The small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) has revolutionised the study of small bowel (SB) diseases. The objective of this study is to determine the indications, findings and diagnostic yield of SBCE in a national registry.

Patients and methodsAn observational, analytical cross-sectional study was carried out, analysing the SBCE records at seven centres in the country, where different variables were collected.

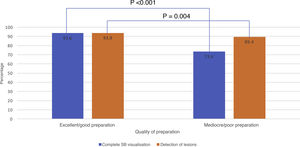

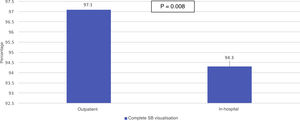

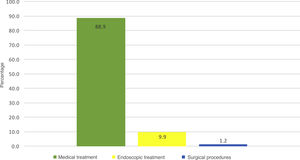

Results1,883 SBCEs were evaluated. The average age was 55.4 years (5.6–94.2). The most frequent indications were suspicion of small bowel bleeding (SBB) (64.4%), study of Crohn’s disease (15.2%) and chronic diarrhoea (11.2%). 54.3% were prepared with laxatives. The most frequent lesions found were erosions/ulcers (31.6%), angioectasias (25.7%) and parasitosis (2.7%). The diagnostic yield (P1+P2, Saurin classification) of SBCE in SBB was 60.6%, being higher in overt SBB (66.0%) compared to occult SBB (56.0%) (P=0.003). The studies with better preparation showed higher detection of lesions (93.8% vs. 89.4%) (OR=1.8, CI: 95%: 1.2–2.6; P=0.004). The SBCE complication rate was 3.1%, with complete SB visualisation at 96.6% and SB retention rate of 0.7%. 81.5% of SBCEs were performed on an outpatient basis, and presented a greater complete SB visualisation than hospital ones (97.1% vs. 94.3%) (OR=2.1, CI: 95%, 1.2–3.5; P=0.008).

ConclusionsThe indications, findings and diagnostic performance of SBCEs in Colombia are similar to those reported in the literature, with a high percentage of complete studies and a low rate of complications.

La video cápsula endoscópica (VCE) ha revolucionado el estudio de las patologías de intestino delgado (ID). El objetivo de este estudio es determinar las indicaciones, hallazgos y rendimiento diagnóstico de la VCE en un registro nacional.

Pacientes y métodosSe realizó un estudio observacional, de corte transversal analítico, analizando los registros de VCE en siete centros del país, se recolectaron diferentes variables.

ResultadosSe evaluaron 1.883 estudios de VCE. La edad promedio fue 55.4 años (5.6–94.2). Las indicaciones más frecuentes fueron sospecha de sangrado de intestino delgado (SID) (64.4%), estudio enfermedad de Crohn (15.2%) y diarrea crónica (11.2%). 54.3% de VCE se prepararon con laxantes. Las lesiones más frecuentes fueron erosiones/úlceras (31.6%), angiectasias (25.7%) y parasitosis (2.7%). El rendimiento diagnóstico (P1+P2, clasificación de Saurin) de VCE en SID fue 60.6%, siendo mayor en SID evidente (66.0%) comparado con SID oculto (56.0%) (P=0.003). Los estudios con mejor preparación presentaban mayor detección de lesiones (93.8% vs 89.4%) (OR=1.8, IC: 95%: 1.2–2.6; P=0.004). La tasa de complicación de VCE fue 3.1%, con visualización completa del ID en 96.6% y tasa de retención en ID de 0.7%. 81.5% de VCE se realizaron en forma ambulatoria, y presentaron mayor visualización completa de ID que las hospitalarias (97.1% vs 94.3%) (OR=2.1, IC: 95%, 1.2–3.5; P=0.008).

ConclusionesLas indicaciones, hallazgos y rendimiento diagnóstico de VCE en Colombia son similares a los reportados en la literatura universal, con alto porcentaje de estudios completos y baja tasa de complicaciones.

Since its launch as a diagnostic tool in 2000, video capsule endoscopy (VCE) has revolutionised the study of small bowel (SB) disease all over the world.1 VCE enables the SB to be visualised in patients with a broad spectrum of disorders, from obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) to Crohn’s disease (CD), hereditary polyposis syndromes and coeliac disease.2,3

The term OGIB, defined as gastrointestinal bleeding in subjects with normal upper GI endoscopy and colonoscopy, has recently been changed to potential small bowel bleeding (SBB). This type of bleeding is classified as: visible or overt, due to the presence of bleeding from the mouth, manifesting as haematemesis, or rectum, manifesting as haematochezia or melaena; or occult, defined as persistence of positive faecal occult blood and/or iron deficiency anaemia (IDA), with no evidence of visible bleeding. The term OGIB is currently reserved only for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding of unknown origin after a complete evaluation of the gastrointestinal tract with upper endoscopy, total colonoscopy and SB studies.4,5

In patients with suspected SBB, VCE has become a very important diagnostic method in recent years. One systematic review found that OGIB was the most common indication (66.0%), with a lesion detection rate of 60.5%.6 Another systematic review, which included only patients with IDA with previous normal upper endoscopy and colonoscopy, found a diagnostic yield of 47%.7 In CD, VCE had a better diagnostic performance than ileoscopy, intestinal transit and CT enterography, but no significant difference was found compared to magnetic resonance enterography.8 VCE is indicated in patients with coeliac disease who have unexplained symptoms despite adequate treatment, due to its high sensitivity and specificity in the study of this disease.2,3,9

Despite being a safe procedure, VCE is not without complications. Complications such as aspiration and capsule retention in the stomach or SB have been reported, requiring medical, endoscopic or surgical management.10

Various isolated studies with VCE at prominent centres here in Colombia have been published.11–14 However, we believe a national study is necessary that includes the vast majority of centres with experience in this endoscopic procedure in our country. The aim of this study was to determine the indications for VCE, and the associated findings, diagnostic performance, complications and management approach after completion, among patients having this procedure in Colombia.

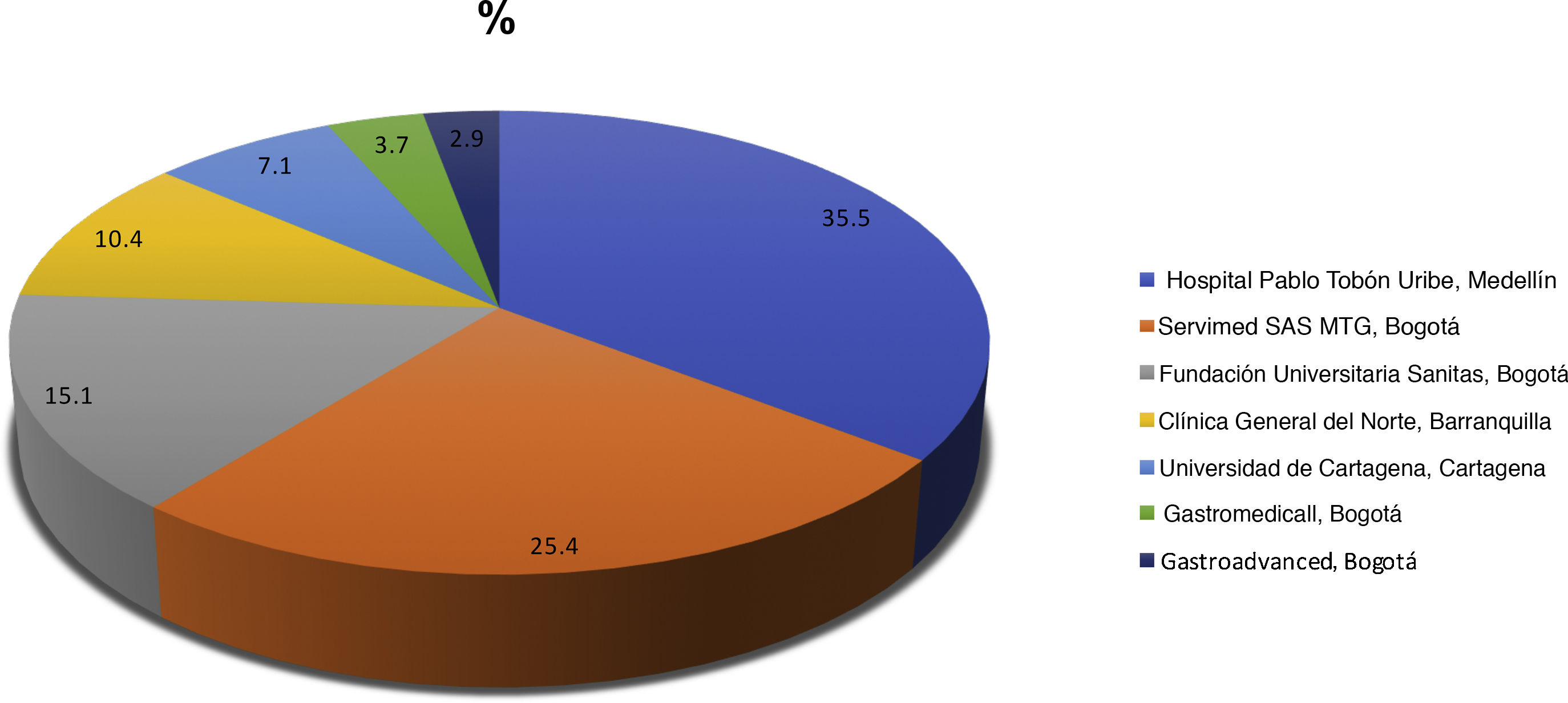

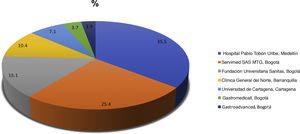

Patients and methodsType of studyThis was a multicentre, observational, analytical cross-sectional study with a retrospective approach. A call was put out to all hospital and outpatient centres that perform VCE here in Colombia, and we were able to include the most prominent centres with the most experience in VCE in the country. All VCEs performed in the different centres from January 2006 to October 2019 were included. The seven participating centres, with their respective city of origin, and the number of VCE studies that contributed to the national registry (in brackets), were as follows: Hospital Pablo Tobón Uribe, Medellín (668), Servimed SAS MTG, Bogotá (479), Fundación Universitaria Sanitas, Bogotá (284), Clínica General del Norte, Barranquilla (195), Universidad de Cartagena, Cartagena (134), Gastromedical, Bogotá (69) and Gastroadvanced, Bogotá (54). Data from all patients with a VCE study due to suspected SB disease at the above hospital and outpatient centres were included retrospectively.

Data collectionA database was constructed using Excel which was distributed to each participating centre, and the following variables were collected from each VCE study for analysis: (1) patient identification; (2) institution; (3) study date; (4) date of birth; (5) patient gender; (6) indication for the procedure; (7) origin of the patient (outpatient or hospital); (8) preparation prior to the procedure; (9) model of VCE used; (10) mode of advancing to the duodenum; (11) qualitative quality of the preparation; (12) type of lesions found; (13) location of lesions; (14) clinical relevance of the lesion; (15) complete visualisation of the SB; (16) presence of complications; (17) management of complications; and (18) medical approach post-VCE.

All the patients at the different centres were prescribed a liquid diet the day before and were prepared with polyethylene glycol at a dose of 2L the night before the study. Patients who did not receive preparation were advised to adhere to a clear liquid diet the day before the study. To measure the quality of the SB preparation, a previously validated qualitative scale was used which is divided into four categories - excellent, good, fair and poor - depending on the percentage of visualisation of the mucosa, its brightness, and the presence of debris and bubbles in the intestinal lumen.15 The study was considered a complete SB VCE when the capsule reached the colon during the recording, and capsule retention in SB was defined as when the capsule still remained in the SB 15 days after the study.16 The relevance of the lesions was documented according to their potential to cause bleeding, according to Saurin’s classification: P0 - lesions without bleeding potential such as phlebectasia, bloodless diverticula, or subepithelial lesions without erosion of the mucosa; P1 - lesions with uncertain bleeding potential, within which are “red spots”, small or isolated erosions; and lastly, P2 - lesions with high bleeding potential, such as angioectasia, ulcers, tumours or varicose veins. In order to determine the diagnostic yield, P1 and P2 lesions have to be taken into account.17

Statistical analysisA univariate analysis was initially performed where absolute and relative frequencies were used for qualitative variables, and mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (P25−75) were used for quantitative variables, after verification of the assumption of normality. The quantitative variables were dichotomised and it was decided to make a comparison of proportions and so the Chi-square test of independence or Fischer’s test was used and the odds ratio (OR) was estimated with its respective 95% confidence interval. In all cases, a p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. We used the freely available JAMOVI statistical package and Epidat version 3.1.

Ethical considerationsThis research involved no risk, as we only used the information sent by the researchers from their clinical practice, where the confidentiality and privacy of the information collected was guaranteed. The project researchers adhered to the international principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (version 2013, Fortaleza, Brazil) and Colombian Ministry of National Health resolution 008430 of 1993. The study was approved by the ethics committee of each participating centre.

According to articles 10 and 11 of the above Resolution 008430 of 1993, the research is considered to come under the classification of being free of risk, and it is also a secondary-source study.

ResultsWe analysed 1,883 VCEs performed to investigate SB disease, from different centres around the country (Fig. 1). Out of all the procedures, 1,127 (59.9%) were performed in females and 756 (40.1%) in males. The mean age was 55.4 (SD: 18.5) with a range of 5.6–94.2 years.

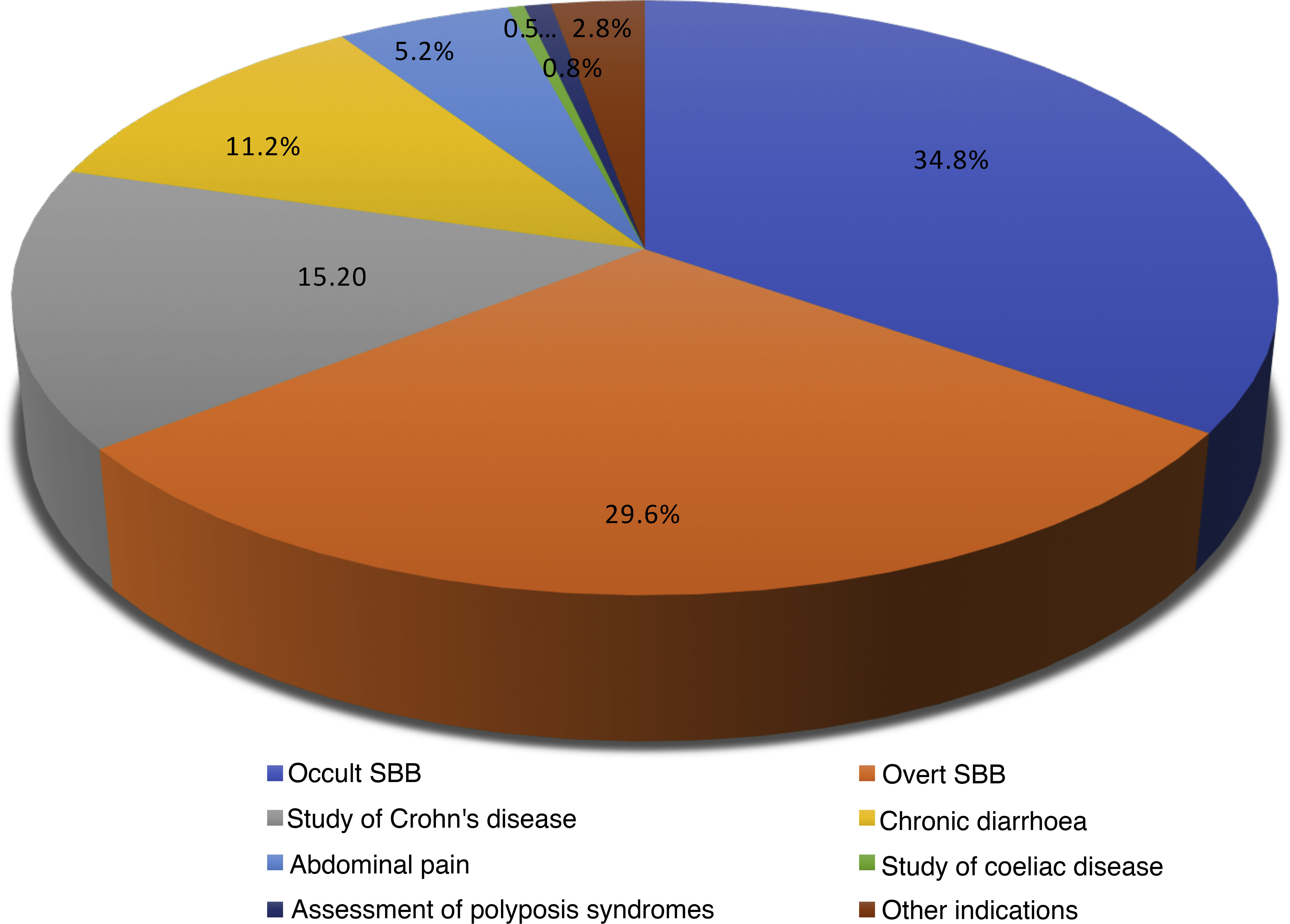

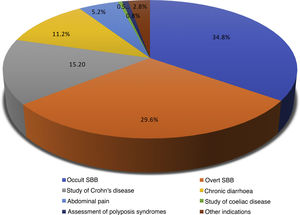

The most common indications for the VCE were suspected SBB in 1,212 (64.4%), 655 (34.8%) of whom had occult SBB and 557 (29.6%) overt SBB, investigation of CD in 286 (15.2%) and chronic diarrhoea in 210 (11.2%) (Fig. 2).

The VCE systems used were Medtronic SB2 and SB3 (96.0%), CapsoCam (3.5%) and Olympus EndoCapsule (0.5%). In 1,024 (54.3%) of the VCEs, laxatives were given for pre-procedure SB preparation (polyethylene glycol was used in 94.0%). In 859 (45.6%) of the cases, there was no preparation prior to the procedure.

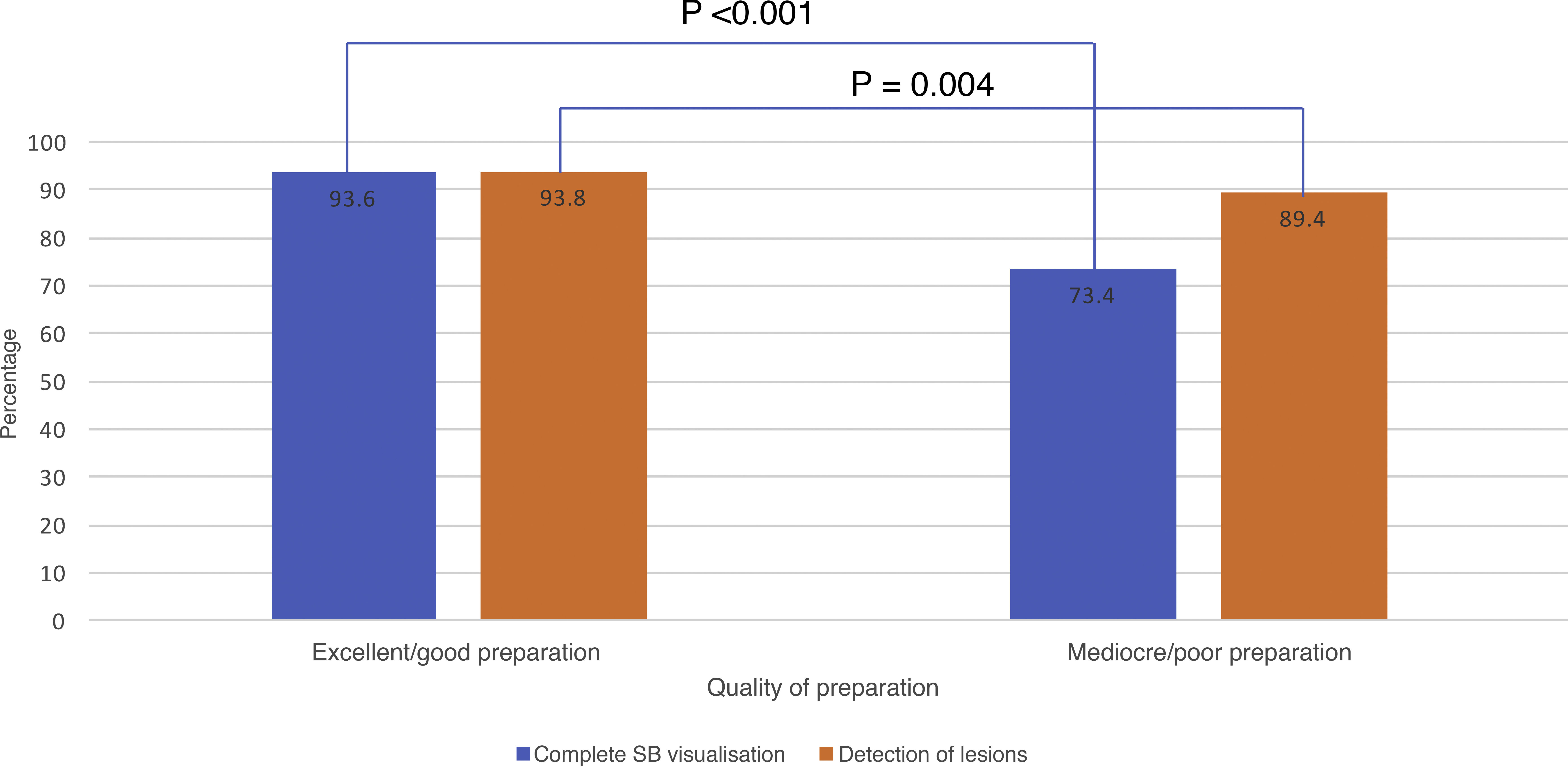

The qualitative quality of the SB mucosa preparation was considered excellent in 334 (17.7%), good in 1,416 (75.2%), fair in 111 (5.9%) and poor in 22 (1.2%). For the VCEs in which bowel preparation was carried out, the quality was classified as excellent/good in 94.8% vs 90.7% in the studies with no preparation. This difference was significant (OR=1.9; 95% CI: 1.3–2.7; p=<0.001).

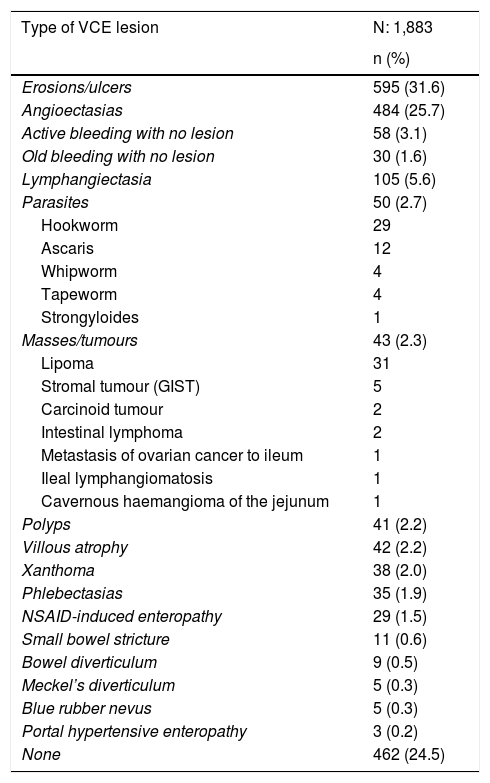

Out of 1,883 VCEs, lesions were detected in 1,421 (75.5%) and 462 (24.5%) were normal. The lesions found were as follows, in order of frequency with percentage of the total number of VCEs performed: erosions/ulcers (31.6%); angioectasias (25.7%); active bleeding without lesion (3.1%); old bleeding without lesion (1.6%); lymphangiectasia (5.6%); parasites (2.7%); masses/tumours (2.3%); polyps (2.2%); villous atrophy (2.2%); xanthoma (2.0%); phlebectasia (1.9%); non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced enteropathy (1.5%); small bowel stricture (0.6%); intestinal diverticula (0.5%); Meckel’s diverticulum (0.3%); portal hypertensive enteropathy (0.2%); and blue rubber nevus (0.3%) (Table 1). In 268 (14.2%) of the VCEs more than one type of lesion was found.

Types of lesions found in VCE.

| Type of VCE lesion | N: 1,883 |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Erosions/ulcers | 595 (31.6) |

| Angioectasias | 484 (25.7) |

| Active bleeding with no lesion | 58 (3.1) |

| Old bleeding with no lesion | 30 (1.6) |

| Lymphangiectasia | 105 (5.6) |

| Parasites | 50 (2.7) |

| Hookworm | 29 |

| Ascaris | 12 |

| Whipworm | 4 |

| Tapeworm | 4 |

| Strongyloides | 1 |

| Masses/tumours | 43 (2.3) |

| Lipoma | 31 |

| Stromal tumour (GIST) | 5 |

| Carcinoid tumour | 2 |

| Intestinal lymphoma | 2 |

| Metastasis of ovarian cancer to ileum | 1 |

| Ileal lymphangiomatosis | 1 |

| Cavernous haemangioma of the jejunum | 1 |

| Polyps | 41 (2.2) |

| Villous atrophy | 42 (2.2) |

| Xanthoma | 38 (2.0) |

| Phlebectasias | 35 (1.9) |

| NSAID-induced enteropathy | 29 (1.5) |

| Small bowel stricture | 11 (0.6) |

| Bowel diverticulum | 9 (0.5) |

| Meckel’s diverticulum | 5 (0.3) |

| Blue rubber nevus | 5 (0.3) |

| Portal hypertensive enteropathy | 3 (0.2) |

| None | 462 (24.5) |

Lesions were also found in sites other than the SB. Oesophageal lesions were found in 13 (0.7%) of the VCEs - 7 oesophageal varices, 2 erosive oesophagitis, 2 angioectasia and 1 oesophageal polyp. Gastric lesions were found in 52 (2.8%) - 32 erosive gastritis, 13 angioectasia, 5 active bleeding and 2 phlebectasia. Lastly, colonic lesions were found in 60 (3.2%) - 20 angioectasia, 5 active bleeding, 4 old bleeding, 19 erosive colitis, 1 colon cancer, 5 polyps, 2 parasites and 3 diverticular disease.

Sorting the detection rate by indication, of the 1,212 VCEs requested for suspected SBB, lesions were detected in 962 (79.3%), the most common being angioectasia in 345 cases (35.9%), followed by erosions/ulcers in 148 (15.4%). Of the 655 VCEs requested for suspected occult SBB, lesions were detected in 511 (78.0%), the most common being angioectasia (187; 36.6%), followed by erosions/ulcers (132; 25.8%). Of the 557 VCEs requested for suspected overt SBB, lesions were detected in 451 (76.8%), the most common being angioectasia (159; 35.3%), followed by erosions/ulcers (121; 26.9%). Of the 286 VCEs requested for suspected SB CD, lesions were detected in 235 (82.1%), the most common being erosions/ulcers (153; 65.3%), followed by angioectasia (43; 18.3%).

More angioectasias were found in VCEs indicated for suspected SBB, compared to VCEs for investigation of CD, and this difference was significant (OR: 2.24; 95% CI 1.6–3.2; p=0.000). The VCEs indicated for investigation of CD detected more erosions/ulcers compared to those for suspected SBB, with this difference also being significant (OR: 4.24; 95% CI 3.23–5.56; p=0.000).

Of the total of 1,212 VCEs indicated for suspected SBB, 250 were negative (20.6%), 227 (18.7%) showed P0 lesions, 372 (30.7%) P1 and 363 (29.9%) with P2. The diagnostic yield (P1+P2) of VCE for this group of patients was 60.6%. Of the 655 VCEs requested for suspected occult SBB, 144 (21.9%) showed P0 lesions, 217 (33.1%) P1 and 150 (22.9%) P2, for a diagnostic yield of 56.0%. Of the 557 VCEs requested for suspected overt SBB, 83 (14.9%) showed P0 lesions, 155 (27.8%) P1 and 213 (38.2%) P2, for a diagnostic yield of 66.0%. VCEs indicated for suspected overt SBB had a higher diagnostic yield than those for occult SBB, and this difference was significant (p=0.003).

In the VCE studies in which bowel preparation was excellent/good, a higher rate of SB lesions was detected than in those with fair/poor preparation (93.8% vs 89.4%), and this difference was significant (OR=1.8; 95% CI: 1.2–2.6; p=0.004) (Fig. 3). In 1,819 (96.6%) of the VCEs, complete SB visualisation was achieved, while in 64 (3.4%) it was incomplete. In the VCEs with complete SB visualisation, there was a higher percentage with excellent/good preparation than fair/poor preparation (93.6% vs 73.4%), and this difference was significant (OR=5.3; 95% CI: 2.9–9.5; p=<0.001) (Fig. 3).

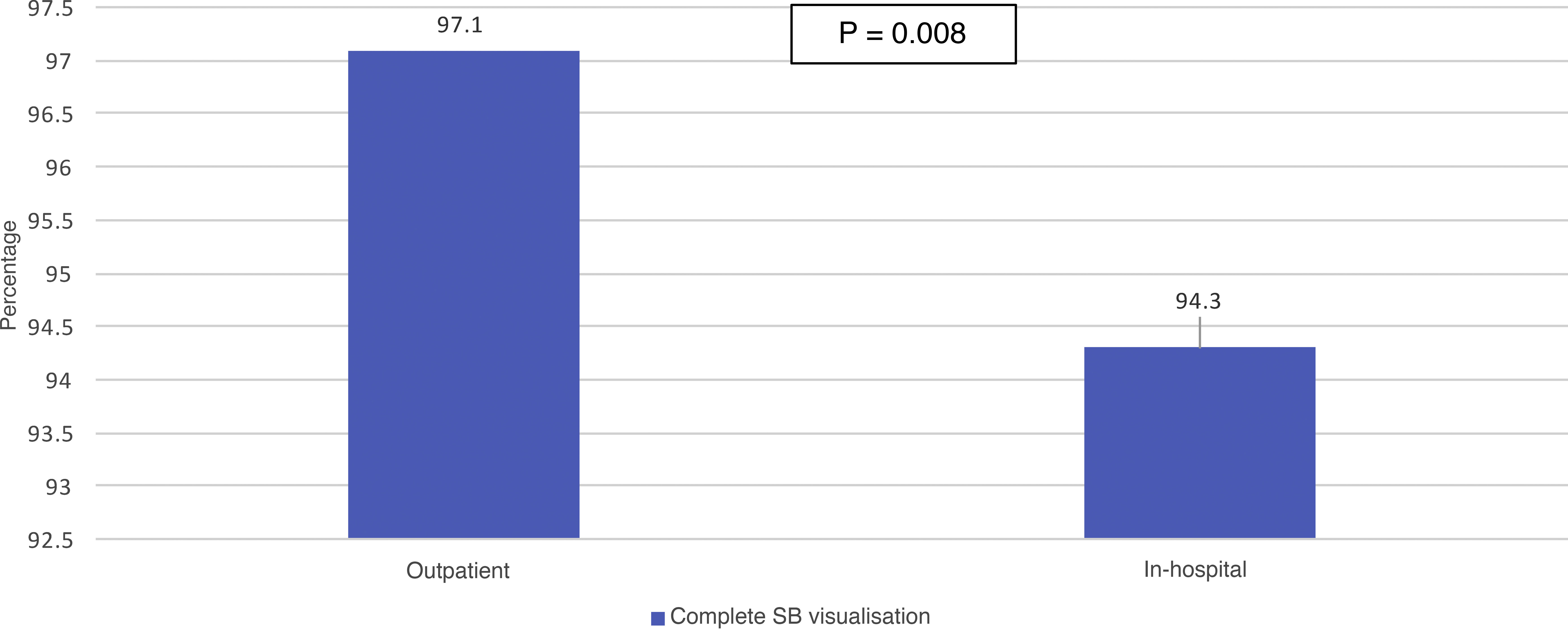

Of the total VCE studies performed, 349 (18.5%) were on hospitalised patients and 1,534 (81.5%) were carried out on an outpatient basis. Of the in-hospital VCEs, 329 (94.3%) were complete and 20 (5.7%) were incomplete. Among the outpatient VCEs, 1,490 (97.1%) were complete and 44 (2.9%) incomplete. Outpatient VCEs had a higher rate of complete SB visualisation than in-hospital VCEs (97.1% vs 94.3%), and this difference was significant (OR=2.1; 95% CI 1.2–3.5; p=0.008) (Fig. 4).

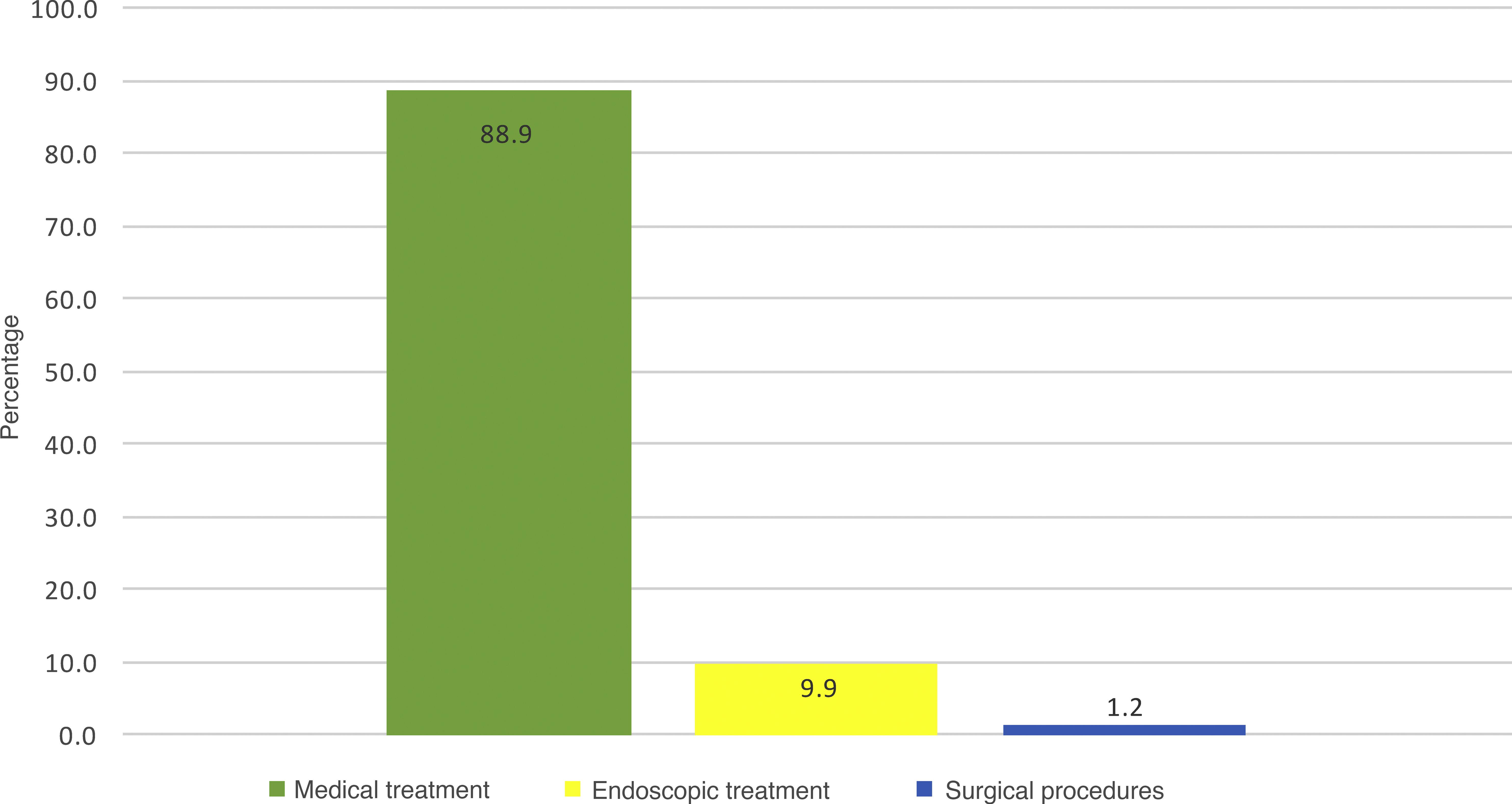

There were complications in 58 (3.1%) of the procedures. Bronchoaspiration occurred in eight patients (0.4%); in three of them the VCE had to be extracted by bronchoscopy, but the other individuals expelled it spontaneously. In 37 (2.0%) of the procedures, VCE retention in the stomach occurred, with all having to have the capsule moved on endoscopically. In 13 cases (0.7%), the VCE was retained in the SB for more than 15 days; the patients were monitored and in all of them the capsule passed to the colon spontaneously. There were no significant differences in terms of the indication for VCE and the rate of retention in SB (p=0.076). Of the 1,047 patients who went on to have treatment after the VCE, that treatment was medical in 931 (88.9%) and endoscopic in 104 (9.9%), with the remaining 12 (1.2%) having surgical procedures with SB resection (Fig. 5).

DiscussionIn this registry, 1,883 VCEs were analysed, for which the most common indication was suspected SBB (64.4%), followed by investigation of CD (15.2%), chronic diarrhoea (11.2%) and abdominal pain (5.2%). In a systematic review that included 227 publications on VCE, with more than 22,840 patients, the most common indication was OGIB (66.0%), according to the previously used classification, followed by investigation of CD (10.4%).6 In a more recent Korean national registry, the most common indication was also OGIB (64.4%), this time followed by abdominal pain (15.7%) and investigation of CD (only 4.6%).18 In a European multicentre study with 733 procedures, the most common indication was OGIB (55.4%), followed by diarrhoea (15.6%), abdominal pain (14.7%) and investigation of CD (4.9%).19 Our data are in line with those reported in the universal literature, with a slightly higher rate of VCE requested for investigation of CD, but this may be due to the participation in our registry of institutions which are national referral centres for the management of CD.

Debate continues to surround the use of bowel preparation for VCE. In this registry, preparation with laxatives, mainly polyethylene glycol, was prescribed in 54.3% of cases, and those who were prepared had better quality of mucosa visualisation compared to those simply prescribed liquid diet the day before. This difference was significant. In contrast to other studies, we also found a significant association between excellent/good quality preparation and higher rates of lesion detection and complete SB visualisation. A meta-analysis with 12 studies found greater diagnostic yield in patients who received preparation with laxatives compared to those simply prescribed clear liquids the day before the study, but did not demonstrate a higher rate of complete SB visualisation.20 A second more recent meta-analysis with 40 studies did not find significant differences in diagnostic yield or in the rate of complete SB visualisation, but they did demonstrate better visualisation quality in examinations with laxative preparation, compared to those prepared with only a clear liquid diet.21

Of the total of 1,883 VCEs carried out, no lesions were found in 24.5%, a rate similar to that found in other series. In the Korean study mentioned above18 36.2% of studies were found to be negative, and in 260 studies at the Mayo Clinic (Arizona, USA), 24% were normal.22 In our study, of the total VCEs performed, the most common lesions detected were erosions/ulcers (31.6%) and angioectasias (25.7%). The Korean national registry found angioectasias in only 9.7% of the VCEs performed and erosions/ulcers in 18.3%.18 In 260 VCEs with the sole indication of suspected OGIB, the previously cited Mayo Clinic study22 found SB angioectasias and ulcers in 61% and 17%, respectively.

In our registry, a high lesion detection rate (75.9%) was found in patients with suspected SBB. However, it is important to establish the clinical relevance of the lesions found.23 To do so, we used the previously discussed Saurin classification (P0, P1, P2), specifically designed for that purpose and to measure the diagnostic yield.17 Regarding the relevance of the lesions found, for the suspected indication of SBB in our registry, the diagnostic yield was 60.6%. VCE yield was higher in patients with suspected overt SBB than suspected occult SBB (66.0% vs 56.0%). In the original study by Saurin,17 they found a diagnostic yield of 67.2% in patients with OGIB. In the previously mentioned systematic review, the detection rate in OGIB was 60.5%, very similar to that reported in our registry.6 A systematic review of 24 VCE studies in patients with IDA found a diagnostic yield of 47%, with the most common lesions detected being vascular (31%) and inflammatory (17.8%).7 These figures are slightly lower than the diagnostic yield for occult SBB in our study.

The complete SB visualisation rate in our national registry was 96.6% and the SB capsule retention rate was 0.7%. We found no significant differences between the type of indication for VCE and the retention rate. A European multicentre study of 733 VCEs found a complete visualisation rate of 85.1% and a retention rate of 1.9%.19 A study at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona of 260 VCEs found a complete visualisation rate of 76% and retention rate also of 1.9%.22 A Swedish study including 2,300 VCEs found a complete visualisation rate of 80% and capsule retention in 1.3%, with this being more common in patients with CD and tumours.24 In a recent Korean study,25 out of 2,705 VCEs, they found a retention rate of 0.7%, the same figure as in our registry. A systematic review mentioned earlier found a complete SB visualisation rate of 83.5% and a retention rate of 1.4%.6 A more recent meta-analysis found a capsule retention rate of 2.1% in VCE for suspected SBB, and 3.6% in procedures for suspected small bowel CD.10 The above differences may be explained by the fact that our VCE procedures were more recent, the majority during this decade, and at all our centres we are able to track the movement of the capsule in real time, so we know when it passes into the duodenum. Also, the outpatient stays in the hospital or clinic until we verify that the capsule has progressed to the SB, and if it remains in the stomach for more than two hours, we move it on to the duodenum endoscopically, which increases the SB visualisation rate. Moreover, the newer VCE models have a longer battery life, increasing the potential duration of the examination, and allowing more time for the capsule to reach the caecum. This was demonstrated in the Korean national registry where, in 4,650 VCE procedures, the incomplete visualisation rate was 16% overall, with a retention rate of 3%, but they found a lower rate of incomplete visualisation in those performed from 2014 to 2019 compared to those from 2002 to 2014 (9.4% vs 18.9%, p<0.001).18

The retention rate in our registry is very low in comparison with other studies. In Colombia, we have had magnetic resonance enterography available for several years now for assessment of patients with obstructive bowel symptoms. This allows detection of the presence of strictures in a high percentage of cases, which would then contraindicate the use of VCE, thereby reducing the risk of retention.

In our study, outpatient VCE had a higher rate of complete SB visualisation than VCE in hospitalised patients (97.1% vs 94.3%), with this difference being significant. A study in Chicago (USA) comparing outpatient with in-hospital VCE, found that 90.5% vs 69.6% of the procedures respectively reached the caecum, this difference also being significant (p<0.001).26 This may be explained by hospitalised patients being acutely ill, receiving medications and having more restricted mobility compared to outpatients.

The main limitation of our study is that it was cross-sectional and was therefore susceptible to selection bias. Also, being a multicentre study, the interpretation of the type of lesions may vary according to the criteria used by the different interpreters of VCE lesions at each centre. International expert consensus was recently reached on nomenclature for vascular and inflammatory lesions, and this will hopefully lead to better description of the lesions and greater interobserver agreement among VCE readers.27,28

The results of this national registry (in brackets) comply with quality measures recently proposed by the European Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, such as a lesion detection rate >50% (75.5%), a caecum visualisation rate >80% (96.6%) and a capsule retention rate <2% (0.7%).29

ConclusionsIn this Colombian registry, 1,883 VCE procedures were analysed, making it the largest national VCE registry in Latin America. The indications, findings and diagnostic yield of VCE in Colombia are similar to those reported in the universal literature, with a slightly higher rate of VCE requested for investigation of CD compared to other studies for the reasons already mentioned. In addition, 2.7% of the VCEs in our registry had findings of parasites, which is very rarely reported in studies from developed countries. We also found a high percentage of studies with visualisation of the caecum and a low rate of complications. VCEs performed with preparation prior to the procedure showed better quality of SB mucosa cleansing, and this was associated with more detection of SB lesions and a higher rate of complete studies.

Our study provides valuable information on the study of SB disease with VCE in clinical practice in Latin America.

Authors/contributorsF. Juliao-Baños: study design, data acquisition and writing of the manuscript.

M.T. Galiano: data acquisition and review of the manuscript.

J. Camargo: data acquisition and review of the manuscript.

G. Mosquera-Klinger G: data acquisition and review of the manuscript.

J. Carvajal, C. Jaramillo, L.C. Sabbagh, H. Cure, F. García, B. Velasco, C. Manrique, V. Parra and C. Flórez: data acquisition.

J. Bareño: statistical analysis and review of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Juliao-Baños F, Galiano MT, Camargo J, Mosquera-Klinger G, Carvajal J, Jaramillo C, et al. Utilidad clínica de la videocápsula endoscópica en el estudio de patologías de intestino delgado en Colombia: resultados de un registro nacional. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:346–354.