Most of the cirrhotic patients develop portal hypertension in the course of the disease. It is estimated that esophageal varices are present in more than 30% of patients with compensated cirrhosis and approximately 60% with decompensated cirrhosis.1,2 The most important predictive factors of the variceal bleeding are the severity of the liver dysfunction (Child B-C), large variceal size and the presence of the red wale marks. The current consensus suggests that an endoscopy for variceal screening should be performed to every patient who is diagnosed with cirrhosis. This recommendation is made to identify which group of patients needs prophylaxis treatment.3 For the prevention of first variceal hemorrhage, in patients with cirrhosis and small varices with red wale marks or Child–Pugh C, nonselective beta-blockers should be used but in patients with medium–large varices nonselective beta-blockers or Endoscopic Variceal Ligation (EVL) may be recommended. EVL is a safe technique for the treatment of acute variceal bleeding and for the primary prevention of hemorrhage and rebleeding in patients who suffer from portal hypertension, considering sclerotherapy an alternative endoscopic method.4,5

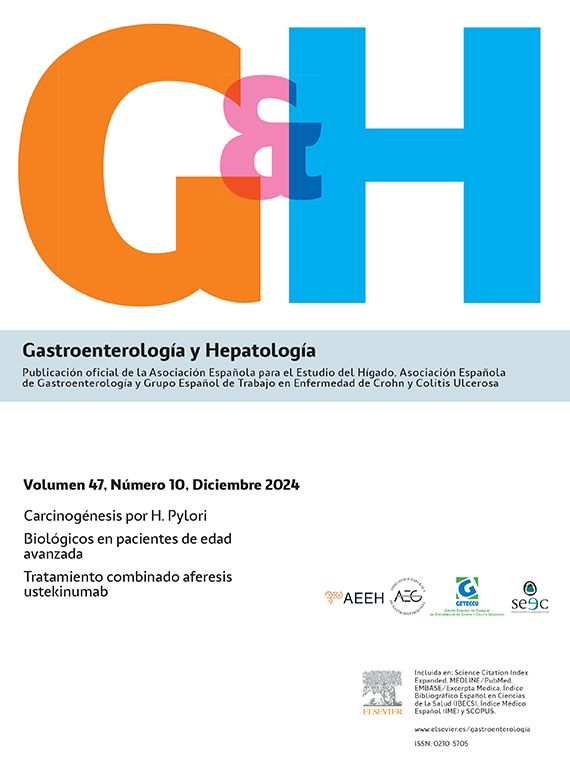

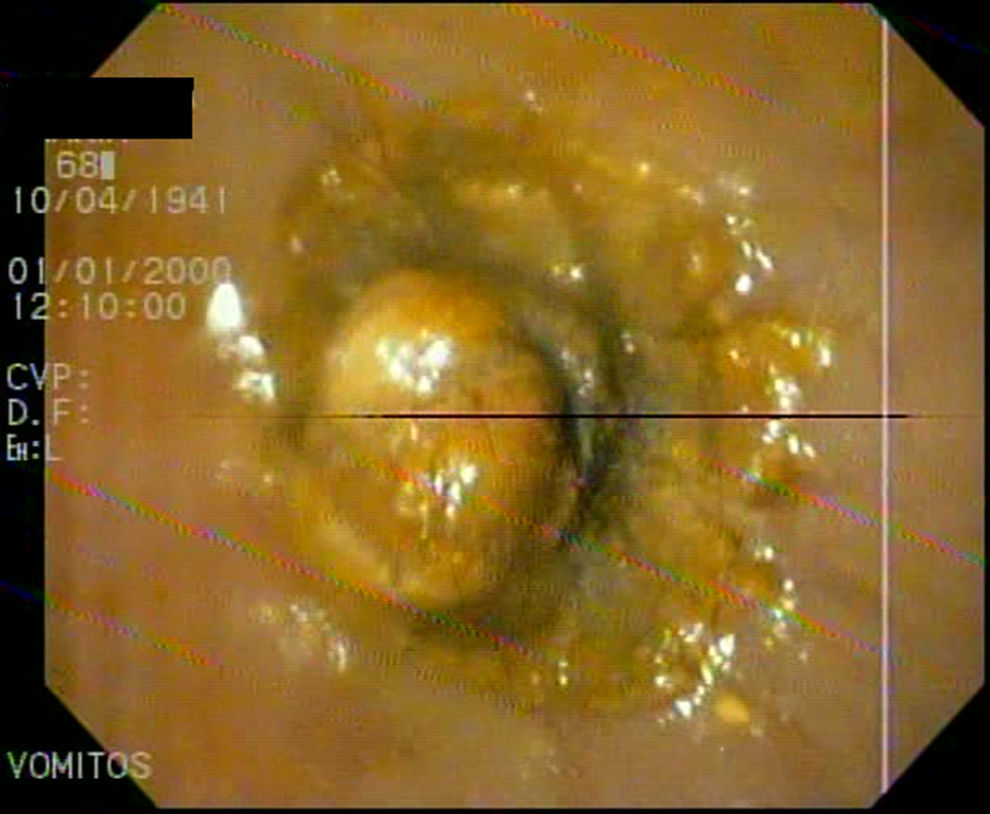

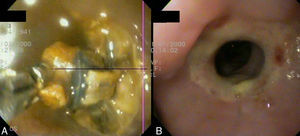

We report a case of a 65-year-old woman with a medical history of Child–Pugh A cirrhosis owing to hepatitis C virus and no hepatic decompensation who had large esophageal varices secondary to portal hypertension. The patient stopped beta-blockers due to side effects. She had three sessions of EVL. Two days after the third session, she went to hospital because she had vomits at home after the banding procedure. Those vomits persisted despite the administration of prokinetics. The patient was lucid, afebrile, haemodinamically stable and with normal oxygen saturation. Therefore, it was decided to perform an upper endoscopy. Food debris and a total esophageal obstruction were found in the lower third of the esophagus due to a band wrapping the entire circumference and causing ulcerated mucosa in that place (Fig. 1). In order to unblock the esophagus, we tried to push down and carefully remove the band with forceps without any success (Fig. 2A). We adopted expectant behavior and decided to hospitalize the patient in a medical clinic room and start the intravenous hydration. Forty-eight hours later, the patient was able to swallow liquids, so the next day a follow-up endoscopy was performed observing a circumferential ulcer and stricture formation, which was gently passed with the endoscope (Fig. 2B). She was discharged from hospital and a month later the study was repeated with no residual lesion.

EVL complications are at a rate lower than 15% and include: ulcers, transient dysphagia, chest pain, bleeding, stricture formation and infections. The first case of aphagia after an EVL was reported by Saltzman and Arora in 1993. The aphagia was not caused by a unique band, but by the newly banded varices that completely obstructed the esophageal lumen. The obstruction was resolved by pushing away the bands with an endoscope twenty-four hours after the procedure.10 So far, we have found four cases published like ours.6–9 Saftoiu et al. reported the first case. Forty-eight hours after the ligation, they observed the obstruction and managed to unblock the esophagus pushing softly. In a similar case, Verma et al. repeated the endoscopy without trying to dislodge the obstruction. They adopted a wait-and-see approach and a week later the patient could eat food. Nikoloff et al. do not suggest performing the endoscopy owing to a bleeding risk but they recommend contrast swallow studies and watchful waiting until their patient could swallow liquids. In their case, the patient was able to swallow liquids seven days after the ligation. Chahal et al. performed an endoscopy using forceps to unblock the obstruction. However, they had to stop the procedure due to a small amount of bleeding. In our case, we decided to perform an endoscopy, tried to push and carefully remove the band with forceps. As the endoscope could not pass, we adopted expectant behavior. Forty eight hours later the patient was able to swallow liquids (four days after the ligation). Factors that could be present in a situation like this are: technical defect, edema, the size of the band and a ball-valve effect (when the varix is banded, near a previous banding stricture).8 In all the cases that a watchful waiting approach was adopted, the medical evolution was good and it was probably the best way to proceed.

FundingThe authors have not received any funding or benefits from industry or elsewhere to conduct this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have not declared any conflicts of interest.