Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) is a form of functional renal failure secondary to splanchnic vasodilation and intense renal vasoconstriction in people with advanced liver disease. Due to its high mortality rate, it is an indication for liver transplantation. Various splanchnic vasoconstrictors are used as a bridge-to-transplantation, with terlipressin being the most studied.

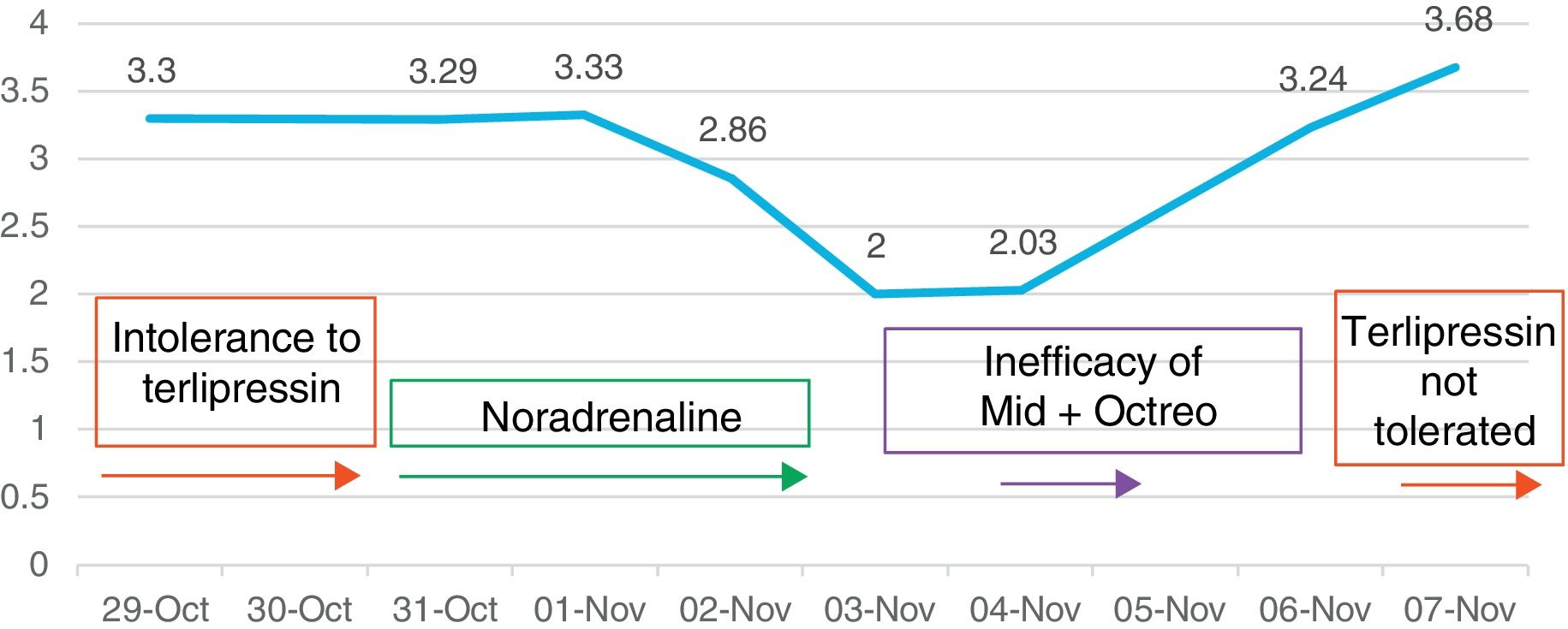

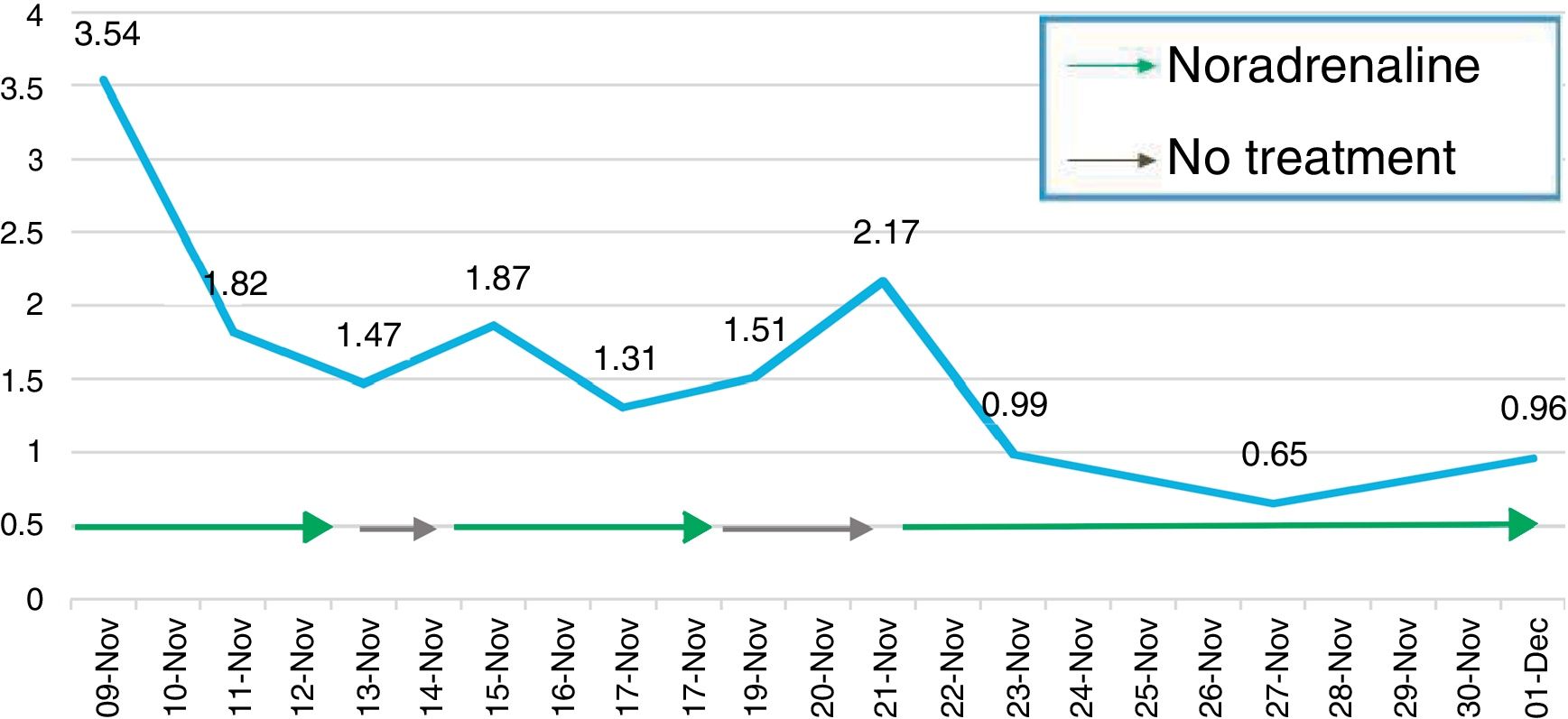

We report the case of a 62-year-old female with alcoholic liver cirrhosis, who was admitted in October 2014 with ascites and kidney failure after a slow post-operative recovery following an umbilical hernia (Child-Pugh B9, MELD 25). After ruling out other causes, type 1 HRS was diagnosed, with creatinine levels of 3.59mg/dl, having had a baseline value of 0.65mg/dl. The patient's ascitic fluid showed no signs of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) and treatment with intravenous albumin and terlipressin (1mg every 4h i.v.) was initiated. However, the onset of diarrhoea and abdominal cramps led to the withdrawal thereof after two attempts on consecutive days. Later, with creatinine levels of 3.29mg/dl, treatment and monitoring was initiated with albumin (1g/kg on the first day, then 40g every 2h) and a continuous intravenous noradrenaline perfusion. The starting dose was 0.3mg/h (0.1μg/kg/min) and this was adjusted based on the patient's blood pressure and diuresis, with the aim of increasing her mean blood pressure by at least 10mmHg, for which she required a maximum dose of 0.9mg/h. Her response was favourable and after three days, following a 36% reduction in creatinine levels (2.0mg/dl), the perfusion was suspended and oral midodrine (7.5mg every 8h) and subcutaneous octreotide (100μg every 8h) initiated alongside albumin, with a view to her continuing treatment on an outpatient basis. However, these drugs were suspended three days later due to inefficacy (creatinine 3.24mg/dl). Treatment with terlipressin was resumed and withdrawn once more due to intolerance (Fig. 1). Noradrenaline was then reintroduced, being the only treatment to demonstrate good tolerability and efficacy. It was withdrawn due to a complete response after four days (creatinine<1.5mg/dl), with no side effects, and resumed on two subsequent occasions due to relapse, for 5 and 10 days, until a creatinine value of 0.96mg/dl was obtained (Fig. 2). Ten days after being suspended for the last time, the patient was discharged with creatinine levels of 0.70mg/dl. Two months later, she received a liver transplant.

HRS is the third most common cause of deteriorating renal function in patients with cirrhosis and ascites (20%), behind prerenal failure (48%) and acute tubular necrosis (32%).1 In type 1 HRS, this decline is fast, generally occurring after a precipitating factor, which in our case was the patient's slow post-operative recovery following an umbilical hernia. From a physiological and pathological point of view, in cirrhotic patients, splanchnic vasodilation, the activation of compensatory vasoconstrictors and a decline in heart function are all conducive to developing the condition. The treatment of choice is liver transplantation, owing to its high mortality rate. Splanchnic vasoconstrictors increase the number of patients who survive while awaiting transplantation and also improve their prognosis thereafter.2 In Europe, the most widely-used vasoconstrictor is terlipressin, the efficacy of which has been proven in placebo-controlled studies.3 However, it is not available in many countries. Among others, diarrhoea and abdominal cramps are commonly described side effects which make it difficult to tolerate. At present, however, there is a controlled study published in 2016, where terlipressin given by continuous infusion was better tolerated at lower doses than those required in boluses.4

Alpha-adrenergic drugs (noradrenaline, midodrine) constitute an alternative treatment if terlipressin is not available or in cases such as ours, due to intolerance or inefficacy. Noradrenaline is available worldwide and is cheaper than terlipressin. Its efficacy in type 1 HRS was studied for the first time in 2002. Three studies have been carried out to compare the efficacy of noradrenaline versus terlipressin in type 1 HRS, along with one other in type 2 HRS. However, no strategy has proven superior.5–8 There are no controlled, vasoconstrictor-free studies assessing the efficacy of noradrenaline. The drug has been linked to fewer adverse effects, primarily due to the frequency with which patients treated with terlipressin suffer abdominal symptoms.5,6 From a cardiovascular point of view, they have been shown to be equally safe. Patients treated with noradrenaline seem to present a milder decline in their MELD score than those treated with terlipressin, due to a supposed deterioration in liver function as a result of decreasing hepatic blood flow, without significant hepatic ischaemia being observed.6

All of the studies make reference to terlipressin's higher cost.9 Only one found this strategy to be cheaper, having considered not only the price of the drug but also the cost associated with patients staying at specialist units, which noradrenaline requires.10

In conclusion, noradrenaline is a safe and effective alternative in the treatment of type 1 HRS. It is also more widely available and has fewer adverse effects. More studies are needed to clarify whether or not the added cost of administering noradrenaline at intensive care units makes the strategy the most cost-effective.

Please cite this article as: Sendra C, Silva Ruiz MP, Ferrer Rios MT, Alarcón García JC, Pascasio Acevedo JM. La noradrenalina como tratamiento médico alternativo a la terlipresina en el manejo del síndrome hepatorrenal tipo 1. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:440–441.