Nephrotoxicity has been described in some patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) treated with 5-aminosalicylates (5-ASA). Our aim was to conduct a retrospective study of IBD patients, both with and without 5-ASA treatment, who underwent regular evaluation of renal function over a 4-year period.

MethodsSerum creatinine was measured before the start of 5-ASA therapy, and thereafter yearly up to 4 years. Creatinine clearance (ClCr) was estimated from serum creatinine (Cockroft & Gault formula). The influence of 5-ASA treatment on renal function was assessed by univariate and multivariate analysis.

ResultsA total of 150 IBD patients (ulcerative colitis in 45%, Crohn's disease in 55%) were included. Sixty-two patients were receiving 5-ASAs (95% coated mesalazine, mean dose 1.9±0.8g/day). Both serum creatinine levels and ClCr were similar in patients with and without 5-ASA treatment, and remained stable throughout the 4-year follow-up in patients taking 5-ASAs. In the multivariate analysis, 5-ASA treatment (or its dose) was not correlated with serum creatinine levels or ClCr. No interstitial nephritis was reported during follow-up.

Conclusion5-ASA-related renal disease was not found in our series, suggesting that the occurrence of renal impairment in IBD patients receiving these drugs is exceptional. Our results do not support the recommendation of serum creatinine monitoring in patients receiving 5-ASA treatment.

Se han descrito algunos casos de nefrotoxicidad en pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) tratados con 5-aminosalicilatos (5-ASA). Nuestro objetivo fue realizar un estudio retrospectivo de un grupo de pacientes con EII, con y sin tratamiento con 5-ASA, en los que se evaluaba la función renal regularmente durante un período de 4 años.

MétodosSe determinaba la creatinina sérica antes de comenzar el tratamiento con 5-ASA y posteriormente se efectuaba un control analítico anual durante 4 años. Se estimó el aclaramiento de creatinina (ClCr) a partir de la creatinina sérica (fórmula de Cockroft-Gault). La influencia del tratamiento con 5-ASA en la función renal se valoró mediante análisis multivariante.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 150 pacientes con EII (un 45% con colitis ulcerosa y un 55% con enfermedad de Crohn). Los valores séricos de creatinina a los 0, 1, 2, 3 y 4 años en los pacientes que recibían 5-ASA permanecieron estables. Asimismo, el ClCr no se modificó durante los 4 años de seguimiento en los pacientes tratados con 5-ASA. Más aún, los valores tanto de creatinina sérica como de ClCr fueron similares en los pacientes con y sin tratamiento con 5-ASA. Finalmente, el tratamiento con 5-ASA no se correlacionó con los valores séricos de creatinina ni con el ClCr en el estudio multivariante. No se describió ningún caso de nefritis intersticial durante el seguimiento.

ConclusiónNo hemos constatado ningún caso de nefrotoxicidad en nuestra serie de pacientes tratados con 5-ASA, lo que indica que la incidencia de alteraciones de la función renal en los pacientes con EII que reciben estos fármacos es excepcional. Nuestros resultados no apoyan la recomendación de registrar regularmente las cifras de creatinina sérica en los pacientes con EII que reciben tratamiento con 5-ASA.

In mild to moderate active ulcerative colitis, both sulfasalazine and 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) have proven efficacy in inducing and maintaining clinical remission1,2. Considerations of long-term toxicity are important as lifetime maintenance treatment is usually recommended for ulcerative colitis. The introduction of 5-ASA into the treatment of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has offered the opportunity of increasing dosages much further than had been possible with sulphonamide carrier compounds such as sulfasalazine, as a major advantage of 5-ASA agents is the safety profile2. However, a number of cases have been reported with 5-ASA-related toxicity3,4. In particular, nephrotoxicity, which may be potentially irreversible, has been described in some patients with IBD treated with 5- ASA3-5. In this respect, both acetylsalicylic acid and phenacetin, which have been implicated in the occurrence of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug induced nephropathy, share structural similarities with 5-ASA6,7. Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that 5-ASA may cause lesions to kidney tubular epithelial cells in animals when fed in high doses6,7.

The actual incidence of nephrotoxicity in IBD patients receiving 5-ASA therapy has not been determined, but it has been suggested that renal impairment may occur in up to 1 in 100 patients treated with 5-ASA, although clinically important interstitial nephritis would occur in only 1 in 500 patients8. However, data regarding potential of renal impairment by 5-ASA therapy are contradictory, with some studies reporting an incidence > 1% of interstitial nephritis, and others suggesting that 5-ASA treatment has no effect on renal function5. Nevertheless, these data are based on a relatively low number of patients and with a limited follow-up.

Consequently, despite increasing recognition of the potential for this serious adverse event (nephrotoxicity), guidelines for monitoring renal function in patients prescribed 5-ASA preparations are not widely employed3. Furthermore, no evidence exists to date that either the test, or the frequency of testing, is effective in identifying these patients at risk of developing 5-ASA-related renal impairment, and therefore there are no firm recommendations for renal function monitoring in IBD patients treated with these drugs.

Our aim was to conduct a retrospective study of IBD patients, both with and without 5-ASA treatment, evaluating parameters of renal function regularly analyzed during 4 years, to assess whether long-term use of these drugs has detrimental effects on renal function.

PATIENTS AND METHODSPatient populationConsecutive patients with the diagnosis of IBD at the Gastroenterology Unit from the Hospital Universitario de la Princesa (Madrid, Spain) and followed-up for at least 4 years, were included in this retrospective study. Diagnoses of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis were established by standard clinical, radiological, histological, and endoscopic criteria9. The Vienna classification of Crohn’s disease based on Age at Diagnosis –under 40 years (A1), equal to or over 40 years (A2)], Location [terminal ileum (L1), colon (L2), ileocolon (L3), upper gastrointestinal (L4)], and Behaviour [nonstricturing nonpenetrating (B1), stricturing (B2), penetrating (B3)–, was used. For ulcerative colitis, a classification based on the location and extension of the disease was used: proctitis, left-side colitis (up to the splenic flexure), and extensive colitis/pancolitis. Exclusion criteria were: pre-existing renal disease, cardiac or hepatic failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, patients treated with diuretics or antihypertensive drugs, and the history of chronic ingestion of aspirin or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Data collectionMedical records from these patients were reviewed for the study. At baseline, the following variables were prospectively extracted in a predefined data extraction form: age, sex, smoking habit, body weight, type of IBD, site of involvement, history of bowel resections, and use of medication since the diagnosis (mainly with 5-ASA, but also with other drugs used for the treatment of IBD, and with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs). With respect to the use of 5-ASAs, patients were divided into the following subgroups: patients without a history of 5-ASA treatment, with a history of sulfasalazine, with a history of mesalazine, or with a history of both compounds. 5-ASA dosage was categorized as: low (less than 1.5 g/day), intermediate (more than 1.5 but less than 3 g/day) and high (more than 3 g/day). All data obtained were collected in an anonymous database for the analysis, which was approved by the local Medical Ethical Committee.

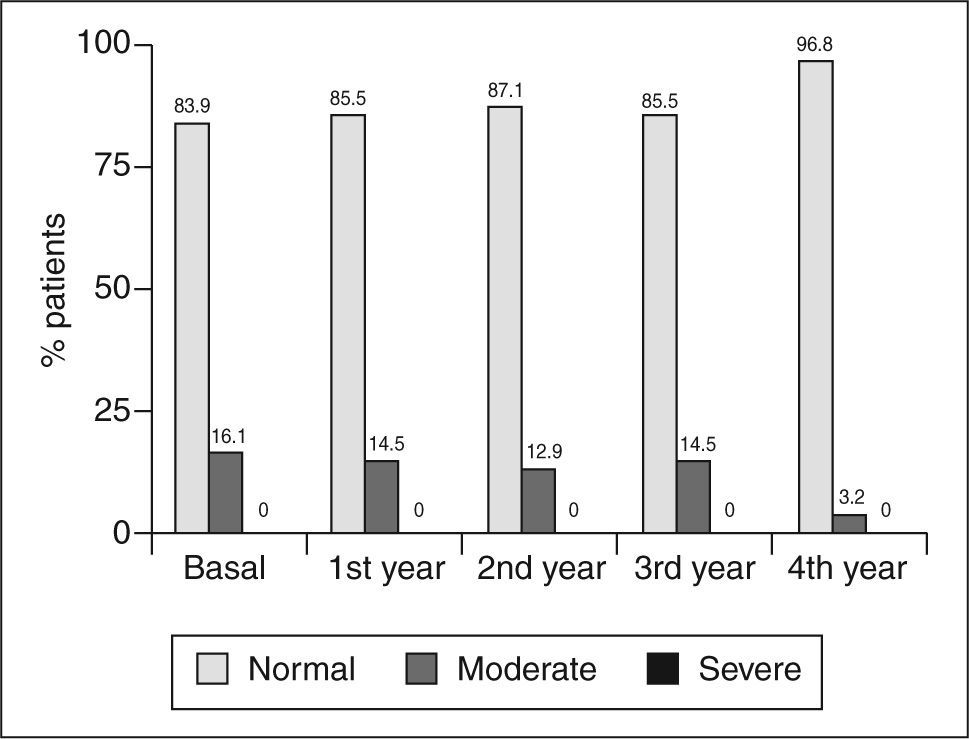

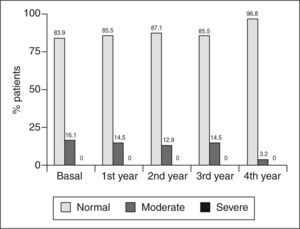

Assessment of renal functionPatients were reviewed in our out-patient clinic every 6 months for clinical evaluation of disease activity. Analytical controls (including complete blood count and biochemistry including creatinine) were performed every 12 months in all patients. Renal function was monitored by measuring levels of serum creatinine in all patients (both with and without 5-ASA treatment). In patients taking 5-ASAs, serum creatinine was measured before starting 5-ASA therapy, and thereafter yearly up to 4 years (patients were taking the drug at a stable dose for the 4-year period of study). Because creatinine excretion was not regularly measured, we were unable to calculate endogenous creatinine clearance (ClCr). Therefore, ClCr was estimated from serum creatinine with the Cockroft and Gault formula, which takes into account age, weight and sex10,11. The ClCr (in ml/min) was calculated by the following formula: (140 – age [in years] × body weight [in kg]/72 × serum creatinine [in mg/100 ml]); because of differences in body composition, a correction factor of 0.85 was used for women. Based on the estimated glomerular filtration rate, patients were classified as having: normal renal function (ClCr > 60 ml/min), moderate impairment (ClCr 30-59), severe impairment (ClCr 15- 29), and advanced renal failure (ClCr < 15)11.

Statistical analysisFor continuous variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated. For categorical variables, percentages and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were provided. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test, and quantitative variables with the Student t test. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The influence of 5-ASA treatment on renal function was assessed by multivariate analysis (multiple linear regression analysis). The dependent variable was ClCr, and the independent variables were: age (categorized as higher or lower than 42 years, which was the median value), sex (male/female), smoking (smokers/non-smokers), weight (categorized as higher or lower than 67 kg, which was the median value), type of IBD (ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease), and treatment with 5-ASAs or steroids.

RESULTSOne-hundred and fifty patients (45% with ulcerative colitis and 55% with Crohn’s disease) were included in the study. Mean age was 45 ± 15 years, 45% were males, and 30% were smokers. Vienna classification of Crohn’s disease patients was as follows: age at diagnosis (A1, 79%; A2, 21%), location (L1, 25%; L2, 20%; L3, 51%; and L4, 4%), and behaviour (B1, 43%; B2, 21%; and B3, 36%). Ulcerative colitis location distribution was as follows: proctitis (25%), left-side colitis (43%), and extensive colitis/ pancolitis (32%).

Sixty-two patients (46 with ulcerative colitis, 16 with Crohn’s disease) were receiving 5-ASA treatment: 59 patients (95%) received coated mesalazine (Claversal® or Lixacol®), 1 patient (1.6%) received prolonged release mesalazine (Pentasa®), and 2 patients (3.2%) received sulfasalazine. Mean dose of mesalazine was 1.9 ± 0.8 g/day (range, 0.5-4), and most patients were receiving between 1 and 3 g/day (< 1 g/day, 4 patients; 1-2 g/day, 21 patients; 2-3 g, 22 patients; and 3-4 g/day, 8 patients). Sixty-three patients were receiving azathioprine or mercaptopurine, and 3 patients were treated with infliximab.

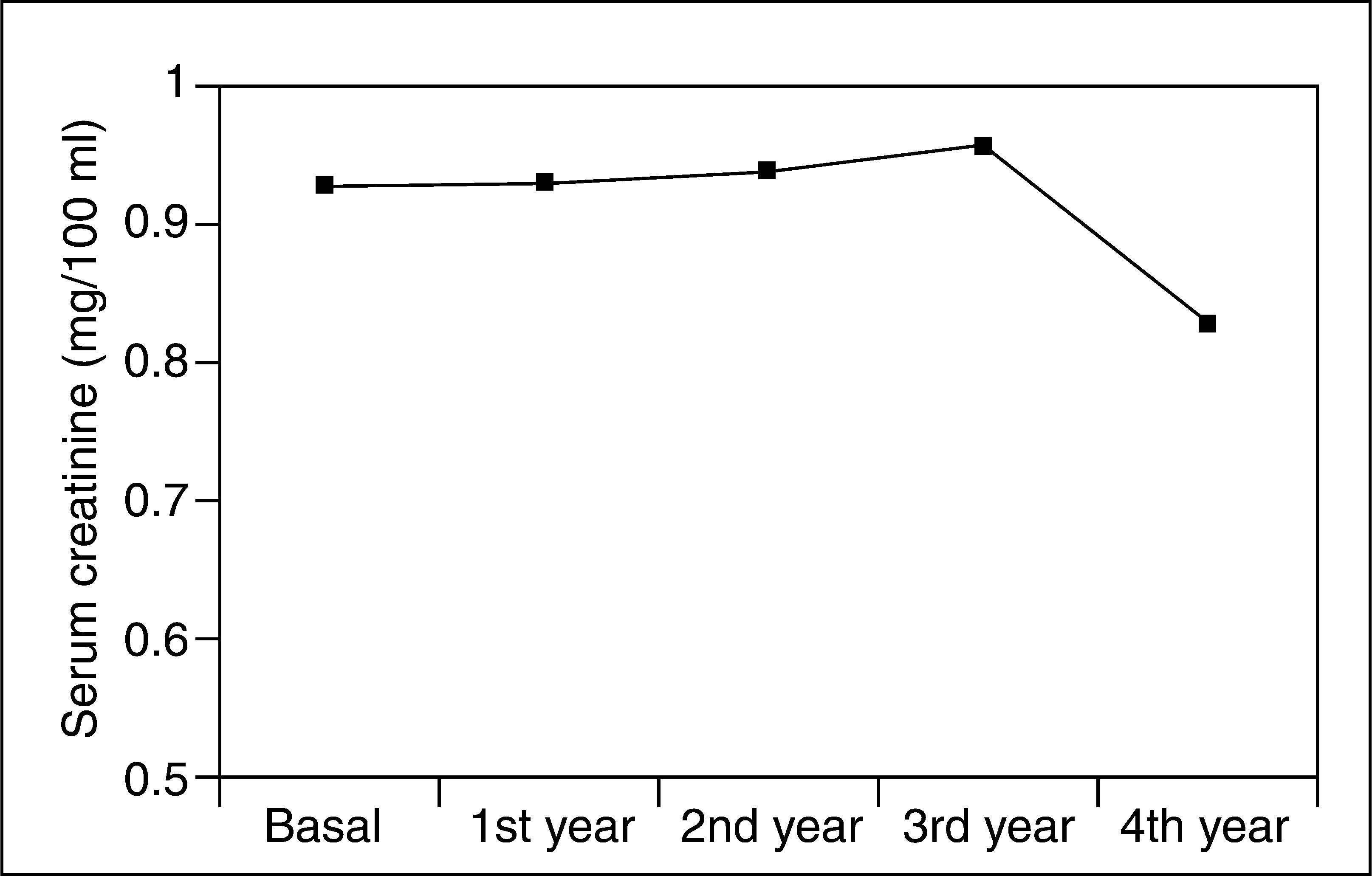

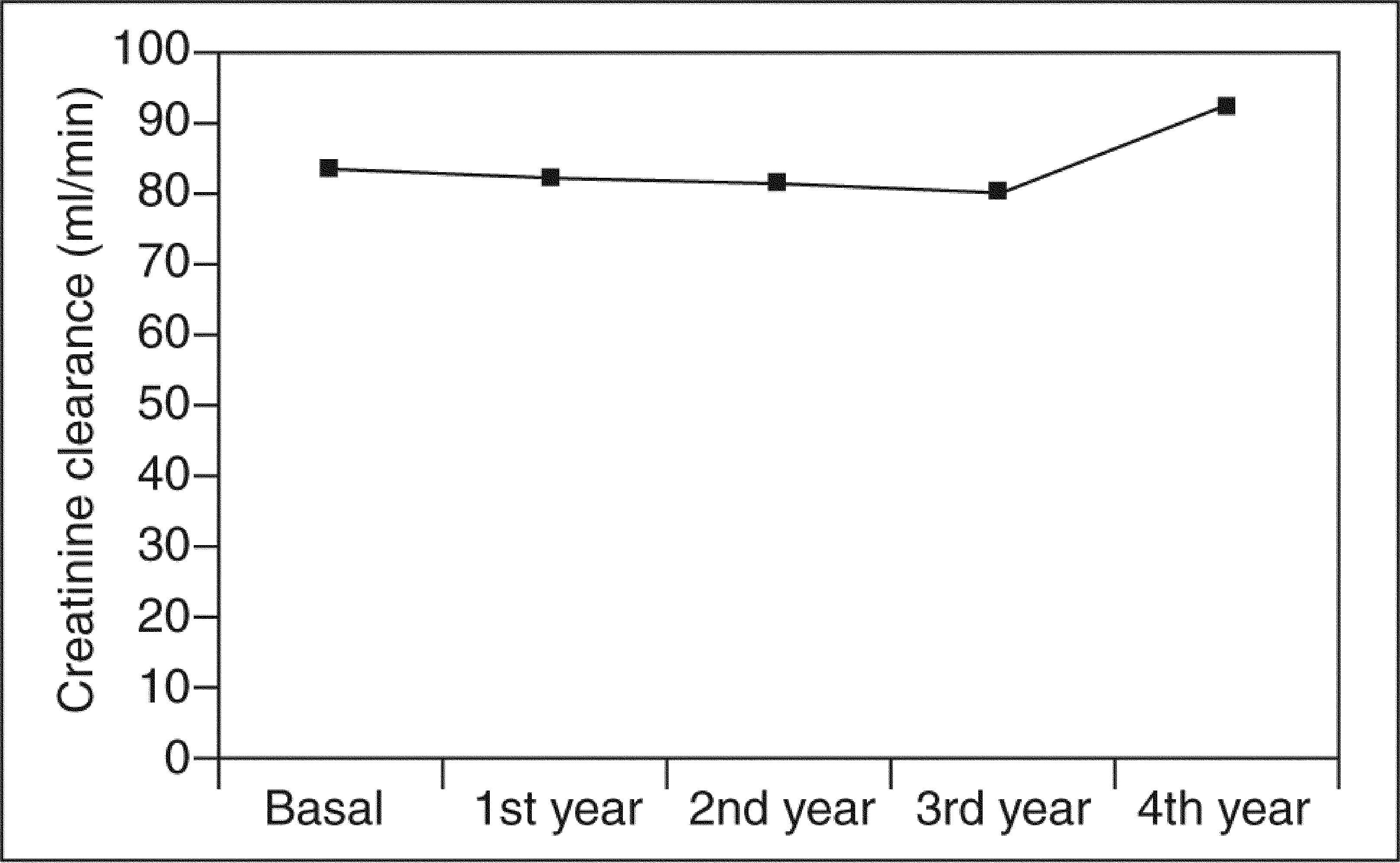

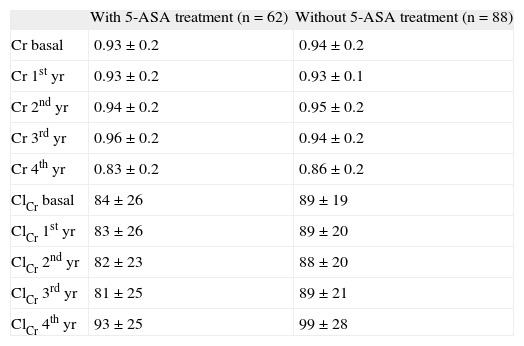

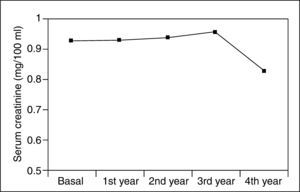

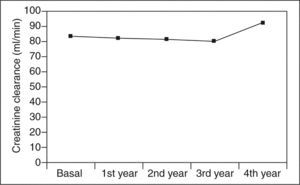

Serum creatinine levels at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 years in patients taking 5-ASAs remained stable (0.93 ± 0.2, 0.93 ± 0.2, 0.94 ± 0.2, 0.96 ± 0.2, and 0.83 ± 0.2 mg/100 ml) (fig. 1). Similarly, ClCr did not change for the 4-year follow- up in 5-ASA treated patients (84 ± 26, 83 ± 26, 82 ± 23, 81 ± 25, and 93 ± 25 ml/min) (fig. 2). Furthermore, values of both serum creatinine and ClCr were similar in patients with and without 5-ASA treatment (non-statistically significant differences at any time from 1 to 4 years) (table I).

Values of serum creatinine (Cr) and creatinine clearance (ClCr) in patients with and without 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) treatment

| With 5-ASA treatment (n = 62) | Without 5-ASA treatment (n = 88) | |

| Cr basal | 0.93 ± 0.2 | 0.94 ± 0.2 |

| Cr 1st yr | 0.93 ± 0.2 | 0.93 ± 0.1 |

| Cr 2nd yr | 0.94 ± 0.2 | 0.95 ± 0.2 |

| Cr 3rd yr | 0.96 ± 0.2 | 0.94 ± 0.2 |

| Cr 4th yr | 0.83 ± 0.2 | 0.86 ± 0.2 |

| ClCr basal | 84 ± 26 | 89 ± 19 |

| ClCr 1st yr | 83 ± 26 | 89 ± 20 |

| ClCr 2nd yr | 82 ± 23 | 88 ± 20 |

| ClCr 3rd yr | 81 ± 25 | 89 ± 21 |

| ClCr 4th yr | 93 ± 25 | 99 ± 28 |

The percentage of patients with moderate impairment of the estimated glomerular filtration rate at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 4 years was: 16.1% (95% CI, 9-27), 14.5% (7.8-25%), 12.9% (6.7-23%), 14.5% (7.8-25%), and 3.2% (0.9-11) (fig. 3); while the corresponding figure for severe impairment of the estimated glomerular filtration rate was 0% at all control times (fig. 3).

Finally, in the multivariate analysis, 5-ASA treatment (yes/no) did not correlate with serum creatinine levels or ClCr. Dose of 5-ASA was not predictive for change in renal function. No interstitial nephritis was reported during follow-up.

DISCUSSION5-ASA-related renal disease was not reported in our series, which suggests that the incidence of renal impairment in IBD patients receiving these drugs is exceptional. Furthermore, values of both serum creatinine and ClCr were similar in patients with and without 5-ASA treatment. Several studies have investigated the epidemiology of nephrotoxicity associated with 5-ASA use in patients with IBD. As an example, in the Dutch Pentasa study performed in 1995, two patients (1.3%) developed modest, reversible renal impairment, only one of whom had biopsy proven interstitial nephritis (which represents a rate of clinically significant interstitial nephritis of approximately 1 in 15012). In 1996, a review of eight published clinical trials of 5-ASA therapy in IBD concluded that renal impairment, defined as any increase in serum creatinine, may occur in up to 1 in 100 patients treated with this drug, but that the incidence of clinically significant interstitial nephritis was less than 1 in every 500 patients treated8. This same year, Marteau et al13 presented the safety reports on the use of Pentasa in France: spontaneous reports of adverse effects, submitted to a pharmaceutical manufacturer over a 2-year period, included 2 cases of renal impairment in approximately 45,000 patient-years of therapy13. One year later, Walker et al14 reviewed a large computerized database drawn from general practices in the UK; renal complications of 5-ASA therapy were extremely rare (0 and 0.2 cases per 100 patient-years for high-dose users of sulfasalazine and 5-ASA, respectively).

In 2002, Ransford and Langman15 evaluated serious adverse reactions reported to the Committee on Safety of Medicines of the UK in 1991-1998, noting 11.1 reports per million of prescriptions of interstitial nephritis associated with 5-ASA. This same year, a review of the literature included 18 clinical trials assessing the efficacy of 5- ASA preparations in the treatment of IBD for 6 months or more, and reported a prevalence of deterioration in renal function of only 0.06%16. In 2003, Logan et al17, in a large epidemiological study in the UK, included almost 40,000 patients and found that the overall incidence of renal damage was rare in patients taking 5-ASA drugs, but was increased relative to control patients (general population). More recently, data from the UK General Practice Research Database showed an incidence rate of 0.17 cases per 100 patients per year18. At the same time, in 2004, in a large European registry containing more than 1,500 patients with IBD, reported during a follow-up of 1 year, the incidence of renal failure was not increased in patients using 5-ASA19. Finally, a detailed postal questionnaire sent in 2004 to members of the British Society of Gastroenterology and the Renal Association20, calculated an incidence of 5-ASA nephrotoxicity of 1 in 4,000 patients/ year only.

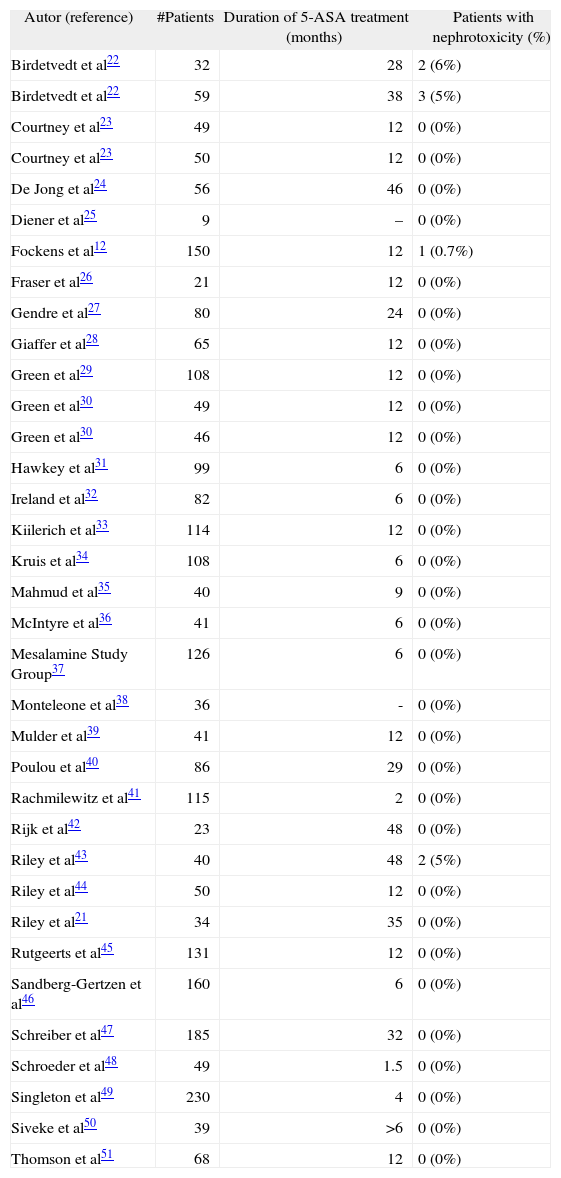

The renal impairment associated to 5-ASA use may be diagnosed at any interval after starting treatment. Thus, several studies have concluded that there is no relationship between duration of 5-ASA treatment and the risk of renal disease15,21, and that nephrotoxicity may appear from less than 1 month to more than 80 months after starting 5-ASA treatment5. However, most studies have included a relatively low number of patients and with a limited follow-up (of only several months). In our study, serum creatinine levels remained stable in patients taking 5-ASAs during the 4-year follow-up. Similarly, ClCr did not change in these 4 years in 5-ASA treated patients, and no interstitial nephritis was reported during follow-up. Studies with 5-ASA treatment in which serum creatinine or ClCr was measured regularly are summarized in table II12,21-51 –including a total of 2,671 patients receiving 5- ASA treatment during a total of 3,070 years of followup–, where it is shown that nephrotoxicity was exceptional, being reported in only a few studies12,22,43 (giving a mean annual nephrotoxicity rate of only 0.26% per patient- year of follow-up)5.

Studies with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) treatment in which serum creatinine or creatinine clearance was measured regularly

| Autor (reference) | #Patients | Duration of 5-ASA treatment (months) | Patients with nephrotoxicity (%) |

| Birdetvedt et al22 | 32 | 28 | 2 (6%) |

| Birdetvedt et al22 | 59 | 38 | 3 (5%) |

| Courtney et al23 | 49 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Courtney et al23 | 50 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| De Jong et al24 | 56 | 46 | 0 (0%) |

| Diener et al25 | 9 | – | 0 (0%) |

| Fockens et al12 | 150 | 12 | 1 (0.7%) |

| Fraser et al26 | 21 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Gendre et al27 | 80 | 24 | 0 (0%) |

| Giaffer et al28 | 65 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Green et al29 | 108 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Green et al30 | 49 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Green et al30 | 46 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Hawkey et al31 | 99 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Ireland et al32 | 82 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Kiilerich et al33 | 114 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Kruis et al34 | 108 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Mahmud et al35 | 40 | 9 | 0 (0%) |

| McIntyre et al36 | 41 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Mesalamine Study Group37 | 126 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Monteleone et al38 | 36 | - | 0 (0%) |

| Mulder et al39 | 41 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Poulou et al40 | 86 | 29 | 0 (0%) |

| Rachmilewitz et al41 | 115 | 2 | 0 (0%) |

| Rijk et al42 | 23 | 48 | 0 (0%) |

| Riley et al43 | 40 | 48 | 2 (5%) |

| Riley et al44 | 50 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Riley et al21 | 34 | 35 | 0 (0%) |

| Rutgeerts et al45 | 131 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

| Sandberg-Gertzen et al46 | 160 | 6 | 0 (0%) |

| Schreiber et al47 | 185 | 32 | 0 (0%) |

| Schroeder et al48 | 49 | 1.5 | 0 (0%) |

| Singleton et al49 | 230 | 4 | 0 (0%) |

| Siveke et al50 | 39 | >6 | 0 (0%) |

| Thomson et al51 | 68 | 12 | 0 (0%) |

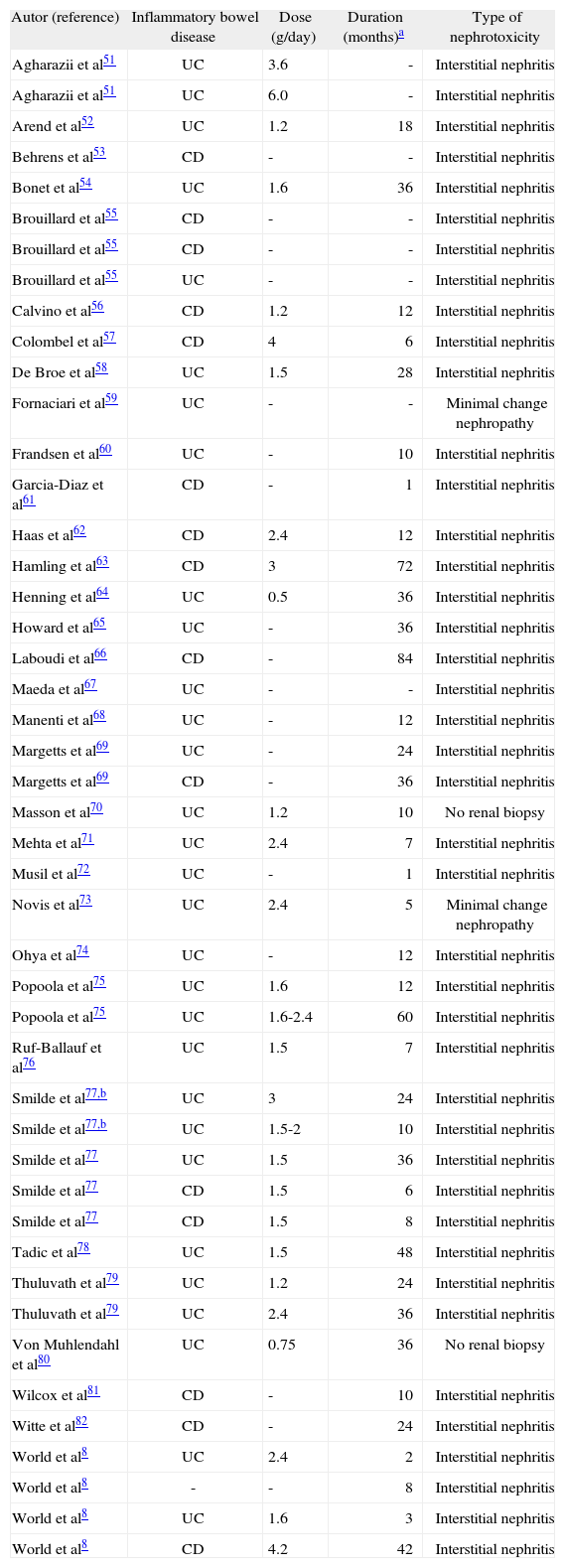

There have been several case reports of renal disease associated with 5-ASA treatment in patients with IBD (table III)8,52-83. The actual development of 5-ASA-related renal disease seems rare, as only 46 patients with this complication have been reported5. Thus, although the association between 5-ASA therapy and tubulo-interstitial nephritis is clearly described in several case reports, our study and other studies came to the reassuring conclusion that renal impairment in IBD patients is not frequently observed and is rarely associated with 5-ASA therapy. In the study by Elseviers et al19, all IBD patients seen at the outpatient clinic of 27 European centres of gastroenterology during 1 year were registered and screened for renal impairment controlling for a possible association with 5- ASA therapy. Renal screening (calculated ClCr) was performed at baseline, after 6 and 12 months. Decreased ClCr was observed in 34 patients, among which 13 presented chronic renal impairment. Comparing patients with and without renal impairment, no difference could be observed in 5-ASA consumption.

Case reports of patients with inflammatory bowel disease and renal disease associated with 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) treatment

| Autor (reference) | Inflammatory bowel disease | Dose (g/day) | Duration (months)a | Type of nephrotoxicity |

| Agharazii et al51 | UC | 3.6 | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Agharazii et al51 | UC | 6.0 | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Arend et al52 | UC | 1.2 | 18 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Behrens et al53 | CD | - | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Bonet et al54 | UC | 1.6 | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Brouillard et al55 | CD | - | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Brouillard et al55 | CD | - | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Brouillard et al55 | UC | - | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Calvino et al56 | CD | 1.2 | 12 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Colombel et al57 | CD | 4 | 6 | Interstitial nephritis |

| De Broe et al58 | UC | 1.5 | 28 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Fornaciari et al59 | UC | - | - | Minimal change nephropathy |

| Frandsen et al60 | UC | - | 10 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Garcia-Diaz et al61 | CD | - | 1 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Haas et al62 | CD | 2.4 | 12 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Hamling et al63 | CD | 3 | 72 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Henning et al64 | UC | 0.5 | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Howard et al65 | UC | - | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Laboudi et al66 | CD | - | 84 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Maeda et al67 | UC | - | - | Interstitial nephritis |

| Manenti et al68 | UC | - | 12 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Margetts et al69 | UC | - | 24 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Margetts et al69 | CD | - | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Masson et al70 | UC | 1.2 | 10 | No renal biopsy |

| Mehta et al71 | UC | 2.4 | 7 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Musil et al72 | UC | - | 1 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Novis et al73 | UC | 2.4 | 5 | Minimal change nephropathy |

| Ohya et al74 | UC | - | 12 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Popoola et al75 | UC | 1.6 | 12 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Popoola et al75 | UC | 1.6-2.4 | 60 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Ruf-Ballauf et al76 | UC | 1.5 | 7 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Smilde et al77,b | UC | 3 | 24 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Smilde et al77,b | UC | 1.5-2 | 10 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Smilde et al77 | UC | 1.5 | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Smilde et al77 | CD | 1.5 | 6 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Smilde et al77 | CD | 1.5 | 8 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Tadic et al78 | UC | 1.5 | 48 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Thuluvath et al79 | UC | 1.2 | 24 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Thuluvath et al79 | UC | 2.4 | 36 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Von Muhlendahl et al80 | UC | 0.75 | 36 | No renal biopsy |

| Wilcox et al81 | CD | - | 10 | Interstitial nephritis |

| Witte et al82 | CD | - | 24 | Interstitial nephritis |

| World et al8 | UC | 2.4 | 2 | Interstitial nephritis |

| World et al8 | - | - | 8 | Interstitial nephritis |

| World et al8 | UC | 1.6 | 3 | Interstitial nephritis |

| World et al8 | CD | 4.2 | 42 | Interstitial nephritis |

CD: Crohn’s disease; UC: ulcerative colitis.

In our study, dosage of 5-ASA was not predictive for change in renal function. In pre-clinical studies in animals nephrotoxicity appeared to be dose-related3. However, interstitial nephritis has been reported in patients taking doses of 5-ASA as low as 0.75 g/day81 or even 0.5 g/day65. Most of the cases of nephrotoxicity reported in the literature occurred in patients taking doses from 1.2 to 2.4 g/day, being relatively low5. Furthermore, several studies have concluded that there is no relationship between 5-ASA dose and the risk of renal disease15,18,19,21,24. Finally, some authors have evaluated urinary enzymes as markers of renal tubular damage in patients with IBD, and could not demonstrate a correlation between the enzymuria and the cumulative doses of 5-ASA84. Moreover, they showed normalization of these urinary enzymes with successful medical therapy (directed to IBD) despite increasing cumulative doses of 5-ASA84. In this respect, in a point prevalence study no clear distinction between the influence of disease activity and drug treatment can be made, if increased dosage of the anti-inflammatory drug used correlates highly with disease activity47. The low overall incidence of renal disease during 5-ASA treatment reported in the literature, together with the absence of a clear relationship between 5-ASA dose and the risk of nephrotoxicity, suggest that the renal reactions may be idiosyncratic rather than dose related in nature.

Our study has several methodological limitations. Firstly, its retrospective design, although the study variables were prospectively extracted in a predefined data extraction form. Secondly, renal function was monitored by measuring levels of serum creatinine. The shortcomings of serum creatinine as a marker of renal function are well-known, and this parameter is a poor marker of renal function despite its universal use for this purpose. It is significantly affected by a range of factors unrelated to glomerular filtration rate (e.g. sex, muscle mass and dietary meat intake)85. Furthermore, significant loss of functioning renal mass may occur before any rise in serum creatinine is apparent85. Therefore, more studies are necessary to determine whether serum creatinine gives sufficient warning of nephrotoxicity or whether more elaborate tests of renal function are required20. Because creatinine excretion was not regularly measured, we were unable to calculate endogenous ClCr. However, in coincidence with other studies19,24, ClCr in our patients was estimated from serum creatinine with the Cockroft and Gault formula, which takes into account age, weight, and sex10,11. The above formula gives a correlation coefficient between predicted and mean measured ClCr of 0.83, a figure that, although relatively high, is not perfect10. With this formula, the mean ClCr may be estimated reliably in groups of patients. However, in higher ranges of ClCr, the formula seems to underestimate ClCr, whereas ClCr seems to be overestimated in lower ranges3,11. Finally, due to the low incidence of 5-ASA related nephrotoxicity, thousands of patients would be needed to observe any significant difference between exposed and non-exposed subjects86. Thus, analytical epidemiological research (prospective cohort study or case-control study) needs the inclusion of a very large number of IBD patients. It has been emphasized the need for timely recognition of renal impairment and prompt discontinuation of 5-ASA treatment of affected patients. By not doing so, patients are placed, in theory, at risk for developing irreversible kidney damage. Thus, despite a lack of evidence that monitoring of serum creatinine is necessary or effective in patients receiving 5-ASA treatment, it has been suggested that there is a need for this analytical control. However, the optimal monitoring schedule remains to be established as there is no evidence to date that either the test, or the frequency of testing, is effective in identifying these patients at risk of developing 5-ASA-related renal impairment. Therefore, there are no firm recommendations, supported by medical evidence, for renal function monitoring (type and frequency) in IBD patients treated with these drugs5. Consequently, the «recommendations» regarding systematic screening for renal impairment should be considered as being «suggestions» and not as medically necessary based upon the review of the literature, as there is presently no evidence that such screening or monitoring improves patient outcomes5.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTCIBEREHD is funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III.