The prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) continues to rise around the globe. Although the percentage of pediatric IBD patients seems to be increasing, rates are surprisingly heterogeneous among different populations. Although the pathogenesis of IBD is believed to be multifactorial, a genetic predisposition may be especially relevant in pediatric-onset IBD. Phenotypic characteristics can also be significantly different when comparing pediatric and adult-onset IBD. Patients that develop the disease at a younger age usually present with more extensive and more aggressive disease and develop complications faster when compared to those that develop it during adulthood. Children with IBD are found to have frequent mood disorders and have a higher risk of developing socio-economic hardship, failing to meet development milestones. Therefore, IBD management should always involve a multidisciplinary team that is not limited to medical providers. Most institutions do not have an established transition protocol and lack the resources and training for transition care. Although there is no consensus on an optimal timing to transition the patient's care to an adult team, it is usually accepted they should be eligible for adult care when most of the key transition points have been met. Management strategies should be tailored to each patient's developmental level and environment. A successful transition can improve the long-term outcomes such as sustained remission, medication adherence, mental health and social and academic performance, while decreasing healthcare utilization. Every institution that manages pediatric IBD patients should have a well-established transition protocol in order to make sure to maintain continuity of care.

La prevalencia de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) sigue incrementándose alrededor del mundo. Aunque el porcentaje de pacientes pediátricos con EII parece estar aumentando, las tasas son sorprendentemente heterogéneas entre diferentes poblaciones. Si bien, la patogénesis de la EII es multifactorial, una predisposición genética puede ser especialmente relevante en la EII de inicio precoz. Las características fenotípicas también pueden ser significativamente diferentes cuando se compara la EII pediátrica y adulta. Los pacientes que desarrollan la enfermedad a una edad más temprana generalmente presentan una enfermedad más extensa y de mayor agresividad e incluso pueden desarrollar complicaciones en forma precoz en comparación con aquellos que la desarrollan durante la edad adulta. Se ha descubierto que los niños con EII tienen trastornos del estado de ánimo frecuentes y tienen un mayor riesgo de desarrollar dificultades socioeconómicas y no alcanzar los hitos en el desarrollo. Por lo tanto, el manejo de la EII siempre debe involucrar a un equipo multidisciplinario que no se limite a los médicos. La mayoría de las instituciones no tienen un protocolo de transición establecido y carecen de los recursos y la capacitación para la atención de transición. Aunque no hay consenso sobre el momento óptimo para la transición de la atención del paciente a un equipo de adultos, generalmente se acepta que deben ser elegibles para la atención de adultos cuando se hayan cumplido la mayoría de los puntos clave de transición. Las estrategias de manejo deben adaptarse al nivel de desarrollo y entorno de cada paciente. Una transición exitosa puede mejorar los resultados a largo plazo, como la remisión sostenida, la adherencia a los medicamentos, la salud mental y el desempeño social y académico, al tiempo que disminuye la utilización de la atención médica. Cada institución que maneja pacientes pediátricos con EII debe tener un protocolo de transición bien establecido para asegurarse de mantener la continuidad de la atención.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a wide spectrum condition of the gastrointestinal tract that includes ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), and IBD-unclassified (IBDU). These diseases may present at any age, but a significant number of patients develop it during early years. IBD that develops in children and adolescents can have important differences when compared to those that develop during adulthood. For example, pediatric patients present with more extensive disease and more commonly with upper gastrointestinal tract involvement.1 Furthermore, the overall physical and psycho-social aspects in children are quite different than in adults. The pediatric population must go through unique developmental milestones that require special consideration, such as physical and psychological development. The transition from the pediatric to adult care system is a crucial phase in the management of IBD patients. Even though multiple guidelines are available, there is still no global consensus on how best to transition these patients. It is expected that every patient will have a different threshold to transition care. In order to better serve this population and to identify the optimal time to transition from pediatric to adult care, it is important to understand differences between both populations. In this review, we aim to summarize the most recent evidence looking into distinctions between pediatric and adult onset IBD and approaches that may facilitate the transition in a personalized fashion. An electronic literature search was carried out using Embase, Web of Science, and Pubmed for articles written in English and Spanish from the last 10 years. The keywords used were “Inflammatory bowel disease”, “child”, “transitional care”, “ulcerative colitis”, “Crohn's disease”. References and conference abstracts were searched to identify additional studies.

Differences between pediatric and adult patients with inflammatory bowel diseaseWhat we know about pediatric IBDThe prevalence of IBD continues to rise globally, even though the real proportion of pediatric-onset IBD is not known. Historical estimates commonly quote pediatric-onset IBD representing around 20–25% of IBD cases.2 Although global incidence rates appear to be increasing, the proportion of those patients that fall within the pediatric group is surprisingly heterogeneous among different populations.3 The highest rates of annual incidence of pediatric IBD are reported in Europe and North America, with up to 0.2–23/100,000 and 15.2/100,000 cases, respectively.4 In the United States, a study looking into a large national database reported an overall prevalence of pediatric IBD of 77.0 per 100,000 population in 2016. This represents an increase of 133% when compared to 33.0/100,000 in 2007.5 In contrast, regions with the lowest reported pediatric IBD incidence include Oceania (2.9–7.2/100,000), Asia (0.5–11.4/100,000), Latin America (0.2–2.4/100,000), and Africa (0.0–0.9/100,000).6 A recently published study conducted by the Latin American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (LASPGHAN) Working Group described epidemiologic trends in pediatric IBD from nine countries between 2005 and 2016. The annual incidence of UC increased 5.1 times, while that for CD, increased 3.4 times. Incidence rates of IBDU were very low from 2005 to 2010 and then slightly increased in 2011.7

Inflammatory bowel disease is through to be caused by the interaction of multiple environmental risk factors, the microbiome, and the immune system in a high-risk genetic background.8,9 In pediatric-onset IBD, the genetic setting may have a stronger significance when compared to adults. Three major areas have been raised regarding IBD genetics: common polygenic risk variants, rare monogenic IBD genetics, and pharmacogenetics.10 Evaluation of the complete set of genetic variants has defined over 230 locations of genes (disease loci) linked to IBD,9,11 the majority involve noncoding variation, many of which modulate levels of gene expression.12 Pediatric IBD is familial in 19–41% of cases and a family history is commonly present when CD is diagnosed before 11 years of age.13 A growing number of rare monogenic IBD disorders has been identified, although they still account for a minority of children with IBD, including primary immunodeficiencies and intestinal epithelial cell defects.9,14,15

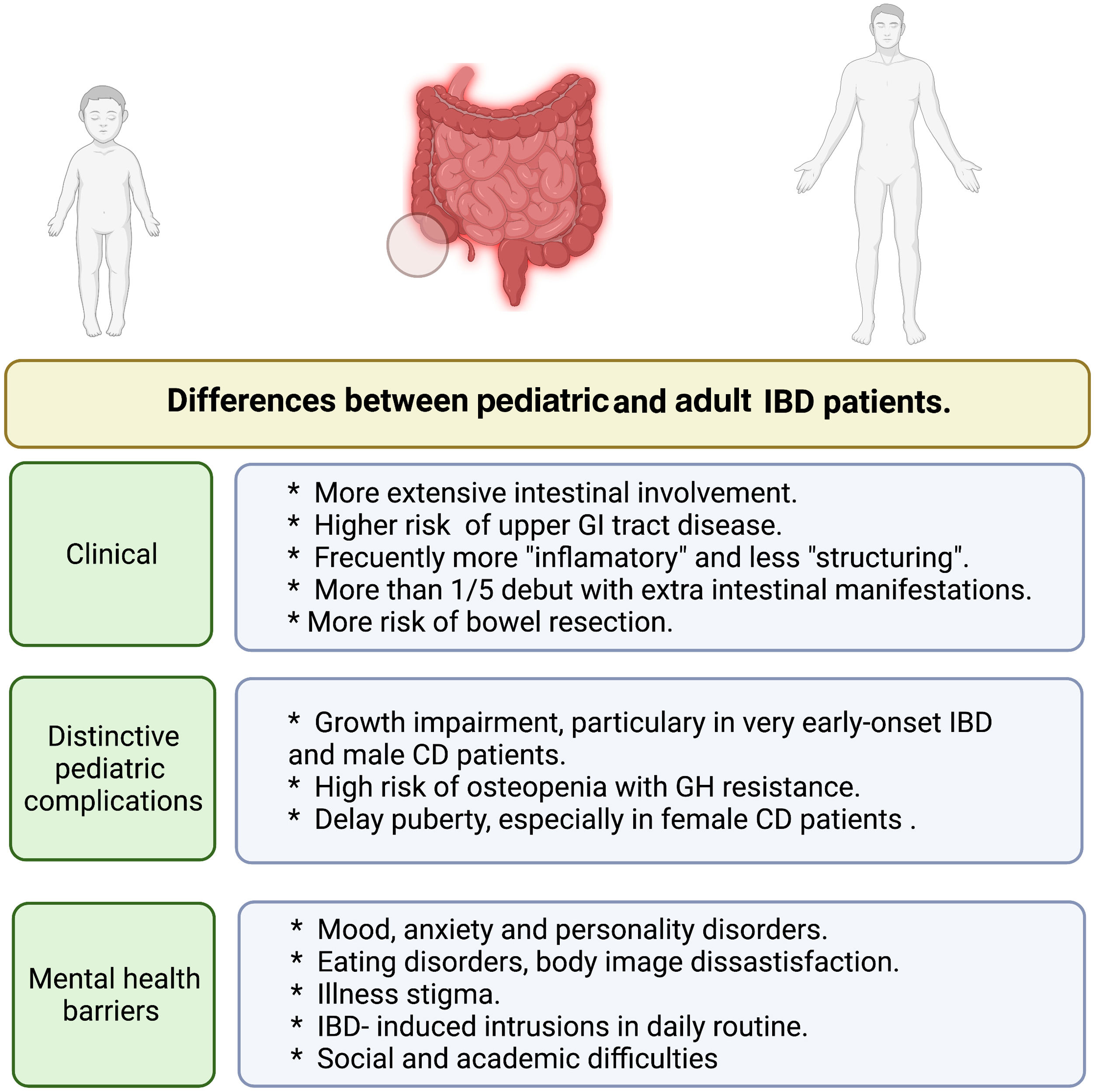

Unique differences in pediatric-onset IBDThere are some significant phenotypic differences between children and adult IBD disease resulting in distinctive challenges. Children are more likely to have a more extensive amount of involved bowel. For example, when compared to adults, over 80% of pediatric patients that develop UC present with pancolitis, and UC is rarely restricted to the rectum.16,17 Disease extension and earlier age at diagnosis are considered relevant prognostic factors.18 Children are more likely to be hospitalized for UC, especially around the time of diagnosis and have a higher risk of requiring colectomy within the first years of the disease.19

In CD, children are more likely to have colonic disease with higher risk of upper gastrointestinal tract involvement. Those with small bowel involvement present with more extensive small bowel involvement; whereas adults frequently have small bowel disease restricted to the ileum. This may result in children being treated more aggressively early in their disease course. However, children have better overall rates of response, as drugs are targeted to decrease inflammation, with lower risk of complications such as fistulas and abscesses, derived from fibro-stenosis and penetrating disease.17,20 In a Canadian study, the risk of requiring bowel resection in a ulcerative colitis pediatric population was approximately 8% during the first year after diagnosis and increased to 29% at 10 years; these rates are significantly lower when compared to those seen in adults (Fig. 1).19

IBD does not always just affect the bowel.21,22 In a Swiss adult cohort, over one-quarter of patients presented extra intestinal manifestations (EIM), sometimes years before the diagnosis of IBD is made. This finding has important clinical implications as the development of EIM such as primary sclerosing cholangitis, uveitis and pyoderma gangrenosum can suggest that patients may develop IBD.22 Pediatricians and primary care clinicians should become familiar with the atypical presentations of IBD because 22% of children present with EIM as the only predominant initial feature.23 EIM associated with IBD in children and adolescents are erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum, peripheral and axial arthropathies, primary sclerosing cholangitis, autoimmune hepatitis, episcleritis, uveitis, and iritis.21

Treatment of IBD has evolved in the past decades and clinicians now have multiple available therapies. The medical therapy of pediatric patients is similar but not identical to adults. For instance, when inducing remission in children with CD, exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) is the first-choice due to its excellent safety profile and similar efficacy compared to corticosteroids.24 Although there is some evidence in adults, this therapy is very underused in adult mainly due to poor compliance and adherence.25,26 Anti-tumor necrosis alpha (anti-TNF) agents are recommended for children with severe disease, perianal fistulizing disease, growth failure, or extra-intestinal manifestations.13,24,27,28 Infliximab and adalimumab have shown to be effective and safe, decrease hospitalization rates and need for surgical intervention in children.29,30 Vedolizumab, a gut-selective humanized immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that antagonizes the α4β7 integrin,31 and ustekinumab, a human IgG1 kappa monoclonal antibody that targets the p40 subunit of interleukin 12 and 23,32 are approved for adult patients with moderate to severe UC and CD who had inadequate response to other therapies. There are reports in pediatric patients with clinical remission in both entities,33,34 but more data is necessary to establish safety and effectiveness and provide a recommendation. Small molecule therapy, such as tofacitinib, upadacitinib and ozanimod, has already been approved for the treatment of adults with moderate-severe UC.35–37 However, treatment in children is still off label and there is scarce evidence of concomitant use of two biologic therapies or combination of a biologic agent with tofacitinib in a refractory pediatric IBD.38

Common complications of inflammatory bowel diseases in childrenIn children, we can see unique complications such as growth impairment, delayed puberty, and psychosocial hardship.19 Growth failure has been reported in 3–10% of children with UC, being more common in males.39 Hence, it is important to monitor these patients and make sure they achieve their growth landmarks. Some patients may present with acute weight loss, while others may present with a more subtle (but chronic) failure to meet the growth landmarks at their respective age. The underlying mechanisms are still not fully understood and are probably caused by multiple factors.39,40 There is some evidence there are susceptibility genes linked to growth impairment in IBD pediatric patients, such as polymorphism in the dymeclin gene DYM,41 OCTN1/2 variants within the IBD5 Locus,42 innate dysfunction due to granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor autoantibodies (GM-CSF Ab) and concurrent CARD15 risk allele carriage.43 An additional factor that may play a role is the use of long-term steroids, which are known to affect growth and bone health. Linear growth may be affected by several mechanisms: suppression of osteoblastogenesis, favoring osteoblast and osteocyte apoptosis, and reducing bone formation. Steroids inhibit calcium absorption through the gut mucosa and favor calcium excretion in urine, as well as interfere with the GH/IGF-1 axis.39 Corticosteroids have been associated with failure to regain growth patterns. These observations support the early use of immunosuppressive and biologic therapy on those patients with marked growth impairment at onset.19,39

Delayed puberty is commonly seen in adolescents with inflammatory chronic diseases and is particularly common in females with CD. It has been described that those pro-inflammatory cytokines might inhibit the production of sex steroids through a direct action on gonads or the suppression of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) secretion. Moreover, pubertal delay may decrease bone mineralization and affect the quality of life in children who realize that their sexual maturation is different from that of their peers (Fig. 1).39

Challenges in pediatric IBD psychosocial developmentIn pediatric patients, therapeutic goals must also include the optimization of psychological growth.13,19 The impact of IBD on pediatric patients and their families has been extensively discussed in the literature. Like many other chronic diseases, IBD confers a greater risk of poor psychosocial outcomes.44 Indeed, rates of clinically significant depressive symptoms are observed in over 20% of pediatric IBD samples.45,46 A Swedish study including 6464 individuals with childhood-onset IBD reported that 17.3% of patient had been diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder. Hazard ratios were higher in the first year of follow-up but remained statistically significant after more than 5 years. These were particularly common for patients with very early-onset IBD (<6 years) and for patients with a parental history of psychiatric disease.47 As it is known, adolescence is a critical period in for mental well-being, and despite the negative implications for IBD management (e.g., nonadherence, increased disease severity, length of hospitalizations, and health care expenditures), mood disorders are often undetected and untreated.48

Another significant issue that can be seen in the pediatric IBD population are eating disorders and body image dissatisfaction. IBD patient's questionnaire reported that 13% warranted a formal evaluation for an eating disorder, and over 80% of patients responded to at least 1 question in a manner indicating a pathologic attitude toward food.49 Further, IBD is characterized by a heterogenous course and debilitating manifestations that can increase the risk for illness stigma. Studies have shown patients can experience increased concerns about impending gastrointestinal symptoms even during periods of relatively quiescent disease, further compromising their quality of life.46,50

The psychosocial well-being of both children and their families must be constantly evaluated since they often go unaddressed. Primary care physicians play a key role in identifying patients at risk and communicating finding or referring patients to mental health providers.48 Importantly, interventions should done within an interdisciplinary model, as this maximizes the possibility of early identification of emotional difficulties, timely interventions, and active parent/family involvement in treatment.46 IBD can affect school attendance, social interactions, concentration and learning. Schools and patient support networks should be aware of the implications of IBD as this may help optimize their chances of academic and social success.19

Transition of care, from pediatric to adult careCurrently, a multidisciplinary care model for the treatment of pediatric IBD and transition to adult care is considered essential. The treatment plan should actively include family members and the patient's support system prioritizing disease management, functioning across domains, and the wellbeing of children with IBD at all stages of disease. A multidisciplinary team will usually include gastroenterologists (adult and pediatric), surgeons, nurses, dieticians, psychologists, and social workers who collaboratively develop individualized and comprehensive treatment plans supporting both, child and family.51

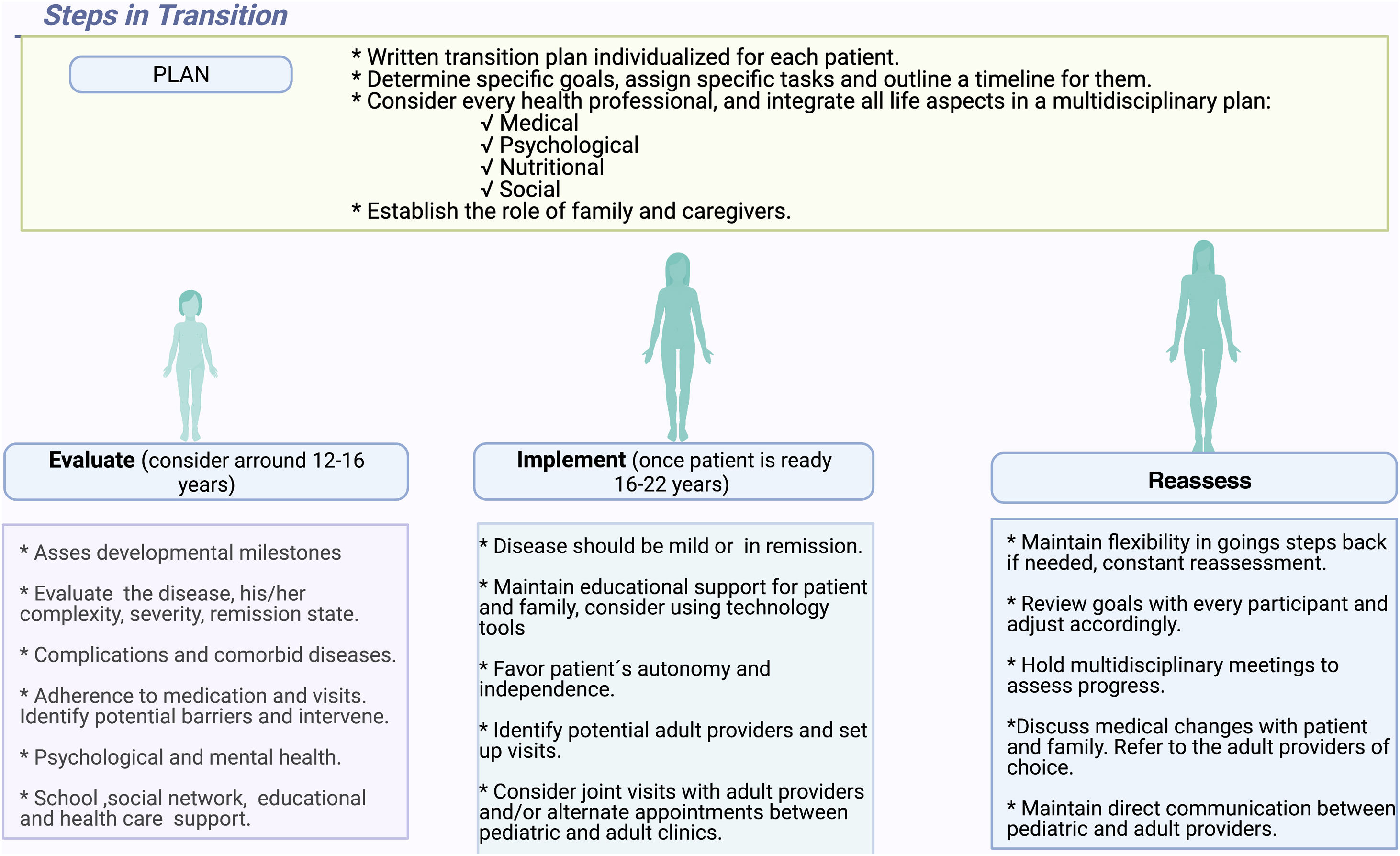

The transition of care is defined as “the purposeful and planned movement that addresses the medical, psychosocial and educational/vocational needs of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions as they move from child-centered to adult-oriented health-care systems”.52 There is still no agreement regarding the ideal transition age; suggestions range from between 16 and 22 years.53,54 That is probably related to the fact that different patients may have different needs. A recently published study showed that most pediatric gastroenterologists regarded the ideal age for transfer as being 18–22 years.55

Adolescence is a challenging stage in which most patients believe they have outgrown the childish pediatric environment and may have disputes with their medical staff and parents about the constraints caused by their condition yet fear the prospect of moving to a new hospital and seeing an unfamiliar medical team. It is not rare to see young IBD patients having less independence versus his/her peers, difficulty with relationships, social isolation, and educational and vocational challenges. Medical care may be declined during adolescence as part of the process of separation from parental control, and the youngster who loses the benefit of such parental and medical support may be more prone to risk-taking behavior such as unprotected sex, drug use and smoking.56 That is why a successful transition requires a flexible and tailored plan implemented according to the patient's developmental abilities and socio-economic environment (Table 1).

Obstacles in transition of care.

| • Abrupt transition with lack of flexibility |

| • Absence of psychological stability |

| • Reduced independence and overprotective parents |

| • Poor academic and social support |

| • Risk behaviors (sex, drugs, smoking) |

| • Scarse and untrusty relation with adult providers |

| • Non-adherence to treatment |

| • Lack of education and knowledge about the disease |

One of the big challenges to perform a successful transition from pediatric to adult care are the difference in health care models. The pediatric health care model usually takes a more family-based approach, where parents are more involved. In contrast, the adult health care model encourages patients to make independent decisions, and there are still other centers that maintain a more traditional, specialty-focused approach.57 Two challenging yet key aspects of a successful health care transition are the shift of responsibility from the caregiver to the patient and the shift of care from the pediatric provider to the adult provider.58 Parents may also be apprehensive when making changes, especially if they already have a successful and established pediatric team.56

Some questionnaires may help to identify when a patient that is seen by a pediatric team is ready to start the transition process. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) is one of the most useful tools for assessing a patient's readiness to fulfill the transition from the pediatric health service to adult care and is not disease-specific.59 TRAQ explores both the capability of self-management (e.g., handling medications, arranging for medical follow-up visits, managing finances, health insurance) and self-advocacy (e.g., communication with providers and managing activities of daily living and use of school and community resources). As far as IBD are concerned, age seems to be the best predictor of TRAQ score; lower scores on the medication management section are associated with a higher risk of nonadherence.60 Other quick questionnaires have been published to check patients’ transition readiness, such as the Got Transition,61 OSU IBD checklist,58 and the ones developed by NASPGHAN62 and by the University of Florida.63 The latter are age-adapted checklists for early, mid, and late adolescence, which can be helpful in routinely assessing patients’ readiness to initiate and guide the transition of care at the proper moment.58,63

A study including IBD pediatric patients showed that patients in transition clinics were significantly more adherent to medications and had lower rates of no shows to their appointments. They also had less of a need for surgery, and fewer hospital admissions. Additionally, a higher proportion of transitioned patients achieved their estimated maximum growth potential when completing adolescence, and there was a trend toward higher dependence on opiates and smoking on those patients that do not undergo a formal transition process.64 A recently published observational Italian pediatric-adult transition showed that there was a significant positive association between TRAQ and the Short Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (SIBDQ) scores. This study also highlights the importance of assessing readiness to transition, as this was also associated with higher HRQoL. Surprisingly, there was no difference by age, level of independence, or disease awareness.65 This suggests that transitions carried out at older ages do not necessarily improve readiness and QoL scores. In general, patients express satisfaction about the transition process, value the combined pediatric-adult visits, and appreciate having a discussion of transition well ahead of the transfer.65,66 A Pilot Multi-Site, Telehealth Hybrid Intervention that included 36 adolescents and young adults who completed a 4–5-month transition program of a group session and telehealth sessions reported overall program satisfaction. Patients perceived helpfulness and program length and format as being positive. The study showed an increase in transition readiness, self-management skill acquisition, disease knowledge, and parent-perceived transfer readiness.67 An important aspect of this study is that online interventions focused on facilitation the transitional process may also be successful when in-person visits are not possible. Furthermore, they could be used as a complement the regular in clinic visits.

The education of patients and their families is also considered a key factor when managing IBD. This not only applies to younger patients, but also adults. The patient's capacity to identify symptoms, autonomy, and knowledge about the disease and its treatment is essential to achieve optimal care. A recent review reported the benefits of including workshops and the application of web-based or text-delivered learning materials. The implementation of these programs resulted in improved disease-specific knowledge, transition competence, and medication adherence.68 Thus, technology should be considered as a potential tool to facilitate education, especially since younger patients may find it more engaging.

Studies have shown that even in late adolescence, parents seem to still play a central role in patients’ relationship with their disease, especially in managing scheduled appointments, medications and communicating with providers.65 This confirms the need to offer educational programs during childhood in order to enable patients’ independence and the capability to be self-sufficient when managing their disease. Caregivers should also encourage independent behavior in their adolescents, for example, by assigning household chores and encouraging participation in extra-curricular activities or even part-time work to further foster independence.58 A recent small cross-sectional study highlighted facilitators included having a disease narrative, deliberately shifting responsibility for disease management tasks, positivity/optimism, social support, engagement with the IBD community, and mental health support.69

Patients should transition care only when in remission. Active disease when switching from a pediatric to an adult provider has been associated with an unsuccessful transition.70 Hence, the transition of patients with active disease should be delayed until they achieve remission. This might avoid psychological hardship, promote confidence in the adult specialist, as well as improve compliance with therapy.71 A well-achieved transition results in the development of new and secure relationships for the young patient with the new health care team taking over his/her care.58

Unfortunately, most institutions do not have established transition protocols and lack the resources and training needed for a smooth transition of care. It is key to include an established strategy between pediatric and adult services, flexible timing of the transfer, a multidisciplinary team, an education program for the patient and family, a written individualized plan, and training of both pediatric and adult team members in adolescent health.51,54,58

Steps in transition should be initiated by assessing readiness. This must include evaluation of development for age, disease knowledge of the patient, and medical evaluation of disease complexity.68 Remission state, the severity of the disease, healthcare support, current medication, risk of surgical intervention, disease impact on extra-intestinal complications, and related comorbid conditions must also be considered. The next step should involve planning the transition, considering all health professionals, to achieve a multidisciplinary approach.51 The medical team, together with the patient and family, should establish goals and outline a timeline with specific tasks for each participant. Furthermore, medical records must properly document the patient's medical history. These records should be readily available to the team taking over the care. The current therapeutic landscape in IBD includes multiple agents and treatment strategies (e.g. therapeutic drug monitoring) and all the medical information can be valuable and may avoid repeating testing.54 Only when the decision to transition the patient is made, the medical team can proceed. The next step involves the implementation of a transition plan. During this time, the patient must demonstrate some degree of autonomy and be able to schedule visits, take his/her treatments, follow an adequate diet and be able not only to follow recommendations, but also to be able to reach out with questions and/or concerns. Ideally, the patient should be able to attend clinic visits independently. Providers must constantly reassess the success of the transition progress, identifying and addressing potential barriers.58 Patients are considered eligible for adult care when most of the transition readiness skills have been mastered; the patient ought to appropriately identify and communicate when they have symptoms, have a correct insight of the disease itself, know when to request medical attention, and have a good family and social support network. To progress, the underlying disease must be mild or quiescent, with a low risk of short-term surgical intervention.71 The final step must involve all multidisciplinary participants who should review goals and adjust accordingly. Pediatric providers must place referrals to adult providers in all disciplines and ideally directly sign-off each patient. This is a pivotal phase of the transition of care. In an ideal scenario, a first encounter with the adult physician should include the pediatric gastroenterologist. Alternating between the adult and pediatric provider is also a viable alternative and should be considered.54 It is also important to maintain an open channel of communication between providers until the patient has fully transferred (Fig. 2).

ConclusionsThe overall prevalence of IBD has substantially increased, although data on the pediatric population is scarce. Caring for pediatric patients can present unique challenges as they may develop distinctive complications associated to IBD such as failure to thrive, delayed puberty and psychosocial hardship. With all of this in mind, therapeutic strategies may vary, and management should always involve a multidisciplinary team. Most institutions that manage IBD patients do not have a formal transition policy, which can negatively affect patient care. A transition plan should be explicit, clear and tailored to each patient. A successful process may improve patients’ adherence to medication and visits and can also improve their disease-specific knowledge and self-management. These improvements may translate into fewer disease-related emergency department visits and reduce hospitalization rates leading to less frequent need for therapy escalation. Given that the transition from the pediatric to the adult care system is a crucial phase in the management of any chronic disease, all institutions that manage pediatric IBD should have a well-established and clear transition protocol.

Authors’ contributionsAll authors equally contributed equally to this review with the conception and design of the study, literature review and analysis, drafting, critical revision and editing, and the approval of the final version.

FundingNo funding to declare.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.