Clinical practice guidelines for the management of constipation in adults aim to generate recommendations on the optimal approach to chronic constipation in the primary care and specialized outpatient setting. Their main objective is to provide healthcare professionals who care for patients with chronic constipation with a tool that allows them to make the best decisions about the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of this condition. They are intended for family physicians, primary care and specialist nurses, gastroenterologists and other health professionals involved in the treatment of these patients, as well as patients themselves. The guidelines have been developed in response to the high prevalence of chronic constipation, its impact on patient quality of life and recent advances in pharmacological management. The Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) system has been used to classify the scientific evidence and strengthen the recommendations.

La guía de práctica clínica sobre el manejo del paciente con estreñimiento en los pacientes adultos se fundamenta en una serie recomendaciones y estrategias con el objetivo de proporcionar a los profesionales sanitarios encargados de la asistencia a pacientes con estreñimiento crónico una herramienta que les permita tomar las mejores decisiones sobre la prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento del estreñimiento. Esta guía de práctica clínica persigue una atención eficiente del estreñimiento a partir de un trabajo coordinado y multidisciplinar con la participación de la atención primaria y especializada. La guía va dirigida a los médicos de familia, a los profesionales de enfermería de atención primaria y especializada, a los gastroenterólogos, a otros especialistas que atienden a pacientes con estreñimiento y a las personas afectadas con esta problemática. La elaboración de esta guía se justifica fundamentalmente por la elevada frecuencia del estreñimiento crónico, el impacto que este tiene en la calidad de vida de los pacientes y por los avances recientes en el manejo farmacológico del estreñimiento. Para clasificar la evidencia científica y la fuerza de las recomendaciones se ha utilizado el Grading of RecommendationsAssessment, Development and EvaluationWorking Group (sistema GRADE).

Constipation is a symptom suffered by a large number of people and which is brought about by multifactorial causes. Many people have experienced constipation at some point in their life, although it usually occurs for a limited period of time and is not a serious problem. Long-term constipation affects women and older adults more frequently. It is a disorder that has a negative effect on people's well-being and quality of life. It is a common reason for medical consultation in primary care and is treated by self-medication by a high proportion of the affected population. Knowing the causes, preventing, diagnosing and treating constipation will benefit many of those affected.

In order for clinical decisions to be appropriate, efficient and safe, professionals need to update their knowledge constantly. This clinical practice guideline (CPG) on the management of chronic constipation in adult patients sets out the efficient treatment of this disorder using a coordinated and multidisciplinary approach with the participation of primary and specialised care.

MethodologyProfessional representatives of the scientific societies involved and methodologists participated in the preparation of this CPG. All the essential criteria referred to in the Appraisal of Guidelines, Research and Evaluation for Europe (AGREE) (http://www.agreecollaboration.org/), a tool designed to help producers and users of CPG and considered the standard for their preparation, have been taken into account in the preparation of this guideline.

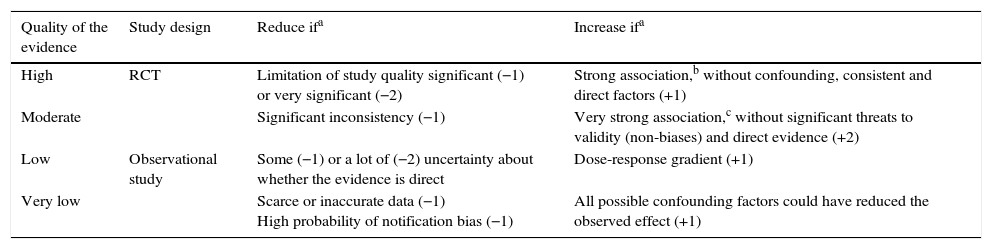

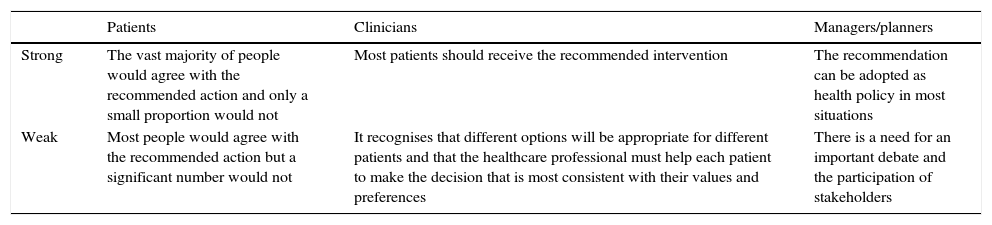

For the classification of the scientific evidence and the strength of the recommendations, the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE system) (http://www.gradeworkinggroup.org/)1–3 (Tables 1 and 2) was used.

Assessment of the quality of evidence for each variable. GRADE System.

| Quality of the evidence | Study design | Reduce ifa | Increase ifa |

|---|---|---|---|

| High | RCT | Limitation of study quality significant (−1) or very significant (−2) | Strong association,b without confounding, consistent and direct factors (+1) |

| Moderate | Significant inconsistency (−1) | Very strong association,c without significant threats to validity (non-biases) and direct evidence (+2) | |

| Low | Observational study | Some (−1) or a lot of (−2) uncertainty about whether the evidence is direct | Dose-response gradient (+1) |

| Very low | Scarce or inaccurate data (−1) High probability of notification bias (−1) | All possible confounding factors could have reduced the observed effect (+1) |

RCT, randomised clinical trial.

Strength of recommendations. GRADE system.

| Patients | Clinicians | Managers/planners | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strong | The vast majority of people would agree with the recommended action and only a small proportion would not | Most patients should receive the recommended intervention | The recommendation can be adopted as health policy in most situations |

| Weak | Most people would agree with the recommended action but a significant number would not | It recognises that different options will be appropriate for different patients and that the healthcare professional must help each patient to make the decision that is most consistent with their values and preferences | There is a need for an important debate and the participation of stakeholders |

Once a complete draft of the guide had been prepared, the external reviewers, who were representatives of the various related specialties, provided their comments and suggestions.

DefinitionConstipation is characterised by difficult or infrequent bowel movements, often accompanied by excessive exertion during defecation or a feeling of incomplete evacuation.4 In most cases it does not have an underlying organic cause and is considered chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC), also known as chronic functional constipation. In fact, CIC shares several symptoms with irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), although in IBS-C, abdominal pain/discomfort must be present to make the diagnosis.5 Even so, there are authors who consider CIC and IBS-C as 2 different entities and others that include them as subsections of the same spectrum.4–6

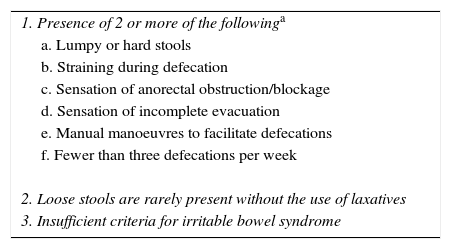

According to the Rome III criteria, CIC is defined as the presence during the last 3 months of 2 or more of the conditions reflected in Table 3. Symptoms must have started at least 6 months before diagnosis, there should only be diarrhoea after laxative intake and IBS criteria should not be met.5

Functional chronic constipation. Rome III criteria.

| 1. Presence of 2 or more of the followinga |

| a. Lumpy or hard stools |

| b. Straining during defecation |

| c. Sensation of anorectal obstruction/blockage |

| d. Sensation of incomplete evacuation |

| e. Manual manoeuvres to facilitate defecations |

| f. Fewer than three defecations per week |

| 2. Loose stools are rarely present without the use of laxatives |

| 3. Insufficient criteria for irritable bowel syndrome |

a–e in ≥25% of defecations+for the last 3 months, with symptom onset at least 6 months prior to diagnosis.

Source: Longstreth et al.5.

CIC is very common in the general population around the world, with a mean prevalence, as estimated in 2 systematic reviews, of between 14% (95% CI: 12–17%)4 and 16% (95% CI: 0.7–79%).7 The studies conducted in Spain reveal a prevalence of 14–30%.8–10 CIC is more prevalent in women4,7,10–12; its prevalence increases progressively after 60 years of age.7 CIC is normally long-term. In a recent study, it was observed that 68% of the patients were constipated for 10 years or more.13

CIC is a major problem not only because of its prevalence, but also because of its personal, social, employment and economic impact. Its physical and mental impact affects quality of life and personal well-being.11,12,14 The cost of constipation healthcare and treatment are very significant. Results of a study conducted in our setting indicate that constipation consumes a significant amount of resources, both in relation to the use of laxatives and medical visits.15

Risk factorsIn addition to age and the female gender, a number of aetiological factors have been studied for CIC, the assessment of which comes mostly from uncontrolled studies and short-term interventions.

It is believed that a low-fibre diet contributes to constipation and many doctors recommend increased fibre intake along with other lifestyle changes such as improved hydration and exercise. However, the scientific evidence is contradictory.7

Some observational studies have shown that fibre intake is associated with an improvement in constipation16 while others have not.17,18 Some studies have even found that reducing fibre intake improves constipation and the associated symptoms.18

The results of an observational study (10,914 people) show that low fluid intake is a predictor of constipation for both women (OR=1.3; 95% CI: 1.0–1.6) and for men (OR=2.4; 95% CI: 1.5–3.9).17

Prolonged physical inactivity slows digestive activity in healthy volunteers.19 Some studies show that moderate physical activity is associated with a fall in the prevalence of constipation,16 while others, conversely, find otherwise.17,20

Other risk factors associated with CIC are low educational and socio-economic levels,7,21 being overweight and obesity.7 A family history of constipation, anxiety, depression and stressful life events also favour constipation.7

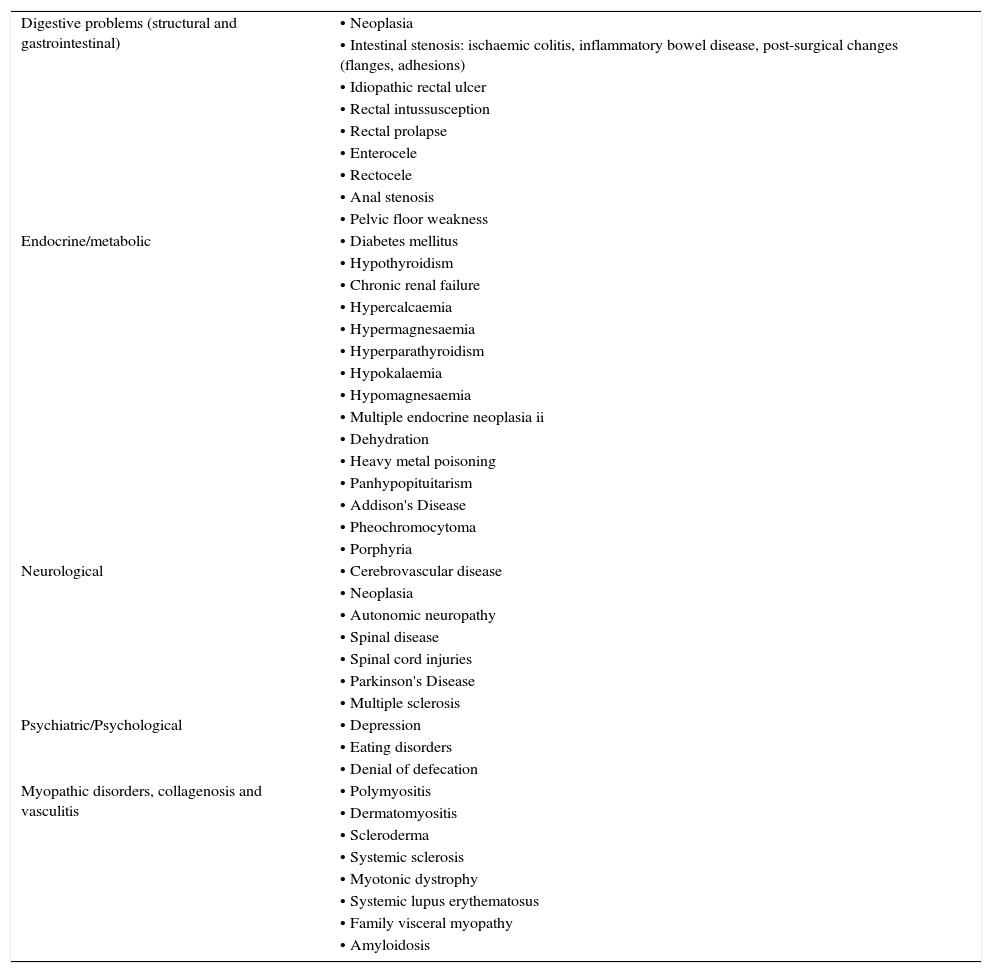

Causes of constipationConstipation is a symptom and not a disease in itself and can be a consequence of multiple causes. Secondary chronic constipation may be associated with a wide range of diseases22 (Table 4) and/or drugs22 (Table 5). Once secondary causes are excluded, CIC is considered, which is a consequence of primary functional impairment of the colon and anus-rectum.

List of diseases associated with chronic constipation.

| Digestive problems (structural and gastrointestinal) | • Neoplasia |

| • Intestinal stenosis: ischaemic colitis, inflammatory bowel disease, post-surgical changes (flanges, adhesions) | |

| • Idiopathic rectal ulcer | |

| • Rectal intussusception | |

| • Rectal prolapse | |

| • Enterocele | |

| • Rectocele | |

| • Anal stenosis | |

| • Pelvic floor weakness | |

| Endocrine/metabolic | • Diabetes mellitus |

| • Hypothyroidism | |

| • Chronic renal failure | |

| • Hypercalcaemia | |

| • Hypermagnesaemia | |

| • Hyperparathyroidism | |

| • Hypokalaemia | |

| • Hypomagnesaemia | |

| • Multiple endocrine neoplasia ii | |

| • Dehydration | |

| • Heavy metal poisoning | |

| • Panhypopituitarism | |

| • Addison's Disease | |

| • Pheochromocytoma | |

| • Porphyria | |

| Neurological | • Cerebrovascular disease |

| • Neoplasia | |

| • Autonomic neuropathy | |

| • Spinal disease | |

| • Spinal cord injuries | |

| • Parkinson's Disease | |

| • Multiple sclerosis | |

| Psychiatric/Psychological | • Depression |

| • Eating disorders | |

| • Denial of defecation | |

| Myopathic disorders, collagenosis and vasculitis | • Polymyositis |

| • Dermatomyositis | |

| • Scleroderma | |

| • Systemic sclerosis | |

| • Myotonic dystrophy | |

| • Systemic lupus erythematosus | |

| • Family visceral myopathy | |

| • Amyloidosis |

Adapted from Lindberg et al.22.

List of drugs associated with chronic constipation (abridged list).

| Central nervous system | • Antiepileptics (carbamazepine, phenytoin, clonazepam, amantadine, etc.) |

| • Antiparkinson drugs (bromocriptine, levodopa, biperiden, etc.) | |

| • Anxiolytics and hypnotics (benzodiazepines, etc.) | |

| • Antidepressants (tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, etc.) | |

| • Antipsychotics and neuroleptics (butyrophenones, phenothiazines, barbiturates, etc.) | |

| Digestive system | • Antacids (containing aluminium, calcium) |

| • Proton-pump inhibitors | |

| • Anticholinergic antispasmodics (natural alkaloids and synthetic and semisynthetic derivatives with a tertiary and quaternary amine structure such as atropine, scopolamine, butylscopolamine, methylscopolamine, trimebutine, pinaverium, etc.) or musculotropic drugs (mebeverine, papaverine, etc.) | |

| • Antiemetics (chlorpromazine, etc.) | |

| • Supplements (salts of calcium, bismuth, iron, etc.) | |

| • Antidiarrhoeal agents | |

| Circulatory system | • Antihypertensives (beta-blockers, calcium-antagonists, clonidine, hydralazine, ganglion blockers, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, methyldopa, etc.) |

| • Antiarrhythmics (quinidine and derivatives) | |

| • Diuretics (furosemide) | |

| • Hypolipidemics (cholestyramine, colestipol, statins, etc.) | |

| Other | • Analgesics (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, opiates and derivatives, etc.) |

| • Antihistamines against H1 receptors | |

| • Antitussives (codeine, dextromethorphan, etc.) | |

| • Metallic ions (aluminium, barium sulphate, bismuth, calcium, iron, etc.) | |

| • Cytostatic agents |

Adapted from Lindberg et al.22.

Constipation can essentially be caused by 2 mechanisms23: (1) slow transit through the different segments of the colon and (2) defecation disorders. In some patients, both mechanisms may be present, although there is a large group of patients in whom none of these abnormalities is seen. In these cases, constipation is associated with alterations in rectal sensitivity, either a decrease in sensitivity, or an increase in sensitivity and forming part of IBS-C.24

- 1)

Slow colonic transit (colonic inertia). This may be caused by metabolic or endocrine disorders, systemic diseases or by certain drugs. However, it may also be primary, possibly associated with neuropathic or myopathic disorders of the colon wall, as suggested by the decrease in the number of interstitial cells of Cajal,25 or the decreased response to cholinergic stimulation observed in some of these patients.26 As the intestinal contents remain longer in the colon, the absorption of water and electrolytes increases, resulting in a decrease in volume and a hardening of the stool. As a result, the volume of stools, the feeling of the need to defecate and the ease of expelling stools at defecation will all be reduced. In some cases, stagnation of the intestinal contents can lead to the formation of faecalomas. The slowing down of colonic transit may also be due to defecation disorders as evidenced by the fact that the success of treatment with anorectal biofeedback normalises colonic transit.27

- 2)

Defecation disorder. Difficulty in defecation may be due to neurological abnormalities such as Hirschsprung's disease or spinal cord injuries, or to anatomical alterations such as rectoceles, enterocele, intussusception, etc. However, in most cases there is no evidence of structural alterations or neurological lesions justifying the difficulty of expulsion, which is considered to be produced by a functional defecation disorder.28 The functional defecation disorder may be due to one or more of the following conditions:

- a)

Reduction of rectal sensitivity. The arrival of the faeces in the rectum stimulates sensory receptors that send impulses to the cerebral cortex through afferent nerve pathways. These inform the brain of the presence of the faeces in the rectum and will produce the desire to defecate. An alteration in the sensitivity of the rectum, sometimes associated with a decrease in rectal tone, may result in primary constipation.23

- b)

Dyssynergic defecation or poor coordination during defecation. At the time of defecation, there is a coordinated increase in abdominal pressure, which is achieved by contracting the muscles of the abdominal wall and the diaphragm, and a relaxation of the anal sphincter, which is associated with a drop of the perineum and rectification of the angle of the rectum with the anal canal. Three types of coordination abnormality or dyssynergic defecation have been described29: type (I) Increase of adequate rectal pressure with paradoxical contraction of the anal sphincter during the defecation manoeuvre; type (II) Increased weak or insufficient rectal pressure, and type (III) Absence of sphincter relaxation with increased rectal pressure. Types I and III will produce a functional obstruction to defecation, whereas type II results in impaired propulsion. The propulsion deficiency may be associated with an insufficient abdominal press or impaired colonic contractile activity. The practical importance of identifying the mechanisms that produce defecation disorders is so that they can be corrected by anorectal biofeedback, which has been shown to be a very effective treatment of defecation disorders.30,31

- a)

Constipation with normal transit is defined as constipation even though the transport time of the faeces through the colon is normal.

SymptomsMedical historyIn the vast majority of patients, the diagnosis of CIC is based on the description of the symptoms and/or signs recorded in the medical history and the findings of the physical examination. Three aspects must be taken into account: (1) compliance with the diagnostic criteria for chronic constipation, (2) determination of the causes of constipation and (3) detection of signs of alarm. A detailed assessment of signs and/or symptoms may help differentiate between constipation due to slow colonic transit and a functional defecation disorder.

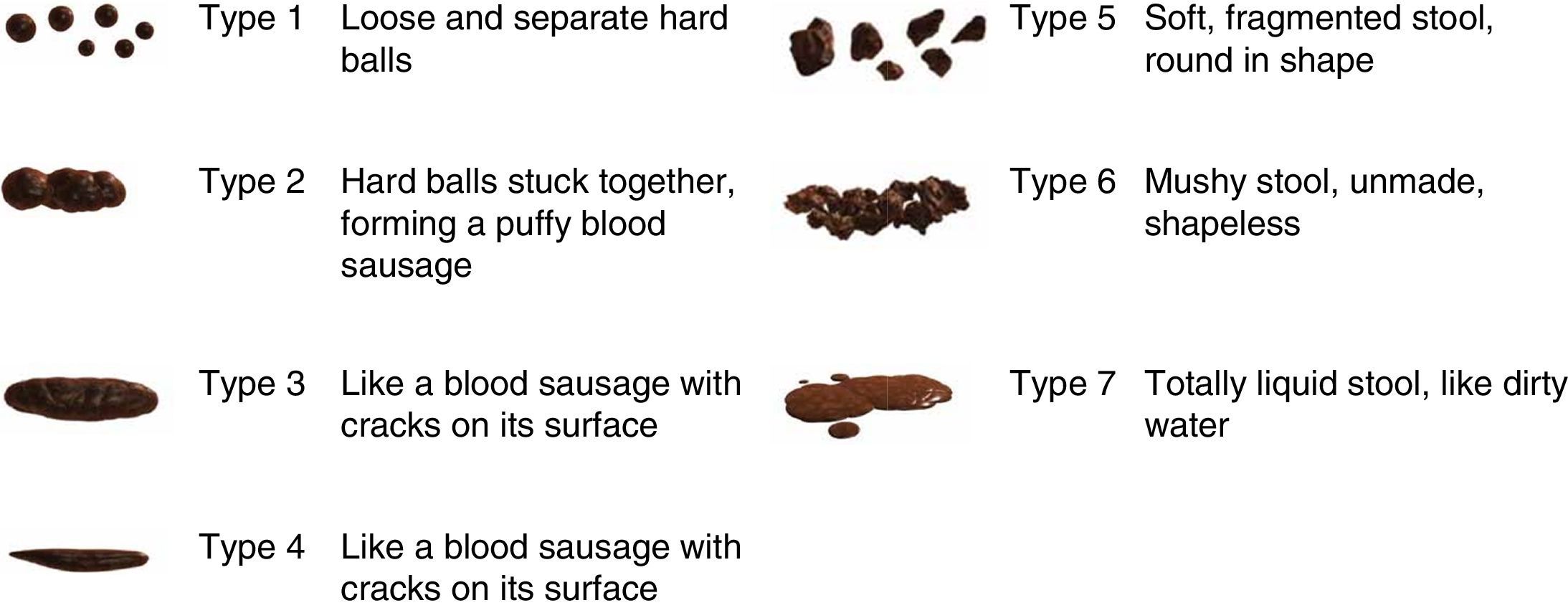

In order to evaluate compliance with the Rome III criteria5 (Table 3), the patient should be asked about: the onset and duration of symptoms; the shape and consistency of the stool: it is recommended to use the Bristol scale32 (Fig. 1); the difficulty in evacuation: the patient should be asked about straining during defecation, the feeling of incomplete evacuation, the sensation of blockage or anal obstruction and/or the need to use fingering manoeuvres to expel the faeces; bowel movement frequency; changes in bowel habits (alternating diarrhoea with constipation) and abdominal pain; other relevant aspects such as the presence of anal pain during defecation, defecation urgency and/or faecal incontinence.

Bristol Scale for faeces assessment. Visual table with illustrations.

Source: Lewis and Heaton.32

To determine the possible predisposing causes and factors, the patient must be asked about their dietary and lifestyle habits, substance abuse, medication (including laxatives), bowel habits, pathological history and history of diseases (obstetric events, etc.) as well as their profession.

In the event of signs of alarm, additional tests should be performed to rule out an organic cause of the constipation33–35: Signs of alarm include a sudden change in persistent usual bowel rhythm (>6 weeks) in patients over 50 years of age, rectal bleeding or bloody stool, iron deficiency anaemia, weight loss, significant abdominal pain, family or personal history of colorectal cancer (CRC) or inflammatory bowel disease and palpable mass.

Physical examinationIn the event of constipation, a complete physical examination should be performed, including abdominal examination, visual inspection of the perianal and rectal region and a digital rectal examination. A physical examination is performed to look for signs of an organic disease and to evaluate the presence of masses, prolapse, haemorrhoids, fissures, rectocele, faeces in rectum, etc.

The digital rectal examination evaluates the tone of the anal sphincter, both at rest and during a bowel movement, and the presence of faeces in the rectal ampulla. Recent studies show that digital rectal examination has a high probability of detecting pelvic floor dyssynergia.36,37

Comorbidities and complications of constipationThe association between constipation and related gastrointestinal and extraintestinal comorbidities is not well documented.38 The available evidence is inferred from association studies and knowledge of the pathogenesis of constipation. However, in many of these studies there are several confounding factors and there is an overlap between chronic constipation and other functional gastrointestinal disorders.38,39

A review of studies published between 1980 and 2007 evaluated the association between constipation and various related comorbidities, especially the most common anorectal, colon and urological disorders.38,40–42 The most prevalent associations are: haemorrhoids, anal fissures, rectal prolapse and stercoral ulceration, faecal impaction, faecal incontinence, megacolon, volvulus, diverticular disease, urinary tract infections, enuresis and urinary incontinence. Many of these conditions have also been identified in a more recent review that includes studies published between January 2011 and March 2012.39 This review also evaluates other extragastrointestinal comorbidities: overweight, obesity, depression, diabetes and urinary disorders.39

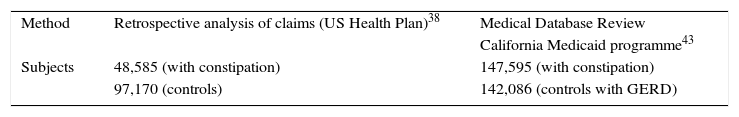

The broader studies on the prevalence and association of the various concurrent conditions with chronic constipation come from retrospective cohort studies using the California Medicaid database43 and the US Health Plan database44 (Table 6). The analysis of the Medicaid database, taking into account the possible detection bias, partly modifies the previously published results.38

Gastrointestinal comorbidities and complications of constipation.

| Method | Retrospective analysis of claims (US Health Plan)38 | Medical Database Review |

| California Medicaid programme43 | ||

| Subjects | 48,585 (with constipation) | 147,595 (with constipation) |

| 97,170 (controls) | 142,086 (controls with GERD) |

| Complication/Comorbidity | OR (p-value) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Anal fissure | 5.04 | 2.47 (2.12–2.84) |

| Anal fistula | NE | 1.72 (1.37–2.15) |

| Haemorrhage (rectum/anus) | NE | 1.36 (1.30–1.43) |

| Ulcer (rectum/anus) | 4.76 | 2.11 (1.66–2.69) |

| Diverticular disease | 2.1 | 1.04 (1–1.08) |

| Crohn's Disease | 0.3 | 0.96 (0.85–1.07) |

| Faecal impaction | 6.58 | 3.20 (2.83–3.62) |

| Faecal incontinence | NE | 1.16 (0.99–1.35) |

| Haemorrhoids | 4.19 | 1.24 (1.2–1.3) |

| Hirschsprung's disease | NE | 4.42 (2.46–7.92) |

| Irritable bowel syndrome | 4.2 | 1.12 (1.07–1.18) |

| Colorectal cancer | 4.6 | 1.16 (1.05–1.30) |

| Rectal prolapse | NE | 1.63 (1.9–2.9) |

| Bowel obstruction | 4.10 | – |

| Ulcerative colitis | 0.5 | 0.86 (1.27–2.10) |

| Intestinal volvulus | 10.34 | 1.36 (1.07–1.72) |

Several retrospective cohort studies38,43 (Table 6) and prospective studies have described a significant association between chronic constipation and haemorrhoids. It is suggested that the prolonged intra-abdominal pressure exerted on the venous plexuses and anorectal arteriovenous anastomosis may lead to local circulatory disorders such as internal and/or external haemorrhoids.38

Anal fissureThere are different retrospective analyses that support the relationship between chronic constipation and the appearance of anal fissures38,43 (Table 6). It has been suggested that mucosal injury is caused by a traumatic action due to the passage of hard faeces through the rectal canal during usual defecation strain, local ischaemic involvement and some anal sphincter dysfunction.38

ProlapseRectal prolapse is a condition characterised by the protrusion of the rectum through the anus. Performing frequent and sustained Valsalva manoeuvres can be a contributing factor. The slowing of colonic transit and motility disorders have been related to the appearance or exacerbation of a rectal prolapse. A retrospective cohort study43 described a significant association between chronic constipation and rectal prolapse (Table 6). A systematic review (12 case series studies) shows that constipation decreases after prolapse surgery.45

UlcersSeveral retrospective cohort studies38,43 have described a significant association between chronic constipation and ulcers (Table 6). Rectal ulcers are an uncommon but probably underestimated complication since stercoral perforations are often identified as spontaneous, idiopathic or secondary. The perforation may go unnoticed clinically as minor episodes of rectal bleeding, or become extremely complicated in case of infection or even bacteraemia with stercoral peritonitis with a very severe prognosis.38 It is suggested that sustained pressure of the wall of the colon and rectum by a direct effect of mass due to the constant presence of faecal matter can lead to a chronic ischaemic injury accompanied by wall necrosis, causing stercoral colonic ulcers.

Faecal impaction or faecalomaAlthough studies designed to assess the aetiology and risk factors of faecal impaction in chronic constipation are limited, data from retrospective studies are consistent in suggesting a higher risk in patients with a previous diagnosis of chronic constipation. In fact, faecal impaction is one of the most frequent complications of chronic constipation.38,43 This condition is caused by accumulation of faeces in the rectal ampulla (although it may occur in both the rectal and colonic tracts), where a period of stasis, some loss of colonic function and anorectal sensitivity, accompanied by alterations in hydration, can lead to the onset of faecalomas that result in impaction and obstruction of the intestinal lumen.38

Faecal incontinenceSeveral studies have shown a positive association between chronic constipation and faecal incontinence,38,43,44,46,47 most commonly in elderly and institutionalised patients. Clinically speaking, faecal incontinence manifests as the paradoxical leakage of loose or semi-loose faeces around the obstructed stool in the rectal ampulla (overflow faecal incontinence).

Colon complicationsDiverticular diseaseThere are several retrospective studies supporting a discrete association between chronic constipation and diverticular disease38,43,44 (Table 6). However, the role of chronic constipation remains uncertain and probably represents the coexistence of two very common entities38. It is believed that prolonged colonic transit time and low volume of faeces are associated with an increase in intraluminal pressure, which may lead to pulsion diverticula forming at the weakest points of the colon wall.

MegacolonChronic megacolon may be secondary to an advanced stage of refractory chronic constipation or present as a primary colonic disease. Most adults with an idiopathic megacolon have a long history of chronic constipation.38 It has been observed that the presence of megacolon in the event of previous chronic constipation was 5 times more frequent than in its absence.38

VolvulusSigmoid volvulus is a common cause of bowel obstruction. It has multiple causes and is more common in patients with a longstanding megacolon. Retrospective studies have indicated that the presence of a volvulus is significantly more frequent in the context of chronic constipation.38

Colorectal cancerA systematic review of observational studies (28 studies) concludes that there is no association between constipation and CRC.48 The results of the 8 cross-sectional studies included show that the presence of constipation as the main indication for colonoscopy was associated with a lower prevalence of CRC (OR=0.56; 95% CI: 0.36–0.89). In the 3 cohort studies, a non-significant decrease in CRC was observed in patients with constipation (OR=0.80; 95% CI: 0.61–1.04). In the 17 case–control studies, on the other hand, the prevalence of constipation in CRC was significantly higher than in controls without CRC (OR=1.68; 95% CI: 1.29–2.18), but with significant heterogeneity and possible publication bias.

Extracolonic complicationsUrological disordersRetrospective and prospective studies in both adults and children suggest that chronic constipation may have an aetiological relationship to the presence of urinary tract infections, enuresis and urinary incontinence.38,49–52

Other complicationsOther indirect complications could be caused by the therapeutic approach itself, such as the side effects of local therapies (rectal mucosal injury, even at risk of perforation especially in debilitated patients), syncopal episodes during manual removal of faecalomas or adverse effects of laxative medications.

ConclusionsChronic constipation is a very common disorder that tends to affect women and the elderly and which can be triggered by multiple causes. Functional constipation, although it may be considered as a common symptom, is associated with multiple complications, both in the rectum or colon, as well as extraintestinal complications. A thorough medical history and physical examination will be key to determining the likely cause of constipation in an individual patient and will be used as a guide for the correct management of the condition.

FundingSources of funding: this clinical practice guideline has received external funding from Laboratorios Shire. The sponsors have not influenced any stage of its development.

Conflicts of interestJordi Serra is a consultant from Norgine and works with Almirall, Allergan, Cassen-Recordati and Zespri; Sílvia Delgado has been a consultant to Shire (Resolor) and Almirall (Constella); Enrique Rey: Conferences and research funding from Almirall and Norgine Iberia; Fermín Mearin, Advisor for Laboratorios Almirall; Juanjo Mascort, Juan Ferrandiz and Mercè Marzo have no conflict of interest to declare.

The following people have acted as external reviewers:

Carmen Vela Vallespín. General practitioner, Riu Nord i Sud Primary Care Centre (CAP) Catalan Health Institute Santa Coloma, Barcelona.

Iván Villar Balboa. General practitioner, Florida Sud Primary Care Centre (CAP) Catalan Health Institute, L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona.

Mercè Barenys de Lacha. Gastroenterologist, Hospital de Viladecans. Professor of Gastroenterology, University of Barcelona. IDIBELL Scientific Committee.

Francisco Javier Amador Romero. General practitioner, Los Ángeles Health Centre, Madrid.

Miguel Mínguez Pérez. Gastroenterologist, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valencia.

This CPG has the support of the following organisations:

- -

Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology].

- -

Sociedad Española de Medicina Familiar y Comunitaria (semFYC) [Spanish Society of Family and Community Medicine].

Please cite this article as: Serra J, Mascort-Roca J, Marzo-Castillejo M, Delgado Aros S, Ferrándiz Santos J, Rey Diaz Rubio E, et al. Guía de práctica clínica sobre el manejo del estreñimiento crónico en el paciente adulto. Parte 1: Definición, etiología y manifestaciones clínicas. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:132–141.