(1) To evaluate the short- and long-term clinical outcomes of patients after colorectal stent placement and (2) to assess the safety and efficacy of the stents for the resolution of colorectal obstruction according to the insertion technique.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study which included 177 patients with colonic obstruction who underwent insertion of a stent.

ResultsA total of 196 stents were implanted in 177 patients. Overall, the most common cause of obstruction was colorectal cancer (89.3%). Ninety-two stents (47%) were placed by radiologic technique and 104 (53%) by endoscopy under fluoroscopic guidance. Technical success rates were 95% in both groups. Clinical success rates were 77% in the radiological group and 81% in the endoscopic group (p>0.05). The rate of complications was higher in the radiologic group compared with the endoscopic group (38% vs 20%, respectively; p=0.006). Among patients with colorectal cancer (158), 65 stents were placed for palliation but 30% eventually required surgery. The multivariate analysis identified three factors associated with poorer long-term survival: tumor stage IV, comorbidity and onset of complications.

ConclusionsStents may be an alternative to emergency surgery in colorectal obstruction, but the clinical outcome depends on the tumor stage, comorbidity and stent complications. The rate of definitive palliative stent placement was high; although surgery was eventually required in 30%. Our study suggests that the endoscopic method of stent placement is safer than the radiologic method.

1) Evaluar los resultados clínicos a corto y largo plazo de los pacientes después de la colocación de una prótesis a nivel colorrectal y 2) Evaluar la eficacia y la seguridad de las prótesis en la resolución de la obstrucción en función de la técnica de inserción.

MétodosEstudio de cohortes retrospectivo que incluyó 177 pacientes con obstrucción cólica que fueron tratados incialmente con colocación de prótesis.

ResultadosSe colocaron 196 prótesis en 177 pacientes. La causa más frecuente de obstrucción fue el cáncer colorrectal (89,3%). Noventa y dos prótesis (47%) se colocaron mediante técnica radiológica y 104 (53%) mediante endoscopia bajo guía fluoroscópica. Las tasas de éxito técnico fueron del 95% en ambos grupos. Las tasas de éxito clínico fueron del 77% en el grupo radiológico y del 81% en el grupo endoscópico (p>0,05). La tasa de complicaciones fue mayor en el grupo radiológico en comparación con el grupo endoscópico (38 vs. 20%, respectivamente; p=0,006). Entre los pacientes con cáncer colorrectal (158), 65 prótesis se colocaron con un fin paliativo, pero el 30% requirió finalmente cirugía. El análisis multivariante identificó 3 factores asociados a una peor supervivencia: estadio tumoral IV, comorbilidad y aparición de complicaciones.

ConclusionesLas prótesis pueden ser una alternativa a la cirugía urgente en la obstrucción colorrectal, pero el resultado clínico depende del estadio tumoral, de la comorbilidad y de las complicaciones de la prótesis. La tasa de colocación de prótesis paliativa definitiva fue alta; aunque en un 30% se requirió cirugía, finalmente. Nuestro estudio sugiere que el método de implantación con visión endoscópica es más seguro que el método radiológico.

Colorectal obstruction is an abdominal emergency associated with high mortality and morbidity rates. Large bowel obstructions results from intrinsic or extrinsic factors, with colorectal cancer (CRC) by far the most common cause.1,2 It is unclear whether stent or surgery is the most appropriate modality for managing colorectal obstruction.3,4 Several uncontrolled studies have suggested that the placement of self-expandable metal stent (SEMS) in malignant large bowel obstruction could improve patients’ clinical conditions before elective surgery, leading to a decrease in mortality, morbidity, and the number of colostomies.1,5–7 It may also allow accurate tumor staging and serve as permanent palliation, allowing patients with not resectable disease and short life expectancy or unacceptable surgical risk to avoid surgery.8–10 The role of SEMS for benign colonic lesions or extracolonic causes is not clear, as the majority of studies are case reports or case series.11,12

The technical success (TS) and clinical success (CS) rates of SEMS vary widely between studies.14 A recent meta-analysis reported a high mean success rate of 76.9% (46.7–100%).10 However, there are also potential disadvantages as major complications or uncertainty regarding long-term outcomes.2,15–18

Finally, there are essentially two different SEMS insertion techniques: radiologic (XR) and endoscopic under fluoroscopic guidance (ER). In both cases, SEMS are placed under fluoroscopic guidance, but endoscopic assistance is only used in the ER technique.13 However, very few studies have analyzed differences in the efficacy of these methods.

To address these issues, we aimed to asses: (1) the short and long term clinical outcomes, including survival, of patients after SEMS placement and factors that could impact such outcomes and (2) the safety and efficacy of the stents to resolve the obstruction according to the insertion technique used [XR or ER].

Patients and methodsPatientsThe Endoscopy Unit at University Clinical Hospital, Zaragoza, has used SEMS as a therapeutic option for patients with acute colonic occlusion (especially malignant obstruction) since January 2008. The Interventional Radiology Unit has also performed this procedure in this hospital since 1991. In our study, we included all patients with a SEMS implantation via XR between January 2002 and January 2010 that were registered in the Hospital database and all patients with a SEMS implantation via ER between January 2008 and January 2013. The characteristics of the SEMS of XR group were obtained from the medical histories and the characteristics of SEMS of ER group were collected from a proprietary database. Medical records of all patients were reviewed retrospectively. The study was terminated on September 2013 or upon the death of the patient, whichever occurred first. The vital status was confirmed by the medical records or via telephone contact when needed.

ProceduresAll patients provided informed consent before the placement of SEMS. All patients underwent at least an abdominal computed tomography scan prior to insertion of the stent to diagnose the cause of the obstruction and to perform tumor staging in patients with malignant obstruction.

In the ER group. Expert endoscopists performed SEMS placement with the same through-the-scope technique. A therapeutic endoscope was advanced until tumoral stricture was found. WallflexTM Colonic Stents (Boston Scientific), 6, 9 or 12cm in length and 2.5cm in diameter, were used in most patients. HanarostentsTM Esophagus stents (M.I. Tech.) were used in two patients. Image intensification was used during the endoscopic placement. Biopsies were taken from the lesion when possible.

In the XR group. An expert interventional radiologist4,13 worked with two types of stents: the WallstentTM (Boston Scientific), 5–9cm in length and 1.6–2.5cm in diameter and SX-ELLA intestinal stent (Ella), 8.2–11.2cm in length and 2.2–3cm in diameter. The most appropriate size was chosen after visualization with fluoroscopy of the stenosis.

DefinitionsTechnical success (TS) was defined as a successful SEMS insertion with correct deployment and precise positioning of the SEMS at the location of the stenosis. The expert endoscopist or radiologist determined the TS of stent placement after radiological confirmation. Clinical success (CS) was defined as successful colonic decompression with disappearance of obstructive symptoms within 72h of stent placement. Complications were defined as any adverse event related to SEMS placement, leading to new symptoms, re-intervention, patient hospital readmission or death. Migration, re-obstruction, perforation, failure to expansion, long-term clinical failure, bleeding and fecal incontenence were considered complications. Long-term clinical failure was considered when the patient had recurrence of colorectal obstructive symptoms, but it was not possible to determine which was the specific cause (reobstruction, migration, tumor growth, etc.).

Statistical analysesAn initial exploratory analysis of all clinical variables was carried out. Continuous variables were expressed as the mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range (IQR); whereas, qualitative variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. The relationship between qualitative variables was evaluated with the Chi-square (χ2) test. Student's t-test or Mann–Whitney U test were employed for comparing means of two independent groups. Normality was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Overall survival (OS) time was calculated from the date of the diagnosis to the date of last contact or death from any cause. In addition, the comorbidities of patients at hospital admission were evaluated using a previously validated adaptation of the Charlson Comorbidity Index.19 Survival among different factors was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the Log rank test. Variables shown by univariate analysis to be significantly associated with survival were entered into a Cox proportional hazards regression model for multivariate analysis. For all tests, a two-sided p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software v22.0 for Windows was used for performing statistical analyses.

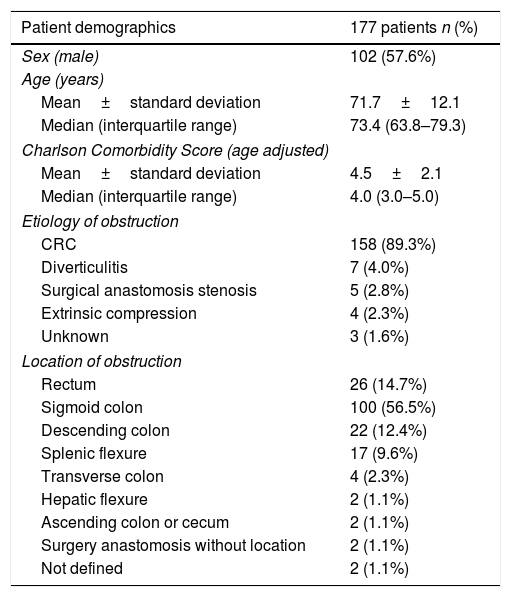

ResultsPatients demographicsA total of 196 SEMS were placed in 177 patients. Baseline data for these patients are summarized in Table 1. Males comprised 57.6% of the cohort, the median age was 73.5 (IQR: 63.8–79.3) years and the median age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity score was 4.0 (IQR: 3.0–5.0). Obstruction was distal to splenic flexure in 83% of patients. One patient presented obstruction in two different locations due to synchronous CRC. The most common cause of obstruction was primary CRC (89.3%). In patients with CRC, tumor stage was known in 142 patients and was stage IV in 51.4% (73/142). In patients with synchronous CRC, the most advanced CRC stage was chosen. The demographics of patients with CRC included in our study are shown in Table 2.

Demographics of patients with SEMS implantation.

| Patient demographics | 177 patients n (%) |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 102 (57.6%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean±standard deviation | 71.7±12.1 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 73.4 (63.8–79.3) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score (age adjusted) | |

| Mean±standard deviation | 4.5±2.1 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) |

| Etiology of obstruction | |

| CRC | 158 (89.3%) |

| Diverticulitis | 7 (4.0%) |

| Surgical anastomosis stenosis | 5 (2.8%) |

| Extrinsic compression | 4 (2.3%) |

| Unknown | 3 (1.6%) |

| Location of obstruction | |

| Rectum | 26 (14.7%) |

| Sigmoid colon | 100 (56.5%) |

| Descending colon | 22 (12.4%) |

| Splenic flexure | 17 (9.6%) |

| Transverse colon | 4 (2.3%) |

| Hepatic flexure | 2 (1.1%) |

| Ascending colon or cecum | 2 (1.1%) |

| Surgery anastomosis without location | 2 (1.1%) |

| Not defined | 2 (1.1%) |

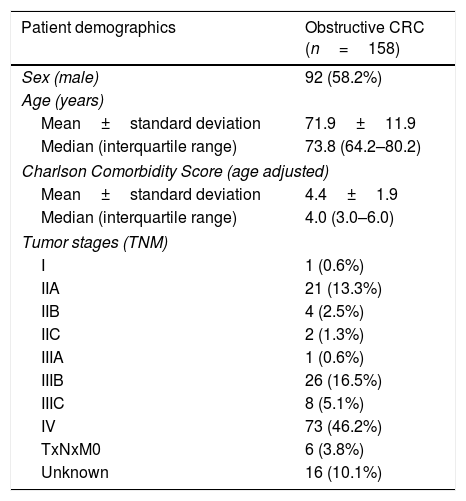

Demographics of patients with obstructive CRC.

| Patient demographics | Obstructive CRC (n=158) |

|---|---|

| Sex (male) | 92 (58.2%) |

| Age (years) | |

| Mean±standard deviation | 71.9±11.9 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 73.8 (64.2–80.2) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Score (age adjusted) | |

| Mean±standard deviation | 4.4±1.9 |

| Median (interquartile range) | 4.0 (3.0–6.0) |

| Tumor stages (TNM) | |

| I | 1 (0.6%) |

| IIA | 21 (13.3%) |

| IIB | 4 (2.5%) |

| IIC | 2 (1.3%) |

| IIIA | 1 (0.6%) |

| IIIB | 26 (16.5%) |

| IIIC | 8 (5.1%) |

| IV | 73 (46.2%) |

| TxNxM0 | 6 (3.8%) |

| Unknown | 16 (10.1%) |

CRC: colorectal cancer.

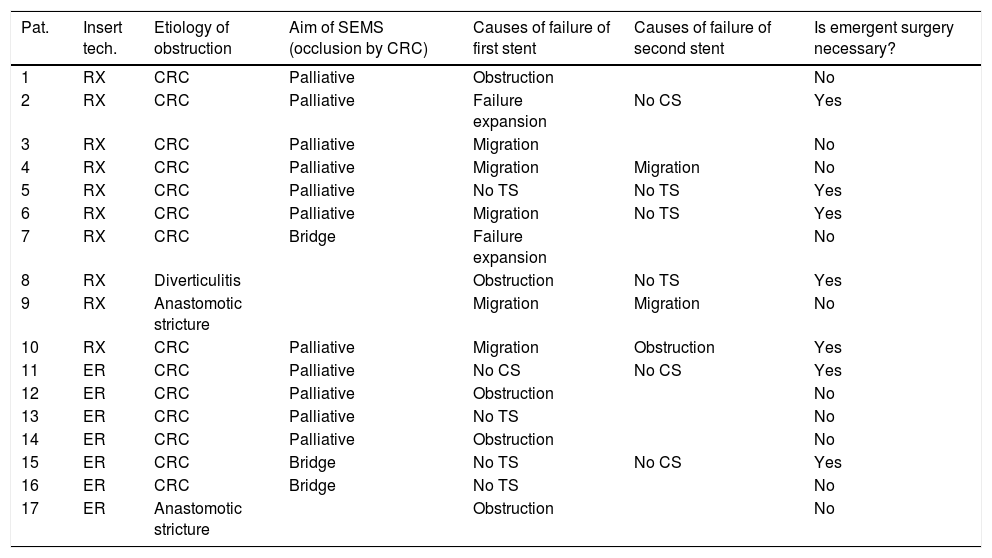

Ninety-two (46.9%) SEMS were placed by the XR technique and 104 (53.1%) by the ER method. The TS rates were 95.7% (88/92) for SEMS placed by XR and 95.2% (99/104) for those placed by ER (p=0.87). The CS rates were 77.3% (68/88) and 80.8% (80/99) for the XR and ER groups, respectively (p=0.27). The CS was unknown in 5 patients who were lost to follow-up and attended different hospitals. The rate of complications was higher with XR placement than ER (38.0% vs 20.2%; p=0.006). In the XR group, there were 35 complications: 13 migrations of SEMS, 8 re-obstructions, 8 perforations, 2 failures of expansion of SEMS, and 4 patients with severe rectal symptoms. In the ER group, there were 21 complications: 4 migrations, 6 re-obstructions, 5 perforations, 2 long-term clinical failures, 1 pneumoperitoneum without objectified perforation, 2 failures of expansion, and 1 patient with severe rectal symptoms. Seventeen patients underwent a second SEMS placement attempt after an initial clinical or technical failure (Table 3).

Use of a second SEMS.

| Pat. | Insert tech. | Etiology of obstruction | Aim of SEMS (occlusion by CRC) | Causes of failure of first stent | Causes of failure of second stent | Is emergent surgery necessary? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Obstruction | No | |

| 2 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Failure expansion | No CS | Yes |

| 3 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Migration | No | |

| 4 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Migration | Migration | No |

| 5 | RX | CRC | Palliative | No TS | No TS | Yes |

| 6 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Migration | No TS | Yes |

| 7 | RX | CRC | Bridge | Failure expansion | No | |

| 8 | RX | Diverticulitis | Obstruction | No TS | Yes | |

| 9 | RX | Anastomotic stricture | Migration | Migration | No | |

| 10 | RX | CRC | Palliative | Migration | Obstruction | Yes |

| 11 | ER | CRC | Palliative | No CS | No CS | Yes |

| 12 | ER | CRC | Palliative | Obstruction | No | |

| 13 | ER | CRC | Palliative | No TS | No | |

| 14 | ER | CRC | Palliative | Obstruction | No | |

| 15 | ER | CRC | Bridge | No TS | No CS | Yes |

| 16 | ER | CRC | Bridge | No TS | No | |

| 17 | ER | Anastomotic stricture | Obstruction | No |

Pat: patient; Insert tech: insertion technique; SEMS: self expandable metal stent; CRC: colorectal cancer; CS: clinical success; TS: technical success; RX: radiologic; ER: endoscopic under fluoroscopic guidance.

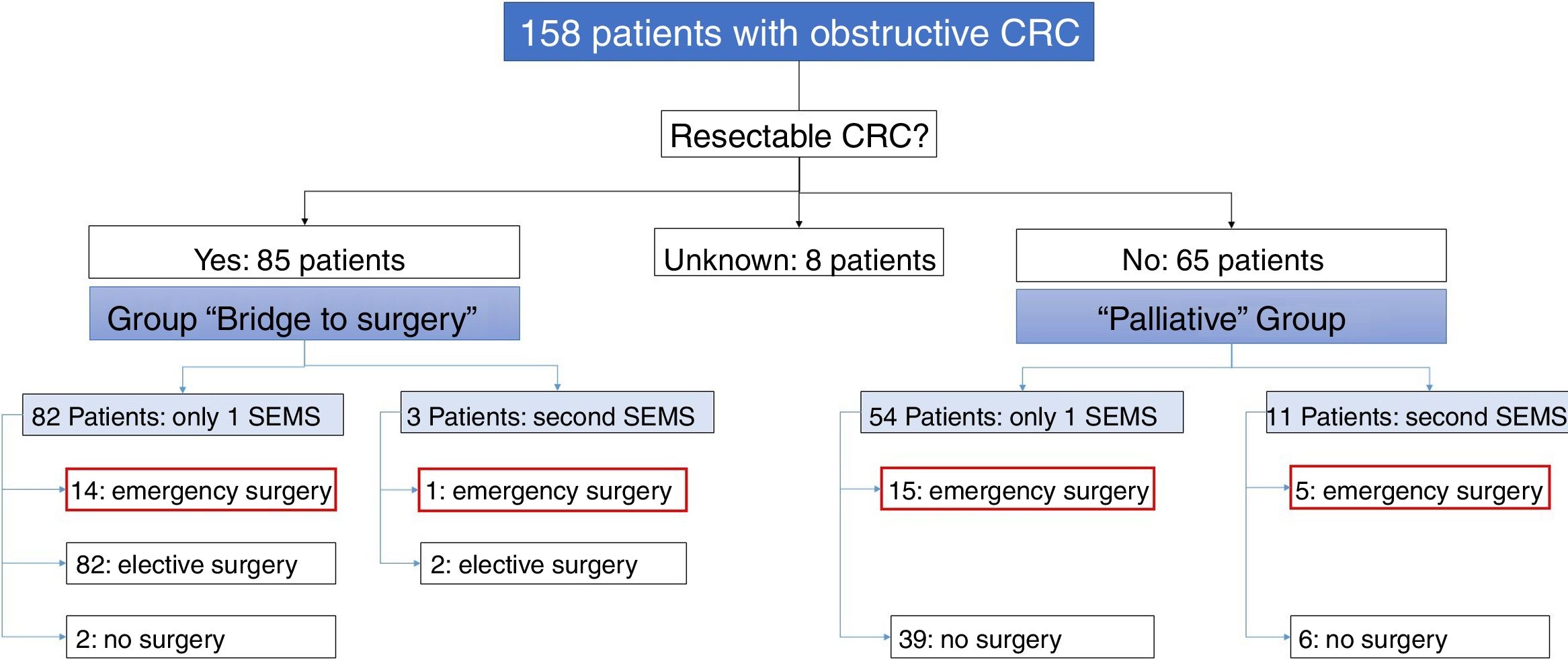

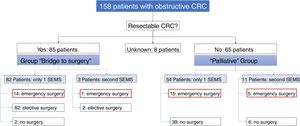

Of the 158 patients with CRC, 85 SEMS were inserted as a “bridge to surgery” and 65 SEMS were placed in patients with non-resectable tumors (“palliative” group). In the “bridge to surgery” group, 37 (43.5%) SEMS were inserted by the XR technique and 48 (56.5%) by ER method. The indication for SEMS placement, “bridge to surgery” or “palliation” was determined by the most responsible physician based on the stage of the tumor, the age and the comorbidity of the patient. Eight patients were submitted from other centers and the indication for SEMS placement was not recorded (see Fig. 1).

- 1)

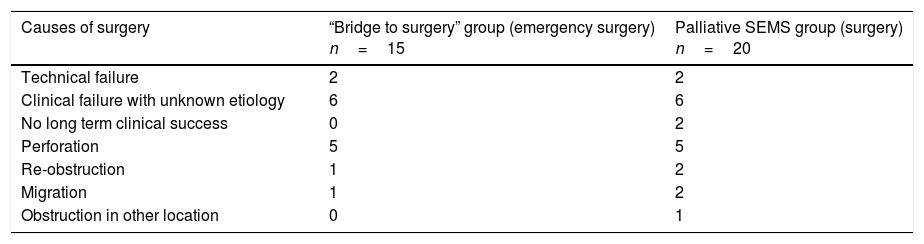

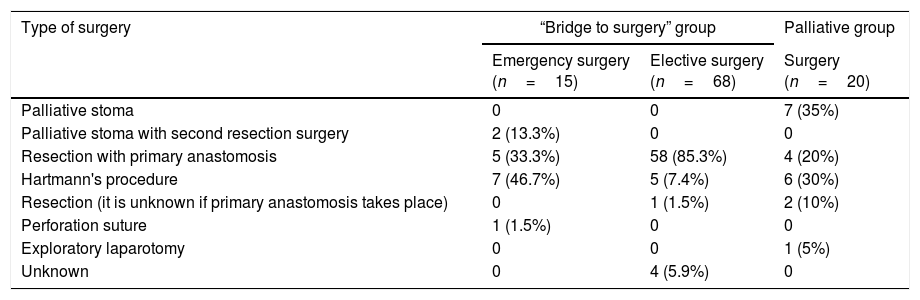

“Bridge to surgery” Group. The TS and short-term CS rates were 96.5% (82/85) and 86.6% (71/82), respectively. Three patients were reevaluated and additional SEMS were implanted (see Table 3). Emergency surgery was carried out in 15 (17.6%) patients and elective surgery in 68 patients (80%). Two patients did not undergo surgery. A resection with primary anastomosis could be done in 58 of the elective surgeries (85.3%) and in only 5 of emergency surgeries (33.3%), p<0.001. Thus, a stoma was not needed in 63 patients (76%). After excluding emergency surgeries, the mean time to surgery was 32.1 days (95%CI: 15.7–48.4) (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.Causes of non-elective surgery after SEMS placement.

Causes of surgery “Bridge to surgery” group (emergency surgery)

n=15Palliative SEMS group (surgery)

n=20Technical failure 2 2 Clinical failure with unknown etiology 6 6 No long term clinical success 0 2 Perforation 5 5 Re-obstruction 1 2 Migration 1 2 Obstruction in other location 0 1 SEMS: self expandable metal stent.

Table 5.Type of surgery.

Type of surgery “Bridge to surgery” group Palliative group Emergency surgery

(n=15)Elective surgery

(n=68)Surgery

(n=20)Palliative stoma 0 0 7 (35%) Palliative stoma with second resection surgery 2 (13.3%) 0 0 Resection with primary anastomosis 5 (33.3%) 58 (85.3%) 4 (20%) Hartmann's procedure 7 (46.7%) 5 (7.4%) 6 (30%) Resection (it is unknown if primary anastomosis takes place) 0 1 (1.5%) 2 (10%) Perforation suture 1 (1.5%) 0 0 Exploratory laparotomy 0 0 1 (5%) Unknown 0 4 (5.9%) 0 - 2)

Palliative SEMS Group. The TS and short-term CS rates were 95.4% (62/65) and 80.6% (50/62), respectively in this group. Eleven patients had endoscopic or radiological re-intervention and additional SEMS were implanted (Table 3). Twenty (30%) patients required surgery due to technical or clinical failure or SEMS complications (Tables 4 and 5).

The median follow-up of patients with obstructive CRC (after SEMS placement) was 14.6 months (range: 0.10–141.8). The median survival of patients with obstructive CRC, with a SEMS implanted, was 18.6 months (95%CI: 13.3–23.9); whereas, the median survival of patients with a SEMS implanted for palliative care was 3.1 months (95%CI: 0.3–6.0).

Prognostic factors that independently impacted on survival in patients with obstructive CRC and a SEMS implanted, by univariate analysis were: Charlson index>4 [HR: 2.51 (95%CI: 1.71–3.70)], age>73 years [HR: 2.10 (95%CI: 1.44–3.09)], tumor stage IV [HR: 3.27 (95%CI: 2.16–4.95)], no CS [HR: 2.46 (95%CI: 1.52–4.00)], presence of complications [HR: 1.93 (95%CI: 1.22–3.06)] and a prolonged time to surgery after SEMS placement [HR: 1.006 (95%CI: 1.002–1.010)]. However, neither insertion technique [HR: 1.15 (95%CI: 0.79–1.67)] nor TS [HR: 1.32 (95%CI: 0.48–3.58)] was related to survival.

Multivariate analysis of the significant variables determined by univariate analysis identified tumor stage IV [HR: 4.78 (95%CI: 2.84–8.04)], Charlson index>4 [HR: 1.97 (95%CI: 1.06–3.63)] and presence of SEMS complications [HR: 1.75 (95%CI: 1.06–2.90)] as factors related with survival in our cohort of patients.

DiscussionEndoluminal decompression by stent insertion may be an alternative to emergency surgery in colorectal obstruction. In patients with obstructive CRC, SEMS can be used as a “bridge to surgery” if CRC is potentially resectable, or as palliative treatment in patients with disseminated disease or unacceptable surgical risk. In our series, the TS and CS rates of SEMS were 95.4% and 79%, respectively, similar to those reported in a recent meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (mean success rate 76.9%)10 and lower than those reported in a recent systematic review of 88 studies (96.2% and 92%, respectively).14 Major complications of our series were migrations (8.6%), re-obstruction (7.1%), and perforation (6.6%). Our migration rate is lower than the median rate reported by Watt et al. in their systematic review including 54 studies (11%)14 and also lower than reported by Khot et al. in technically successful cases (10%).20 However, our rate of perforations is slightly higher than data reported from previous studies. Datye et al., in their article that included a total of 2287 patients, found an overall perforation rate of 4.9%21 and Watt et al. showed a median rate of 4.5%.14 This difference could be explained by our study including, not only perforations produced by the stent itself, but also perforations secondary to distension that occurred in patients with clinical failure after the procedure. Finally, our re-obstruction rate is lower than the mean rate reported in the review by Khot et al. (10%).20

The SEMS can be placed using ER or XR. However, very few studies have analyzed if there are differences in the efficacies of these methods. In a recent retrospective study comparing both procedures, ER was more successful than XR method (90.3% vs 74.8%, p<0.001).22 In another retrospective study, Kim et al. showed that while the TS rate was significantly higher with the ER than XR (100% vs 92.1%, p=0.038), the CS rates were similar with the two insertion techniques (91.8% vs 97.1%, p>0.05).23 In our study, the TS and CS rates were similar in both groups (p>0.05). However, the complications rate was significantly higher when using XR placement compared with ER (38% vs 20.2%; p=0.006). We found a significantly higher number of migrations. It could be speculated that an indirect visualization during the SEMS release could result in a misplacement of the device, even in expert hands.4,13 These data and those previously published suggest that the ER method is the preferred technique. One of the limitations of our study is that we compared both procedures but in different time frames. It could condition certain biases mainly due to the evolution in the treatments directed to CRC in these years.

There is significant controversy regarding the best surgical treatment and the role of SEMS in obstructive CRC. Urgent surgery in these patients is associated with high morbidity and mortality rates (30–60% and of 7–22%, respectively), both significantly higher than those observed in elective surgery.2 If the goal of “bridge to surgery” stenting is to decrease the stoma rate, our study suggests that SEMS placement is an acceptable option. In fact, in 76% of patients, a single-stage surgery intervention was achieved in the “bridge to surgery” group and Hartmann's procedure was done in only 14.5% of patients. Our data are consistent with previous data that showed success rates for one-stage elective operation of 60–85% when SEMS were used as a bridge to surgery.24–27 There is also interest regarding the role of SEMS for palliative care. In such cases, the duration of palliation is critical. In our series, among patients in which SEMS were placed for palliation, only 70% maintained relief of obstruction until death or the end of the follow-up period. These results suggest that SEMS could be useful in this setting; although, all available options should be carefully discussed with the patient. The implantation of SEMS for palliative purposes can improve quality of life of patients with relative low rates of early complications. But, because the long-term outcomes of SEMS insertion continue to be a matter of controversy, surgical treatment can be taken into account in patients with a long life expectancy or suitables for chemotherapy. More studies regarding the quality of life after definitive SEMS placement and the cost-effectiveness of this strategy should be carried out before a definitive conclusion can be made.

Finally, very few studies have assessed which factors may influence the survival of patients treated with a SEMS. We performed a survival analysis and the OS time was determinated from the date of the diagnosis to the date of death of patient from any cause or last contact. In our study, multivariate analysis identified three prognostic factors that independently impacted on survival in our cohort of patients: tumor stage IV, Charlson index>4 and presence of complications. Older age, comorbidity, and advanced tumor stage are well known co-related factors, since older patients frequently present more comorbidities and age is the most significant risk factor for colorectal carcinogenesis. A larger sample size would be necessary to confirm if other variables such as the time to surgery or clinical failure are risk or confounding factors.

To our knowledge, the present study represents one of the largest cohorts of patients with colorectal obstruction and SEMS placement. We demonstrated that SEMS implantation is a feasible alternative to colostomy in acute colorectal occlusion. However, it has pros and cons and is far from being the perfect alternative. The rate of patients requiring surgery after a definitive (at least in theory) palliative SEMS placement is too high (30%) from our perspective. Although, SEMS placement can decrease the number of patients needing a stoma when used as a “bridge to surgery”. Survival of patients after SEMS placement depends on tumor stage, comorbidity and stent complications. In addition, our results suggest that SEMS placement by ER may be safer than the XR method and may be the method of choice, although this needs to be confirmed in other larger studies.

Author's contributionsAll authors meet the three required conditions: a. Substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; b. Drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; c. Final approval of the version to be published.

Financial supportThe present investigation has not received any specific grant from agencies of the public, commercial, or non-profit sectors.

Conflict of interestThe authors have no conflict of interest regarding this paper.

To our patients, who continuously teach us so many things.