We present the case of a 52-year-old patient with a 26-year personal medical history of chronic hepatitis C (HCV) infection. The patient was diagnosed with kidney failure secondary to non-proliferative glomerulonephritis and underwent a kidney transplant in 1991 with delayed graft failure in 2007, since which point he has been on haemodialysis. He has subsequently undergone surgery on three separate occasions due to iliac artery aneurysm and mitral valve disease, complicated by endocarditis in 2011, which is being treated with acenocoumarol.

He has been attending the gastrointestinal outpatient clinic since 2009. The patient is infected with genotype 1b and a liver biopsy revealed stage 3/6 fibrosis. Monotherapy was started with pegylated interferon (IFN) alpha-2a 135μg/week, obtaining a biochemical and virological response throughout the 48 weeks of treatment, with recurrence 6 months after treatment was withdrawn.

Triple therapy was first contemplated in 2012. The degree of fibrosis was staged by elastography, which revealed 16.6kPa (corresponding to F4 on the METAVIR score), and the IL28B polymorphism was identified as the CC genotype.

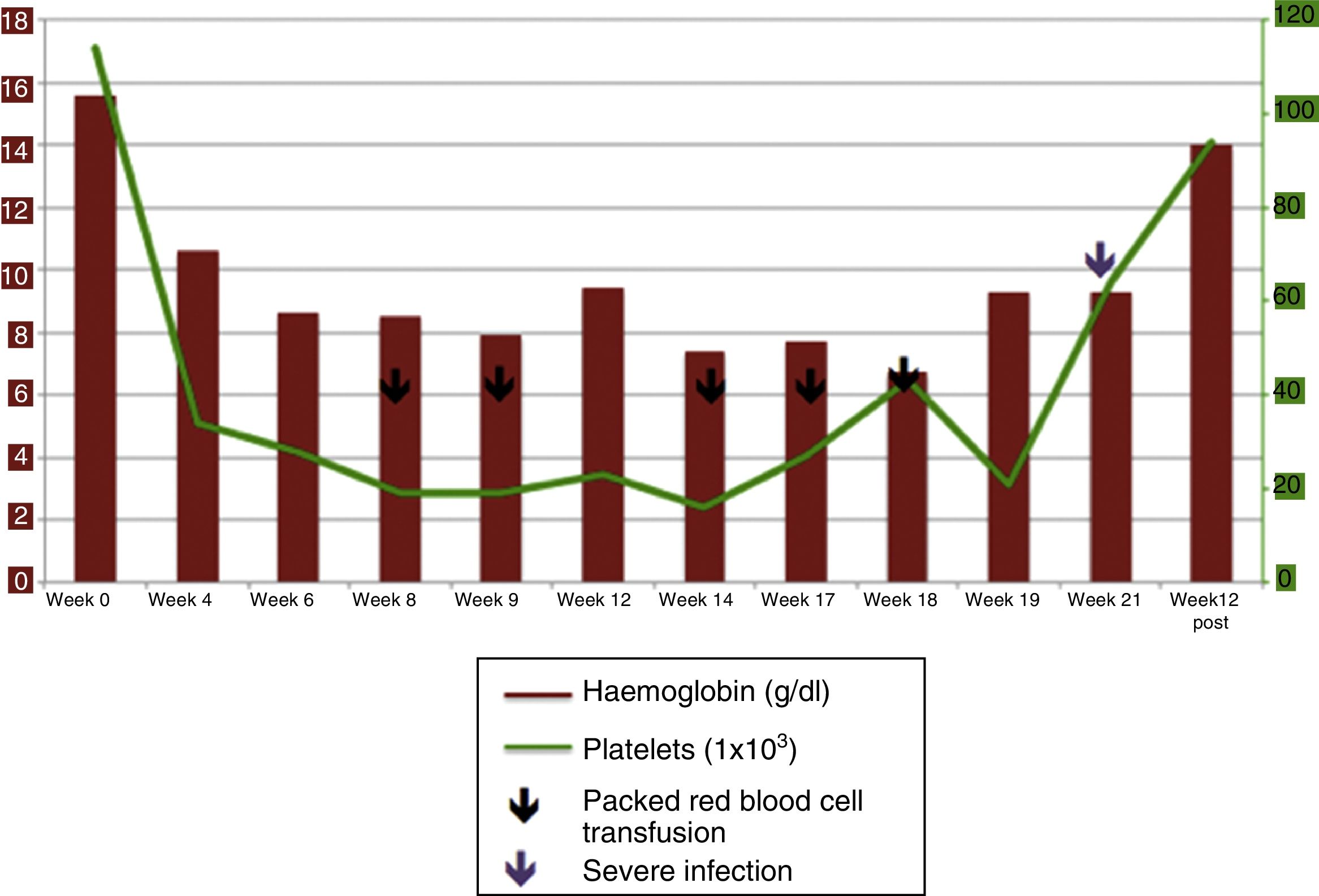

Triple therapy with telaprevir was started in February 2014 with the dose adjusted due to kidney failure: IFN 135μg/week, ribavirin (RBV) 200mg/day and telaprevir 750mg/8h. The lab tests at the start of treatment revealed thrombocytopaenia of 114×103/l, GPT 67 and creatinine of 10.7mg/dl. The complete blood count conducted in week 4 showed a 5g/dl fall in haemoglobin (Hb) levels (previous Hb level 15.6g/dl), together with normal transaminase levels and a viral load (VL) <15IU/ml.

Two packed red blood cell units and two platelet units were required for the first time in week 8 following a fall in Hb levels to 8.6g/dl and thrombocytopaenia of 18×103/l, which led to IFN administration being postponed for one week (Fig. 1). The patient had an undetectable viral load at 12 weeks. Four further packed red blood cell units were transfused in the following weeks due to new episodes of anaemia (with Hb levels falling to 6.7g/dl), and RBV was finally withdrawn in week 18.

Five months after initiating treatment, the patient was admitted with Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia caused by the tunnelled haemodialysis catheter, with resolution of symptoms upon changing the catheter and administering intravenous antibiotics. Given the patient's clinical status, antiviral treatment was permanently withdrawn in week 21.

In the 3- and 6-month post-treatment follow-ups, the patient's blood levels had completely recovered, with normal Hb levels, an undetectable viral load and sustained viral response that the patient maintained.

The prevalence of chronic HCV infection is higher in patients with chronic kidney disease than in the general population. It currently stands at 5.6% in Spain, and prevalence increases as the number of years on haemodialysis increases.1 As such, the Spanish Society of Nephrology recommends anti-HCV screening in these patients.2

The survival of haemodialysis patients is compromised by HCV,3,4 which represents the fourth-highest cause of mortality and the main cause of post-kidney transplantation liver dysfunction due to the earlier onset of cirrhosis and the greater risk of liver cancer.3,5,6

Use of antiviral treatment in dialysis patients has been limited due to the adverse effects of IFN and RBV-induced haemolytic anaemia.7,8

Over time, the use of pegylated alpha interferon, either alone or in combination with RBV, has shown low sustained virological response (SVR) rates and significant pharmacological intolerance, despite adjusting the dose in accordance with the glomerular filtration rate.4,8 Improved SVR rates have been achieved with the use of direct-acting protease inhibitors in combination with IFN or RBV (around 70% at 48 weeks), without having to adjust the protease inhibitor dose as it is not primarily excreted by the kidneys.9,10 However, it should be noted that severe adverse effects hinder its use.

In our case, the side effects (anaemia and thrombocytopaenia associated with sepsis) ultimately led to suspension of the treatment in week 21.

Despite advances having been made over the last 2 years with the introduction of triple therapy, the objective is to find IFN-free treatments with minimal side effects.7 Numerous studies are currently ongoing to evaluate the response rates of such treatments in patients with kidney failure. With the exception of sofosbuvir, which would not have been indicated in this case owing to a creatinine clearance of less than 30ml/min, the combination of ombitasvir/paritaprevir/ritonavir/dasabuvir would have been an appropriate treatment option as these drugs are not primarily eliminated by the kidneys, although they were not available at the time of treating our patient. Equally, elbasvir/grazoprevir, which are due to be released soon, would be a good option for this type of patient.

Please cite this article as: Plana L, Peño L, Urquijo JJ, Diago M. Difícil manejo del tratamiento con triple terapia en paciente con hepatitis crónica C y hemodiálisis. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:356–358.