Hepatic angiosarcoma (HAS) is a rare malignancy that accounts for 2% of all hepatic primary tumors.1 It has been related to exposure to chemical carcinogens.1,2 The diagnosis is challenging due to the lack of specificity of the symptoms and the heterogeneous appearance on radiologic images, especially if the patient does not have previous history of occupational exposure.

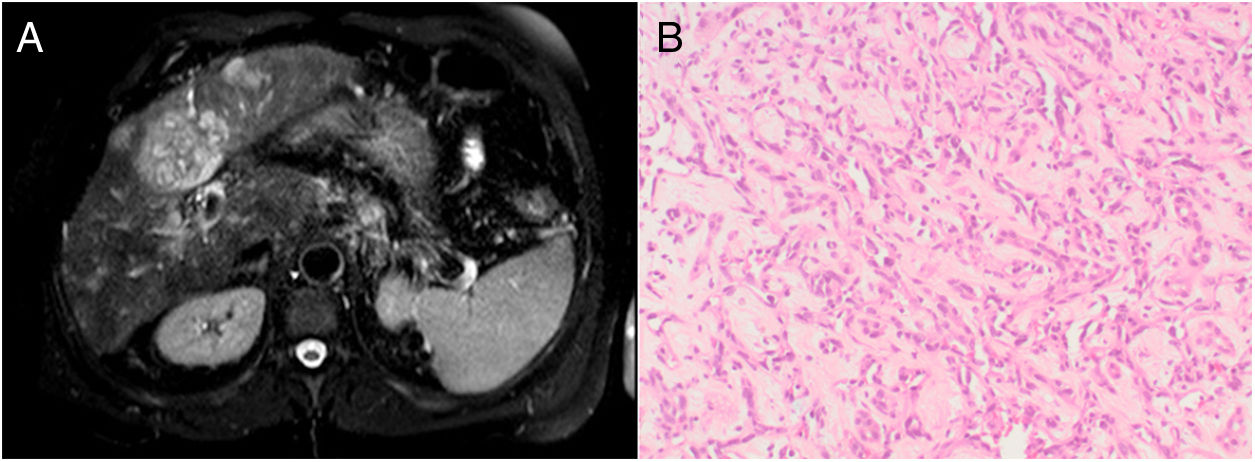

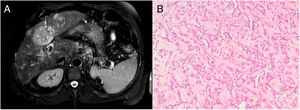

Description of the caseA 64-year-old male with heavy alcohol consumption, previous spontaneously resolved HBV infection but no occupational exposure risk factors, was admitted to hospital for hematemesis. Blood tests were as follows: hemoglobin 15.3g/dL (13.5–18); platelet count 51000/μL (150000–400000); international normalized ratio (INR) 1.44; bilirubin 2.91mg/dL (0.2–1.0); albumin 2.4g/dL (3.2–4.8); aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 76U/L (10–34); alanine transaminase (ALT) 51U/L (10–44) and γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) 254U/L (11–50). Urgent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed bleeding from esophageal varices, which was controlled with rubber-band ligation. An abdominal ultrasound examination was consistent with cirrhosis and it also showed multiple nonspecific hepatic nodules. Multiphase computerized tomography (CT) and a magnetic resonance (MRI) imaging revealed multifocal and isodense hypovascular masses in precontrast images. In some lesions, peripheral enhancement was seen in the arterial phase. There was no definite washout (Fig. 1A). Due to these findings, inconsistent with hepatocellular carcinoma, the patient underwent percutaneous liver biopsy, revealing a diffuse infiltration by a vascular malignancy with a high degree of atypia and cellular pleomorphism (Fig. 1B), expressing CD31, CD34 and Factor VIII. A positron emission computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed multiple bone infiltration.

Due to the impaired liver function and the presence of thrombocytopenia, targeted therapy with Pazopanib was started. Two weeks later, the patient was readmitted for severe encephalopathy and a Brain MRI confirmed the diagnosis of a posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES). The patient passed away three days later.

DiscussionHAS is a rare entity but nonetheless represents the most frequent mesenchymal malignancy of the liver.1,2 It originates from liver vascular endothelial cells and lymphatic vessels cells.1 Around 200 cases are diagnosed annually worldwide.

HAS is associated with exposure to chemical carcinogens, including vinyl chloride, radiocontrast material, thorium dioxide, androgenic steroid and arsenic.1,2,4 Despite all the risk factors described, in most cases the etiology is unknown and so, the diagnosis is challenging.

Reports regarding the association of HAS with cirrhosis have thrown contradictory findings. Some studies suggest an association between both entities2,5 while others argue against.4 Locker et al. reviewed 103 cases of HAS. Among those (60/103) with no definite exposure to chemicals, only 3 were found to have liver disease. On the other hand, Pickhardt et al.5 reported 15 cases (42.9%) of liver cirrhosis among 35 HAS cases and a positive association with liver cirrhosis was also found by Soini et al. In some of these reports, patients present alcoholic liver cirrhosis; however, alcohol consumption has not been demonstrated to be a carcinogen related to the appearance of HAS.5 Data from a study carried out in Taiwan,4 an endemic area of viral hepatitis B, does not support HBV infection or HBV-cirrhosis being a risk factor for HAS.

Symptoms are nonspecific. Abdominal pain, weakness, fatigue and weight loss are frequent. The most common clinical findings are hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, jaundice and anemia. Due to his rapid growth, it has been related to acute liver failure and cirrhosis decompensation. Spontaneous rupture has been reported.

The diagnosis requires careful assessment of imaging findings and histological evaluation.5 Common imaging findings include rapidly progressive multifocal tumors and hypervascular foci on the late arterial phase. Large hypovascular regions are common. In cirrhotic livers, lack of tumor washout of hypervascular lesions argues against hepatocellular carcinoma and makes histopathological analysis mandatory. Histopathology may show different patterns of vascular channels and dilated sinusoidal or cavernous spaces. Tumor cells express CD34, CD31 and factor VIII-related antigen.1

Differential diagnosis must be established with other entities such as cavernous haemangiomas, hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma or hepatic peliosis.

Survival rates are poor (median survival of 5 months).3 Standard treatment is surgical resection, although is only feasible in less than 20% of cases. Liver transplant is contraindicated due to high recurrence rate. Patients with metastatic angiosarcoma are treated with chemotherapy although no specific regimens have been established.3

In this case, no chemical exposure was found. As radiological findings were inconsistent with hepatocellular carcinoma, a liver biopsy was carried out. The patient had not presented previous cirrhosis-related decompensations. The rapid growth of the tumor might have been the trigger for the variceal bleeding.

Liver cirrhosis may play a role in the development of HAS. However, there is not enough evidence to support this association yet. Through a multicenter joint effort, a most accurate characterization of this rare entity may be possible, therefore allowing to clarify the association between cirrhosis and HAS.

Financial supportThe authors received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.