Barrett's oesophagus (BE) is an oesophageal injury caused by gastroesophageal acid reflux. One of the main aims of treatment in BE is to achieve adequate acid reflux control.

ObjectiveTo assess acid reflux control in patients with BE based on the therapy employed: medical or surgical.

MethodsA retrospective study was performed in patients with an endoscopic and histological diagnosis of BE. Medical therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPI) was compared with surgical treatment (Nissen fundoplication). Epidemiological data and the results of pH monitoring (pH time <4, prolonged reflux >5min, DeMeester score) were evaluated in each group. Treatment failure was defined as a pH lower than 4 for more than 5% of the recording time.

ResultsA total of 128 patients with BE were included (75 PPI-treated and 53 surgically-treated patients). Patients included in the two comparison groups were homogeneous in terms of demographic characteristics. DeMeester scores, fraction of time pH <4 and the number of prolonged refluxes were significantly lower in patients with fundoplication versus those receiving PPIs (p<.001). Treatment failure occurred in 29% of patients and was significantly higher in those receiving medical therapy (40% vs 13%; p<.001).

ConclusionsTreatment results were significantly worse with medical treatment than with anti-reflux surgery and should be optimised to improve acid reflux control in BE. Additional evidence is needed to fully elucidate the utility of PPI in this disease.

El esófago de Barrett (EB) es una lesión esofágica ocasionada mayoritariamente por reflujo gastroesofágico ácido. El control del reflujo ácido es uno de los principales objetivos del tratamiento de esta patología.

ObjetivoEvaluar en nuestra área de salud el grado de control del reflujo ácido en los pacientes con EB en función del tratamiento de mantenimiento recibido, médico o quirúrgico.

MétodosEstudio retrospectivo de pacientes con diagnóstico endoscópico e histológico de EB. Un grupo de pacientes recibió tratamiento médico con inhibidores de la bomba de protones (IBP) y otro grupo fue sometido a intervención quirúrgica (funduplicatura de Nissen). Se compararon datos epidemiológicos y resultados de pHmetría (tiempo de pH<4, reflujos prolongados >5min, puntuación de DeMeester) de cada grupo. La pH-metría se realizó con IBP en el grupo de tratamiento médico y en el grupo de cirugía sin consumo de antisecretores ácidos. Se definió fracaso del tratamiento como un pH<4 total superior al 5%.

ResultadosFueron incluidos 128 pacientes con EB (tratamiento médico 75, tratamiento quirúrgico 53). Ambas cohortes eran homogéneas respecto a sus características demográficas. Las puntuaciones de DeMeester, fracción de tiempo de pH<4 y cantidad de reflujos prolongados fueron significativamente inferiores en los pacientes con funduplicatura frente a los que recibían IBP (p<0,001). De forma global se apreció un fracaso de tratamiento en el 29% de los pacientes, que fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de tratamiento médico (40% vs 13%; p<0,001).

ConclusionesEl grado de control del reflujo ácido gastroesofágico es subóptimo en un elevado porcentaje de pacientes con EB. El tratamiento médico ofrece resultados inferiores a la cirugía antirreflujo y se debería intentar optimizar sus resultados.

Barrett's oesophagus (BO) is characterised by replacement of the oesophageal squamous epithelium by metaplastic columnar epithelium. BO, an oesophageal injury caused by severe, chronic gastro-oesophageal reflux,1 is the primary risk factor for developing oesophageal adenocarcinoma (OAC), with a 30- to 50-fold increased risk compared to the general population.2 Nevertheless, only a small proportion of patients with BO develop OAC; annual incidence is estimated at 0.27%, or 0.61% for a combined risk of high-grade dysplasia and OAC.3,4 For this reason, screening and surveillance programmes for high-risk patients have been implemented in developed countries.5 Some studies have reported a considerable increase in the incidence of OAC over the past 30 years in countries such as the USA.6 This is evidence of both shortcomings in existing screening programmes and the existence of other external factors, apart from BO, involved in the carcinogenic process. Studies have shown obesity and an unhealthy diet to be independent risk factors for OAC, even in the absence of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD).7

Strategies for treating gastro-oesophageal reflux include medical therapy, to inhibit gastric acid secretion, and surgery. Both have been shown to initially improve symptoms, reduce the acid reflux that damages the oesophageal mucosa, and halt the carcinogenic process.4,8,9 Among the drugs available to treat BO, proton pump inhibitors (PPI) have been shown to be the most effective in reducing gastric acid production, controlling GORD symptoms, and increasing mucosal healing in patients with oesophagitis. Acid suppressants are not usually entirely successful in controlling either symptoms or acid secretion, above all in long-segment BO (>3cm), which is more refractory to conventional dosing regimens.10 Evidence suggests that control of symptoms is not always associated with control of acid reflux measured by pH monitoring.11 Some clinical trials have reported a lower incidence of dysplasia and cancer in patients with BO undergoing Nissen fundoplication compared with those receiving medical treatment, although these preliminary findings were not confirmed in later, more methodologically sound studies.12,13

BO is the primary risk factor for OAC, and clinical symptoms do not reflect pH acidity levels, therefore, controlling symptoms such as pyrosis, burning sensation or chest pain is insufficient; acid reflux inhibition should be the primary therapeutic objective in patients with BO.14

The aim of this study was to evaluate acid reflux control in patients with BO in our healthcare catchment area, according to whether they received medical or surgical treatment.

MethodsWe conducted a single-centre, retrospective, descriptive, comparative study in the gastroenterology department of the Leon University Hospital. The records of all patients diagnosed with BO between January 2003 and December 2013 on the basis of endoscopic and histological findings who underwent 24-h ambulatory oesophageal pH monitoring were included in the study.

Patients were selected from the pH monitoring records maintained in our Gastrointestinal Motility Unit. All patients previously diagnosed with BO who had undergone oesophageal pH monitoring to evaluate response to acid reflux management strategies were included.

The pH monitoring was performed by a single specialist and nurse from our Motility Unit. All tests were performed during the morning, following a 10-h fast. On the day of the test, patients were instructed to pursue their normal everyday activities, avoiding physical exertion, and to record on a chart the time spent upright or supine, as well as each episode of reflux, belching or vomiting occurring during the day.

Study patients (n=128) were divided into 2 groups, according to treatment:

- 1.

Medical treatment with PPIs (n=75). PPIs were taken in a single- or double-dose regimen, as prescribed by the patient's physician. In all cases, monitoring was performed at least 1 year after starting PPI treatment. The medication was not suspended during the study, as the objective was to evaluate the extent to which the treatment controlled acid reflux. Standard treatment was defined as a single-dose PPI regimen, and double-dose was defined as 2 doses of PPI per day. The pH monitoring was not only performed due to persistence of symptoms, but also to evaluate response to treatment and/or as a part of the preoperative workup.

- 2.

Surgical treatment: laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication (n=53). This group included patients undergoing pH monitoring 1 year after surgery to evaluate response to treatment. Patients undergoing pH monitoring due to clinical worsening or when monitoring was ordered for reasons other than follow-up less than 1 year after surgery were excluded. None of the surgical patients underwent pH monitoring while also on PPI therapy. In most cases, surgery had been indicated following persistence of symptoms due to lack of response to medical treatment. Surgery was performed to prevent progress of long-segment BO in 19 young patients.

Length of BO as recorded on the endoscopy database was defined as short-segment (less than 3cm) or long-segment (greater than 3cm).

The following 24-h oesophageal pH monitoring parameters were recorded:

- -

Fraction of total time with pH <4, in the supine position and upright, expressed as a percentage.

- -

DeMeester score.

- -

Number of reflux episodes lasting >5min in total, in the upright position and supine.

Reports from all pH monitoring tests were obtained for all BO patients. The patient's motility history was examined to obtain epidemiological information and details of the treatment administered (PPI, dosage) at the time of the test, and the reason the test was requested. Details of the histological diagnosis and length of the BO were extracted from the endoscopy records kept in our department and on the hospital's intranet service. Once all the data had been gathered, epidemiological variables, fraction of total time with pH <4 in both upright and supine position, number of reflux episodes lasting >5min in total in both upright and supine position, and DeMeester score were compared between patients receiving medical treatment with PPIs and surgery (Nissen fundoplication).

Uncontrolled acid reflux, indicating therapeutic failure, was defined as DeMeester score>15 or fraction of total time with pH <4 greater than 5% on the pH monitoring.

Statistical analysis was performed using PASW statistics 18 (SPSS). Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute number and percentage. Quantitative variables are expressed as mean and standard deviation. The Chi-square test was used to compare quantitative variables, and the Student's t or Mann–Whitney U tests were used to evaluate differences between means of quantitative variables. Differences in quantitative variables between patients were compared using the Wilcoxon test. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to measure the strength of association between 2 quantitative variables.

ResultsA total of 128 patients (97 men and 31 women) were included, with a mean age of 49 years. Most (87 patients, 68%) presented short-segment BO. Half of all medical patients followed a standard PPI regimen, and half a double-dose regimen (PPI/12h). The most commonly used PPI (21% of all cases) was lansoprazole.

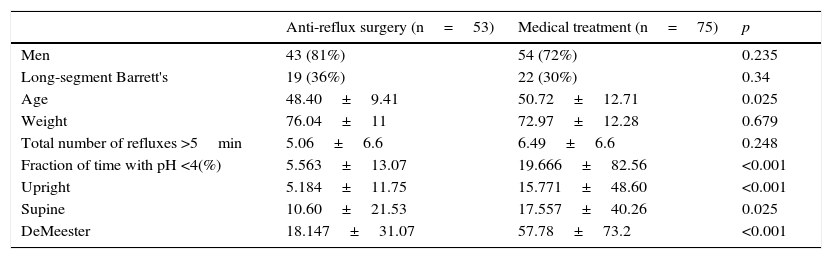

Table 1 compares outcomes in medical and surgical patients. Men outnumbered women in the surgical group and also in the long-segment BO group; 36% of long-segment cases underwent surgery compared with 30% receiving medical treatment. As can be seen, percentage of time with pH <4 and DeMeester scores were significantly lower among patients undergoing surgical treatment. The groups were evenly matched in terms of body weight and time from diagnosis, although age differences were observed between groups, as shown in Table 1.

Patient characteristics by type of treatment received.

| Anti-reflux surgery (n=53) | Medical treatment (n=75) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 43 (81%) | 54 (72%) | 0.235 |

| Long-segment Barrett's | 19 (36%) | 22 (30%) | 0.34 |

| Age | 48.40±9.41 | 50.72±12.71 | 0.025 |

| Weight | 76.04±11 | 72.97±12.28 | 0.679 |

| Total number of refluxes >5min | 5.06±6.6 | 6.49±6.6 | 0.248 |

| Fraction of time with pH <4(%) | 5.563±13.07 | 19.666±82.56 | <0.001 |

| Upright | 5.184±11.75 | 15.771±48.60 | <0.001 |

| Supine | 10.60±21.53 | 17.557±40.26 | 0.025 |

| DeMeester | 18.147±31.07 | 57.78±73.2 | <0.001 |

Data shown as mean±standard deviation.

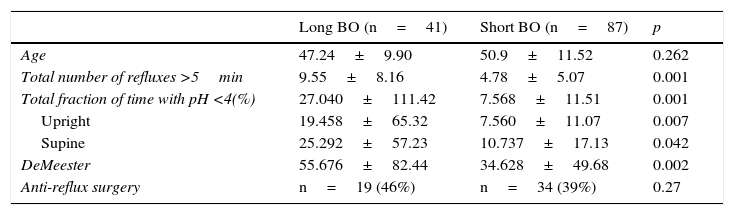

Length of BO was compared between groups (Table 2). Of a total of 41 patients with long-segment BO, 46.3% (n=19) underwent surgery compared with only 39% of the 87 patients (n=34) with short-segment BO. The total number or episodes of reflux lasting <5min, fraction of total time with pH <4, fraction of time upright with pH <4, and DeMeester score were all significantly lower in patients with short-segment BO (p<0.05).

Inter-patient differences by length of Barrett's oesophagus.

| Long BO (n=41) | Short BO (n=87) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47.24±9.90 | 50.9±11.52 | 0.262 |

| Total number of refluxes >5min | 9.55±8.16 | 4.78±5.07 | 0.001 |

| Total fraction of time with pH <4(%) | 27.040±111.42 | 7.568±11.51 | 0.001 |

| Upright | 19.458±65.32 | 7.560±11.07 | 0.007 |

| Supine | 25.292±57.23 | 10.737±17.13 | 0.042 |

| DeMeester | 55.676±82.44 | 34.628±49.68 | 0.002 |

| Anti-reflux surgery | n=19 (46%) | n=34 (39%) | 0.27 |

Data shown as mean±standard deviation.

Overall, 37/128 cases (29%) presented uncontrolled acid reflux. In this regard, a substantial difference was observed between groups: therapeutic failure was observed in up to 40% of patients receiving medical treatment vs only 13% of surgical cases (p<0.001).

In the surgical group (n=53 patients), pH monitoring was performed both before and after the procedure in 19 cases. The 19 patients undergoing pre-surgical pH monitoring were receiving medical treatment, whereas in these same patients, as in the rest of the surgical group, post-surgical monitoring was performed without medication. An analysis of this group showed a significant reduction in all parameters following surgery (p<0.01). Prior to surgery, moreover, acid reflux was controlled in only 37% of these patients, while in the post-surgery studies up to 95% presented good control.

DiscussionAmbulatory oesophageal pH monitoring is the only study that directly measures oesophageal acid exposure. It is indicated in patients with persistent GORD symptoms despite PPI therapy, above all in cases where endoscopy is negative for GORD. It is used to evaluate response to treatment in patients receiving therapy and to confirm diagnosis in patients scheduled for surgery.15 Impedance–pH monitoring, which also measures non-acid reflux, is currently used to obtain a more accurate diagnosis. Indications for surgery are well established: intolerance of medical therapy, lifelong medical treatment ruled out, presence of GORD refractory to optimal medical treatment, reflux associated with large hiatal hernia or morbid obesity with indication for surgery.

Using our patient records, we retrospectively evaluated response to these 2 standard strategies for treating GORD in patients with a histopathological diagnosis of BO. Like earlier authors, such as Helman et al.16 in their retrospective analysis of a cohort of 74 patients undertaken in 2012, we found length of the BO to be directly associated with severity of acid reflux. Therefore, as reported in studies published in 1998, there seems to be a clear association between the BO and the degree and length of acid exposure.17 This same association was found in both treatment groups. Although surgery is usually performed in patients with long-segment BO, our findings echo those of other studies that have shown that surgical treatment of short-segment BO results in improved control of acid reflux and mucosal healing.18 Some authors have suggested that patients with long-segment BO might be unusually resistant to PPIs. Although the underlying mechanism is not fully understood, this could explain the poor response to treatment shown by these patients. Reflux diathesis and delayed gastric emptying have been postulated as possible causes of this apparent resistance to the action of antacid drugs.9

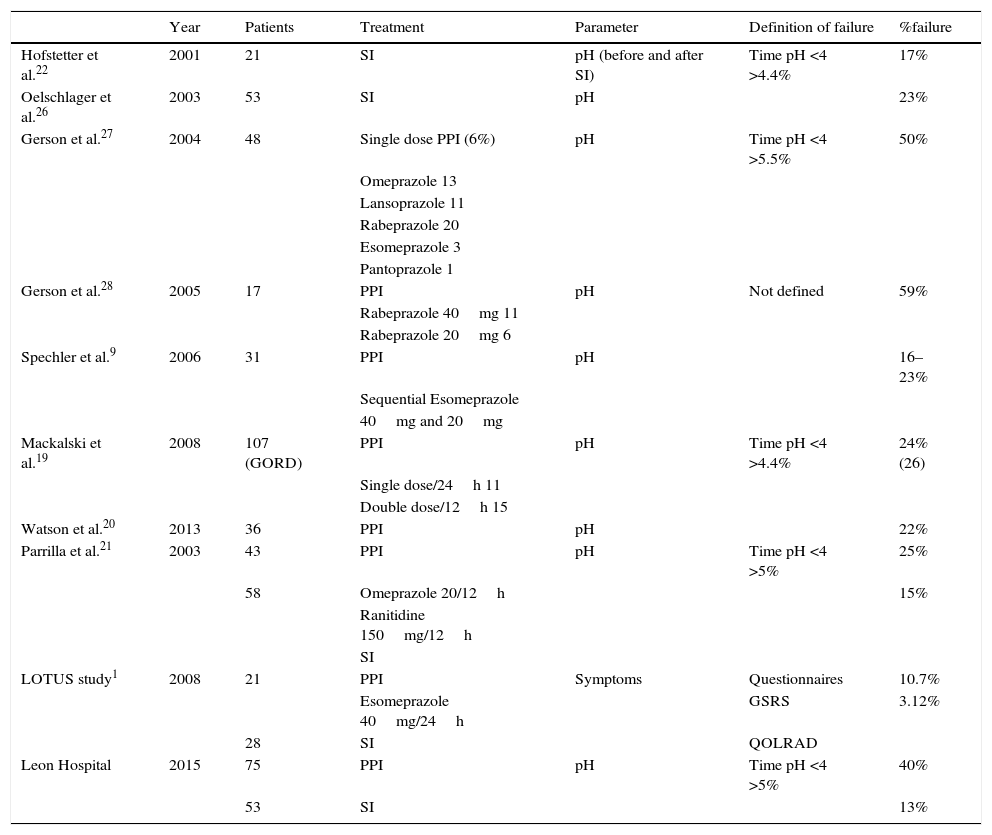

In our experience, neither medical nor surgical treatment is entirely successful in controlling acid reflux measured by pH monitoring. A list of studies published to date (Table 3) shows the failure rate of these strategies. PPIs are the traditional, most widely used therapy in patients with severe to moderate symptoms of GORD. In most series, they are associated with poor control of acid reflux, with failure rates ranging from 20% to 40%. Earlier studies show slightly lower rates, such as the 16.23% failure rate reported by Spechler et al. in 2006. In another series of 107 patients published in 2008, with a similar definition of therapeutic failure to ours, acid reflux remained uncontrolled in 24% of patients.19 These findings are similar to others obtained from a study of 36 patients by Watson et al.,19,20 in which pH control was poor in 22% of patients. In our group, up to 40% of patients presented pathological acid reflux, despite PPIs. One explanation for this is that we collected data retrospectively from patient records in the pH monitoring database, aware of the fact that patients receiving PPIs undergo pH monitoring because of the refractory nature of their symptoms. These patients, therefore, are most likely to present poor acid reflux control. Although the aim of our study was not to analyse prolonged use of PPIs, it is important to note that this therapy has been recommended for the chemoprevention of OAC.4

Principle studies on acid reflux control in BO.

| Year | Patients | Treatment | Parameter | Definition of failure | %failure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hofstetter et al.22 | 2001 | 21 | SI | pH (before and after SI) | Time pH <4 >4.4% | 17% |

| Oelschlager et al.26 | 2003 | 53 | SI | pH | 23% | |

| Gerson et al.27 | 2004 | 48 | Single dose PPI (6%) | pH | Time pH <4 >5.5% | 50% |

| Omeprazole 13 | ||||||

| Lansoprazole 11 | ||||||

| Rabeprazole 20 | ||||||

| Esomeprazole 3 | ||||||

| Pantoprazole 1 | ||||||

| Gerson et al.28 | 2005 | 17 | PPI | pH | Not defined | 59% |

| Rabeprazole 40mg 11 | ||||||

| Rabeprazole 20mg 6 | ||||||

| Spechler et al.9 | 2006 | 31 | PPI | pH | 16–23% | |

| Sequential Esomeprazole | ||||||

| 40mg and 20mg | ||||||

| Mackalski et al.19 | 2008 | 107 (GORD) | PPI | pH | Time pH <4 >4.4% | 24% (26) |

| Single dose/24h 11 | ||||||

| Double dose/12h 15 | ||||||

| Watson et al.20 | 2013 | 36 | PPI | pH | 22% | |

| Parrilla et al.21 | 2003 | 43 | PPI | pH | Time pH <4 >5% | 25% |

| 58 | Omeprazole 20/12h | 15% | ||||

| Ranitidine 150mg/12h | ||||||

| SI | ||||||

| LOTUS study1 | 2008 | 21 | PPI | Symptoms | Questionnaires | 10.7% |

| Esomeprazole 40mg/24h | GSRS | 3.12% | ||||

| 28 | SI | QOLRAD | ||||

| Leon Hospital | 2015 | 75 | PPI | pH | Time pH <4 >5% | 40% |

| 53 | SI | 13% |

GSRS: Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale; PPI: Proton pump inhibitors; QOLRAD: Quality of Life in Reflux and Dyspepsia; SI: Surgical intervention.

Surgery (laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication) is the standard treatment when PPIs fail. This strategy, however, has fallen out of favour in recent years due to the high rate of relapse, which forces patients to fall back on PPIs, with all their associated side effects, the most common of which is dysphagia. This is reflected in our findings; although acid reflux control improved with surgery, post-surgery relapse, though minimal, was nevertheless around 15%. This is similar to the results reported by Parrilla et al.21: postoperative functional studies showed that fundoplication restored the competence of the lower oesophageal sphincter and reduced acid reflux in 85% of the 58 cases analysed. Similar long-term results were found in the LOTUS (2008) study: after 3 years of follow-up, acid reflux control was significantly better following laparoscopic surgery vs PPI therapy (esomeprazole).1Table 3 summarises the results of the most important studies in acid reflux control using either of these 2 therapeutic options, together with the findings from our study.

The outcome is even better when pH monitoring parameters are compared before and after surgical intervention. In the subgroup of 19 patients, 95% presented good acid reflux control (less than 5% of time with pH <4). This is similar to the outcome reported by Hofstetter et al.,22 where a pre- and postoperative analysis of pH levels showed significant improvement in time with pH <4 in 83% of 21 patients analysed.

Our study has a few weak points, perhaps the most important being its retrospective nature, which exposes us to patient selection bias. Moreover, patient selection, being retrospective, was more prone to loss of data, such as diagnosis and the type, regimen and dosage of PPIs in the medical treatment arm. These data would have helped clarify which regimen and dosage of each type of PPI is needed to control acid reflux in BO. We did not evaluate the presence or absence of symptoms when performing pH monitoring, because this information was not noted in our records. This prevented us from evaluating the observations made by other authors, namely, that symptoms do not correlate with objective measurement of pathological acid reflux. Unlike recent studies, we did not evaluate whether surgical treatment facilitated regression of BO and/or dysplasia. The controversy surrounding this issue is illustrated by the systematic review published by Chang et al.,23 who were unable to show that anti-reflux surgery was more successful than medical treatment in preventing OAC, despite reviewing 25 papers. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies, however, and show that surgery is more successful in controlling acid reflux. Nevertheless, the lack of randomisation in our study prevents us from ruling out selection bias, insofar as patients with the severest symptoms are those that receive treatment, and are therefore those that most benefit from surgery.

To conclude, medical treatment must be optimised, compliance with PPI therapy and determination of dosage must be investigated, and response to treatment monitored. Despite the broad range of therapeutic options currently available, acid reflux control in patients with BO is still far from optimal. Fundoplication is the best treatment to control acid reflux; however, it is not without its complications, and effectiveness depends on the level of experience in each hospital. It is important to explain to patients the benefits and drawbacks of each therapeutic approach so that they can share in the decision-making process.

A number of promising surgical and endoscopic techniques, such as transoral fundoplication (EsophyX), are currently being developed for the treatment of GORD and BO.24,25 Further studies are needed to compare long-term outcomes with these and other techniques available today.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Fernández Fernández N, Domínguez Carbajo AB, João Matias D, Rodríguez-Martín L, Aparicio Cabezudo M, Monteserín Ron L, et al. Estudio comparativo del tratamiento médico frente al quirúrgico en el control ácido del esófago de Barrett. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:311–317.