Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) is a non-invasive diagnostic technique whose use in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has spread. A panenteric capsule, PillCam Crohn's (PCC), has recently been developed. We lack information on the availability and use of the CEID and PCC in our environment.

MethodsWe conducted an electronic and anonymous survey among the members of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] and the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology], consisting of 37 multiple-choice questions.

ResultsOne hundred and fifty members participated, the majority dedicated to IBD (69.3%). 72.8% worked at centres with an IBD unit. 79% had SBCE available at their hospital, 14% referred patients to another centre; 22% had a PCC available, 9% referred patients to another centre. 79.3% of respondents with available ICD used it in a small percentage of patients with IBD and 15.6% in the majority. The most frequent scenarios were suspicion of Crohn's disease (76.3%), assessment of inflammatory activity (54.7%) and assessment of the extent of the disease (54.7%). More than half (59.7%) preferentially used the Patency capsule to assess intestinal patency. Almost all respondents (99.3%) considered that training resources should be implemented in this technique.

ConclusionsSBCE is widely available in Spanish hospitals for the management of IBD, although its use is still limited. There is an opportunity to increase training in this technique, and consequently its use.

La cápsula endoscópica de intestino delgado (CEID) es una técnica diagnóstica poco invasiva cuyo empleo en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) se ha extendido. Se ha desarrollado recientemente una cápsula panentérica, PillCamCrohn’s (PCC). Carecemos de información sobre la disponibilidad y uso de la CEID y PCC en nuestro medio.

MétodosRealizamos una encuesta electrónica y anónima entre los miembros del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa y la Asociación Española de Gastroenterología consistente en 37 preguntas de respuesta múltiple.

ResultadosParticiparon 150 miembros, la mayoría con dedicación especial a la EII (69,3%). El 72,8% trabajaban en centros con unidad de EII. El 79% tenían la CEID disponible en su hospital, 14% derivándolo a otro centro. Un 22% tenía disponible la PCC, 9% derivándola a otro centro. El 79,3% de encuestados con CEID disponible la utilizaban en un pequeño porcentaje de pacientes con EII y un 15,6% en la mayoría. Los escenarios más frecuentes fueron la sospecha de Enfermedad de Crohn (76,3%), la valoración de actividad inflamatoria (54,7%) y la evaluación de la extensión de la enfermedad (54,7%). Más de la mitad (59,7%) utilizaban preferentemente la cápsula Patency para valoración de la permeabilidad intestinal. Casi todos los encuestados (99,3%) consideraba que se deberían implementar recursos formativos en esta técnica.

ConclusionesLa CEID cuenta con una amplia disponibilidad en los hospitales españoles para el manejo de la EII, si bien su uso es todavía limitado. Existe una oportunidad para aumentar la formación en esta técnica, y con ella, el empleo de la misma.

Small bowel (SB) involvement is present in more than half of the patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease (CD),1 and the percentage of proximal involvement within the reach of ileocolonoscopy (L4 of the Montreal classification) is higher than 20%.2

This type of lesion has always been a diagnostic challenge with prognostic implications, as it is more frequently associated with the development of a stenosing phenotype and greater surgical requirements.3,4

Since the small bowel endoscopy capsule was approved in 2001 by the European Medicines Agency, its use has expanded to become a first-line diagnostic tool in the evaluation of CD of the SB. Small bowel capsule endoscopy (SBCE) is a minimally invasive technique, preferred by patients5 and with a low rate of adverse effects. The main advantage of SBCE is its high negative predictive value, close to 100%, although the high sensitivity of the technique has the disadvantage that it is difficult to interpret subtle lesions, such as aphthous ulcers, which can be present in up to 10% of healthy individuals. For this reason, it is important to select properly the patients for performing SBCE, when it is used in the diagnosis of CD, and to correlate properly with the clinical context, when it is indicated in a patient with known CD, in order to avoid overdiagnosis. The main adverse effect is device retention, which occurs in 3.6% of patients with suspected CD and in 8.2% of patients with established CD, but this is mostly resolved with conservative management.6 Retention can be prevented with the use of the Patency® capsule (PC), a biodegradable capsule morphologically identical to the SBCE, which begins to spontaneously disintegrate after 30 h within the body. If the PC is not completely expelled, it is considered a negative patency test and contraindicates the SBCE procedure due to the risk of retention.7

It is currently recommended to perform an SBCE or an imaging test in patients with clinical suspicion of CD with a normal initial ileocolonoscopy and in all newly diagnosed patients for the proper assessment of the SB, as an extension study.8 Another scenario for indicating SBCE is to monitor postoperative recurrence,9 with little data published on its role in evaluating mucosal healing or in the approach to therapeutic de-escalation.10

In recent years, a new pan-enteric capsule model, the PillCam Crohn’s (PCC) capsule, capable of viewing the entire digestive tract, has been developed and has shown its safety and feasibility.11

Although some aspects are still disputed, we currently have recent guidelines on both the indications and the use of SBCE12 and on its specific role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).8 However, we do not have information about the use of SBCE in routine clinical practice in our setting, the availability of the technique, the use of the PC or the bowel preparation used prior to the procedure. The objective of the study was, therefore, to evaluate the main aspects of the use of SBCE in clinical practice in our setting.

MethodsAn electronic survey was designed consisting of 37 questions that covered the most important aspects of the use of SBCE. The survey population consisted of the 1000 members current at the time of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] and the 1234 members of the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology]. The project was approved by the scientific committees of both associations (GETECCU and AEG). The questions were designed to collect information on the availability of the technique, the scenarios in which it is used in routine clinical practice, the assessment of intestinal patency, the type of bowel preparation prior to the procedure and, finally, aspects related to the interpretation of the images and technical training.

Between July and August 2020, a total of five invitations between the two scientific societies were sent through their respective technical secretariats by email. The survey was designed on the digital platform Cognito Forms (www.cognitoforms.com), which enables the secure creation of digital surveys with the ability to export the database to the main statistical programs. Participation was completely voluntary and anonymous, with it being possible to identify the participants by any means.

For the statistical analysis of the quantitative variables, the mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated, or the median and interquartile range (IQR) if they did not follow a normal distribution, and the qualitative variables were described using proportions. To compare the responses according to subgroups, the chi-square test was used, considering values of P < .05 as statistically significant. Statistical calculations were performed with the statistical program IBM SPSS Statistics, version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

ResultsA total of 150 members participated, with a mean age of 41 years (SD: 9.4), of which 65.3% were women. The mean experience for participants as digestive system specialists was 11.9years, and 69.3% reported a special dedication to IBD with an average duration of seven years (SD: 7.5). The majority (72.8%) work in a hospital or centre with an IBD unit.

Availability of the techniqueSBCE was available for 92.7% of the participants, for the majority (84.9%) within their service, while 15.1% needed to refer the patient to another centre. Among the participants for whom it was not available (7.3%), 27.7% of them expected to have it available in the near future (months).

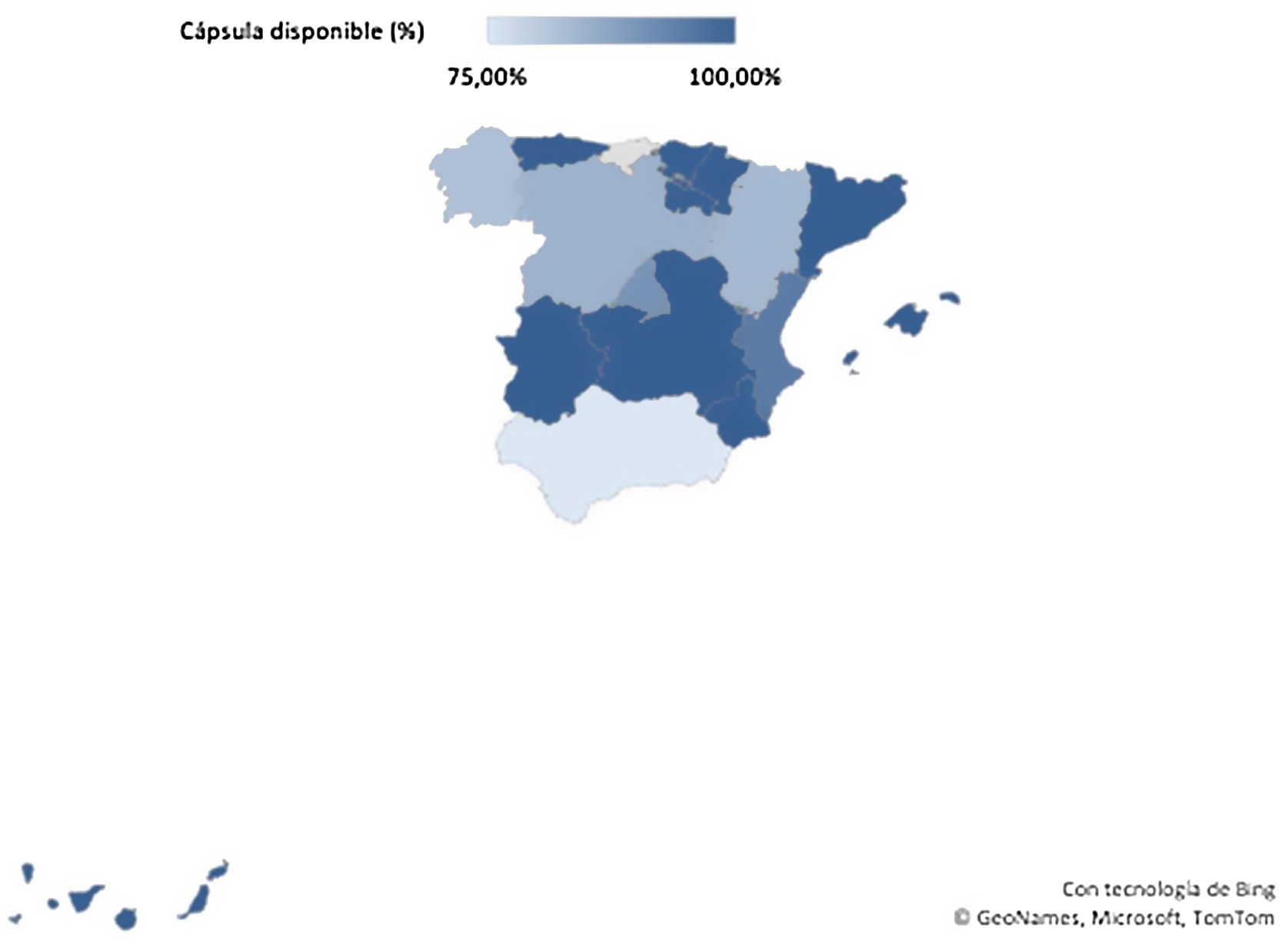

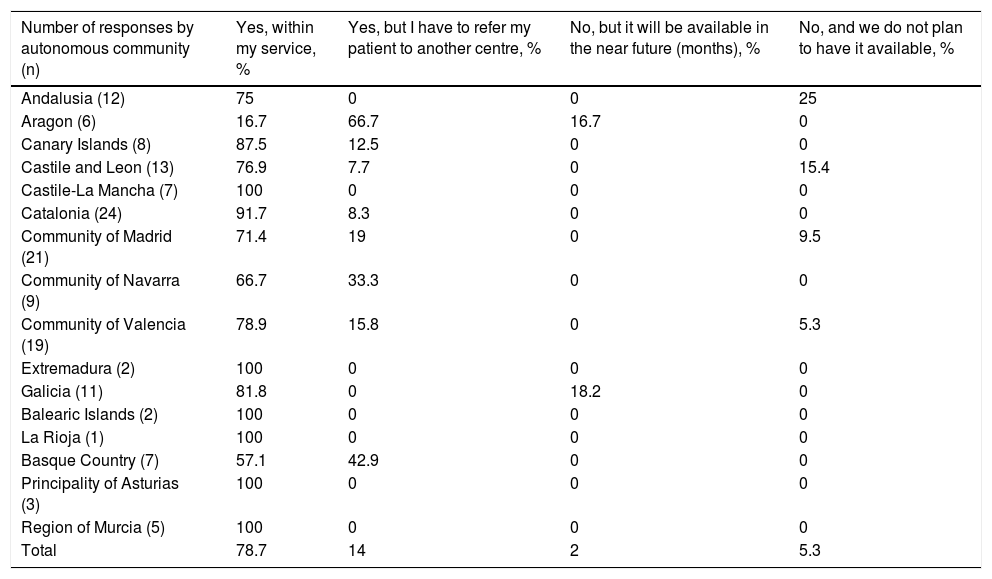

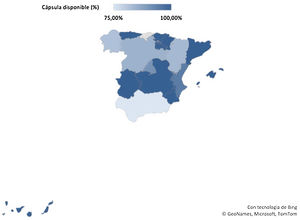

The technique's availability by autonomous communities is shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The technique had been available to specialists for a median of 8.8 years (IQR 0–18 years), with the oldest reported incorporation of the technique in May 2002 and the most recent in June 2020. In the last year, the approximate total number of SBCEs carried out in the respective centres of each participant was less than 100 in 62.1%, and between 100 and 300 in 30.7%, obtaining a marginal percentage of 5.7% and 1.4% in the categories of 300–500 and more than 500 procedures, respectively.

Availability of the technique by autonomous community.

| Number of responses by autonomous community (n) | Yes, within my service, % | Yes, but I have to refer my patient to another centre, % | No, but it will be available in the near future (months), % | No, and we do not plan to have it available, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalusia (12) | 75 | 0 | 0 | 25 |

| Aragon (6) | 16.7 | 66.7 | 16.7 | 0 |

| Canary Islands (8) | 87.5 | 12.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Castile and Leon (13) | 76.9 | 7.7 | 0 | 15.4 |

| Castile-La Mancha (7) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Catalonia (24) | 91.7 | 8.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Community of Madrid (21) | 71.4 | 19 | 0 | 9.5 |

| Community of Navarra (9) | 66.7 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 |

| Community of Valencia (19) | 78.9 | 15.8 | 0 | 5.3 |

| Extremadura (2) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Galicia (11) | 81.8 | 0 | 18.2 | 0 |

| Balearic Islands (2) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| La Rioja (1) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Basque Country (7) | 57.1 | 42.9 | 0 | 0 |

| Principality of Asturias (3) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Region of Murcia (5) | 100 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 78.7 | 14 | 2 | 5.3 |

With regard to the PCC, 22% (n = 33) of those surveyed had it available (9% of them through referral to another centre), 16.7% expected to obtain it in the coming months and 61.3% did not plan to incorporate it. The median time since it had been available was 1.19 years (IQR 0–2), with January 2018 being the oldest incorporation date and July 2020 the most recent. The total number of procedures performed was less than 10 in 38.5%, between 10 and 20 in 30.8%, and between 30 and 40 in 19.2%. Only one respondent reported having performed between 40 and 50 procedures, and two participants reported more than 50 PCCs.

Indications for SBCE in IBDAmong the 139 participants with SBCE available, the majority (79.3%) only used it in a small percentage of their patients. Only 15.6% performed the procedure in most of their patients, the options for use being marginal in all patients (2.2%) or none (3%).

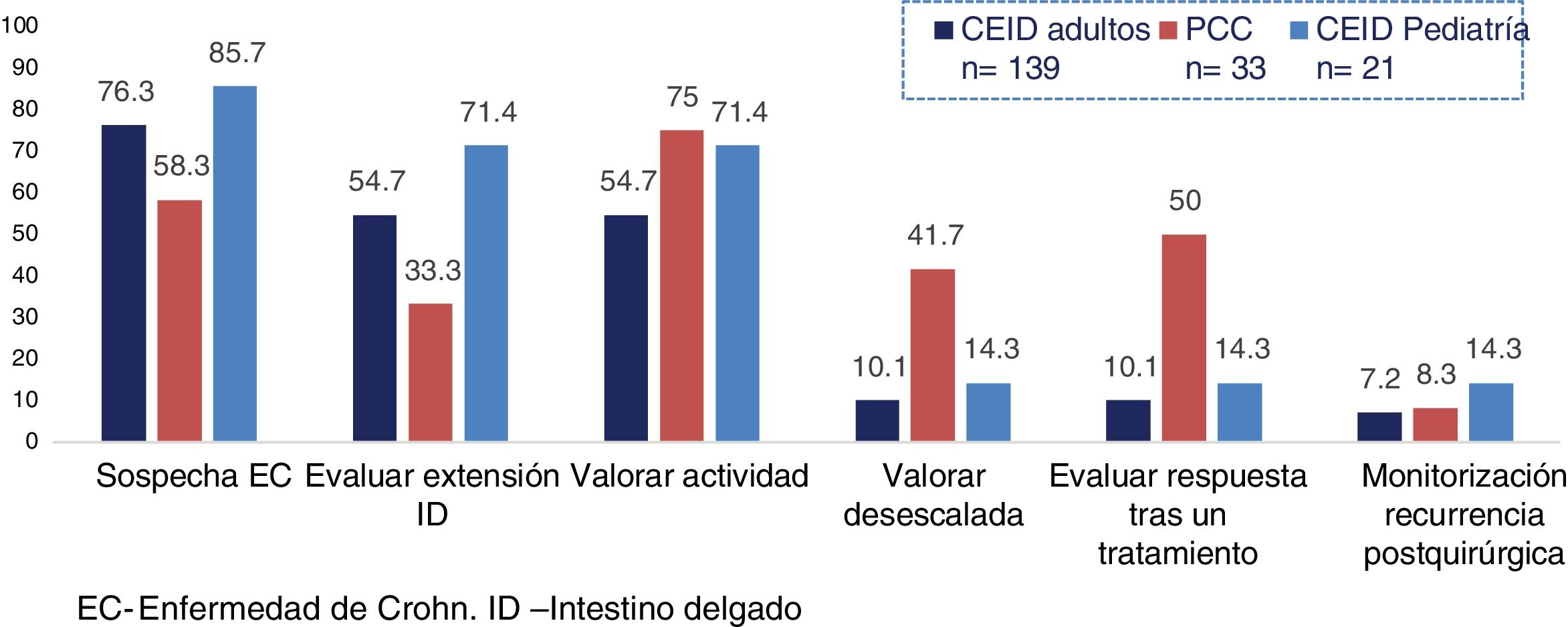

The most widely used scenarios were suspicion of CD (76.3%), assessment of inflammatory activity due to clinical or biochemical suspicion (54.7%), and evaluation of the extent of the disease (54.7%). Overall, 10.1% of participants used SBCE both in the assessment prior to therapeutic de-escalation and in the response to treatment, the percentage being significantly higher in the centres that performed more than 100 procedures per year (17% vs 5.7%; P = .03). In addition, 7.2% performed it in the monitoring of postoperative recurrence.

The indications for the use of the PCC and SBCE in the paediatric population differed slightly compared to SBCE in adults (Fig. 2). In paediatrics, the main difference was a greater use of SBCE to evaluate the extension after diagnosis (71.4% vs 54.7%; P = .14) and to assess activity (71.4% vs 54.7%; P = .14), both differences without reaching statistical significance. In the case of the PCC, it was used in a lower percentage when there was suspicion of CD (58.3% vs 76.3%; P = .03) and more for the assessment of activity in the event of clinical/biochemical suspicion (75% vs 54.7%, P = .03) and prior to therapeutic de-escalation (41.7% vs 10.1%; P < .001), in a statistically significant way.

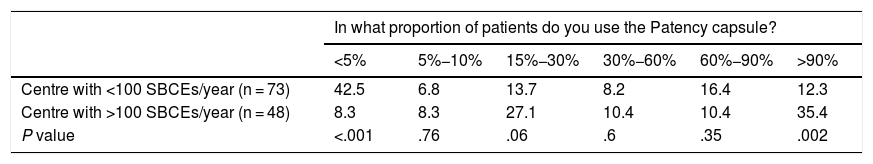

Assessment of intestinal patencyThe PC was available for 84.2% of those surveyed. For the assessment of intestinal patency prior to the procedure, 59.7% preferably used the PC, compared to 49.6% who used magnetic resonance enterography. Only 9.4% assessed patency by intestinal ultrasound.

Statistically significant differences were found (P < .001) depending on the number of annual examinations carried out in each centre, with the PC being less used among those surveyed from centres where fewer than 100 SBCEs were performed per year (Table 2).

Use of the Patency® capsule.

| In what proportion of patients do you use the Patency capsule? | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <5% | 5%−10% | 15%−30% | 30%−60% | 60%−90% | >90% | |

| Centre with <100 SBCEs/year (n = 73) | 42.5 | 6.8 | 13.7 | 8.2 | 16.4 | 12.3 |

| Centre with >100 SBCEs/year (n = 48) | 8.3 | 8.3 | 27.1 | 10.4 | 10.4 | 35.4 |

| P value | <.001 | .76 | .06 | .6 | .35 | .002 |

Overall, 89.6% used the PC in cases of suspicion of stenosis on imaging, 85.2% in cases of obstructive symptoms, and 76.5% in patients with CD with a previous stenosing and/or penetrating pattern. There were no statistically significant differences by centres with/without an IBD unit or in cases of special dedication to IBD.

Bowel preparationTo be able to evaluate the colon, all patients required bowel preparation with laxatives and all respondents administered preparation when using the PCC. Regarding SBCE, 39.1% of those surveyed did not use laxatives, limiting bowel preparation to a light meal the day before, a diet of clear fluids the previous afternoon/evening and fasting. The remaining 60.9% used laxatives, mainly polyethylene glycol (79.4%), followed by sodium picosulfate (16.6%). Two patients used macrogol solutions.

The respondents reported a higher percentage in the use of prokinetics than of antifoaming agents, both in the SBCE (40.2% use of prokinetics vs 28.7% use of antifoaming agents; P = .11) and in the PCC (54.5% vs 31.8%; P = .2).

Capsule endoscopy trainingAt the centres of the participants where SBCE was available, there was an average of 2.3 gastroenterologists trained in how to read one. Among these, 46.8% learned through a face-to-face training course, 38.2% in the daily practice of a hospital (27.6% in the same hospital and 10.6% while on an external rotation at another centre) and 14.8% were self-taught.

In all, 99.3% of those surveyed considered that national scientific societies should provide training resources for learning this technique: 36% in the form of online courses and other e-learning resources, 11.3% in the form of face-to-face courses and 52% through any of the above options. The main areas for training improvement according to the participants were interpretation of imaging (93.2%), reading technique (84.2%), clinical cases (76.7%) and indications/contraindications (75.3%). The demand for training was less frequent for complications (60.3%), the PC (56.8%), material and implementation of the technique in the hospital (55.5%), the PCC (53.4%) or use in paediatrics (36.3%).

In most cases (64.1%), the images were interpreted by a gastroenterologist within the service without special dedication to IBD, while in 23.9% of cases the reading was made by a gastroenterologist from the IBD unit. There were no cases of images being interpreted by the nursing staff, and 12% did not know (SBCE referred to another hospital). When asked who should interpret the images, 65.7% of those surveyed believed that it should be a gastroenterologist from the IBD unit, followed by a non-specialised gastroenterologist (25%). Five cases (3.6%) considered that they should be interpreted by the nursing staff under the supervision of a gastroenterologist from the IBD unit.

Regarding the endoscopic indices used in the report, the most popular was the Lewis index13 (30.5%), followed by the Capsule Endoscopy Crohn's Disease Activity Index (CECDAI)14 (4.7%). Overall, 5.5% used any of the above interchangeably, while in most cases (59.4%) none were usually used. In total, 72.3% of those who used indices considered them to be very necessary, compared to 27.6% who considered that they did not provide advantages over an adequate description in the report. Among those surveyed who did not use them, 71.2% believed that they should, while the rest (28.7%) believed them to be unnecessary if a good description was available in the report.

Among the participants who used the PCC, 54.5% considered that the new software made a real difference in the interpretation and follow-up of patients with IBD.

DiscussionDespite the usefulness of SBCE in the diagnosis and follow-up of IBD, little data is available on access to and use of the technique in patients with IBD in Spain. In 2015, Marin-Jimenez et al.15 published the results of a survey on the use of diagnostic techniques in IBD, which included SBCE, highlighting its low availability (63.1% of gastroenterologists) in our setting and recommending extension of the technique to boost access to it. The present study reveals a greater implementation of the technique, which is currently available to 92.7% of those surveyed. Although it is true that there are slight differences between autonomous communities, all of them show greater accessibility than that reported five years ago. With regard to the PCC, it seems to be becoming more well known in our country, with more than 20% of those surveyed having it among their diagnostic options and expecting to incorporate it in 16.7% more cases in the near future.

Not only is SBCE available to the participants, but practically all (97%) use it in routine clinical practice, although the majority do so in a small subgroup of patients who would benefit from the procedure. The main indications for SBCE are consistent with clinical practice guidelines,8 such as for the diagnosis of CD after normal ileocolonoscopy and for assessing the extent of SB involvement. Another notable indication is for the confirmation of activity, since in CD the correlation between symptoms and inflammatory activity at the SB level is suboptimal16 and SBCE is minimally invasive and well-accepted by the patient5 for determining whether the symptoms are secondary to the disease activity.

The scenarios change with the PCC. On the one hand, it is used less in the case of suspected CD, since in most cases the patient has previously undergone a colonoscopy and, therefore, colonic evaluation using the capsule would not be necessary. On the other hand, its use is more frequent to assess activity in the event of a suspected flare-up, since the PCC has the advantage of allowing the assessment of both the SB and the colon in a single examination.

One disputed aspect is bowel preparation prior to the procedure, as reflected in the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) review of 2018.12 Initially, the use of laxatives prior to SBCE was not recommended, but only a low fibre diet the day before and fasting of 12 h. Subsequent studies summarised in four meta-analyses17–20 have concluded that the ingestion of 2L of polyethylene glycol (PEG) solution improved the visibility of the mucosa, with the evidence regarding a higher rate of complete examinations or better diagnostic performance being inconclusive. The ESGE currently recommends dietary modification and 2L of PEG without establishing the optimal time to take the laxatives.12 However, in our series only 60.9% of the respondents used laxatives in the preparation. Additionally, the ESGE recommends the use of simethicone, since this improves mucosal visualisation9,10 and reduces possible artifacts secondary to foam or bubbles.21 It does not routinely recommend the use of prokinetics, reserving them for patients at high risk of incomplete exploration, such as in abdominal surgery, delayed gastric emptying, diabetic neuropathy or hypothyroidism. Our results show a higher percentage in the use of prokinetics than antifoamng agents in SBCE. It should be noted that 71.3% of the participants never use antifoamng agents, which points to a possible area for improvement, although the optimal dose of simeticone is still unknown.

Endoscopic indices are used with the intention of standardising the description of lesions in reports based on structured terminology, providing a reproducible methodology for interpretation and the estimation of endoscopic activity. In SBCE, it is recommended to use validated indices, such as the Lewis13 or the CECDAI,14 since they allow a decrease in interobserver variability. However, our study shows up the scarce implementation of these indices, given that a high proportion of those surveyed do not use any of them, although they think that they should. This is an aspect that most likely could be improved with the implementation of capsule endoscopy training resources and with the reading of studies by gastroenterologists dedicated to IBD, who are more used to managing the indices of the disease.

Capsule retention, although preventable, is the main complication of the technique. For most of the respondents (84.2%), the PC is available to assess patency. Although the most recent studies advocate using the PC only in patients in whom there is a clinical or radiological suspicion of stenosis or a history of surgery (selective strategy), as opposed to the non-selective strategy that involves using the PC in all patients diagnosed with CD in whom an SBCE is going to be carried out,22–24 this issue is still controversial. Among our participants for whom the PC was available, 21.5% used it in more than 90% of their patients, and this percentage reached 35% at the centres that perform more than 100 SBCEs per year.

From all this, it follows that there is also room for improvement in this aspect. On the one hand, the absence of PC availability for almost 20% of those surveyed may imply that a study with SBCE is not indicated in many patients, since the use of radiological tests to assess intestinal patency may overestimate the risk of retention of the capsule.25 On the other hand, more than a third of the respondents from the centres where most examinations are carried out apply a non-selective strategy for indicating the PC. This could be a reflection of a more defensive attitude, derived from previous experiences of retention in other patients, although this strategy has not been shown to reduce the risk of retention.

The present study has revealed the great opportunity we have to increase capsule endoscopy training, since almost all the respondents (99.3%) consider that scientific societies should provide training resources for learning this technique, and that they should be directed primarily at IBD physicians, who should be encouraged to learn the technique. In view of the results, both traditional face-to-face courses and new e-learning resources are options accepted by the majority of respondents, with a slight preference for the latter form of online learning, although most of those who read capsule images learned how to do so on a face-to-face course. The areas for improvement chosen were mainly the interpretation of images, reading techniques and clinical cases, to be taken into account when preparing training content.

Regarding the limitations of the study, we must point out a relatively low percentage of responses among those invited to participate. Although we obtained 150 responses from a total of 2234 invitations, a not inconsiderable proportion of specialists belong to both scientific societies, although it has not been possible to obtain the exact figure for reasons of personal data protection. If we consider that there was no overlap between the two societies, our percentage of participation (6.7%) is below that of other surveys carried out in our setting, although in absolute numbers the number of responses was similar.26 The care overload due to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic situation is a factor that may have contributed to the rather low participation, since in these times the provision of care activities has predominated over other scientific activities.

On the other hand, the degree of availability could be overestimated taking into account the low participation of the surveyed group. It is possible that those who do not have the technique or do not know much about it refrained from answering the survey.

The main strength of the study is the wide geographic distribution of the responses, which allows us to make a good estimate of the situation throughout the country. It has allowed us to know the current state of the use of this technique, as well as to identify areas for improvement, especially in the training field. It also provides an answer to important aspects hitherto unknown, such as its use in paediatrics or the type of intestinal cleansing used in clinical practice.

We can conclude that SBCE is a technique that is widely available in Spanish hospitals for the management of CD, although its use is still limited. There is a great opportunity to increase its use and training in this technique, especially among gastroenterologists with special dedication to IBD.

Please cite this article as: Elosua González A, Nantes Castillejo Ó, Fernández-Urién Sainz I, López-García A, Murcia Pomares Ó, Zabana Y. Uso de la cápsula endoscópica en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal en práctica clínica en España. Resultados de una encuesta nacional. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:696–703.