Infectious oesophagitis is the third most common cause of oesophagitis, after gastro-oesophageal reflux and eosinophilic oesophagitis.1 The most commonly implicated micro-organism is Candida, followed by herpes simplex virus (HSV) and cytomegalovirus.1 Concomitant infection with HSV and cytomegalovirus, though very uncommon, increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation.2,3

We report the case of a 65-year-old woman with a history of chronic alcoholism (more than 80 g of alcohol per day), type 2 diabetes mellitus, heart failure secondary to severe tricuspid insufficiency and persistent atrial fibrillation (being treated with apixaban). She was admitted to hospital for respiratory sepsis and decompensated heart failure and treated with piperacillin/tazobactam, intravenous corticosteroids and diuretics. Apixaban was replaced with low-molecular-weight heparin.

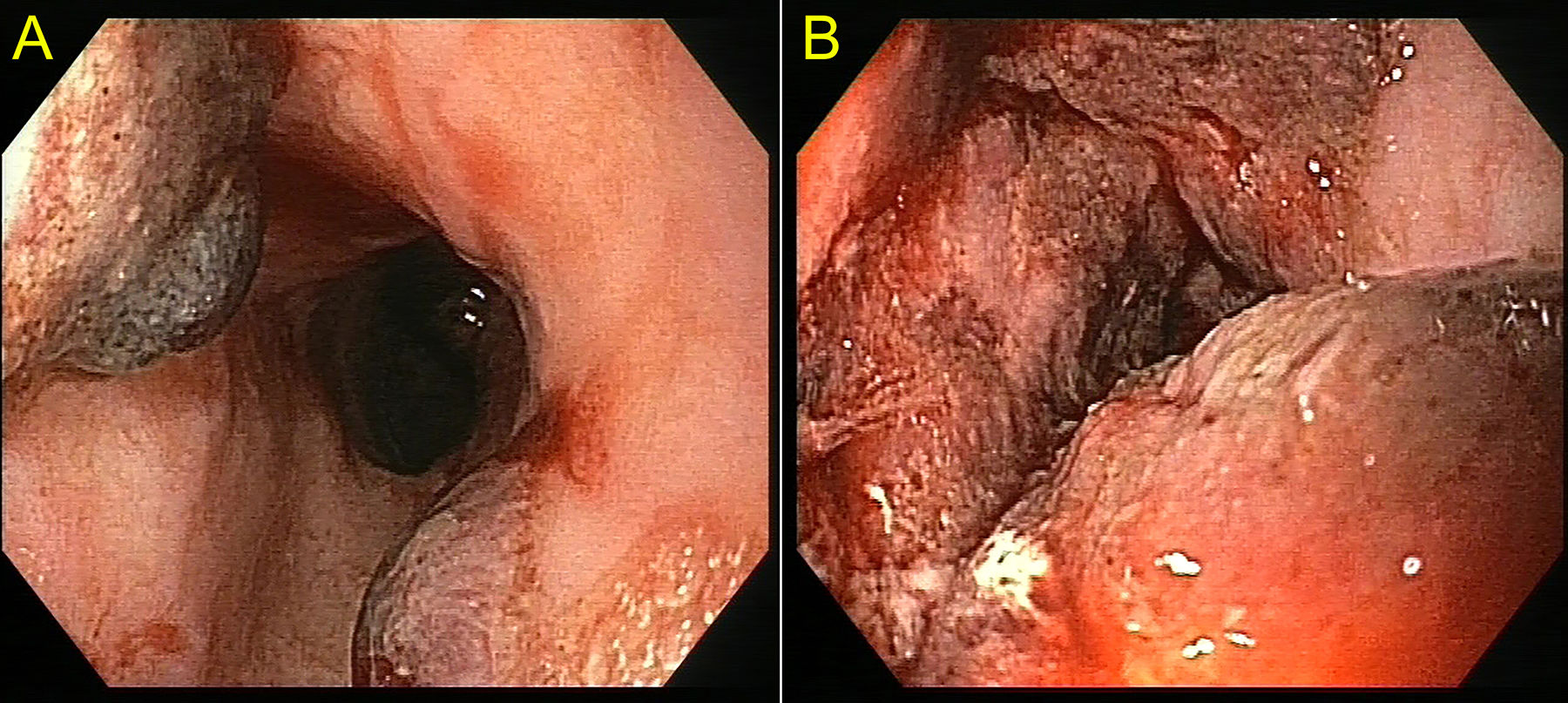

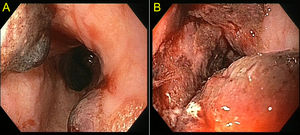

During her stay, the patient presented gradual development of anaemia (haemoglobin 12 mg/dl to 7 mg/dl; platelets 120 × 109/l; INR 1.2), melaena and an episode of haematemesis with no haemodynamic instability. A gastroscopy revealed multiple vesicles along the oesophagus measuring 10−20 mm (Fig. 1). In addition, the inferior third of the oesophagus presented ulcerated, friable mucosa with vesicles and fresh blood remnants (Image 1B). The oesophageal biopsies reported necrotic matter, calcifications and fibrinoleukocyte material. Given the simultaneous presence of ulcerated lesions in the oral cavity, empirical treatment was started with intravenous aciclovir. Seven days later, a repeat gastroscopy showed complete resolution of the lesions and a small varix in the distal third of the oesophagus. Subsequently, the results of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) performed on the patient’s blood at the onset of her signs and symptoms were received: the test was positive for cytomegalovirus. For the oesophageal samples, PCR was positive for cytomegalovirus and HSV type 1. An abdominal CT scan performed during the patient’s stay revealed an irregular liver parenchyma with lobulated contours and ascites.

The patient was discharged after a stay of 69 days without presenting any new complications secondary to infectious oesophagitis. She is being followed up for her chronic liver disease.

The main risk factors for infectious oesophagitis are HIV, organ transplant and use of chemotherapy drugs, immunosuppressants and corticosteroids.1,4

The most common symptom is odynophagia; gastrointestinal bleeding is very uncommon.1,5 However, concomitant infection with HSV and cytomegalovirus increases the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and perforation.2,3 This may be because the herpes infection is located in the epithelium of the oesophageal wall, whereas the cytomegalovirus infection affects mesenchymal cells, including the endothelial cells of the small blood vessels, in the deepest part of the oesophageal wall.3

In oesophagitis due to HSV, depending on the duration and severity of the infection, findings ranging from small vesicles on an erythematous base to multiple superficial or deep ulcers covered in yellowish exudate may be observed. Lesions are essentially located in the medial and distal oesophagus, and in immunosuppressed patients perforations secondary to necrotic oesophagitis may develop.1,2,4

Oesophageal ulcers due to cytomegalovirus are also located in the medial or inferior oesophagus. They are usually large and not very deep (though they sometimes have raised edges) and may be single or multiple.1,4

The diagnosis is made based on biopsies of oesophageal ulcers; the most sensitive method is PCR.3

Aciclovir, famciclovir or valaciclovir is used to treat oesophagitis due to HSV in immunosuppressed patients; ganciclovir, valganciclovir or foscarnet may be used to treat oesophagitis due to cytomegalovirus.1 Our patient required no additional treatment for cytomegalovirus as her lesions resolved rapidly with aciclovir.

In conclusion, although infectious oesophagitis is an uncommon cause of gastrointestinal bleeding, it must always be suspected in immunosuppressed patients given its variable clinical and endoscopic presentation and the possibility of resolution with empirical treatment.

FundingNone.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Ríos León R, Martín Mateos RM, Mateos Muñoz B, Albillos Martínez A. Hemorragia digestiva grave secundaria a esofagitis por virus del herpes simple y citomegalovirus. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:449–450.