Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) is associated with important mortality. More information is needed in order to improve NVUGIB management. The aims of this study were: (a) characterizing Portuguese patients and clinical approaches used in NVUGIB, (b) comparing management used in Portugal with management globally used in European countries, (c) identify factors associated with management options, and (d) identify factors associated with adverse outcome.

MethodsENERGiB was an observational, retrospective cohort study, on NVUGIB with endoscopic evaluation, carried across Europe. This study focuses on Portuguese patients of the ENERGiB study. Patients were managed according to routine care. Later, data were collected from files. Multivariate/univariate analyses were conducted on predictive factors of poor outcome and clinical decisions.

ResultsPatients (n=404) were mostly men (66.8%), mean age 68, with co-morbidities (72%), frequently on NSAIDs/aspirin. Most were assisted by general medical (57.8%) or surgical team (20.6%), only 19.4% by gastroenterology/GI-bleeding team. PPI was largely used. Gastric/duodenal ulcers, erosive gastritis and esophagitis were the main bleeding causes. 10% had bleeding persistence/recurrence. Death occurred in 24 patients, 20 from a non-bleeding related cause. Poor outcomes were related with age >65, co-morbidities, fresh blood haematemesis, shock/syncope, bleeding through previous nasogastric tube, massive fluid replacement or transfusions besides erythrocytes.

ConclusionsThis study contributed to characterization of Portuguese patients and NVUGIB episodes in real clinical setting and identified factors associated with a poor outcome. It also identified differences, especially in the organization of GI bleeding teams, which might help us to improve the management of these patients.

La hemorragia digestiva alta no varicosa (HDANV) se asocia con un grado importante de mortalidad. Para mejorar el manejo de la HDANV es necesario recopilar más información. Los objetivos de este estudio fueron: a) caracterizar los pacientes portugueses y los enfoques clínicos utilizados para la HDANV, b) comparar el enfoque utilizado en Portugal con los enfoques generales utilizados en los otros países europeos, c) identificar los factores asociados con las opciones de tratamiento, d) identificar los factores asociados con los desenlaces adversos.

MétodosENERGiB es un estudio de cohorte, observacional y retrospectivo sobre la HDANV en el que se utilizó evaluación endoscópica y realizado en toda Europa. Este estudio se centra en los pacientes portugueses del estudio ENERGiB. Los pacientes fueron tratados mediante la pautas de atención habituales. Más tarde, se obtuvieron datos a partir de los historiales. Se realizaron análisis de multivarianza y univarianza con los factores predictivos de evolución y decisiones clínicas deficientes.

ResultadosLos pacientes (n=404) eran en su mayoría hombres (66,8%), con una edad media de 68 años, presencia de comorbilidades (72%), y, con frecuencia, uso de AINEs o aspirina. La mayoría fueron atendidos por médicos de familia (57,8%) o equipos quirúrgicos (20,6%), sólo el 19,4% fue tratado por equipos de gastroenterología /sangrado del IG. Los inhibidores de la bomba de protones (IBP) se utilizaron con frecuencia. Las úlceras gástricas o duodenales, la gastritis erosiva y la esofagitis fueron las causas principales del sangrado. El 10% presentaba persistencia o recidiva del sangrado. La muerte ocurrió en 24 pacientes, 20 por causas no relacionadas con el sangrado. Los malos resultados estuvieron relacionados con una edad > 65 años, comorbilidad, hematemesis de sangre fresca, shocks o síncope, sangrado por sonda nasogástrica previa, reemplazo masivo de líquidos o transfusiones aparte de eritrocitos.

ConclusionesEste estudio ha contribuido a la caracterización de los pacientes portugueses y de los episodios de HDANV en un entorno clínico real e identifica factores relacionados con un mal desenlace. También se identificaron diferencias, especialmente en la organización de los equipos de hemorragia gastrointestinal, que podrían ayudar a mejorar el manejo de estos pacientes.

The nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding (NVUGIB) is a frequent cause of hospitalization.1–5 In recent years there have been major advances in pharmacological and endoscopic treatment, reducing the morbidity associated with NVUGIB. Prospective studies have shown that the clinical evolution of these patients can improve when more suitable approaches are used. It has been possible to reduce the recurrence of bleeding,6–9 the need for transfusion support7,9 and surgery,7 aspects that clearly have benefited from the improvement of the clinical approach. The length of hospitalization was also reduced,7,9 allowing better use of available resources.

Despite the therapeutic advances the mortality associated with the NVUGIB remains significant.7,9–12 The reasons for the high mortality numbers are unclear, but it has been suggested that it may be due to the change in the patients’ characteristics, who are now older and with more frequent co-morbidities associated.

Despite the existence of multiple protocols and recommendations for management of patients with NVUGIB, there is the widespread belief that the clinical approach varies between countries and also between hospitals with different dimensions. Such variations may be not only due to pharmacological and endoscopic treatment options,6 but also to other aspects including the availability of early endoscopy,13 the systematic use of protocols or the organization and establishment of the medical teams that assist these patients.14

Among clinicians, there has been a renewed interest in the problem of gastrointestinal bleeding. Recently, the Portuguese Society of Digestive Endoscopy has published a set of recommendations for the treatment of patients with NVUGIB.15 A multicentric study has evaluated the NVUGIB related to the acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) consumption in nine Portuguese hospitals,16 contributing to relaunch the debate on NVUGIB in this context.17

In order to evaluate the clinical approaches used in the real context in several European countries, the ENERGiB study was developed (European Survey of Non-variceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding, NCT00797641). This was an observational, retrospective, international, multicentric study involving 7 European countries, 123 centres and 2660 patients. Its primary objective was to report the clinical outcomes associated with endoscopic and clinical pharmacological approaches used in the NVUGIB, namely: (i) bleeding persistence, (ii) recurrent bleeding, (iii) surgery and (iv) mortality. Beyond this objective, the following secondary objectives were defined: (i) to describe the clinical approaches and compare them between countries and types of hospitals, (ii) to establish predictive factors related to clinical approaches, (iii) to establish predictive factors related to the clinical outcomes and (iv) to assess the resource consumption in patients with NVUGIB. The results of this European study have been presented and published and have contributed to confirm the existence of an important variability in the clinical management of NVUGIB between countries and centres of different characteristics, to better understand the treatment options and to identify predictive factors of poor prognosis.18

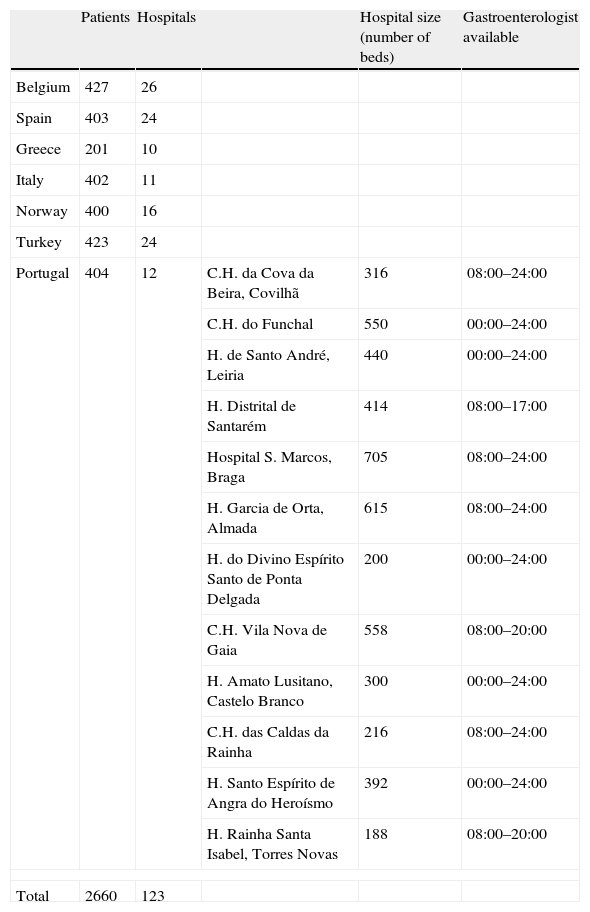

In Portugal, the ENERGiB study involved 404 patients and 12 hospitals in the mainland, Madeira and Azores (Table 1). Centres involved were of different size and serving populations with different characteristics, including hospitals from the major metropolitan areas of Lisbon and Oporto and others who serve predominantly rural populations. There was a wide range of hospital sizes, evaluated using the number of beds from 216 to 705. Nevertheless, most had a gastroenterologist and endoscopy available 24h, around the clock, or from 8:00 to midnight.

Hospitals enrolled in the ENERGiB study.

| Patients | Hospitals | Hospital size (number of beds) | Gastroenterologist available | ||

| Belgium | 427 | 26 | |||

| Spain | 403 | 24 | |||

| Greece | 201 | 10 | |||

| Italy | 402 | 11 | |||

| Norway | 400 | 16 | |||

| Turkey | 423 | 24 | |||

| Portugal | 404 | 12 | C.H. da Cova da Beira, Covilhã | 316 | 08:00–24:00 |

| C.H. do Funchal | 550 | 00:00–24:00 | |||

| H. de Santo André, Leiria | 440 | 00:00–24:00 | |||

| H. Distrital de Santarém | 414 | 08:00–17:00 | |||

| Hospital S. Marcos, Braga | 705 | 08:00–24:00 | |||

| H. Garcia de Orta, Almada | 615 | 08:00–24:00 | |||

| H. do Divino Espírito Santo de Ponta Delgada | 200 | 00:00–24:00 | |||

| C.H. Vila Nova de Gaia | 558 | 08:00–20:00 | |||

| H. Amato Lusitano, Castelo Branco | 300 | 00:00–24:00 | |||

| C.H. das Caldas da Rainha | 216 | 08:00–24:00 | |||

| H. Santo Espírito de Angra do Heroísmo | 392 | 00:00–24:00 | |||

| H. Rainha Santa Isabel, Torres Novas | 188 | 08:00–20:00 | |||

| Total | 2660 | 123 | |||

Given the importance of ENERGIB study in the national context, the authors chose to analyse the results for Portugal aiming:

- 1.

To contribute to characterize Portuguese patients suffering from NVUGIB and the clinical approaches used in these patients.

- 2.

To compare the clinical approaches used in Portuguese patients to clinical approaches used in every European country involved in the study.

- 3.

To identify the factors associated with the options used for the management of these patients.

- 4.

Identify factors associated with adverse clinical outcomes, including persistent bleeding after endoscopy, recurrent bleeding, need for surgery and mortality.

ENERGiB was an observational, retrospective cohort study carried out across multiple centres in seven countries (Belgium, Greece, Italy, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Turkey). Eligible patients were adult (aged 18 years or older) men and women who underwent endoscopy due to NVUGIB between October 1 and November 30, 2008. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were admitted to the hospital because of NVUGIB and if they were admitted for another reason but developed NVUGIB during hospitalization. NVUGIB was defined as haematemesis/coffee ground vomiting, melaena, haematochezia and other clinical or laboratory evidence of acute blood loss from the upper GI tract confirmed by upper GI endoscopy. Data were collected retrospectively from patients’ medical records between the beginning of the NVUGIB episode and up to 30 days afterwards. Patients with incomplete collected data were excluded from the study. As this was a non-interventional study, the management of patients was according to clinical practice of each centre.

Clinical resultsClinical results such as persistent bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy, recurrent bleeding, need for surgery to control bleeding and mortality were considered negative results.

Persistent bleeding was defined as the presence of haemorrhage during the endoscopy which did not respond to the endoscopic therapeutic or one of the following criteria detected after endoscopy: detecting red fresh blood in the nasogastric aspirate; shock with heart rate >100beats/min and/or systolic blood pressure <100mmHg, or need for substantial blood transfusion (transfusion of 3 or more units of blood within 4h).

Recurrent bleeding was defined as recurrent haemorrhage of fresh blood or shock associated melaena, or a decrease in haemoglobin level of ≥20g/L following initial successful treatment.

Statistical analysisPatients’ clinical information was summarized using descriptive statistical measures, defining the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and relative frequencies as percentages (%) for categorical variables. In the results presentation the percentages have been rounded to the unit. We tried to identify clinical determinants associated with negative clinical outcomes and options used in the clinical management of patients.

A multivariable analysis was performed using a mixed-model logistic regression. The definition of the model and the variables selection were based on a priori clinical and biological information about the studied condition. The use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) before endoscopy was considered an adjustment factor in every model. Raw (univariable) and multivariable adjusted odds ratios and respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated from the logistic regression coefficients and standard errors. The significance level was 5% for keeping independent predictors in the models.

All results with p-value less than the significance level, defined as 0.05 (5%) were considered statistically significant. Data were analysed using the SAS program.

Study limitationsThis was a retrospective study limited to two months of a single year. Being a retrospective study, bias cannot be excluded in the analyses of the poor outcome associated factors. The database does not allow comparing Portuguese data with non-Portuguese data. When considered of interest, national data were compared with the whole of the 2660 pan-European patients, allowing to infer useful information, but not to make a comparative statistical analysis.

ResultsPortuguese patients’ characterizationA total of 404 Portuguese patients with NVUGIB were included in the study, with a mean age of 68.5±17.1 years. Two-thirds of the included patients (66.8%) were men. Tobacco smoking was identified in 9% and regular alcohol consumption in 17% of the studied patients. Sixteen percent had previous history of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Most patients (72%) had one or more co-morbid condition, including heart, respiratory, renal, hepatic or neoplasic disease.

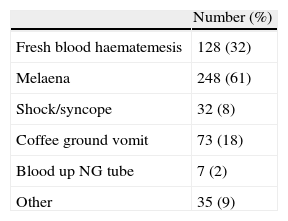

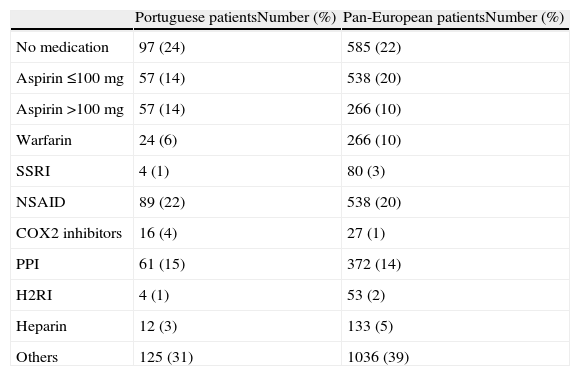

Only in 18% of cases, the NVUGIB occurred in patients previously hospitalized. The remaining 82% were admitted due to a bleeding episode. The majority of patients (56%) remained haemodynamically stable. The most commonly reported symptom of NVUGIB was melaena (61%), but haematemesis of fresh blood (32%) or coffee grounds bleeding (18%) were also very common (Table 2). Only 24% of patients were not taking any medication. The intake of anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and aspirin (ASA) in low or high doses was very common (Table 3). More than 15% of patients were taking PPIs during the bleeding episode.

Current medication at admission.

| Portuguese patientsNumber (%) | Pan-European patientsNumber (%) | |

| No medication | 97 (24) | 585 (22) |

| Aspirin ≤100mg | 57 (14) | 538 (20) |

| Aspirin >100mg | 57 (14) | 266 (10) |

| Warfarin | 24 (6) | 266 (10) |

| SSRI | 4 (1) | 80 (3) |

| NSAID | 89 (22) | 538 (20) |

| COX2 inhibitors | 16 (4) | 27 (1) |

| PPI | 61 (15) | 372 (14) |

| H2RI | 4 (1) | 53 (2) |

| Heparin | 12 (3) | 133 (5) |

| Others | 125 (31) | 1036 (39) |

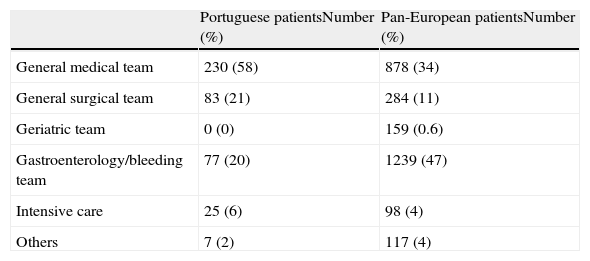

The majority of patients was assisted by general medical wards (57.8%) or by a surgical team (20.6%). Only 19.4% were assisted directly by the gastroenterology or by a specific team for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding (Table 4).

Team responsible for intra-hospital management.

| Portuguese patientsNumber (%) | Pan-European patientsNumber (%) | |

| General medical team | 230 (58) | 878 (34) |

| General surgical team | 83 (21) | 284 (11) |

| Geriatric team | 0 (0) | 159 (0.6) |

| Gastroenterology/bleeding team | 77 (20) | 1239 (47) |

| Intensive care | 25 (6) | 98 (4) |

| Others | 7 (2) | 117 (4) |

The clinical risk score evaluated by the expected clinical risk scales (Rockall, Blatchford or ASA scales) was not registered in any of the Portuguese patients’ clinical records. Even before the diagnostic endoscopy, anti-secretory therapy was administered to most patients (68%). Only 1% of evaluated patients were treated with H2 receptor blockers. The other 67% used a PPI. The most frequently used PPIs were esomeprazole (33%), omeprazole (22%) and pantoprazole (12%). In most patients (53%), the PPI was administered as an intra-venous bolus (IV), a PPI infusion was administered in 10% of the included patients and in 4% PPI was administered orally.

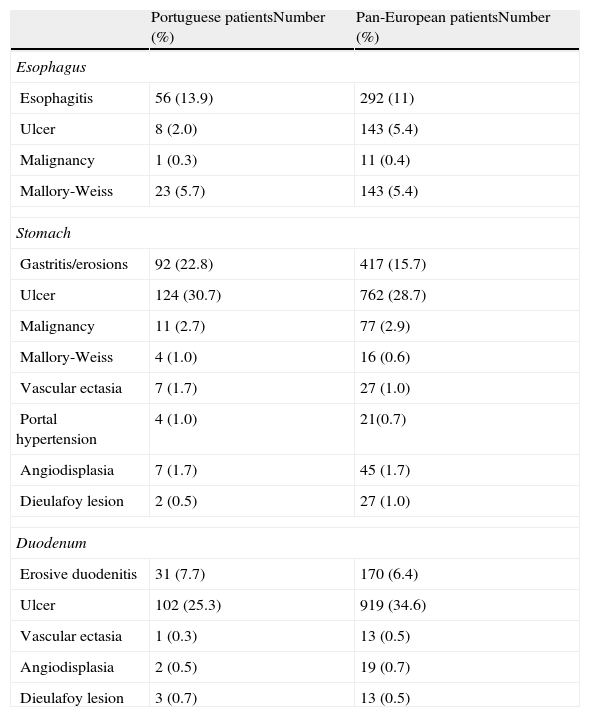

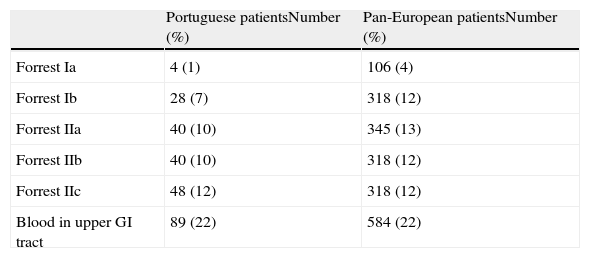

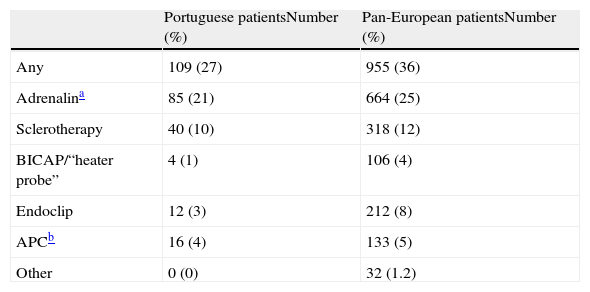

All patients underwent an endoscopy. The most frequent diagnosis was gastric ulcer. In the oesophagus, the most frequent diagnosis was oesophagitis and in duodenum was ulcer (Table 5). Signs of recent haemorrhage were present in most tests (Table 6). Only 27% of patients have undergone endoscopic therapy and about one-third has been treated with injection of adrenaline with no other associated procedure (Table 7). After endoscopy, 94% of patients were treated with a PPI, esomeprazole in 51% of them. The PPI was administered as a bolus in 57%, by a PPI infusion in 17% and orally in 28%.

Endoscopic diagnosis.

| Portuguese patientsNumber (%) | Pan-European patientsNumber (%) | |

| Esophagus | ||

| Esophagitis | 56 (13.9) | 292 (11) |

| Ulcer | 8 (2.0) | 143 (5.4) |

| Malignancy | 1 (0.3) | 11 (0.4) |

| Mallory-Weiss | 23 (5.7) | 143 (5.4) |

| Stomach | ||

| Gastritis/erosions | 92 (22.8) | 417 (15.7) |

| Ulcer | 124 (30.7) | 762 (28.7) |

| Malignancy | 11 (2.7) | 77 (2.9) |

| Mallory-Weiss | 4 (1.0) | 16 (0.6) |

| Vascular ectasia | 7 (1.7) | 27 (1.0) |

| Portal hypertension | 4 (1.0) | 21(0.7) |

| Angiodisplasia | 7 (1.7) | 45 (1.7) |

| Dieulafoy lesion | 2 (0.5) | 27 (1.0) |

| Duodenum | ||

| Erosive duodenitis | 31 (7.7) | 170 (6.4) |

| Ulcer | 102 (25.3) | 919 (34.6) |

| Vascular ectasia | 1 (0.3) | 13 (0.5) |

| Angiodisplasia | 2 (0.5) | 19 (0.7) |

| Dieulafoy lesion | 3 (0.7) | 13 (0.5) |

Patients may have more than one diagnosis.

In 6% of patients the initial bleeding persisted after the endoscopy. During hospitalization 5% of patients had a bleeding recurrence and 2% had relapsed after discharge, during the 30-day study. Globally, in about 10% of the studied patients persistence and/or recurrence of the NVUGIB was registered.

It was necessary to transfuse 92% of patients. Additional endoscopies were needed in 27% of patients, especially for control or for repeating the therapeutic procedures (18%), due to persistent or recurrent bleeding (4%) or due to inadequate observation conditions in the first test (3%). Globally, a mean of 1.3 endoscopies per patient during hospitalization was recorded and 1.4 endoscopies per patient within 30 days. No Portuguese patient was submitted to angiographic coiling. Twelve patients underwent surgery, eight of which, during the time hospitalization and four were readmitted for surgery after discharge.

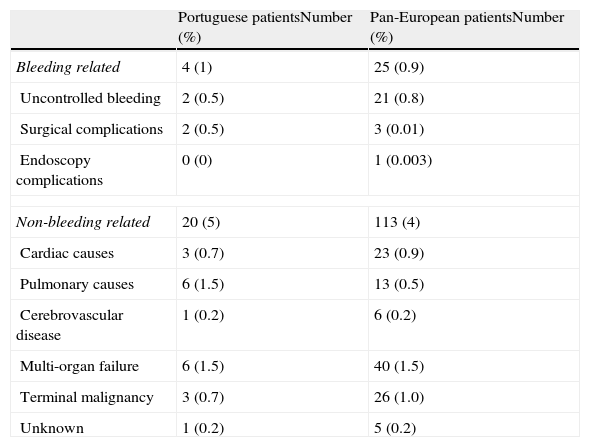

A total of 24 patients (4.8%) died. Only in 4 of these cases, death was directly related to a bleeding episode: 2 cases by initial uncontrolled NVUGIB and another two by surgery complications. In the remaining 20 cases, death was associated with systemic complications that there had not been linked as a direct result of the NVUGIB (Table 8).

Cause of death.

| Portuguese patientsNumber (%) | Pan-European patientsNumber (%) | |

| Bleeding related | 4 (1) | 25 (0.9) |

| Uncontrolled bleeding | 2 (0.5) | 21 (0.8) |

| Surgical complications | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.01) |

| Endoscopy complications | 0 (0) | 1 (0.003) |

| Non-bleeding related | 20 (5) | 113 (4) |

| Cardiac causes | 3 (0.7) | 23 (0.9) |

| Pulmonary causes | 6 (1.5) | 13 (0.5) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) |

| Multi-organ failure | 6 (1.5) | 40 (1.5) |

| Terminal malignancy | 3 (0.7) | 26 (1.0) |

| Unknown | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.2) |

The association between some clinical features and the options used in the clinical management of patients was demonstrated. Thus, in our series of patients we have recorded the following aspects:

- 1.

Greater probability to be treated with a PPI before the endoscopy in patients:

- a.

With one or more co-morbidities (OR: 2.10, p=0.004).

- b.

Whose clinical condition is the fresh blood haematemesis (OR: 2.31, p=0.001).

- a.

- 2.

Regarding the probability of being submitted to endoscopic treatment:

- a.

Greater probability to undergo endoscopic treatment in patients whose clinical condition was fresh blood haematemesis (OR: 1.81, p=0.02).

- b.

Less probability to undergo endoscopic treatment in patients whose endoscopic diagnosis was oesophagitis (OR: 0.32, p=0.02).

- a.

- 3.

Greater probability to repeat a second endoscopy:

- a.

In hospitalized patients with NVUGIB episode compared with those in which the haemorrhage occurred during a hospitalization for other causes (OR: 2.50, p=0.02).

- b.

In patients whose endoscopic diagnosis was gastric ulcer (OR: 2.29, p=0.001).

- a.

The association between some clinical features and adverse clinical outcomes was also identified. Thus, we observed:

- 4.

Greater probability of persistent bleeding in the initial NVUGIB episode in patients with one or more co-morbidities (OR: 4.58, p=0.02). Although not reaching statistical significance (OR: 2.44, p=0.08) there is a statistical trend for women having higher risk of bleeding continuation than men.

- 5.

Patients are more likely to have a recurrent bleeding if:

- a.

They have one or more co-morbidities (OR: 3.37, p=0.04).

- b.

Their clinical condition is fresh blood haematemesis (OR: 2.41, p=0.02).

- a.

- 6.

Patients are more likely to undergo surgery if:

- a.

They are admitted to larger hospitals (>500 beds) (OR: 7.53, p=0.03).

- b.

Their clinical condition is fresh blood haematemesis (OR: 3.22, p=0.02).

- a.

- 7.

Overall, patients are more likely to develop complications, if:

- a.

They are admitted to larger hospitals (>500 beds) (OR: 2.76, p=0.03).

- b.

They are aged over 65 years (OR: 2.48, p=0.02).

- c.

They have one or more co-morbidities (OR: 5.56, p=0.005).

- d.

Their clinical condition is shock/syncope (OR: 5.52, p<0.001) or bleeding through the nasogastric tube previously placed for another reason (OR: 8.15, p=0.008).

- a.

Finally, in what concerns mortality the following has been registered:

- 8.

Greater probability of death in patients:

- a.

With one or more co-morbidities (OR: 10.57, p=0.007).

- b.

That in the first 12h of admission require massive fluid replacement (OR: 15.81, p<0.001) or transfusion of blood products besides red blood cells (OR: 24.01, p<0.001).

- a.

- 9.

Lower probability of death in patients:

- a.

Admitted due to the episode of upper gastrointestinal bleeding compared with those in which the haemorrhage occurred during a hospitalization for other causes (OR: 0.17, p<0.001).

- b.

Treated with NSAIDs, aspirin or warfarin (OR: 0.40, p=0.03).

- a.

The ENERGIB study was a retrospective observational study, which presents some limitations associated to its retrospective nature. However, it has the advantage of permitting to develop a clear picture of reality, allowing us to better understand our patients, recognize the strengths and weaknesses of our clinical activity identifying the aspects that need improvement.

This study contributes to characterize Portuguese patients with NVUGIB: predominantly male (around two-thirds), aged over 50 years, more than half was taking ASA and/or classical NSAIDs or COX2 inhibitors regularly. About 16% had previous history of bleeding and 16% were previously treated with anti-secretory agents, especially PPIs. Most patients were hospitalized for upper gastrointestinal bleeding, and only a minority had suffered bleeding during previous hospitalization.

Within the ENERGIB study, some differences can be found among the Portuguese experience and the overall experience with the 2660 pan-European patients, despite the described limitations. From the total of 2660 European patients, about half were assisted directly by the gastroenterology or by a team dedicated to gastrointestinal bleeding. This type of assistance based on specialty or on a dedicated team was available for less than 20% of the Portuguese patients, in contrast to the pan-European trend, where 47% of cases were assisted by the gastroenterology or by a specific team for bleeding patients. Part of this difference could be attributable to the integration of small hospitals with small gastroenterology services with few specialists. However, the proportion of large hospitals (>500 beds) or undersized (<500 beds) was similar in all countries. Organizational factors may be involved. Another difference, related to the initial clinical practice is the complete absence of patients’ clinical risk stratification, using the widely accepted scale of Rockall19 or any other. There is an ongoing debate and a wide range of opinions regarding the usefulness of using scales to access the clinical risk of NVUGIB patients. Nevertheless, Portugal was the only country where the use of these clinical risk scales was never recorded. These differences should incentivize, among us, a further discussion on the need for organizational structures and oriented teams to respond to gastrointestinal bleeding. It has already been demonstrated that adequate organization for the management of these patients may have a clinical impact14 either by gastroenterologists or in Internal Medicine Services. The recommendation for intensive treatment and special monitoring of patients with high levels of Rockall was already a topic of an editorial in the GE – the Portuguese Journal of Gastroenterology.20 On the contrary, the pharmacotherapeutical options were taken early and the administration of PPIs was adjusted in accordance with the endoscopic diagnosis. After endoscopy, the infusion of PPI rose from 10% to 17%, presumably in patients with ulcers and/or with risk of relapsing signs according to the endoscopic described aspects. The endoscopic diagnosis seems to be less severe than in the whole pan-European patients with less gastric and duodenal ulcers and more superficial erosive lesions. Also, the endoscopic signs of recurrence risk, assessed by the Forrest classification, seem to be less severe than in the whole pan-European patients. However, when analysing the diagnosis and endoscopic risk signs, endoscopic treatment actions were not performed with the desirable frequency. Many of these actions only included the injection of adrenaline that was never followed by any other therapeutic. This clinical option does not ensure the most effective haemostasis. Also, no Portuguese patient was submitted to angiographic coiling in contrast with a pan-European average of 1.17% of the patients.

Portuguese patients’ clinical evolution was similar to all of the 2660 pan-European patients and to the ones described in the literature. The clinical evolution has included about 10% of persistence and/or recurrence of the NVUGIB. This negative trend is significantly associated with the presence of co-morbidities and to the presentation as haematemesis of fresh blood. About a third of the included patients were submitted to a second endoscopy, especially aiming at repeating the treatment. It is also important to recognize that submitting patients to a second test was also associated with the initial diagnosis of a gastric ulcer and the need to exclude the diagnosis of gastric cancer. It was demonstrated that patients hospitalized prior to the occurrence of the bleeding episode tend to be less frequently submitted to this second evaluation. It can be admitted that this happened due to a better exam preparation for the exam in the inpatient setting than in an emergency situation. There were 12 patients (3%) submitted to surgery. The probability of being submitted to surgery increases with the presentation as fresh blood haematemesis, but also with the admission in larger hospitals (>500 beds), suggesting that these hospitals have more interventional surgical teams and/or that more severe patients are referred to the larger units. In general, the probability of developing complications is associated with the clinical presentation as shock or syncope, patients over 65 years of age, co-morbidities and admission at larger hospitals.

The majority of deaths among the 24 patients who died (20 patients/83% of deaths) were due to causes not directly related with NVUGIB. The risk of death is associated with the massive need for replacement of fluids within 12h reflecting the severity of the NVUGIB. But it is also associated with the existence of co-morbidities, the onset of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in patients previously hospitalized and the need for transfusions of blood products other than red blood cells, factors that reflect patients’ clinical severity.

A global look at the Portuguese results allow us to compare the factors leading to greater therapeutic intervention with those associated with unfavourable clinical course. Thus, what led to greater therapeutic intervention was: (a) presence of co-morbidities, (b) presentation as fresh blood haematemesis and (c) admission in larger hospitals. On the other hand, the factors associated with unfavourable outcome included: (a) presence of co-morbidities, (b) age >65 years, (c) transfusion of blood products other than red blood cells, (d) clinical presentation as shock/syncope, (e) replacement of massive fluids within 12h and (f) admission in larger hospitals. Apparently, the decision-making leading to greater therapeutic intervention took into account the most immediate aspect of the upper gastrointestinal bleeding evaluation and the fresh blood haematemesis, rather than the signals that reflect severe haemodynamic condition, presentation as shock/syncope or the need of massive fluid replacement. Moreover, aspects reflecting the overall clinical severity, age and the transfusion of blood products other than red blood cells (OR: 24 associated to mortality risk) did not seem to have been considered as the factors influencing treatment decisions. Although mortality was similar to the global pan-European 2660 patients, Portuguese patients have less ulcers and more superficial erosions and less high risk stigmata (Tables 5 and 6). Lower negative outcomes could be anticipated for these milder lesions. Portuguese negative outcomes were similar to the ones observed in the pan-European group. Organizational issues may be involved. All together, the low percentage of patients assisted directly by the gastroenterology or by a specific team for patients with gastrointestinal bleeding, the complete absence of patients’ clinical risk stratification and the absence of angiographic coiling, point to organizational limitations. It should reinforce the importance of reflecting on the need to create teams and hospital structures aimed to evaluate these patients early, stratify the risk and ensure the clinical follow-up of the most severe cases.

ConclusionsThe current analysis, evaluating the results of Portuguese patients included in the ENERGIB study, has achieved its main objectives. It has contributed to a better characterization of the Portuguese patients suffering from NVUGIB, and to the identification of the main factors associated with an unfavourable outcome, helping our Portuguese clinicians to identify which are the patients with major risk and worse prognosis. It has allowed us to observe in a real clinical setting, the clinical options used with patients with NVUGIB and to identify factors that are associated with more intensive therapeutic approaches. It has also allowed us to be aware of the need for a more frequent therapeutic intervention during urgent endoscopy. Although lacking statistical confirmation, the comparison of Portuguese and pan-European data is able to identify some differences, especially at an organizational level. The organizational differences combined with the divergence between the associated factors, the unfavourable outcomes and the factors that predispose to a greater therapeutic intervention, should raise the need to improve the organization of the teams and the hospital facilities especially dedicated to patients with gastrointestinal haemorrhages.

Conflict of interest statementThe authors declare no conflict of interest.