Peritoneal tuberculosis is the most common form of abdominal tuberculosis and a common cause of ascites in endemic countries. Its incidence has increased in recent decades, as it is associated with states of immunosuppression. It may simulate spread to the peritoneum of advanced cancer in any location, which may result in extensive, unnecessary surgery.1

A 49-year-old woman originally from Cuba with a history of posterior uveitis and a good response to treatment with adalidumab, currently stable, was admitted for the second time in two months due to signs and symptoms of fever and right subcostal pain. Antibiotic treatment and naproxen were started; with that, the patient’s fever resolved.

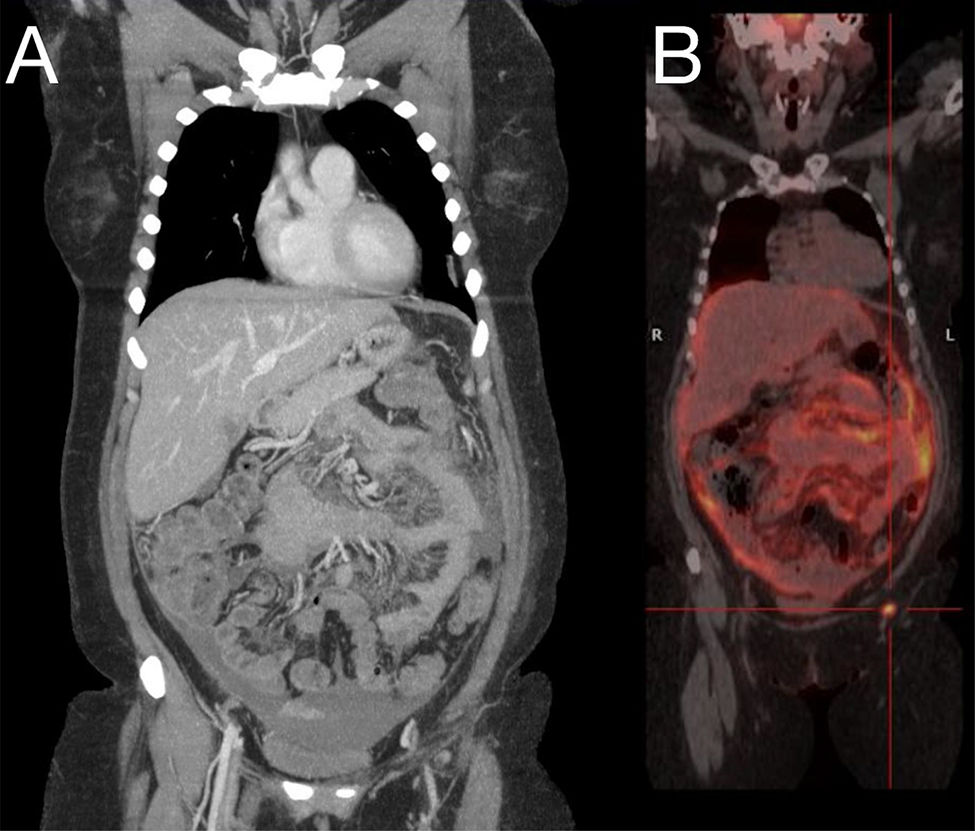

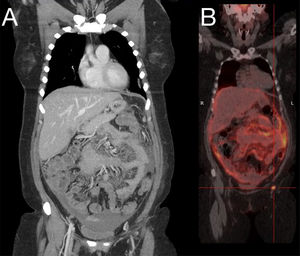

Physical examination revealed a cushinoid phenotype and pain on palpation of the right hypochondrium. Laboratory testing showed a normal liver panel and bilirubin; leukopenia (3100 leukocytes/dl); elevated tumour markers; beta-2 microglobulin 3.68 mg/l; Ca 125 528.2 U/mL; and neuron-specific enolase 24.6 ng/m. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was ordered. This scan found peritoneal carcinomatosis, moderate intra-abdominal ascites, pathological lymphadenopathy in the right cardiophrenic angle and countless bilateral lung micronodules. These findings were suggestive of tumour spread of an unknown primary neoplasm (Fig. 1A). The study was complemented and a PET/CT scan was performed, which confirmed the findings of peritoneal and hepatic pericapsular carcinomatosis with multiple instances of supra- and sub-diaphragmatic lymphadenopathy and probable pleural implants (Fig. 1B). A diagnostic paracentesis was performed and a sample was taken for ascitic fluid testing which was negative for malignant cells. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of a right subphrenic lymphadenopathy also was performed and also came back negative for malignancy. To attempt to identify the possible primary neoplasm, a gastroscopy and colonoscopy were performed. These revealed no significant abnormalities. A gynaecological examination and a mammogram were also done and yielded normal results.

A: CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis: peritoneal carcinomatosis, moderate intra-abdominal ascites, pathological lymphadenopathy in the right cardiophrenic angle and bilateral pulmonary micronodules. B: PET/CT scan: peritoneal and hepatic pericapsular carcinomatosis with multiple instances of supra- and sub-diaphragmatic lymphadenopathy and probable pleural implants.

Given the negative results of the examinations, a decision was made to perform an exploratory laparoscopy. This found a complete omental block with friable adhesions to the parietal peritoneum and the bowel, complicating dissection and causing bleeding when grazed. A full omental patch dissection was performed and the specimen was sent as a biopsy. Pathology confirmed findings of necrotising granulomatous peritonitis with acid–alcohol-fast bacilli, consistent with tuberculous disease.

The patient started treatment with isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol, and a Mycobacterium tuberculosis (MT) antibiogram revealed that the bacteria was resistant to these drugs. The patient’s antibiotic treatment was adjusted and treatment was started with levofloxacin, ethambutol, linezolid and capreomycin. After that, the patient reported improved pain and followed a favourable clinical course with subsequent follow-up for a year, with no onset of any new symptoms or relapses.

Tuberculosis has a global incidence of 2%, whereas the incidence of peritoneal tuberculosis ranges from 0.1% to 0.7%2 and is higher in developing countries. It generally develops as a result of haematogenous spread of a pulmonary focus or direct spread from adjacent organs, such as the bowel. Cirrhosis, peritoneal dialysis, diabetes mellitus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and use of immunosuppressants, especially TNF inhibitor drugs, are risk factors for peritoneal tuberculosis.3

Clinical symptoms and radiological findings in peritoneal tuberculosis are highly variable and non-specific, and they overlap with other diseases with very different prognoses and treatments, such as peritoneal carcinomatosis and Crohn’s disease. Hence, strong diagnostic suspicion is required.

Clinically, it is an insidious, disease with a long clinical course in which the most common signs and symptoms are fever, ascites, abdominal pain and weight loss.4

Most studies have suggested that CT does not distinguish between tuberculosis and peritoneal carcinomatosis,5 as in our case. Images such as peritoneal thickening and ascites are usually useful for diagnosis but may also overlap with other diseases.

Ascitic fluid testing is one of the diagnostic tests available for peritoneal tuberculosis. Ascitic fluid is usually an exudate, with lymphocytosis, but acid–alcohol-fast bacilli (AAFB) are detected in the culture in only 25% of cases. Adenosine desaminase (ADA) is the most commonly used biomarker to diagnose tuberculosis. A diagnosis of tuberculosis is generally accepted and, as a result, empirical antituberculous treatment is started in patients with consistent signs and symptoms. In this case, it was not tested, since this possibility was not clinically suspected.

As the yield of peritoneal fluid culture is usually low and MT grows slowly, the diagnosis generally requires a laparoscopic or laparotomic peritoneal biopsy.3

As part of the diagnostic study in patients with suspected peritoneal tuberculosis, surgical biopsy has a high diagnostic yield and in many cases is needed to hasten diagnosis, as well as treatment, thus reducing the disease’s morbidity and mortality.

Please cite this article as: González Sierra B, de la Plaza Llamas R, Ramia Ángel JM. Tuberculosis peritoneal que simula una carcinomatosis: a propósito de un caso. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:447–449.