Intra-abdominal septic complications (IASC) affect short-term outcomes after surgery for colon cancer. Blood transfusions have been associated with worse short-term results. The role of IASC and blood transfusions on long-term oncologic results is still debated. This study aims to assess the impact of these two variables on survival after curative colon cancer resection.

Patients and methodsRetrospective analysis of a prospectively maintained database of patients who underwent curative surgery for colon cancer at a university hospital, between 1993 and 2010. Cox regression was used to identify the role of IASC and transfusions (alone and combined) on local recurrence (LR), disease-free survival (DFS), and cancer-specific survival (CSS).

ResultsOut of the 1686 patients analyzed, 1277 fit in the inclusion criteria. Colorectal surgeons performed the procedure in 82.2% of the patients. Blood transfusions were administered to 25.8% of the patients. Thirty-day complication and mortality rates were 34.5% and 6.1%. IASC occurred in 9.9%. The mean follow-up was 66 months. The 5-year rates of LR, DFS, and CSS were 7%, 79.8%, and 85.1%. The year of surgery and pT (Hazard ratio 9.35, 95% CI 1.23–70.9, for T4) and pN (Hazard ratio 2.57, 95% CI 1.39–4.72, for N2) stages were independent risk factors for LR. The same variables, bowel obstruction and surgeries performed by surgeons not specialized in colorectal surgery, were also associated with worse DFS and CSS. IASC and blood transfusions were not associated with LR, DFS, and CSS, whether alone or combined.

ConclusionsIASC and transfusions were not associated with worse oncological outcomes after curative colon cancer surgery per se. Other factors were more important predictors of survival.

Las complicaciones sépticas intra-abdominales(CSIA) empeoran los resultados a corto plazo después de cirugía por cáncer de colon. Las trasfusiones de sangre también han sido relacionadas con peores resultados a corto plazo. El impacto de la CSIA y de las transfusiones en los resultados oncológicos es todavía debatido. Objetivo del presente estudio fue valorar el impacto de estas dos variables en la supervivencia de pacientes intervenidos por cáncer de colon.

Pacientes y métodosAnálisis retrospectivo de una base prospectiva de pacientes sometidos a cirugía curativa por cáncer de colon en un hospital universitario(1993-2010). Se utilizó regresión de Cox para valorar el efecto de CSIA y trasfusiones(aislados o en combinación) sobre recidiva local(RL), supervivencia libre de enfermedad(SLE) y supervivencia cáncer-especifica(SCE).

ResultadosDe los 1686 pacientes analizados, se incluyeron 1277. La cirugía fue realizada por cirujanos colorrectales en el 82,2% de los pacientes. El 25,8% recibió transfusiones. Las tasas de complicaciones y mortalidad a los 30 días fueron del 34,5% y 6,1%. La frecuencia de CSIA fue del 9,9%. El seguimiento mediano fue de 66 meses. Las tasas a los 5 años de RL,SLE y SCE fueron 7%, 79,8% y 85,1%. El año de tratamiento, los estadios pT(Cociente de riesgo 9,35,IC95% 1,23-70,9,en T4)y pN(Cociente de riesgo 2,57,IC95% 1,39-4,72,en N2)resultaron como factores de riesgo para RL. Las mismas variables, la obstrucción intestinal y la cirugía realizada por cirujanos no colorrectales se asociaron también a peor SLE y SCE. CSIA y trasfusiones no resultaron asociadas con RL, SLE y SCE, ni de forma aislada ni combinadas.

ConclusionesLas CSIA y trasfusiones no afectaron per se los resultados oncológicos de la cirugía de cáncer de colon. Otros factores resultaron más importantes predictores de supervivencia.

Post-operative complications have a negative impact on short-term results of colorectal surgery,1,2 but they have been also associated with tumor recurrence and reduced survival.3 It has been suggested that major complications reduce the overall survival, but do not affect cancer recurrence.4

Anastomotic leaks (AL) are one of the most serious complications in colorectal surgery, because they cause high post-operative morbidity and mortality.5–7 The relevance of AL after colon cancer resection in terms of long-term oncological results is still debated.5,8–11 According to some authors, AL are associated with high rates of cancer recurrence.8,10–12 AL might delay postoperative treatments and increase the probability of developing metastasis,13 reducing disease-free and overall survival.5,8,11,14 However, contradictory findings are reported, and authors failed to demonstrate any effects of AL on oncological results.9

Apart from AL, several adverse events can occur after colon cancer surgery, and many perioperative variables might influence long-term outcomes. Among them, a potential role for perioperative blood transfusions (BT) has been postulated.15,16 In some cases, it is common practice to transfuse patients with severe anemia before surgery. It has been suggested that perioperative BT might increase the incidence of infectious complications after abdominal surgery,17 but their effects on tumor recurrence and long-term survival is still debated.15 Several retrospective series,18 prospective studies19,20 and meta-analyses16,21 found an increased risk for worse oncological outcomes after BT or septic complications, but the findings could have been influenced by confounding factors (e.g. residual tumor or the local dissemination of cancer cells).22 It has also been hypothesized that the combination of these two events increases cancer recurrence and shortens overall survival,23 whereas BT per se may not impair the long-term prognosis after colon cancer surgery.23,24 Therefore, a consensus has not been reached yet.

The aim of this study was to assess the impact of post-operative intra-abdominal septic complications (IASC) and perioperative BT on oncological results after curative colorectal cancer resection.

Material and methodsThis is a retrospective, Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement25-compliant (Suppl. Table 1), observational study. Data on all patients with colon cancer treated by a Colorectal Multidisciplinary Team (MDT) were gathered from the prospectively maintained database of a tertiary hospital. Data were collected ensuring confidentiality and anonymity of patients. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the hospital.

Inclusion and exclusion criteriaAll patients undergoing surgery with curative intent in both urgent and elective settings for primary tumors of the colon and rectosigmoid junction between January 1993 and December 2010 were considered for inclusion.

Patients were excluded if they had (1) other-than-adenocarcinoma malignancies, (2) metachronous cancers, (3) unresectable tumors, if they (4) received palliative treatments, (5) were lost at follow-up, or (6) presented metastatic disease. All the patients included in the study were discussed at a dedicated MDT. An algorithm for patient inclusion is provided in Supplementary Fig. 1.

Pathways of treatment and definitionsBaseline variables on patients, surgical procedure performed, and pathology were prospective collected.

All elective resections were performed or supervised by colorectal surgeons. Urgent procedures were carried out by the on-call team, consisting of general surgeons and/or colorectal surgeons. Oncological resection of colon cancer was performed following described techniques26,27 and the extent of resection was based on tumor location and lymphatic and vascular drainage. Surgical specimens were assessed by pathologists with expertise in colorectal cancer.

Perioperative complications were collected and graded according to Clavien-Dindo classification.28 IASC were defined as AL and intra-abdominal abscesses developed after surgery. Perioperative BT were defined as transfusion of red blood cells during hospital stay. BT were used at discretion of the surgeon and/or anesthetist in charge.

After treatment, patients were followed-up every three months during the first year, every 6 months during the second year, and yearly subsequently. Postoperative assessment included clinical examination, imaging tests, and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) measurement. Recurrence was defined as the presence of tumor cells/tissue, at the site of surgery (local recurrence, LR) or other locations after curative surgery. LRs included those occurring at the site of anastomosis in the area of previous cancer, those in the lymphatic drainage region or in adjacent organs/structures, and peritoneal carcinomatosis. Disease-free survival (DFS) was defined as no evidence of distant disease recurrence during follow-up. Cancer-specific survival (CSS) was defined as absence of death directly caused by tumor progression or recurrence.

Main outcomesAim of this study was to assess the rates of LR, DFS and CSS after IASC and/or BT, and the risk associated with them after curative colon cancer resections.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed with Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22.0.0 (IBM SPSS statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). The probability of 5-year LR, DFS, and CSS were analyzed with Kaplan–Meier curves. In order to evaluate the independent association between IASC and/or BT and oncological results (LR, DFS and CSS), we performed a univariate analysis to identify additional factors to be included in a multivariate Cox regression model. The latter included IASC, BT and variables which influenced oncological results with value of p<0.01 at univariate analysis. We discarded redundant variables and forced inclusion of clinically relevant factors if based on scientific evidence of a significant impact on oncological results.

The risk was reported as Hazard Ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) HR>1 is associated with increased risk of local or distant recurrence, and cancer-related mortality. p values<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

ResultsAfter applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, out of a total of 1686 patients with cancer of the colon and rectosigmoid junction, 1277 were operated on with curative intent and were included in the study (Supplementary Fig. 1). At diagnosis, 18% had bowel obstruction and 8.7% had spontaneous perforation. The majority of procedures were elective and only 23.1%, were urgent. Preoperative data are detailed in Table 1. Almost all procedures (82.2%) were performed by colorectal surgeons. Some 50% of tumors were stage II, followed by stage III (39.1%), and stage I (19.1%). Postoperative chemotherapy was given to 439 patients (34.4%). Surgical and pathological data are detailed in Table 2.

Characteristics of patients (n=1277).

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, yr (mean± SD) | 70.2±11.4 |

| Female gender | 627 (49.1) |

| ASA grade | |

| I | 90 (7) |

| II | 459 (35.9) |

| III | 416 (32.6) |

| IV | 67 (5.2) |

| Not assessed | 245 (19.2) |

| Arterial hypertension | 133 (10.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 72 (5.6) |

| CEA | |

| ≤5ng/ml | 796 (62.3) |

| High>5ng/ml | 301 (23.6) |

| Not assessed | 180 (14.1) |

| Tumor location | |

| Right | 433 (33.9) |

| Transverse | 95 (7.4) |

| Left | 749 (58.7) |

| Stage | |

| I | 244 (19.1) |

| II | 597 (46.8) |

| III | 436 (34.1) |

| Obstruction | 230 (18) |

| Perforation | 111 (8.7) |

| Synchronous tumors | 68 (5.3) |

SD: standard deviation; ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CEA: Carcinoembryonic Antigen.

Surgical and pathological characteristics.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Urgent surgery | 295 (23.1) |

| Surgical approach | |

| Open | 1145 (89.7) |

| Laparoscopy | 104 (8.1) |

| Laparoscopy converted to open | 28 (2.2) |

| Non-colorectal surgeon | 227 (17.8) |

| Extended resection | 167 (13.1) |

| Anastomosis | 1141 (89.4) |

| Diverting stoma | 22 (1.7) |

| Mucinous component | 133 (10.4) |

| Tumor differentiation | |

| Well differentiated | 198 (15.5) |

| Moderately differentiated | 865 (67.7) |

| Poorly differentiated | 65 (5.1) |

| Not available | 149 (11.7) |

| Lymph nodes isolated | |

| <12 | 528 (41.3) |

| ≥12 | 694 (54.3) |

| Not available | 55 (4.3) |

| Infiltration on specimen | |

| Vascular | 244 (19.1) |

| Lymphatic | 228 (17.9) |

| Peri-neural | 214 (16.8) |

| pT | |

| 1 | 104 (8.1) |

| 2 | 163 (12.8) |

| 3 | 801 (62.7) |

| 4 | 209 (16.4) |

| pN | |

| 0 | 842 (65.9) |

| 1 | 308 (24.1) |

| 2 | 127 (9.9) |

| Stage | |

| I | 244 (19.1) |

| II | 597 (46.8) |

| III | 436 (39.1) |

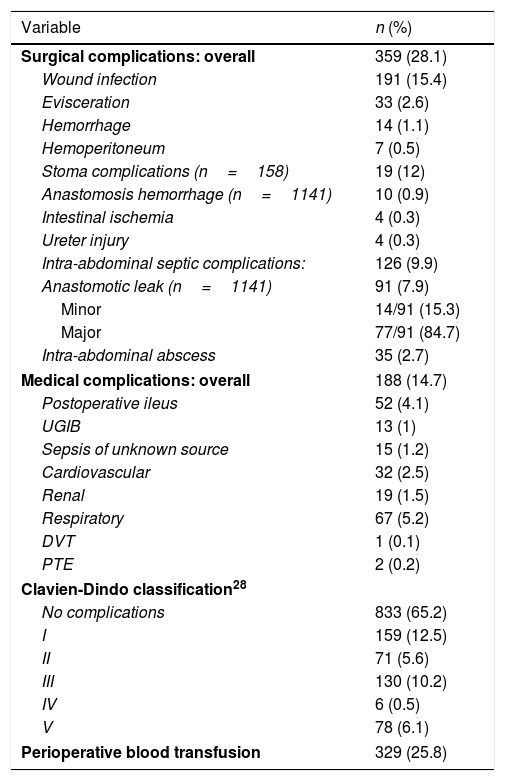

Overall 30-day morbidity was 34.5%, with a re-intervention rate of 9.4%. A BT was administered to 25.8% of the patients. IASC occurred in 9.9% of patients. Surgical site infections were the most common complication (15.4%). Overall 30-day mortality was 6.1%, occurring in 4.4% and 11.9% of patients who underwent elective or urgent surgery, respectively. Table 3 summarizes perioperative mortality and morbidity.

Postoperative morbidity and mortality.

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Surgical complications: overall | 359 (28.1) |

| Wound infection | 191 (15.4) |

| Evisceration | 33 (2.6) |

| Hemorrhage | 14 (1.1) |

| Hemoperitoneum | 7 (0.5) |

| Stoma complications (n=158) | 19 (12) |

| Anastomosis hemorrhage (n=1141) | 10 (0.9) |

| Intestinal ischemia | 4 (0.3) |

| Ureter injury | 4 (0.3) |

| Intra-abdominal septic complications: | 126 (9.9) |

| Anastomotic leak (n=1141) | 91 (7.9) |

| Minor | 14/91 (15.3) |

| Major | 77/91 (84.7) |

| Intra-abdominal abscess | 35 (2.7) |

| Medical complications: overall | 188 (14.7) |

| Postoperative ileus | 52 (4.1) |

| UGIB | 13 (1) |

| Sepsis of unknown source | 15 (1.2) |

| Cardiovascular | 32 (2.5) |

| Renal | 19 (1.5) |

| Respiratory | 67 (5.2) |

| DVT | 1 (0.1) |

| PTE | 2 (0.2) |

| Clavien-Dindo classification28 | |

| No complications | 833 (65.2) |

| I | 159 (12.5) |

| II | 71 (5.6) |

| III | 130 (10.2) |

| IV | 6 (0.5) |

| V | 78 (6.1) |

| Perioperative blood transfusion | 329 (25.8) |

UGIB: Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding; DVT: Deep vein thrombosis; PTE: pulmonary thromboembolism.

Median follow-up was 66 (range 41–101) months. During follow-up, 247 (19.3%) patients developed a recurrence, which was classified as LR in 81 (6.3%). The actuarial 5-year rates of LR, DFS, and CSS were 7%, 79.8%, and 85.1%.

At Cox regression analysis, the timeframe of surgery, pT status (HR 9.35, 95%CI 1.23–70.99 for T4), and pN status (HR 2.57, 95%CI 1.39–4.72 for N2) were independent risk factors for LR. DFS was worse with bowel obstruction (HR 1.95, 95%CI 1.39–2.71), advanced pT (HR 7.65, 95%CI 2.36–24.80 for T4) and pN status (HR 4.01, 95%CI 2.84–5.66 for N2) and it was improved if the operating surgeon had expertise in colorectal surgery (HR 0.64, 95%CI 0.45–0.92). The timeframe of surgery was also associated with DFS (Table 4). The same five variables significantly predicted shorter CSS, as well as the type of procedure performed (Table 4). IASC and BT were not associated with LR, DFS, and CSS, neither alone nor combined (Tables 4 and 5).

Multivariate analysis of variables associated with local recurrence and disease free survival: significant factors plus IASC, BT, and IASC+BT. HR>1 HR>1 is associated with increased risk of local or distant recurrence.

| Local recurrence | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | p value |

| Obstruction | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.18 |

| Yes | 1.52 | 0.89–2.58 | |

| pT | |||

| 1 | 1 | – | 0.001 |

| 2 | 0.59 | 0.03–9.50 | |

| 3 | 4.44 | 0.59–32.89 | |

| 4 | 9.35 | 1.23–70.99 | |

| pN | |||

| 0 | 1 | – | 0.006 |

| 1 | 1.75 | 1.06–2.89 | |

| 2 | 2.57 | 1.39–4.72 | |

| Timeframe of surgery | |||

| 1993–1998 | 1 | – | 0.04 |

| 1999–2004 | 0.45 | 0.45–0.24 | |

| 2005–2010 | 0.74 | 0.44–1.24 | |

| Procedure performed | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 1 | – | 0.53 |

| Left hemicolectomy | 0.74 | 0.31–1.78 | |

| Anterior resection | 0.74 | 0.42–1.29 | |

| Subtotal colectomy | 0.78 | 0.26–2.32 | |

| Hartmann's | 1.38 | 0.70–2.69 | |

| Segmental colectomy | 1.73 | 0.41–7.38 | |

| Total colectomy | 0.35 | 0.05–2.60 | |

| IASC | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.21 |

| Yes | 1.73 | 0.73–4.09 | |

| BT | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.37 |

| Yes | 1.28 | 0.74–2.22 | |

| Interaction IASC+BT | 1.32 | 0.38–4.51 | 0.66 |

| Disease-free survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | p value |

| Obstruction | |||

| No | 1 | – | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1.95 | 1.39–2.71 | |

| Operating surgeon | |||

| General | 1 | 0.02 | |

| Colorectal | 0.64 | 0.45–0.92 | |

| pT | |||

| 1 | 1 | – | <0.001 |

| 2 | 1.87 | 0.51–6.82 | |

| 3 | 4.57 | 1.44–14.52 | |

| 4 | 7.65 | 2.36–24.80 | |

| pN | |||

| 0 | 1 | – | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2.41 | 1.80–3.22 | |

| 2 | 4.01 | 2.84–5.66 | |

| Disease-free survival | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | p value |

| Timeframe of surgery | |||

| 1993–1998 | 1 | – | 0.02 |

| 1999–2004 | 0.62 | 0.45–0.87 | |

| 2005–2010 | 0.75 | 0.55–1.02 | |

| Procedure performed | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 1 | – | 0.05 |

| Left hemicolectomy | 1.02 | 0.63–1.64 | |

| Anterior resection | 0.90 | 0.65–1.24 | |

| Subtotal Colectomy | 1.49 | 0.88–2.52 | |

| Hartmann's | 1.57 | 1.03–2.39 | |

| Segmental colectomy | 2.28 | 1.04–5.00 | |

| Total colectomy | 0.89 | 0.41–1.94 | |

| IASC | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.42 |

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.38–1.49 | |

| BT | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.10 |

| Yes | 1.29 | 0.96–1.75 | |

| Interaction IASC+BT | 1.93 | 0.79–4.72 | 0.15 |

IASC: Intra-abdominal septic complications; BT: blood transfusions; HR: Hazard Ratio; CI: confidence intervals. Significant values in bold.

Multivariate analysis of variables associated with cancer-specific survival. HR>1 associated with cancer-related mortality.

| Variable | HR | 95%CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 1 | – | 0.59 |

| Female | 0.92 | 0.69–1.24 | |

| Age | 1.00/year | 0.99–1.02 | 0.57 |

| ASA grade | |||

| I–II | 1 | – | 0.28 |

| III–IV | 1.32 | 0.92–1.91 | |

| CEA | |||

| ≤5ng/ml | 1 | – | 0.61 |

| >5ng/ml | 1.33 | 0.93–1.91 | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Right | 1 | – | 0.54 |

| Transverse | 0.95 | 0.40–2.26 | |

| Left | 0.67 | 0.33–1.37 | |

| Obstruction | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.001 |

| Yes | 1.89 | 1.28–2.79 | |

| Perforation | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.23 |

| Yes | 1.55 | 0.81–2.31 | |

| Surgeon | |||

| General | 1 | – | 0.04 |

| Colorectal | 0.554 | 0.37–0.83 | |

| Extended resection | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.18 |

| Yes | 0.72 | 0.45–1.16 | |

| Mucinous component | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.61 |

| Yes | 0.88 | 0.54–1.44 | |

| Tumor differentiation | |||

| Well | 1 | – | 0.66 |

| Moderate | 0.74 | 0.47–1.18 | |

| Poor | 0.76 | 0.37–1.58 | |

| pT | |||

| 1 | 1 | – | 0.001 |

| 2 | 2.03 | 0.42–9.72 | |

| 3 | 4.36 | 1.04–18.28 | |

| 4 | 7.73 | 1.77–33.72 | |

| pN | |||

| 0 | 1 | – | <0.001 |

| 1 | 2.88 | 2.04–4.06 | |

| 2 | 4.39 | 2.84–6.78 | |

| Lymphatic invasion | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.81 |

| Yes | 0.96 | 0.66–1.38 | |

| Vascular invasion | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.05 |

| Yes | 1.57 | 0.99–2.48 | |

| Neural invasion | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.68 |

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.58–1.44 | |

| Timeframe of surgery | |||

| 1993–1998 | 1 | – | 0.002 |

| 1999–2004 | 0.54 | 0.37–0.80 | |

| 2005–2010 | 0.49 | 0.32–0.76 | |

| Procedure performed | |||

| Right hemicolectomy | 1 | – | 0.005 |

| Left hemicolectomy | 0.69 | 0.25–1.9 | |

| Anterior resection | 0.74 | 0.29–1.86 | |

| Subtotal Colectomy | 1.76 | 0.77–4.03 | |

| Hartmann's | 1.54 | 0.59–3.98 | |

| Segmental colectomy | 2.26 | 0.72–7.11 | |

| Total colectomy | 0.58 | 0.19–1.82 | |

| IASC | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.53 |

| Yes | 0.78 | 0.36–1.69 | |

| BT | |||

| No | 1 | – | 0.06 |

| Yes | 1.39 | 0.98–1.97 | |

| Interaction IASC+BT | 1.12 | 0.35–3.56 | 0.84 |

ASA: American Society of Anesthesiologists; CEA: Carcinoembryonic Antigen; IASC: Intra-abdominal septic complications; BT: blood transfusions; HR: Hazard Ratio; CI: confidence intervals. Significant values in bold.

In our study we explored the impact of IASC and BT, either alone or combined, on long-term oncologic outcomes of patients who underwent curative surgery for colon cancer. Perioperative IASC and BT did not increase 5-year LR rates, and they did not result in worse DFS and CSS. Obstruction, pT and pN status, as well as the expertise of the operating surgeon, the type of procedure performed and the timeframe of surgery, independently predicted detrimental outcomes of surgery, irrespective of septic complications and BT.

Different authors suggested that postoperative complications might worsen oncological outcomes.3,4,11,26,29 However, there are significant discrepancies in published studies,4 presumably due to the lack of standardized classification and collection of complications. Including patients undergoing surgery for colon as well as for rectal tumors may further complicate the interpretation of findings.9–11

AL rank among the most severe postoperative complications in colorectal surgery, with a reported incidence that varies between 3% and 12%.5,13,30 In our series, AL rate was 7.9%, accounting for 72.2% of all IASC complications. AL have negative effects on long-term oncological results, including both LR and systemic recurrences, and reduces overall survival.3,5,9–12,30,31 Others did not confirm the association between AL and survival9 although most studies agree on increased risk of recurrence.

Several etiological pathways and theories underlying the adverse effects of AL on recurrences and survival rates have been proposed. The reasons underlying these associations are not fully understood, and might be only partially related to delayed postoperative treatments.13 AL could contribute to the implantation of tumor cells deposited extra-luminally in the pelvis.32,33 The acute inflammatory response that follows IASC and septic shock34 interferes with apoptosis, and might facilitate mitosis of implanted cancer cells and progression to metastases.35,36 However, these hypotheses have not been unequivocally proven, and other factors involved in tumor growth have been investigated. Among them, angiogenesis represents an essential component in tumor recurrence.37 The vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is an angiogenetic agent38 that has been associated with shorter DFS39 and overall survival40 in patients with advanced colorectal cancer. Pera et al. found that the increase of the postoperative inflammatory response was associated with an increase in angiogenesis and tumor growth after excision of colon cancer in mice.41 In further experimental studies, the same authors concluded that postoperative IASC increased angiogenesis and tumor recurrence after colon cancer surgery.42,43 A subsequent clinical research investigating the bimolecular response associated with postoperative IASC, suggested that septic complications increased IL-6 and VEGF compared with patients who did not develop any complications.44 The authors inferred that these pathways may be responsible for higher recurrence rates after AL.44 In our study, we found that IASC did not impair LR, DFS and CSS, suggesting that this aspect needs to be further elucidated to demonstrate whether the exaggerated inflammatory response may lead to a clinically relevant angiogenetic effect, which may be able to promote recurrences, eventually impairing survival.

Perioperative BT are commonly used for patients suffering from colon cancer, who are candidates to curative resection or after surgery. BT themselves have been associated with tumor recurrence and mortality after colorectal cancer,15 but other authors did not observe worse prognosis in patients who received BT.23,24 More recent meta-analyses seemed to confirm the trend16,21 but the significant contribute of confounding factors (e.g. “R1”/“R2” resections or exfoliation of cancer cells during surgery22) could not be removed. We did not observe any effects on LR, DFS, and CSS in Cox regression analysis.

Mynster et al. investigated the combined effect of BT and IASC with regards to oncological results of 740 patients who underwent curative surgery for colorectal cancer.23 They concluded that the association of BT and IASC increased recurrences and shortened overall survival.23 We were able to confute this finding by assessing the combined effect of BT and IASC in our analyses, which showed no significant impact on LR, DFS, and CSS.

Study limitationsThe retrospective design is the main limitation of our study. Patients were operated on during a window of time wide enough to potentially include significant modifications in the overall management. On the other hand, the sample size of our series allowed us to achieve reliable results. Prognostic factors can be adequately addressed with retrospective series, provided that events and data are collected prospectively and with a standardized method.

Another limitation that is worth mentioning, is the relatively high number of patients with less than 12 nodes examined (41.3%, Table 2). It should be noted that the present study covers a wide timeframe, involving different methods for specimen processing and lymph node assessment. Studies from our center have previously reported that several changes and improvements in specimen assessment have resulted in an increased number of nodes being retrieved over time (patients with>12 nodes increased from 8.1% in 1993–1998 to 67.3% in 2005–2010; p<0.001).45–47 This could probably be attributed to a more effective collaboration with the pathologists, and to the formal appointment of pathologists with expertise in colorectal specimens processing to our MDT in 2005.

Including a wide timeframe could have also affected the results. However BT, IASC, and their combination were not associated with impaired LR, DFS and CSS even when the year of surgery was forced into the models of Cox regression.

Most studies that investigated the role of BT and IASC on the long-term survival of colon cancer patients in clinical settings share similar limitations. Studies often report on series with smaller sample size, they might only include elective procedures, or pool data of patients with colon and rectal cancers.3,5,9–12,14,23,24,30,31 Small number of observed events and inaccurate data collection resulted in the unsuitability of running multivariate regression analyses.16,21,22 Furthermore, few studies explored the combined effect of BT and IASC, and the statistical method may not have been adequate. As an example, they assessed four different groups (i.e. IASC, BT, IASC+BT, no complications), rather than using an interaction model.23

We would suggest that our results are more solid, because the Cox regression models excluded the confounding effect of other variables. Moreover, we were able to identify additional factors that might be more relevant in terms of LR, DFS and CSS after colon cancer surgery. Specifically, cancers presenting with obstruction, pT and pN status, and the expertise of the operating surgeon were of paramount relevance, along with the type of procedure performed (Tables 4 and 5).

This study analyzed a large series of patients with colon cancer who underwent surgery with curative intent at a specialized colorectal surgery unit of a tertiary hospital. IASC and BT, and their combination, did not affect the oncological outcomes in terms of LR, DFS and CSS. Other variables impaired survival, including intestinal obstruction, and T and N status.

The clinical implications of IASC and especially AL are important, and they can have a significant effect on quality of life or require further treatments. Irrespective of their impact on disease recurrence, further research is needed to elucidate their relationship with BT, and to facilitate their prevention and management.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors report no conflict of interest.