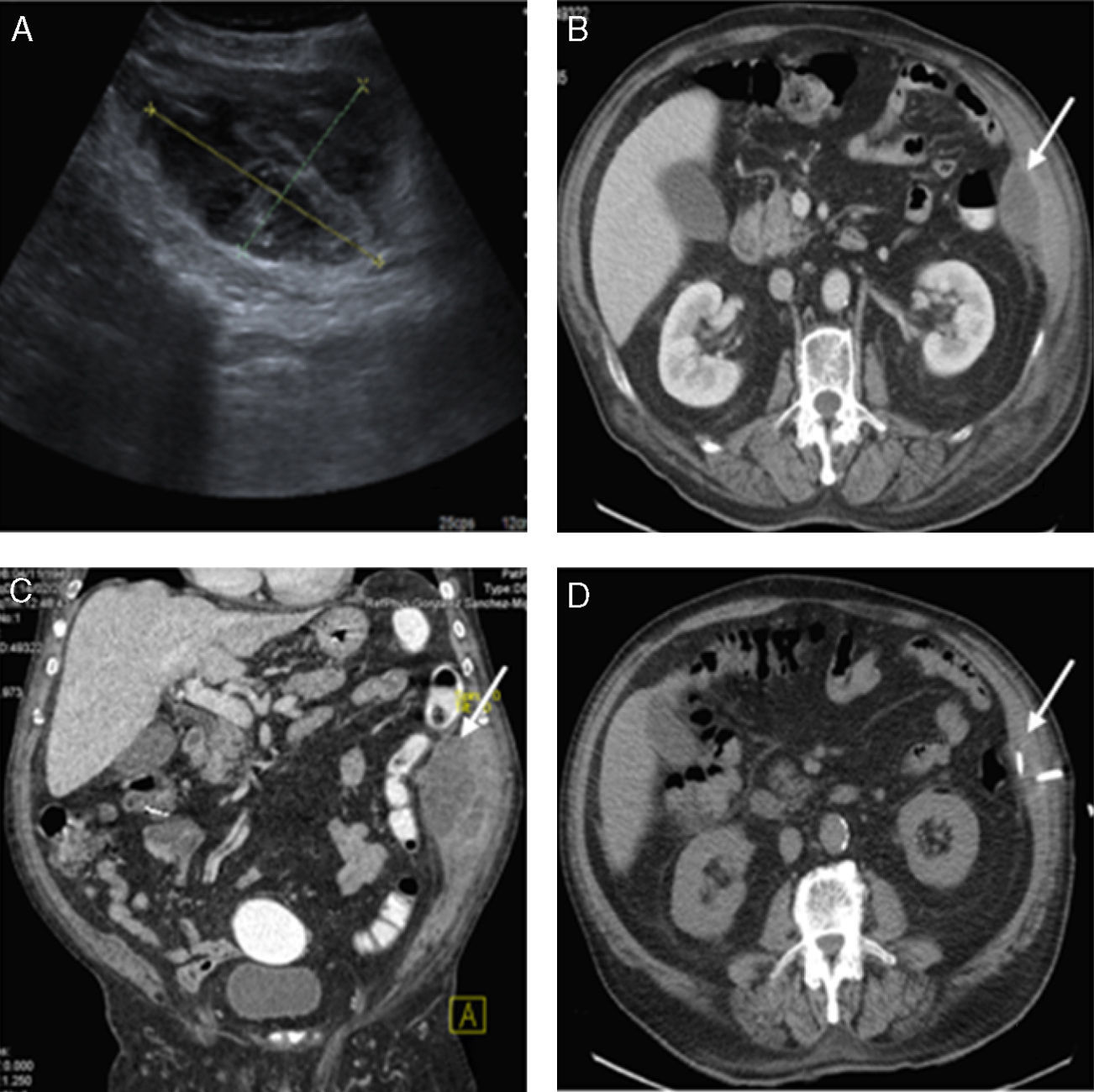

A 73-year-old man who underwent a colonoscopy during which 2 polyps of 5 and 6mm were excised with diathermy loop from the ascending colon, one of 5mm from the transverse colon, and others measuring 2–40cm and 30cm in the anal margin, 12mm and 9mm, respectively (all type I according to the Paris Classification). Adrenaline was used as a sclerosing agent on all of them (diluted at a ratio of 1:10,000 in physiological saline), and clips were applied to the scar tissue of the larger polyps (12 and 9mm), with the wounds being well closed on visual inspection. Two weeks later, the patient went to the A&E for left flank pain and fever. An examination revealed an abdominal wall tumor there, with associated cellulitis and fluctuation, with the rest of the abdominal examination showing no pain. An ultrasound showed a hematoma 4.2×9.1×10.3cm thick on the transverse abdominal muscle (Fig. 1A). An abdominal CT was requested with intravenous and rectal contrast agents (Fig. 1B and C), which showed a hypodense collection with peripheral enhancement located in the left lateral abdominal wall, which retracted medially to the parietal peritoneum. It was in close contact with the descending colon proximal to the one that displaced it; no connection with it or contrast leak from the colon to the abscess was identified. The abscess was drained with a CT-guided radiological catheter, with a purulent, malodorous and chocolate-colored material being obtained. A culture of the material isolated Escherichia coli, Klebsiella oxytoca and Proteus mirabilis. The patient was admitted for surgery with piperacillin-tazobactam given as an empirical intravenous antibiotic. His progress was favorable, with the fever and the external signs of infection disappearing. Bowel transit time and oral tolerance were appropriate throughout the process. Drainage was withdrawn due to a low flow prior to the radiological check (Fig. 1D), and the patient was discharged after 6 days.

(A) Abdominal ultrasound: abscess 4.2×9.1×10.3cm. (B) Abdominal CT with IV and rectal contrast agents (axial plane): hypodense collection with peripheral enhancement located on the lateral abdominal wall (white arrow). (C) Abdominal CT with IV and rectal contrast agents (sagittal plane): the abscess described in B (white arrow), with no rectal contrast leak. (D) CT-guided radiological drainage of the thickness of the abscess.

In addition to the complications from diagnostic colonoscopy, the complications from polypectomy include other adverse events directly related to the polypectomy, such as acute or late-onset bleeding (0.65%), perforation at the site of the polypectomy (0.06%) and postpolypectomy syndrome, also known as transmural burn syndrome. The rate of serious complications exceeds 2.3%.1 Although there is an isolated case reported of a retroperitoneal abscess,2–4 according to a comprehensive review of the literature (Medline and Embase databases), we believe that this is the first case described in Spain of an abdominal wall abscess, which was resolved conservatively, thus avoiding surgery, and with a good clinical outcome.

On this occasion, the diagnosis of an abdominal wall abscess was based on the clinical and radiological evaluations. It seems reasonable to associate this abscess with a colon perforation due to the presence of enterobacteria, which suggests its intestinal origin. In addition, there were no other coincident causes of retroperitoneal or parietal abscess, such as diagnostic or therapeutic ureteral stone manipulation or trauma. Most likely, after the polypectomy, a micro-perforation of the lateral retroperitoneal space occurred that caused the abdominal wall abscess, with no free perforation taking place. This is reflected by the order in which the clinical events happened.

The literature, with more evidence coming in each day, reports that the removal of polyps of more than 2cm is one of the main risk factors for perforation.5–7 Risk factors also include a short pedicle and an excessive transmission of heat or necrosis beyond the base of the polyp when performing electrocoagulation techniques. Although the risk is greater in the right colon (since the wall there is not as thick), the most common site of endoscopic perforation is the sigmoid colon.6,8 Most of the perforations are intraperitoneal, with clear clinical signs and pneumoperitoneum. They usually occur and are discovered during the colonoscopy or during the first 24h following the procedure. By contrast, extraperitoneal perforations are less common, and as with our patient, the clinical symptoms are usually mild or absent. There are also late-onset perforations, which result from thermal damage to the submucosa, and which may progress to transmural lesions over time, because the adipose tissue of the mesentery or omentum partially covers the defect. This late-onset damage is less pronounced and has fewer clinical effects.

The management of colon damage after colonoscopy is still controversial. If the damage is identified during the procedure, the size is not too large and the patient's condition permit it, the closure of the lesion can be attempted using clips. If clips are not suitable for closure, or the scar tissue is too large in size, the OVESCO system might be used. This system closes lesions more effectively by grasping 2 or 3 of the layers of the wall (compared with the clips, which only involve the apposition of mucosa to mucosa), thus allowing for a more precise closure.9 In contrary circumstances, the patient should be transferred to surgery for urgent surgical treatment. Since in our case the complication was unusual, we found no references on how to manage it. A high clinical suspicion, accurate diagnostic tests and interventional radiological management are the 3 fundamental pillars for the satisfactory resolution of this adverse event.

Please cite this article as: García-García ML, Jiménez-Ballester MÁ, Girela-Baena E, Aguayo-Albasini JL. Colección abscesificada en pared abdominal secundaria a polipectomía colonoscópica. Manejo radiológico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:463–464.