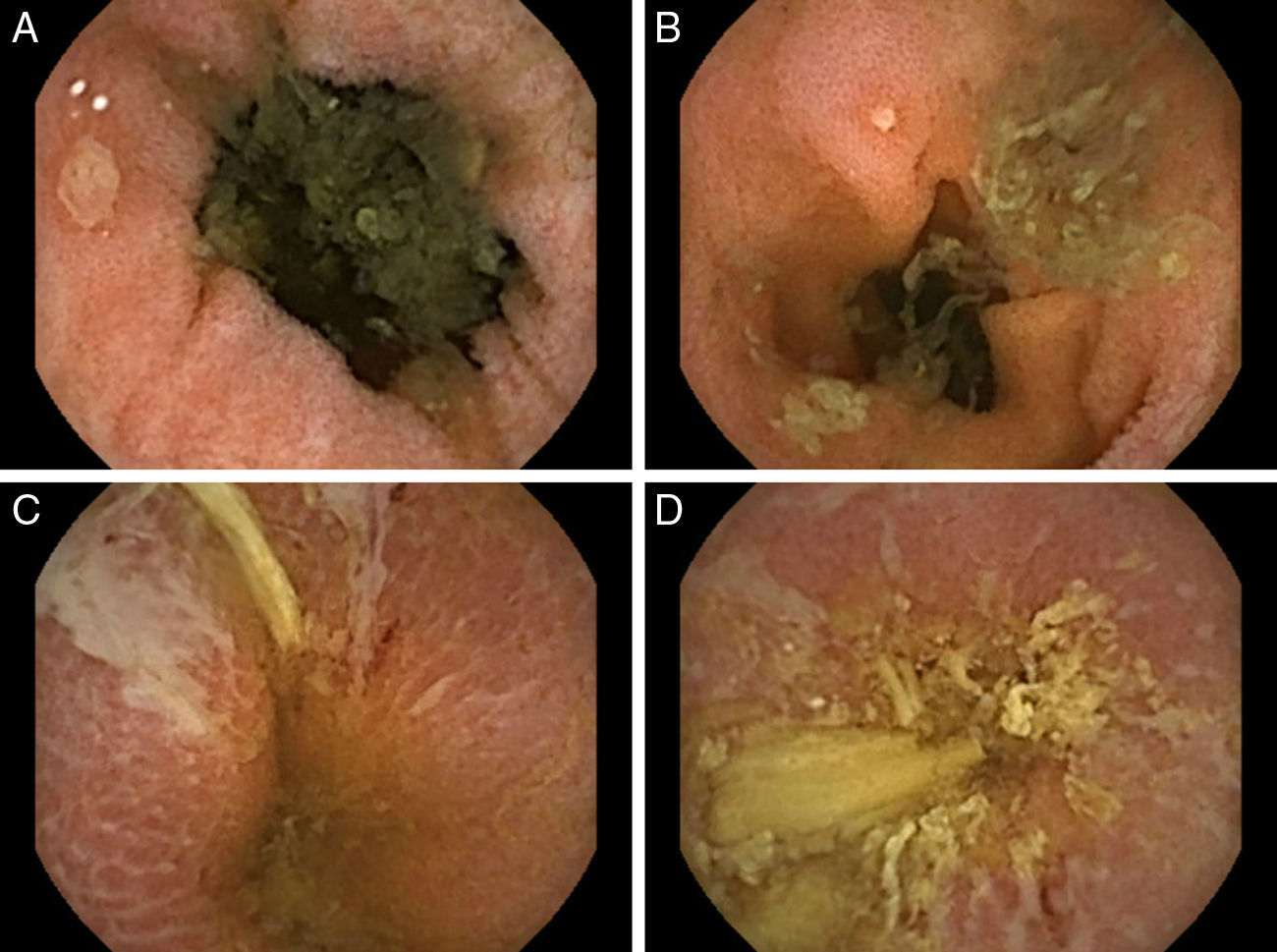

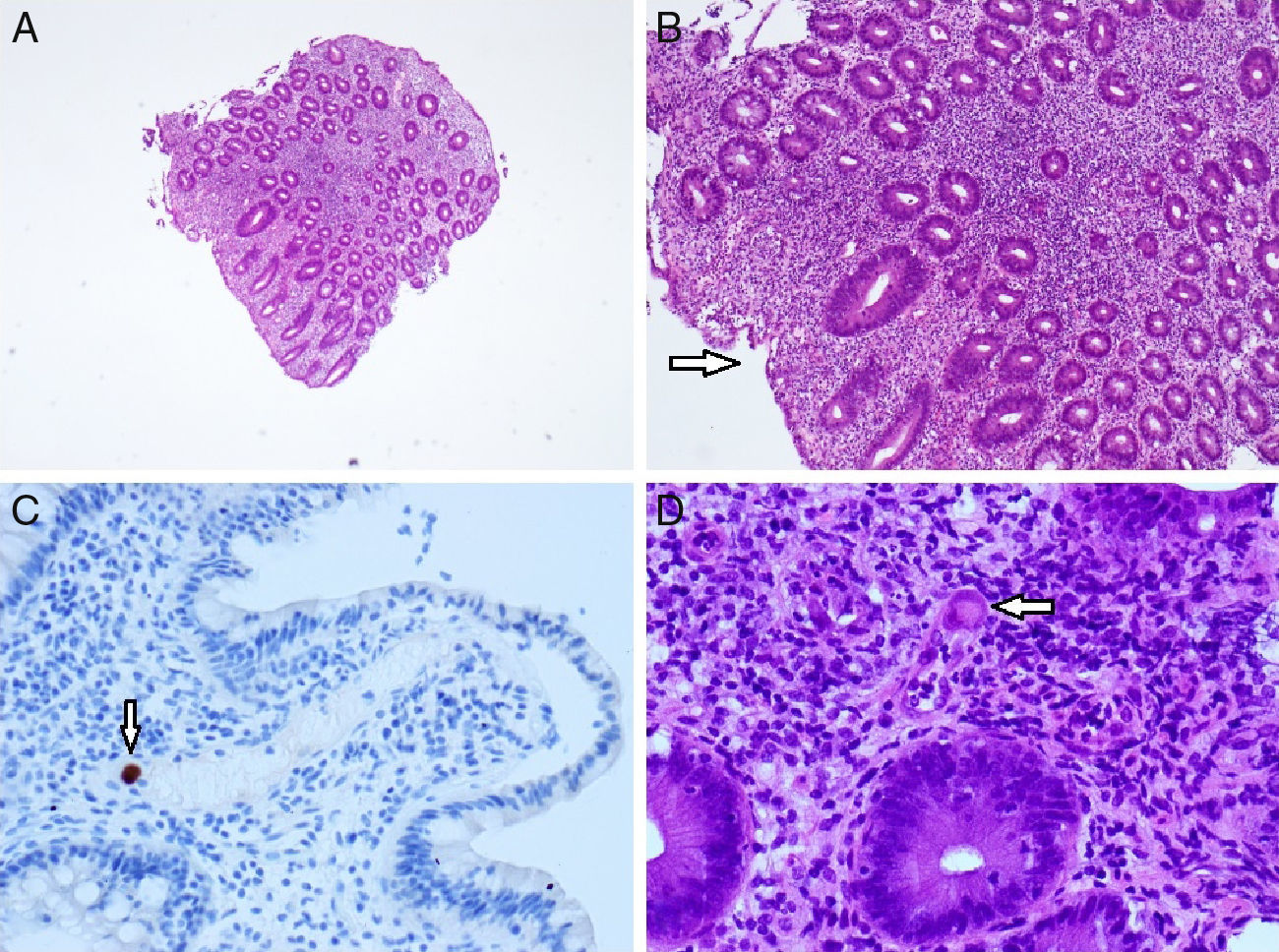

Common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) is an antibody deficiency with a high variability in its clinical presentation. It is estimated to affect as many as 1 in 25,000 individuals.1 According to the largest European database (including 902 patients),2 the most common reported disorders were pneumonia (32%), autoimmunity (29%), splenomegaly (26%) and bronchiectasis (23%). The main features include respiratory tract infections and their associated complications, enteropathy, autoimmunity and lymphoproliferative disorders. Gastrointestinal disease is deemed to occur in 15% of the patients and despite clinical immunodeficiency, opportunistic infections are not a typical manifestation of CVID. The authors report a case of a 69-year-old Caucasian female with a previous diagnosis of CVID since 2002 (receiving intravenous Ig [immunoglobulin] on a three-week basis) and a non-specific interstitial pneumonitis (under systemic steroids – prednisolone 20mg per day). She was admitted in our department with a chronic and severe watery diarrhea (8–10 bowel movements per day) lasting for 8 weeks and weight loss (7kg in 8 weeks). At presentation, she denied fever, abdominal pain, visible blood or pus in the feces, recent travels or new drugs (namely nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). Upon physical examination, the patient was pale and dehydrated but afebrile and hemodynamically stable. A mild peripheral edema was noted. Labs demonstrated a marked increase in inflammatory parameters (leucocytosis [19,900×106cel/mm3] with neutrofilia [91%], trombocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein [7.1mg/dL] and erythrocyte sedimentation rate [38mm/h), severe hypokaliemia (2.6mmol/L), hypomagnesiemia (1.5mg/dL) and hypoalbuminemia (2.4mg/dL). Stool examinations for bacteria, Clostridium difficile, ova, cysts and parasites were negative. Cryptococcus and Giardia lamblia antigen and cultures were persistently negative. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C virus serologies were negative. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) serology was positive for IgG and negative for IgM. Upper endoscopy did not demonstrate any findings; however, biopsies taken from the duodenum revealed a mild villous atrophy and a chronically active duodenitis. Ileocolonoscopy observed in the right colon a continuous area of hyperemia and erythema without obvious ulceration (biopsies were performed). The observed mucosa of the terminal ileum was normal. Upon the absence of categorical findings for the chronic diarrhea, a capsule endoscopy was performed (Fig. 1). Starting at the distal part of the jejunum, multiple small and rounded ulcers were observed (Fig. 1A and B). More distally, linear and serpiginous ulcers were also observed (Fig. 1C and D). Later, biopsies taken from the right colon revealed the presence of multiple CMV inclusions (confirmed with immunohistochemistry; Fig. 2C) and small vessels vasculitis (Fig. 2D). In a patient with a chronic severe diarrhea with marked increase of inflammatory markers, the mentioned small-bowel findings and the anatomo-pathological findings from the right colon, a presumptive diagnosis of CMV enterocolitis was assumed and intravenous ganciclovir was promptly initiated. Oral steroids were reduced by half the dose. After 4 weeks of antiviral therapy, the patient was discharged, she had two bowel movements per day and her electrolytic imbalance was controlled.

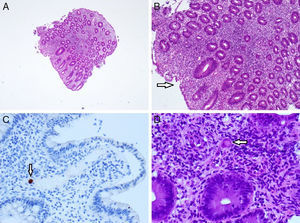

Histologic findings (right colon). Hematoxylin and eosin staining 4× and 10× magnification (A and B): marked inflammatory changes and an area of superficial ulceration (arrow). CMV immunostaining (C): immunohistochemically stained biopsy specimen showing a cytomegalovirus-positive cell (arrow); hematoxylin and eosin staining 40× magnification (D): small vessel vasculitis by a giant cell with inclusion body characteristic of CMV (arrow).

The main gastrointestinal symptom in CVID is a transient or persistent diarrhea,3,4 mostly due to Giardia lamblia persistent infection, norovirus, Campylobacter jejuni or Salmonella. Even thought, many gastrointestinal symptoms cannot be imputed to an infectious etiology. Inflammatory bowel disease remains an important differential diagnosis to be made, being present in 19–32% of those with persistent severe diarrhea, steatorrhea and malabsorption.1 In fact, gastrointestinal disease in CVID displays so many features that can mimic lymphocytic and collagenous colitis, lymphocytic gastritis, celiac disease, granulomatous disease, acute graft-versus-host disease and inflammatory bowel diseases.3 The standard of care in CVID is replacement Ig (300mg/kg every 3 weeks or 600mg/kg per month). This therapy greatly impacts on bacterial infections incidence.5 However, it does not appear to have significant impact on other inflammatory complications like progressive lung disease, gastrointestinal and granulomatous disease, autoimmunity, lymphoid hyperplasia and lymphoma. Additionally to the most obvious risk factor (CVID) in our patient, we admit that despite following regular Ig administrations, long-term oral steroids have played an important role in this opportunistic gastrointestinal infection. CMV infection and disease is relatively common among HIV infected patients and among those with secondary immunosuppression (e.g., post-transplant). Albeit that, severe organ damage, even on those patients, is considered rare. Clinically, small-bowel involvement (due to infection of vascular endothelial cells) may range from mild anorexia to overt massive gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation.6,7 Capsule endoscopy (CE) is widely accepted for small-bowel investigation. Its diagnostic yield in chronic diarrhea is considered to be low, ranging from 13 to 24%8,9; however, in the present case, this technology enabled us to establish the diagnosis of CMV enterocolitis without histological sampling of the small-bowel. Clinical, laboratorial and endoscopic resolution after proper antiviral treatment finally supported the initial diagnosis. In conclusion, this case illustrates the difficult diagnosis of CMV enteritis in an immunocompromised patient, only made possible after conserted endoscopic and pathological assessment.