Multidisciplinary units are needed because of the growing complexity and volume of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

ObjectivesTo evaluate the healthcare, economic and research impact of incorporating a nurse into the IBD unit of the Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda University Hospital.

MethodsWe prospectively recorded the activity carried out by the nurse of the IBD unit from March 2010 to December 2014.

ResultsDuring this period, healthcare demand progressively increased, with 1558 patients being attended by our unit. The healthcare provided by the nurse included 5293 electronic mails and 678 telephone calls. We estimated that this activity represented a saving of 3504 in-person medical consultations and 852 accident and emergency department visits. Other activities consisted of monitoring treatments with biological and non-biological agents (8371 laboratory tests), extraction of 342 blood samples, follow-up of 1047 diagnostic tests and consultations with other medical specialties, health education in self-administration of drugs in 114 patients, the performance of 158 granulocyte apheresis procedures, and participation in 25 research projects.

ConclusionThe incorporation of a specialised nurse in an IBD unit had major economic, healthcare and research benefits.

La complejidad y el volumen crecientes de los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) obligan a desarrollar equipos multidisciplinares. La enfermería especializada debería ser parte de estas unidades tal y como se recoge en diferentes documentos de consenso.

ObjetivosEvaluar el impacto que la incorporación de la enfermería a la Unidad de EII del Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda (HUPHM) ha tenido desde el punto de vista asistencial, económico e investigador.

MétodosRecogida prospectiva de la actividad desempeñada por la enfermera de la Unidad de EII del HUPHM desde marzo del 2010 hasta diciembre del 2014.

ResultadosEn este periodo se ha producido un aumento progresivo de la demanda asistencial, que ha alcanzado los 1.558 pacientes atendidos por nuestra Unidad. La asistencia proporcionada por la enfermera alcanzó un total de 5.293 correos electrónicos y de 678 llamadas telefónicas. Con ello, se estima que esta actividad ha supuesto un ahorro de 3.504 consultas médicas presenciales así como de 852 visitas al Servicio de Urgencias. Otras actividades realizadas han sido la monitorización de tratamientos con medicamentos biológicos y no biológicos (8.371 controles analíticos), la extracción de 342 analíticas, el seguimiento de 1.047 pruebas diagnósticas e interconsultas a otras especialidades médicas, la educación sanitaria en la autoadministración de medicamentos a 114 pacientes, la realización de 158 granulocitoaféresis y la participación en 25 proyectos de investigación.

ConclusionesLa incorporación de la enfermera especializada a la Unidad de EII tiene un gran impacto beneficioso tanto desde el punto de vista asistencial y económico como investigador.

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) encompasses Crohn disease and ulcerative colitis. Both diseases are characterised by producing an abnormal immune response in the intestine. They are chronic diseases that alternate periods of remission with periods of inflammatory activity. They can become disabling, and have a huge impact on the quality of life of the patient and their family.1

The increased incidence and prevalence of IBD in Spain,2–6 as well as the growing complexity of the therapeutic approach to these patients, requires the formation of specialised multidisciplinary teams. In this respect, several consensus documents have highlighted the need for specialised nurses capable of contributing skills that complement those of the doctor at both the healthcare level and in research. However, in many hospitals the specialist IBD team does not include a nurse. Whether the inclusion of a nurse in the team of professionals who care for patients IBD will be a cost-saving measure and improve the level of care in our setting remains to be seen.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact on routine clinical practice of the incorporation of a nurse in our IBD unit.

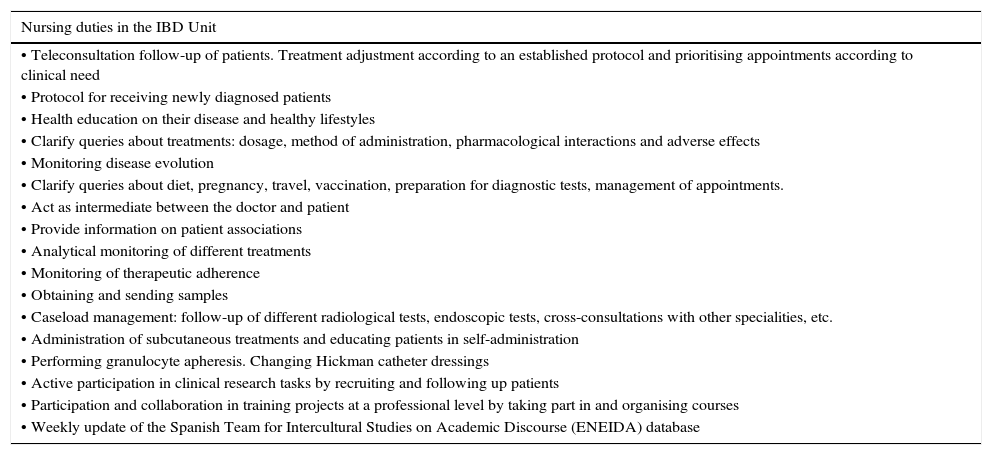

Materials and methodsData on the activity undertaken by the nurse in the IBD unit of the Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda University Hospital (Madrid, Spain) were collected prospectively from March 2010 until December 2014. Table 1 shows the activities carried out by the nurse in our unit.

Nursing duties in the IBD Unit in Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro Majadahonda.

| Nursing duties in the IBD Unit |

|---|

| • Teleconsultation follow-up of patients. Treatment adjustment according to an established protocol and prioritising appointments according to clinical need |

| • Protocol for receiving newly diagnosed patients |

| • Health education on their disease and healthy lifestyles |

| • Clarify queries about treatments: dosage, method of administration, pharmacological interactions and adverse effects |

| • Monitoring disease evolution |

| • Clarify queries about diet, pregnancy, travel, vaccination, preparation for diagnostic tests, management of appointments. |

| • Act as intermediate between the doctor and patient |

| • Provide information on patient associations |

| • Analytical monitoring of different treatments |

| • Monitoring of therapeutic adherence |

| • Obtaining and sending samples |

| • Caseload management: follow-up of different radiological tests, endoscopic tests, cross-consultations with other specialities, etc. |

| • Administration of subcutaneous treatments and educating patients in self-administration |

| • Performing granulocyte apheresis. Changing Hickman catheter dressings |

| • Active participation in clinical research tasks by recruiting and following up patients |

| • Participation and collaboration in training projects at a professional level by taking part in and organising courses |

| • Weekly update of the Spanish Team for Intercultural Studies on Academic Discourse (ENEIDA) database |

The nurse is the communication link between the unit and patients. Patients communicate with the unit via telephone or e-mail (teleconsultation), and these are received by the unit nurse. Information on how to directly access the nurse is provided on cards that are given to the patients and their carers. The administrative staff are in charge of answering the telephone and noting the needs of patients attending the unit in person, and pass these messages to the nurse within working hours. E-mails are managed directly by the nurse, with a commitment to answer within 24h on working days, either by e-mail or by telephone.

Any situation that would have required a medical visit, but which–after consulting the doctor responsible for that patient and the document approved by Nursing Management—was resolved by the unit nurse via e-mail or telephone call was defined as an “averted consultation”. Averted consultations included: clarification of queries about treatment (dosage, method of administration, pharmacological interactions, adverse effects), diet, pregnancy, travel, vaccinations, preparation for diagnostic tests, follow-up of flare-ups, and monitoring of biological and non-biological treatments.

A “referred consultation” was any situation in which the patient needed to be seen by their doctor at the clinic. Referred consultations included: follow-up of a patient who, after establishing treatment by teleconsultation, did not note any improvement in symptoms.

An “averted emergency” was defined as a flare-up that would have required patients to visit the emergency department. After consulting the patient's doctor, they were given instructions and the visit was averted.

A “referred emergency” was defined as any situation in which the patient required assessment by the emergency department. Referred emergencies included: the presence of fever while under immunosuppressive or biological treatment, abdominal pain, vomiting, or high number of bowel movements, indicating the presence of severe disease complications.

There are 5 simultaneous specialised IBD clinics, attended by physicians from the unit. The nurse is present in this area, and helps in the clinics as required. This allows her to carry out the rest of her duties described in Table 1.

The cost analysis was based on public prices for the provision of healthcare services and health-related activities published in September 2013 by the Community of Madrid.6 These included: subsequent specialised medical consultation (€78), general hospital emergency with no admission (€180), subsequent medical consultation in Primary Care (€39), and nursing consultation in Primary Care (€18).

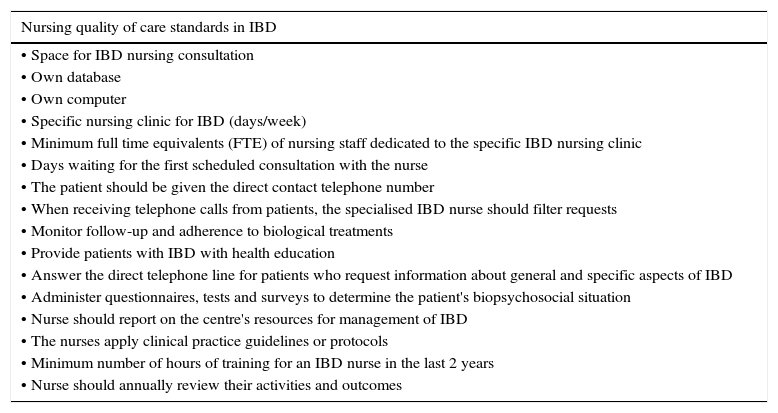

Finally, the nursing activity in our unit was validated according the quality standards developed in our setting (Table 2).7

Criteria required to classify the quality of care of the IBD by nursing staff.

| Nursing quality of care standards in IBD |

|---|

| • Space for IBD nursing consultation |

| • Own database |

| • Own computer |

| • Specific nursing clinic for IBD (days/week) |

| • Minimum full time equivalents (FTE) of nursing staff dedicated to the specific IBD nursing clinic |

| • Days waiting for the first scheduled consultation with the nurse |

| • The patient should be given the direct contact telephone number |

| • When receiving telephone calls from patients, the specialised IBD nurse should filter requests |

| • Monitor follow-up and adherence to biological treatments |

| • Provide patients with IBD with health education |

| • Answer the direct telephone line for patients who request information about general and specific aspects of IBD |

| • Administer questionnaires, tests and surveys to determine the patient's biopsychosocial situation |

| • Nurse should report on the centre's resources for management of IBD |

| • The nurses apply clinical practice guidelines or protocols |

| • Minimum number of hours of training for an IBD nurse in the last 2 years |

| • Nurse should annually review their activities and outcomes |

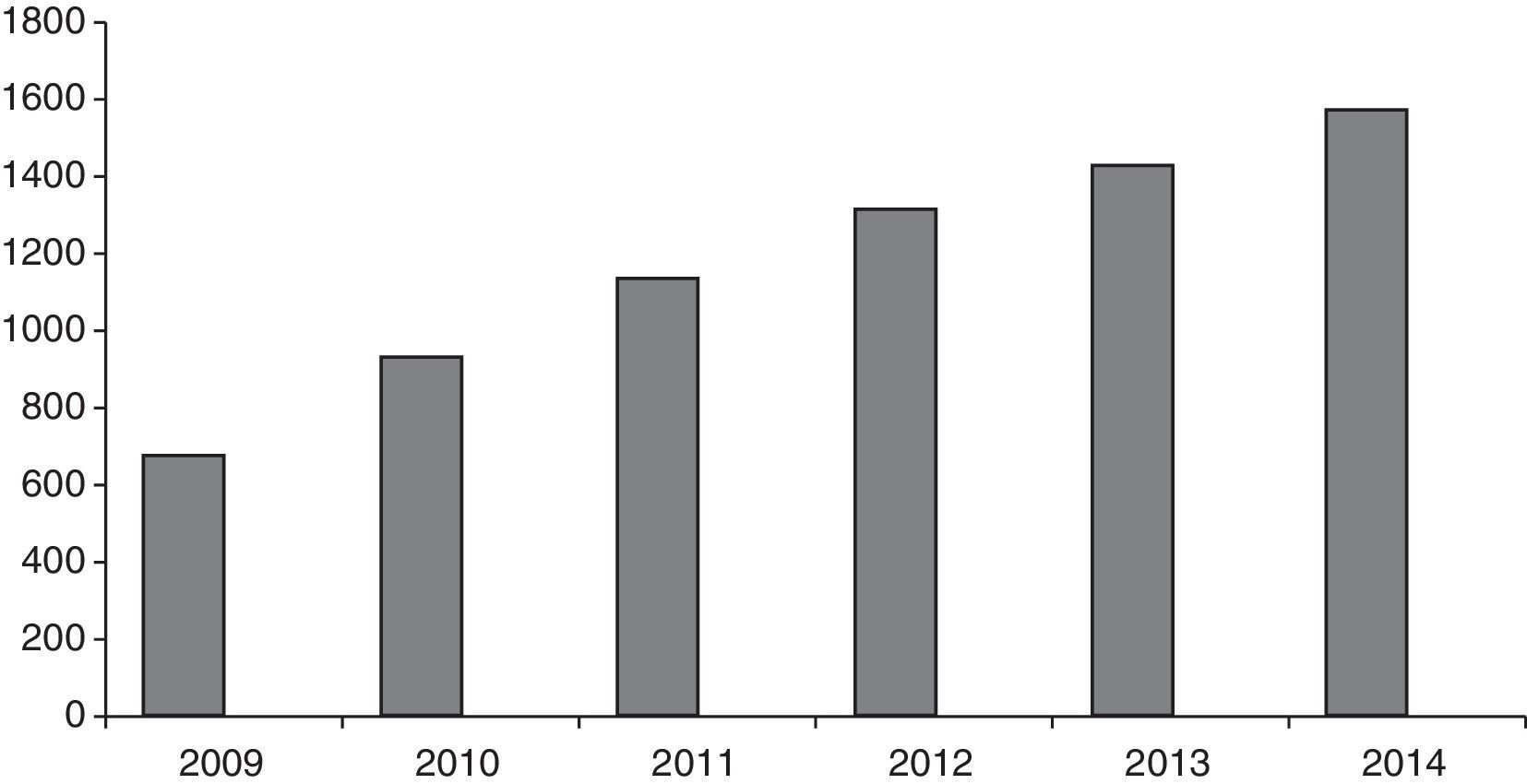

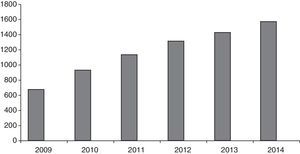

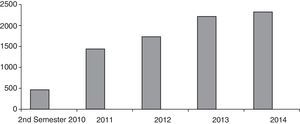

The number of patients seen in our unit gradually increased, as shown in Fig. 1. The total number of patients at the time the study was conducted was 1558. The number of new patients seen in these 4 years totalled 885.

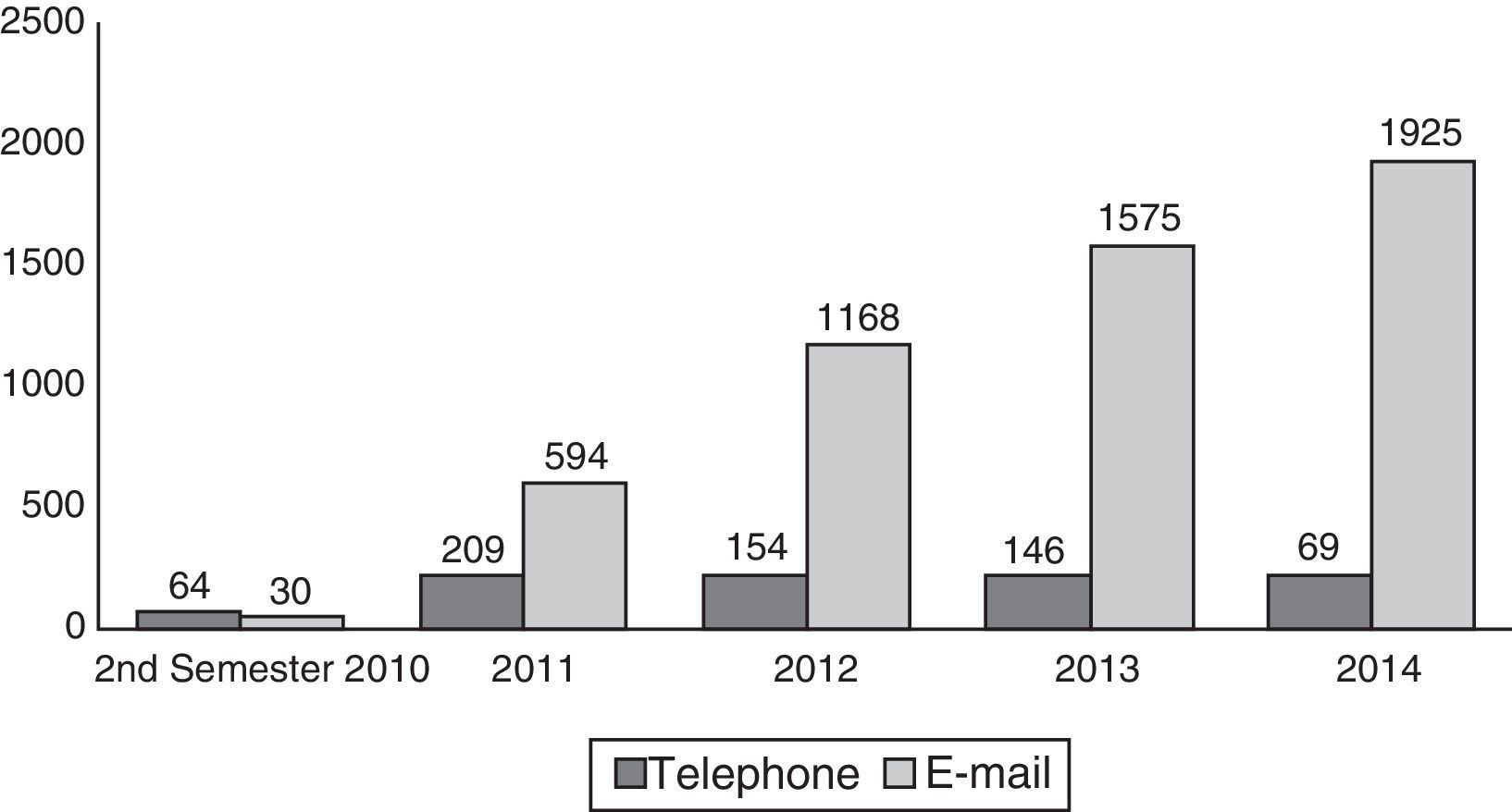

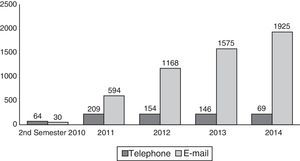

With respect to telephone calls and e-mails attended by the unit nurse in the study period, a total of 5293 e-mails and 678 telephone calls were answered, with a gradual increase in this activity over the study period (Fig. 2).

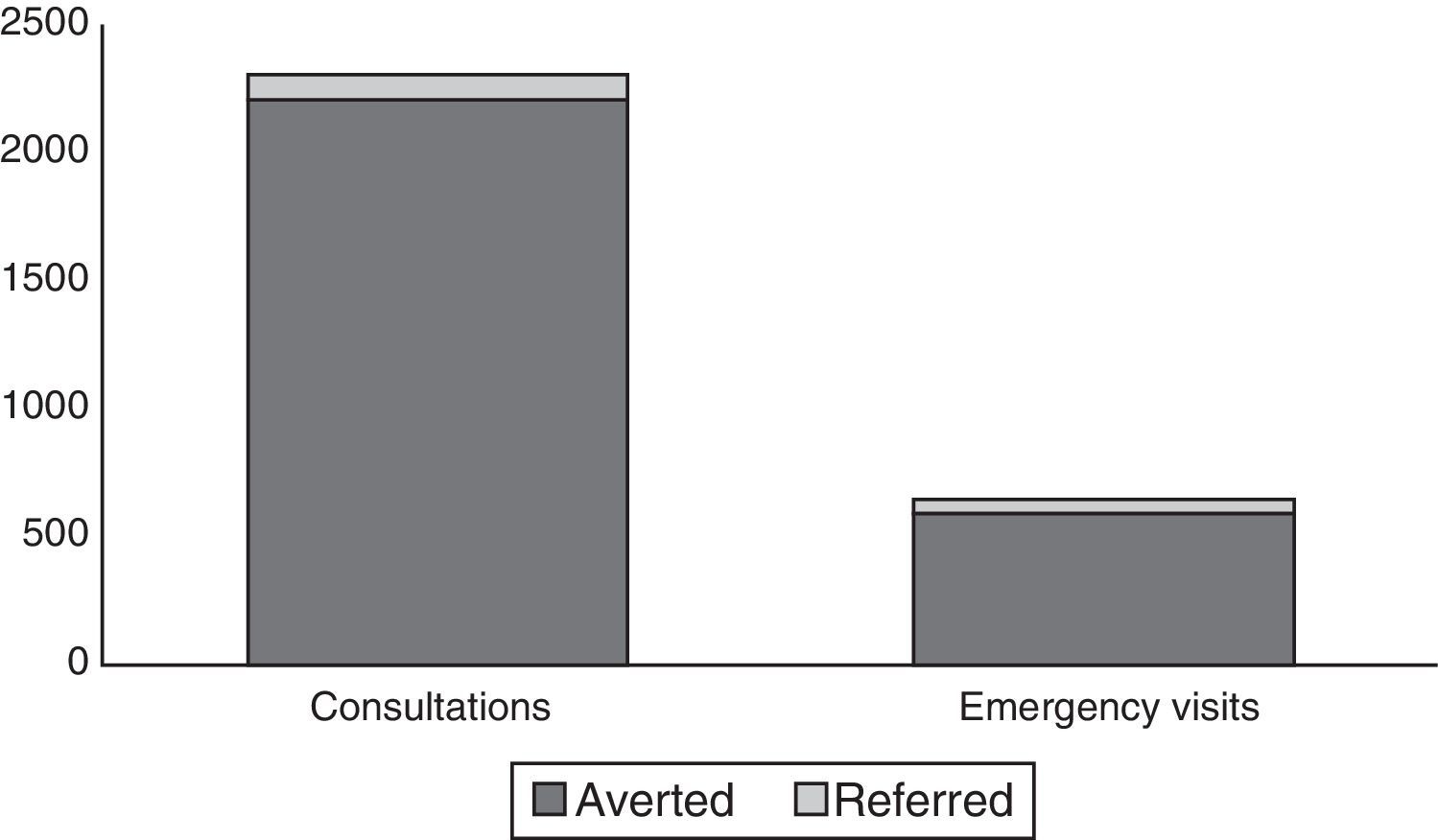

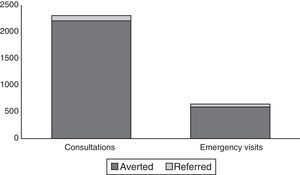

Answering these calls and e-mails was estimated to have averted 3504 medical consultations as well as 852 visits to the emergency department (Fig. 3), at an estimated saving of €426,672.

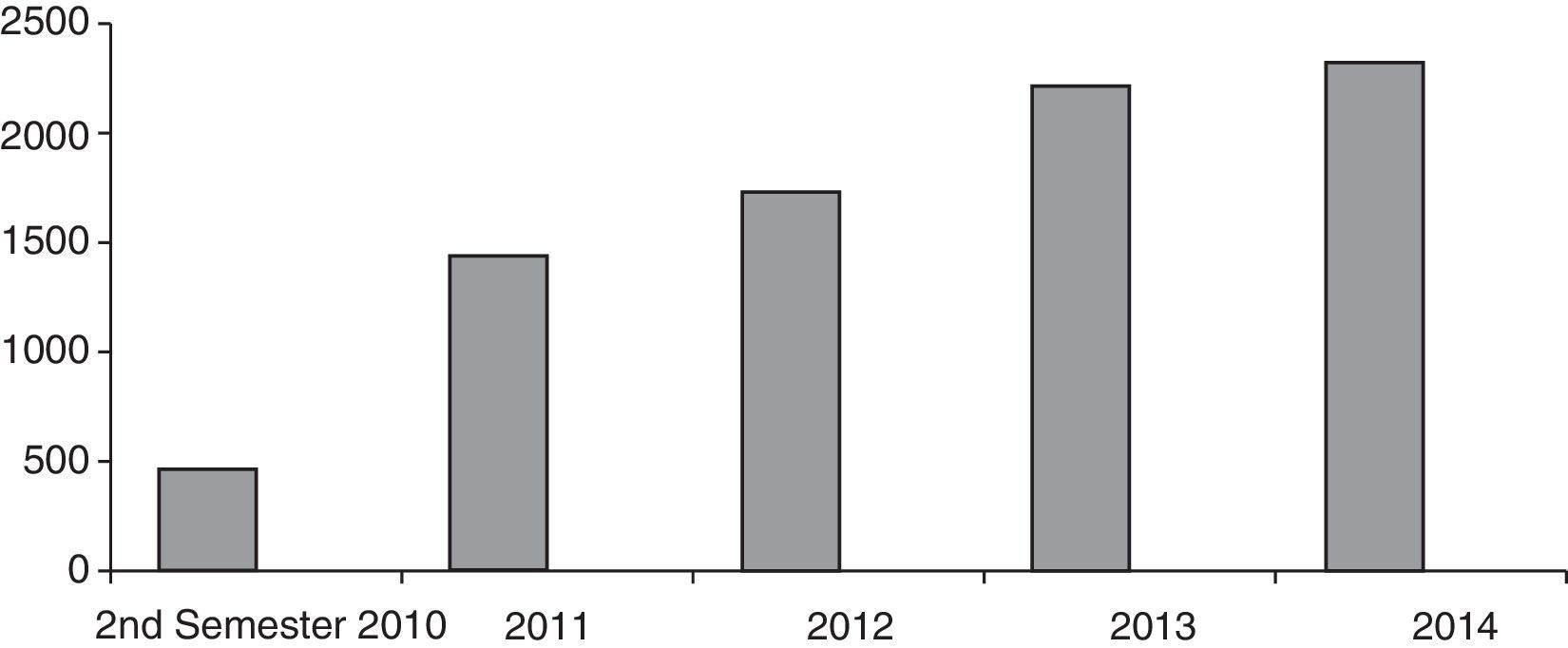

A total of 8371 laboratory tests relating to the different biological and non-biological treatments administered were followed-up (Fig. 4), and adherence to these treatments was monitored. A total of 342 blood samples were extracted.

The unit nurse managed and followed up 1047 cases, which included radiological tests (abdominal computed tomography [CT], magnetic resonance enterography), endoscopic tests (colonoscopy and gastroscopy), cross-consultations with other medical or nursing specialists (rheumatology, gynaecology, ophthalmology, dermatology, general and gastrointestinal surgery, preventive medicine, smoking unit, stoma unit), checking the status of the vaccination calendar (serology and Mantoux/booster), and faecal calprotectin and stool culture.

The nurse taught 114 patients and their carers how to administrate and store different self-administered treatments (subcutaneous treatments), as well as describing their adverse effects and advising on precautions that should be taken.

One hundred and fifty-eight granulocyte apheresis procedures were carried out. Some patients wore Hickman catheters, so 41 dressings were changed.

During this time, the nurse participated in 25 research projects, including recruitment and follow-up of 492 patients. The nurse also attended 23 conferences, 5 as speaker and 2 as secretary.

The other tasks included in Table 1 are unquantifiable tasks.

Finally, all these activities were graded according to the quality standards proposed in our setting as level A, or high quality.

DiscussionThe number and complexity of patients with IBD is rising, and requires the creation of specialised teams who can respond to the increasingly specific care needs of these patients. These teams must be multidisciplinary, as many professionals participate in the care of patients with IBD.8,9 The role of specialised nurses in IBD is widely recognised, and they should play a crucial role in the management of these patients, as their skills complement those of other professionals and improve the overall care received by them.9–14 However, they are seldom included in IBD teams, and are not available in many centres.

IBD is a chronic disease that alternates periods of remission with periods of activity. Patients experience episodes of symptoms that can be caused by either the illness or its complications, leading them to make frequent hospital visits, requiring evaluation by their doctor. Patients with IBD need simple, rapid access to health professionals to avoid the risk of exacerbation of their symptoms, their disease, and the occupational problems, social isolation or emotional overload that accompany the disease.10,15 IBD units try to respond to these needs, and patient perception of the care they receive has improved. This has been largely due to the provision of teleconsultation by telephone or e-mail, one of the basic pillars of a new approach that provides more direct, speedy and personalised care, and also averts many visits to hospital.16,17 Our experience corroborates this, as the number of consultations attended in this manner by our unit nurse has grown enormously since the introduction of teleconsultation in 2010. The initiative was well received by our patients, especially as regards access via e-mail: a very substantial number of e-mails were answered every day, which means easy access to the unit with no restriction on receiving messages. E-mail, therefore, was the method most widely used by our patients to communicate with our unit, although a smaller but steady proportion of consultations were made by telephone. Despite the growing use of new technology in all sectors of the population, some patients still prefer to use the telephone rather than Internet, as it provides them with greater security by establishing physical contact with another person.

Similarly, the existence of these specialised IBD units reduces both the number and length of hospital admissions, due to the direct contact that the patient maintains with the unit.18,19 The benefits of using information and communication technology in the care of chronic patients has been demonstrated in various studies,20,21 and is further corroborated by our experience. The introduction of teleconsultation, which in our case is run by the unit nurse, has led to substantial savings by averting a high number of consultations and visits to the emergency department. These consultations involved analytical monitoring of various treatments as well as adherence to these treatments, answering questions about the disease, about treatment (generally adverse effects or pharmacological interactions), pregnancy, diet, preparing for diagnostic tests, vaccinations, travel, surgery, what to do in the event of a flare-up, and the frequency of laboratory tests. This prevented overburdening outpatient consultations, with the corresponding benefit in terms of opportunity cost, thus optimising resources (time, staff) and allowing them to be channelled to patients who really need them at any given time.

The role of IBD Units and their quality criteria have been defined in various consensus documents,9,22 which also establish the central role of the specialised nurse.9,20–25 Thus for example, the Nurses-European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (N-ECCO) drew up a document with the aim of identifying the needs of patients with IBD that should be met by the nurse, and providing a consensus on the minimum standard of care that these patients should receive. These could include the following: better access to the nurse via telephone and e-mail; the ability to evaluate the patient's clinical status, perform diagnostic examinations, modify treatment, adequately supervise and review the status of patients with IBD using treatment guidelines; provide emotional and physical support; reduce the number of outpatient visits and waiting times and, fundamentally, carry out caseload management, which is a major contributing factor and complements conventional follow-up in these patients.

Furthermore, the nurse provided the patients seen in our unit with education on their disease and guidelines for a healthy lifestyle, advised them on their treatment and its possible adverse effects, monitored disease progression and clarified doubts about diet, pregnancy, travel, preparation for diagnostic tests, and management of appointments. The nursing care provided in our unit, recorded in a document approved by Nursing Management, met the standards previously set in consensus documents,7 although areas for improvement were detected, such as the need for the nurse's own area or schedule.

Numerous studies show the positive impact of the specialised nurse in IBD, and although their role and the resources available to them vary greatly in our setting, it seems clear that if nursing duties are defined according to protocols carried out by trained nursing staff, the comprehensive care of the patient and their satisfaction with the care received improve enormously.10–14,26,27

Finally, the research potential of the specialised nurse is incalculable. In our unit, this allowed us to undertake a significant number of projects that would never have been possible without the help and active participation of the nurse.

Specialised nurses help patients understand their disease, establish direct contact with them, and act as a link between their different specialists, providing a necessary complement to the comprehensive care required by patients with IBD. In short, specialised nurses improve care and research activity, optimise resources and save costs, making their presence in IBD teams fully justified.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Amo L, González-Lama Y, Suárez C, Blázquez I, Matallana V, Calvo M, et al. Impacto de la incorporación de la enfermera a una unidad de enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:318–323.