Vibrio cholerae (V. cholerae) is a Gram-negative, curved, mobile, oxidase- and catalase-positive, facultative anaerobe bacillus commonly found in marine environments.1 More than 200 different serogroups have been identified based on the nature of the lipopolysaccharide O-antigen of its wall, and epidemic cholera is caused by the O1 and O139 serogroups.1 The non-toxigenic serogroups (non-O1 and non-O139) tend to be linked to the onset of self-limiting gastroenteritis after seafood consumption, particularly bivalve filter-feeding molluscs, with symptoms potentially as severe as cholera.2,3 Notwithstanding its potential involvement in otitis externa, cellulitis and wound infection, the enteroinvasive potential of the non-toxigenic serogroups is limited and only affects hosts with particular comorbidities.4

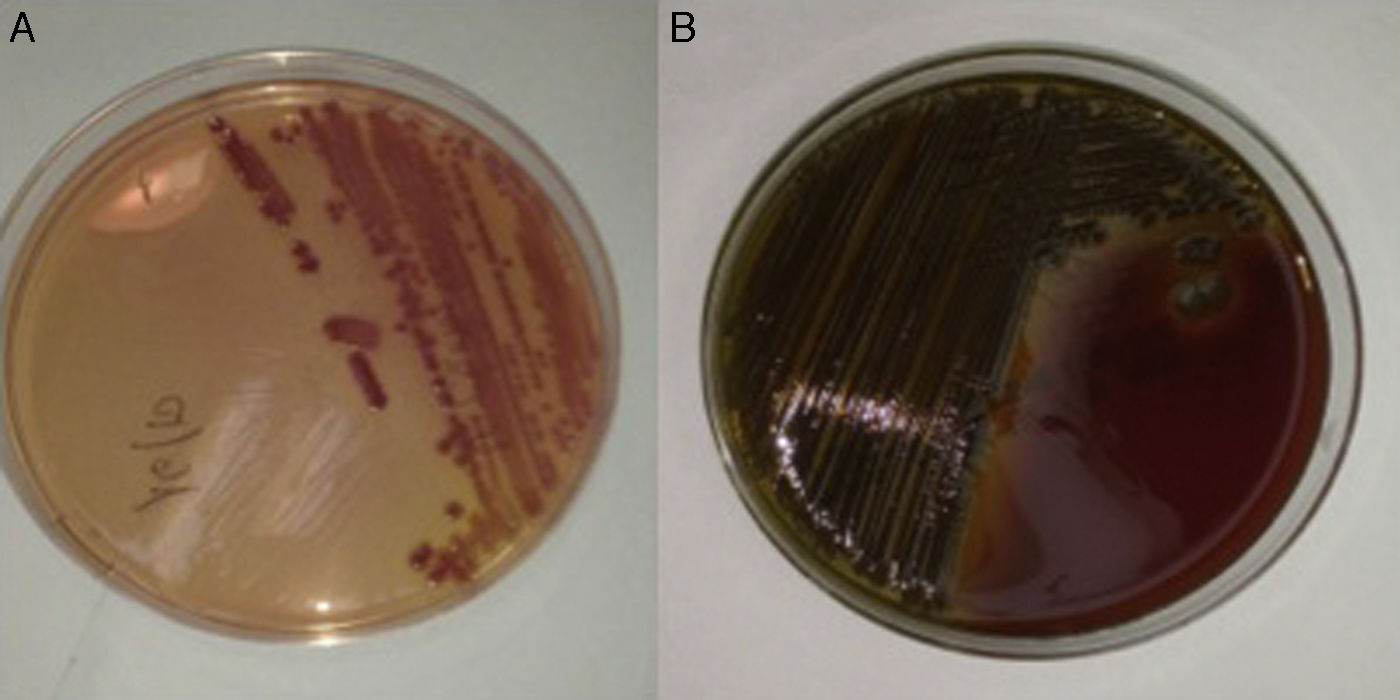

We present the case of a 56-year-old male patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus and alcoholic liver cirrhosis with a Child-Turcotte-Pugh class of A6 (9 points on the MELD score), who had developed ascitic and oedematous compensation, oesophageal and gastric varices and thrombosis of the splenoportal venous axis as prior complications. The patient was taking spironolactone, furosemide, propranolol, tinzaparin and insulin glargine. He attended A&E having experienced the onset, 24h previously, of dysthermia with a temperature measured at home of 38.5°C, drowsiness, odynophagia and cough without expectoration, as well as loose bowel movements. The physical examination revealed an axillary temperature of 36.8°C (after taking an antipyretic), blood pressure of 113/59mmHg, a heart rate of 87bpm and clinical signs of chronic liver disease. The lab tests revealed thrombocytopaenia (26.0×109platelets/l), increased acute phase reactants (C-reactive protein 14.9mg/dl; normal range: 0.1–0.5), hypertransaminasaemia (gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase [GGT] 114IU/l, alkaline phosphatase 134IU/l) and mildly impaired liver function tests (total bilirubin 2.7mg/dl, INR 1.29). The white blood cell count was normal (4.7×109leukocytes/l). An abdominal ultrasound only found a minimal number of ascites barely consistent with underlying chronic liver disease, while the chest X-ray revealed no consolidations. Assuming a possible diagnosis of respiratory tract infection, empirical treatment was started with levofloxacin (500mg every 24h) and the patient was discharged after obtaining two sets of blood cultures (BacT/ALERT® 3D system, bioMérieux, Marcy l’Etoile, France). After 24h, a curved, lactose-and oxidase-positive Gram-negative bacillus was isolated in the MacConkey agar plate of one of the sets, which formed greenish colonies in the blood agar plate (Fig. 1). Using biochemical testing (MicroScan WalkAway® system, Siemens, California, USA), mass spectrometry (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany) and direct agglutination (BD Difco Vibrio cholerae Antisera, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD, USA), non-toxigenic V. cholerae was identified. The antibiogram confirmed susceptibility to aminopenicillins and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole. At that time the patient was asymptomatic and afebrile, so it was decided to maintain treatment with levofloxacin for 10 days. Upon questioning, the patient mentioned having eaten a large amount of shellfish a few days prior to symptom onset, including razor clams (Ensis spp.), steamed cockles (Cerastoderma edule) and mussels (Mytilus galloprovincialis), as well as grilled shrimp (Aristaeopsis edwardsiana). His partner, who had also eaten this seafood, coincidentally experienced mild gastroenteritis.

Although the clinical significance and public health impact of the non-toxigenic serogroups of V. cholerae (also known as non-agglutinating or non-choleric) was questioned for a long time, its involvement in outbreaks of diarrhoea in immunocompetent subjects after the consumption of contaminated seafood has been documented in several European countries.2 A recent study demonstrated an elevated prevalence of non-toxigenic V. cholerae in prawns (17%) and mussels (9%) harvested off the Italian coast.5 Given that it requires a temperate saline aquatic environment for optimal growth (>15°C), it has been suggested that rising average sea temperatures as a result of global warming could explain the increased incidence of V. cholerae infection, including at more northern latitudes.2,5

The pathogenicity of non-toxigenic V. cholerae may be increasing due to the presence of a wide spectrum of virulence factors, including extracellular enzymes, enterotoxins and haemolysins.5,6 As a result of iron overload and inhibited opsonophagocytosis and reticuloendothelial clearance (which favour bacterial translocation from the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract), liver cirrhosis is one of the most common comorbidities associated with the onset of enteroinvasive V. cholerae infections.4,7 Examples of bacteraemia, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and endophthalmitis can be found in the literature.4,6–9 Many of these cases arise in South-east Asia7–9 and have only been reported anecdotally in Spain.10 The mortality rate of bacteraemia episodes is believed to be around 47%.4 Most non-toxigenic V. cholerae isolates are susceptible to third-generation cephalosporins, tetracyclines, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and fluoroquinolones.2,7,8 Thanks to their in vitro bactericidal action and good oral bioavailability, fluoroquinolones represent an excellent therapeutic option, as our case study shows.

In conclusion, it is hoped that the non-toxigenic V. cholerae serogroups will be considered in the future as an emerging cause of gastrointestinal infection in our setting. Cirrhotic patients are particularly susceptible to bacteraemia and other forms of enteroinvasive infection, which may be associated with significant mortality. This should be taken into account in order to effectively question the patient about their recent eating habits and to potentially administer empirical antibiotic therapy should suggestive symptoms present. Finally, patients with cirrhosis should be warned of the risks that could arise from consuming raw or semi-raw seafood.

FundingMario Fernández Ruiz benefits from a Juan Rodés clinical research agreement (JR14/00036) from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest with regards to this article.

Please cite this article as: Fernández-Ruiz M, Carretero O, Orellana MÁ. Bacteriemia por Vibrio cholerae no toxigénico: los riesgos del consumo de marisco en un paciente cirrótico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:358–360.