Leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LV) is an uncommon small-vessel vasculitis which can be secondary to several drugs.1 Its association with adalimumab is extremely rare and has been described in only a few reports in the literature.2–4 We report the cases of three patients who developed histologically confirmed leukocytoclastic vasculitis following adalimumab therapy. Discontinuation of the drug led to complete resolution of the cutaneous manifestations in all cases.

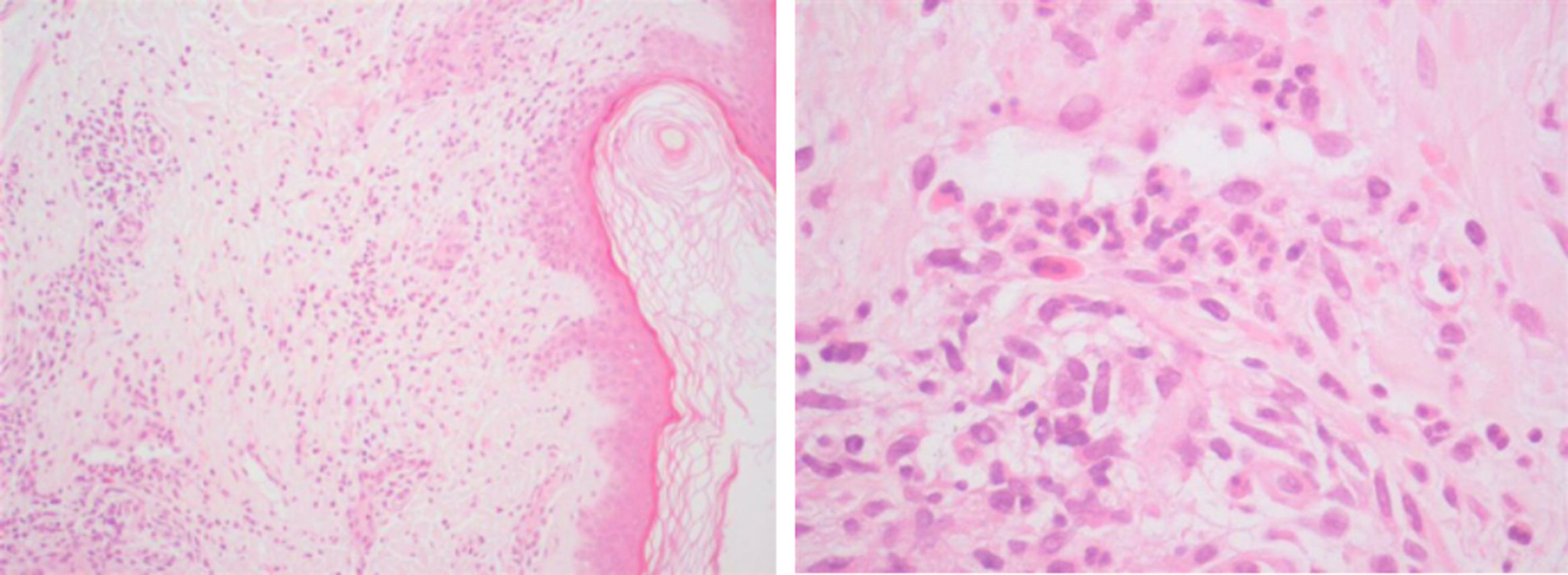

Case 1: A 29-year-old female, diagnosed with colonic Crohn's disease six years earlier, developed palpable purpuric lesions in the lower limbs and trunk approximately sixteen months after adalimumab initiation as monotherapy (Fig. 1A and B). Biopsies were compatible with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. All lesions disappeared in about four weeks following interruption of the anti-TNFalpha. Re-exposure to the drug, four months later, led to recurrence of the vasculitis and forced permanent discontinuation of the treatment.

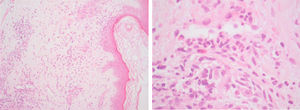

Case 2: A 60-year-old male, nineteen years after the diagnosis of ileocolonic and perianal Crohn's disease, was receiving azathioprine (2.5mg/kg/day) for almost ten years when adalimumab was started. After fourteen months of combination therapy the patient presented with an one-month history of palpable purpura in the lower limbs which was histopathologically characterized as leukocytoclastic vasculitis (Fig. 2) and completely resolved with the withdrawal of the biological agent.

Case 3: A 44-year-old female, diagnosed with colonic and perianal Crohn's disease twentytwo years before, also treated with azathioprine (2mg/kg/day), underwent biological treatment with adalimumab. Six years later, she was admitted due to palpable purpura in the lower limbs for the last three weeks, whose biopsies were compatible with leukocytoclastic vasculitis. Adalimumab was discontinued and complete resolution of the lesions was observed within two weeks. Three months later, given the unusually long latency period, raising doubts regarding the causality between the agent and the appearance of vasculitis, reintroduction of the drug was attempted. However, rapid and severe recurrence of the purpuric lesions occurred, leading to definitive withdrawal of the therapy (Fig. 1C).

All patients were in clinical remission while receiving maintenance treatment with adalimumab (40mg, every other week). Moreover, they were all previously exposed to infliximab, which was suspended due to primary non-response in the first female patient and due to a serious infusion reaction – without dermatological manifestations – in the remaining.

The time between infliximab discontinuation to adalimumab initiation was 5 years (case 1), 9 years (case 2) and 10 months (case 3). With the exception of elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, laboratory evaluation – including human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus screening, autoimmune panel, search for cryoglobulins, serum protein electrophoresis and urinalysis – was unremarkable, allowing exclusion of alternative conditions and other organ involvement. In the three cases, skin biopsies showed perivascular damage and infiltration by polymorphonuclear cells, nuclear debris and fibrinoid necrosis, with also a few eosinophils (Fig. 2). Interruption of the culprit drug was sufficient to allow total recovery of the vasculitis within two to four weeks, without the need for any additional pharmacological intervention in any case. No recurrences occurred after definitive suspension of the anti-TNFalpha agent.

The development of skin complications is well-recognized in patients with inflammatory bowel disease, either in association with the disease itself or as a treatment-related adverse event.2–6 Ramos-Casals and colleagues identified 113 published cases of anti-TNFalpha associated vasculitis – including leukocytoclastic vasculitis – in a 13 year-period, with only 4% of them (n=5) arising in subjects receiving adalimumab.6 Although the pathophysiological mechanisms are not fully understood yet, it is postulated that those patients may undergo immunocomplex deposition and antiTNFalpha-induced apoptosis, followed by perivascular antigen accumulation and subsequent antibody formation, leading to progressive small-vessel damage.7,8 The fact that adalimumab is a fully humanized anti-TNFalpha antibody may justify the lower frequency of such complications when compared to infliximab. Interestingly, our three patients were treated with infliximab for a short period in the past, with two of them having developed severe infusion reactions. It is also worth noting that two of the patients were in combination therapy with azathioprine, which theoretically could further decrease the immunogenic potential of adalimumab and reduce the risk of those events. The time from drug introduction to onset of such hypersensitivity type III reactions is extremely variable, ranging from a few days to several years.7 Symptoms usually resolve in a few weeks with drug discontinuation; however, in refractory patients or in those with systemic involvement, treatment with colchicine, steroids or other immunosuppressants may be required.3,4 Despite some authors having reported the use of a different anti-TNFalpha blocker in patients who developed TNFalpha inhibitor-induced vasculitis, the risk of relapse is a major concern and may influence future treatment options.9 Thus, even in patients like ours, who attained complete remission without any specific therapy, the occurrence of these highly unusual but potentially serious conditions may represent a challenge for the management of the inflammatory bowel disease.

Conflicts of interestAuthors declare no conflicts of interest for this article.