Faecal calprotectin is a useful technique for detecting activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. However, there may be high levels due to factors other than the activity of ulcerative colitis. Our aim was to analyse possible false positive results of calprotectin for the activity of ulcerative colitis owing to the presence of inflammatory polyps.

Patients and methodsRetrospective, observational, descriptive study. Data was collected from patients monitored for 2 years in whom a colonoscopy had been requested within 3 months after detecting high calprotectin values (>150 μg/g) and before modifying the treatment.

ResultsWe reviewed 39 patients and in 5 of them, with previous diagnosis of extensive ulcerative colitis, inflammatory polyps were detected. Three patients were on treatment with mesalazine, one with azathioprine and another with infliximab. All of them were asymptomatic and the endoscopy showed no macroscopic activity (endoscopic Mayo score = 0) or histological activity. The median values for calprotectin were 422 μg/g (IQR: 298-2408) and they remained elevated in a second measurement. In 4 of the patients, the inflammatory polyps were multiple and small in size. The other patient had a polyp measuring 4 cm.

DiscussionIn clinical practice we can find high faecal calprotectin levels not due to the presence of ulcerative colitis activity, but to other lesions, such as inflammatory polyps. This fact must be taken into account before carrying out relevant changes such as step-up therapy to immunosuppressive drugs or biological drugs in patients with confirmed high calprotectin levels.

La calprotectina en heces es una técnica útil para detectar actividad en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa. No obstante, puede haber valores elevados debido a otros factores distintos de la actividad de la colitis ulcerosa. Nuestro objetivo fue analizar posibles resultados falsos positivos de calprotectina para la actividad de la colitis ulcerosa debidos a la presencia de pólipos inflamatorios.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo, descriptivo y observacional. Se recogieron los datos de pacientes seguidos durante 2 años en los que se realizó una colonoscopia dentro de los 3 meses posteriores a detectarse valores de calprotectina elevados (>150 µg/g) antes de modificar el tratamiento.

ResultadosSe revisaron 39 pacientes y en 5 de ellos, previamente diagnosticados de colitis ulcerosa extensa, se detectaron pólipos inflamatorios. Tres pacientes tomaban mesalazina, 1 azatioprina y otro en tratamiento con infliximab. Todos ellos se encontraban asintomáticos y la endoscopia no presentaba actividad macroscópica (Mayo endoscópico = 0) ni histológica. La mediana de los valores de calprotectina fue: 422 µg/g (RIQ: 298-2408) y permanecieron elevados en una segunda determinación. En 4 de los pacientes los pólipos inflamatorios eran múltiples y de pequeño tamaño. Otro paciente presentaba un pólipo de 4 cm.

DiscusiónEn la práctica clínica podemos encontrar valores de calprotectina fecal elevados no debidos a la presencia de actividad de la colitis ulcerosa sino a otras lesiones como pólipos inflamatorios. Este hecho debe ser tenido en cuenta antes de llevar a cabo cambios relevantes como la subida de escalón terapéutico a inmunosupresores o biológicos en pacientes con elevación de calprotectina confirmada.

Faecal calprotectin (FC) is a useful biomarker for monitoring patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), in order to predict the risk of relapse,1 define patients who might benefit from further exploratory tests2 and identify those in both clinical and biological remission.3

Calprotectin is the principal cytosolic protein in neutrophils. It can also be found to a lesser degree in activated monocytes and macrophages. It is released in very early phases of the inflammatory process and its faecal concentration is directly proportional to the presence of neutrophils in the intestinal lumen.4 Calprotectin is resistant to being broken down by bacteria and is stable for days at room temperature, making it suitable for use in clinical practice.5

FC is useful for differentiating between inflammatory and functional processes,6 and, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), FC values correlate with endoscopic activity and clinical and endoscopic response to treatment, and so have a short-term prognostic value. However, raised FC is not specific to IBD. FC can be elevated in other conditions, including gastrointestinal tract tumours, coeliac disease, acute infections (such as diarrhoea of bacterial origin), diverticular disease, polyps, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)-induced gastrointestinal disorders and microscopic colitis.5,7–9

Moreover, we need to be aware that in some patients with IBD the gastrointestinal symptoms do not reflect what is really going on. It has been reported that over a third of patients in clinical remission (and thus asymptomatic) have endoscopic lesions. Meanwhile, at the other extreme, over 10% of patients with symptoms have a normal endoscopy.10,11 In this situation, FC has become an additional tool for detecting activity in the management and follow-up of patients with IBD, and it is important for us to know its strengths and weaknesses. Determination of FC at periodic follow-up appointments can help detect patients at risk of relapse, but we must be aware that positive results can be caused by factors other than UC activity. This is important, as the results could lead to inappropriate changes being made to a patient's therapy.

One of the conditions which can cause elevations in FC levels is polypoid lesions such as adenomas or juvenile polyps.12–15 Inflammatory polyps are relatively common findings in patients with IBD,16 being more common in UC than in Crohn's disease. Polypoid lesions can be divided into the following categories: pseudopolyps, inflammatory polyps, and post-inflammatory polyps. These terms are used interchangeably in the literature, which leads to a certain degree of confusion.17 The term pseudopolyps is applied to persistent mucosa islets which develop between ulcers in a severe flare-up of IBD, creating the impression of a polyp.18 Inflammatory polyps are produced when more intense granulation tissue is formed in some focal areas during the inflammatory process.19 Last of all, during the healing process there may be excessive re-epithelialisation and regeneration, forming post-inflammatory polyps,20 whose shape is related to the effect of peristaltic contractions and the passage of faeces, causing lengthening of the mucosal flaps.21 Kelly and Gabos divided inflammatory polyps into flaps of polypoid mucosa and mature inflammatory polyps, covering all the above forms, and proposed the term inflammatory polyp as the most appropriate for general use,22 and this is the term that we shall use in our description.

Some authors have reported double the prevalence of polyps in UC compared to Crohn's disease of the colon.23 Reported prevalence rates vary from 4% to 74%, but most of the data supporting these findings were obtained from older studies that considered only UC. The most frequently reported incidence rates in UC are within the range of 10% to 20%.24–26 This type of polyp, found in one in every 5–10 patients with UC, could affect the results of the FC tests we perform during follow-up of patients in clinical remission, and this formed our working hypothesis. Our aim was therefore to analyse FC results which were possibly false positive for UC activity due to the presence of inflammatory polyps.

MethodsRetrospective, observational descriptive study in patients with UC followed up in our IBD unit for 2 years (from October 2016 to September 2018), who had a colonoscopy within 3 months of the detection of high FC values before any change was made to their treatment. We established an FC value of 150 μg/g as cut-off point for the existence of UC clinical activity.5 Patients with gastrointestinal symptoms at the time of the FC determination, patients with other gastrointestinal disorders or patients who had taken NSAIDs in the month prior to the FC test according to the information collected from the medical records were all excluded.

We studied patients whose only endoscopic finding was the presence of inflammatory polyps with no other lesions (Mayo endoscopic score = 0). Demographic variables such as gender and age, extent of the disease using the Montreal classification, treatment at the time of the FC determination, patient's clinical status according to the Mayo Score and endoscopy were collected by reviewing the hospital's computerised medical records. FC was measured by the Thermo Fisher EliA™ fluorescence enzyme immunoassay method.

For the statistical analysis, categorical variables were expressed through frequencies and percentages. For quantitative variables, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was first performed to assess normality and the data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation if the variable followed a normal distribution, or median and interquartile range if not.

The study protocol was approved by our hospital's ethics committee.

ResultsWe reviewed the medical records of 150 patients with UC who had initially had FC determined for monitoring and who attended a scheduled appointment for follow-up of their disease. In 39 cases, results were available for a colonoscopy performed within 3 months after the test to measure FC. Out of these, we identified 5 patients (12% of the patients with high FC values and colonoscopy immediately after) in whom the endoscopy showed no macroscopic activity (Mayo Score = 0) or histological activity (no neutrophils in the colon mucosa biopsies), but did show lesions compatible with inflammatory polyps, subsequently confirmed by biopsy. All five patients had previously been diagnosed with extensive UC; their mean age was 39 ± 15 years and 60% were male. The 5 patients had their FC measured a second time, a median of 37 ± 6 days since the first determination.

In the rest of the cases (n = 34) some degree of endoscopic activity (Mayo Score ≥ 1) and histological activity (mild or moderate according to the pathologist) was detected. The clinical decision was made in 61.7% of the cases (n = 21) to increase the maintenance dose of oral 5-aminosalicylates and/or add topical therapy. No immediate treatment changes were made in the remaining cases, all of which were asymptomatic, with only mild disease (Mayo Endoscopic Score = 1).

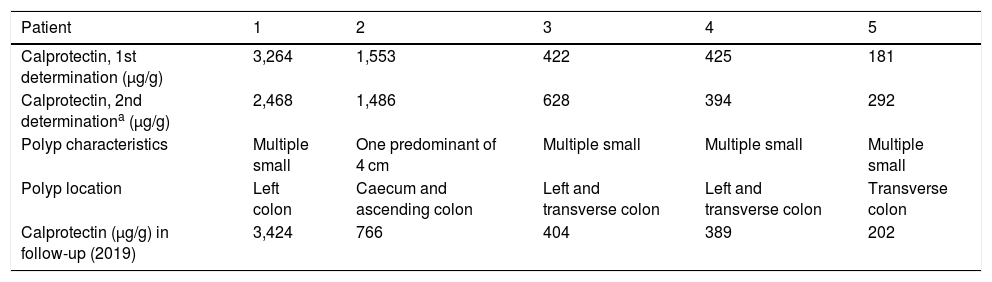

The five patients with inflammatory polyps were on treatment for their UC when they were found to have high FC, three of them with oral mesalazine (60%), one with azathioprine (20%) and the other, anti-TNF biological therapy with infliximab (20%). None of these 5 patients were on treatment with NSAID or proton-pump inhibitors. All of the patients were clinically asymptomatic at the time of the FC determination (partial Mayo Score = 0); the median of the FC values was 422 μg/g (interquartilerange 298–2408) and they remained high in the second test. The individual FC values and the characteristics and location of the inflammatory polyps are shown in Table 1, which also shows the FC values from the subsequent follow-up of patients (tests performed over the course of 2019), which in all cases remained >150 μg/g. Four of the patients had multiple small polyps. The fifth patient had an inflammatory polyp 4 cm in size in the right colon. The presence of inflammatory polyps had been described in prior colonoscopies in 4 cases, with previous data, but we did not have prior FC determinations as use of the technique did not become routine in our hospital's laboratory department until after these investigations. No treatment changes were made in these 5 patients.

Faecal calprotectin determinations, and characteristics and location of inflammatory polyps in our patients.

| Patient | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calprotectin, 1st determination (µg/g) | 3,264 | 1,553 | 422 | 425 | 181 |

| Calprotectin, 2nd determinationa (µg/g) | 2,468 | 1,486 | 628 | 394 | 292 |

| Polyp characteristics | Multiple small | One predominant of 4 cm | Multiple small | Multiple small | Multiple small |

| Polyp location | Left colon | Caecum and ascending colon | Left and transverse colon | Left and transverse colon | Transverse colon |

| Calprotectin (µg/g) in follow-up (2019) | 3,424 | 766 | 404 | 389 | 202 |

Inflammatory polyps are known local complications in patients with IBD.27 They are usually asymptomatic but can sometimes cause bleeding or obstruction.17,22 These lesions can have a variety of forms, including sessile, pedunculated or mucous bridges, and can be single or multiple, as in our patients, and diffuse or localised.17,18 They also vary in size, but are usually short. When larger than 1.5 cm, they tend to be called giant pseudopolyps28 (one case in our series). The clinical importance of polyps is uncertain, apart from their relationship with an intermediate risk of colorectal cancer, for which screening guidelines recommend a colonoscopy at two or three-year intervals.29,30 It is generally accepted that if these lesions are properly examined using endoscopic criteria and do not cause complications, they need not be removed.31 Inflammatory polyps are not included in the endoscopic indices for monitoring UC activity.

FC is a highly reliable biomarker for detecting endoscopic activity in UC.5,32,33 The optimal cut-off point for FC to distinguish endoscopic remission (Mayo Endoscopic Score ≤ 1) has been set at 250 μg/g for the ELISA technique, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.92. This means accepting not only completely normal mucosa, but also the presence of slight changes without erosions or spontaneous bleeding, as endoscopic remission (Mayo Endoscopic Subscores = 0 or 1). With this definition of endoscopic remission, the most suitable cut-off point would be 250 g/g.34,35 However, if we consider a stricter definition of remission, defining as such the complete normalisation of the mucosa (Mayo Endoscopic Subscore = 0), the cut-off point would be lower. Although there is less evidence available on this aspect, a cut-off point of between 100 and 150 μg/g has shown good diagnostic accuracy35,36; values <150 μg/g are associated with the absence of mucosal lesions in endoscopy (Mayo Endoscopic Subscore = 0) and no acute histological lesions in biopsies.5 In our study we therefore used 150 μg/g as the cut-off point.

With respect to the presence of activity and the associated risk of relapse during patient follow-up, in a study conducted in our area with an FC cut-off point of 150 μg/g, clinical relapse in the following 12 months was predicted with a sensitivity of 69% and a specificity of 69%.37 Using the same cut-off point, Costa et al. reported that patients with an FC > 150 μg/g had a 14-fold higher risk of relapse in the following 12 months.38

In patients in remission, serial FC determinations have a greater prognostic value than a single, isolated measurement. Results repeatedly <150 μg/g mean that relapse within the following 3 months is unlikely, while a rise in FC can be detected 3–6 months before a relapse becomes evident.39,40 Any decision based on the FC results should not be made on the basis of one single determination, but consistent serial determinations (at least 2), to increase the accuracy of the test. The recommendations of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] on the use of FC include serial testing in the event of an item of data that does not correspond with the patient's clinical status or a recent colonoscopy. FC can be elevated by other intestinal disorders or for reasons unconnected to intestinal activity, such as taking NSAIDs.5 In the case of our patients, NSAIDs were not an issue as they are advised to try to avoid the use of NSAIDs when they are diagnosed with UC, and they receive written instructions, which include not taking NSAIDs in the two weeks prior to the collection of the sample.

Clinical decisions in a patient with confirmed high FC values can vary from supposedly simple treatment changes, such as increasing the maintenance dose of 5-aminosalicylates or adding or modifying the dose of a topical therapy with mesalazine, to performing endoscopic or radiological tests in a patient who may be asymptomatic, but in whom we are planning a proactive approach which could lead to a major change in treatment (therapy step-up to immunosuppressive or biological agents). Our results highlight the need to perform endoscopic tests in cases where a major treatment change is being considered, as we can find positive FC results caused by other conditions, such as inflammatory polyps, in patients with no UC activity (12% of UC with elevated FC and colonoscopy in our series). Moreover, during the subsequent follow-up of our patients, all their FC values remained >150 μg/g, showing that FC is probably not useful as a biomarker for monitoring UC activity in the follow-up of patients with UC and inflammatory polyps.

Our study has certain limitations, such as the limited number of patients included with colonoscopy after finding high FC levels and not having an endoscopic study in all patients with high FC (in some patients the maintenance dose of 5-aminosalicylates was increased without performing an endoscopic study; in others, a wait-and-see approach was taken with monitoring), so we cannot determine exactly how common it is to have elevated FC due to inflammatory polyps.

We can conclude that in clinical practice, patients with no UC activity can have positive FC results due to other causes, such as inflammatory polyps. This must be taken into account for the adequate management of patients with UC and elevation of FC confirmed by at least 2 determinations. It would be advisable to corroborate the existence of activity in these patients before considering major treatment decisions such as a therapy step-up to immunosuppressive or biological drugs.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Bermejo F, Algaba A, Bonillo D, Jiménez L, Guardiola-Arévalo A, Pacheco M, et al. Limitaciones de la determinación de calprotectina fecal en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa y pólipos inflamatorios. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:73–78.