With an increase of prescription medication and herbal supplemental use, drug induced liver injury (DILI) has become progressively a more important entity when considering acute hepatitis aetiology. The unpredictable fashion and low frequency of idiosyncratic DILI, along with the highly variable clinical scenerios it can assume, turns DILI into an under-recognised event. Therefore, clinical suspicion, thorough medical history and many a time confirmatory histology remain the most relevant clues for diagnosis and imputability.

Tibolone is a synthetic oestrogen commonly used to minimize menopause symptoms. It is usually well tolerated and liver toxicity has been previously reported only in three occasions.1–3 The authors report a case of tibolone acute hepatitis with cytolytic pattern.

A 45-year-old female was referred to the Hepatology Clinic because of abnormal liver function tests. She was asymptomatic and denied fever, rash, anorexia or malaise. The physical examination was unremarkable: no jaundice, no scratch lesions, liver and spleen were not palpable. She had no history of alcohol intake and denied over the counter use of drugs or herbal products. She also denied extramarital sexual contacts and recent travels abroad.

In her medical history, she pointed out that due to menopausal symptoms, she had been prescribed, 6 months earlier, with tibolone 2.5mg, which she has been taking regularly. Just before starting, she had a complete blood count and liver function tests with normal profile. She presented now with asymptomatic rise of ALT and AST (600UI/mL and 280UI/mL, respectively) and GGT of 400UI/mL, with normal ALP. Coagulation tests were normal as bilirubin and lipid profile. Abdominal ultrasonography showed no hepatomegaly, biliary duct dilation or portal vein thrombosis. Serology for hepatitis A, B and C virus, Epstein–Barr virus, Herpes simplex virus and Cytomegalovirus yielded negative results. Also, hepatitis B DNA, hepatitis C and hepatitis E RNA were undetectable on polymerase chain reaction. Testing for primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis did not reveal autoantibodies. Iron and copper studies were normal.

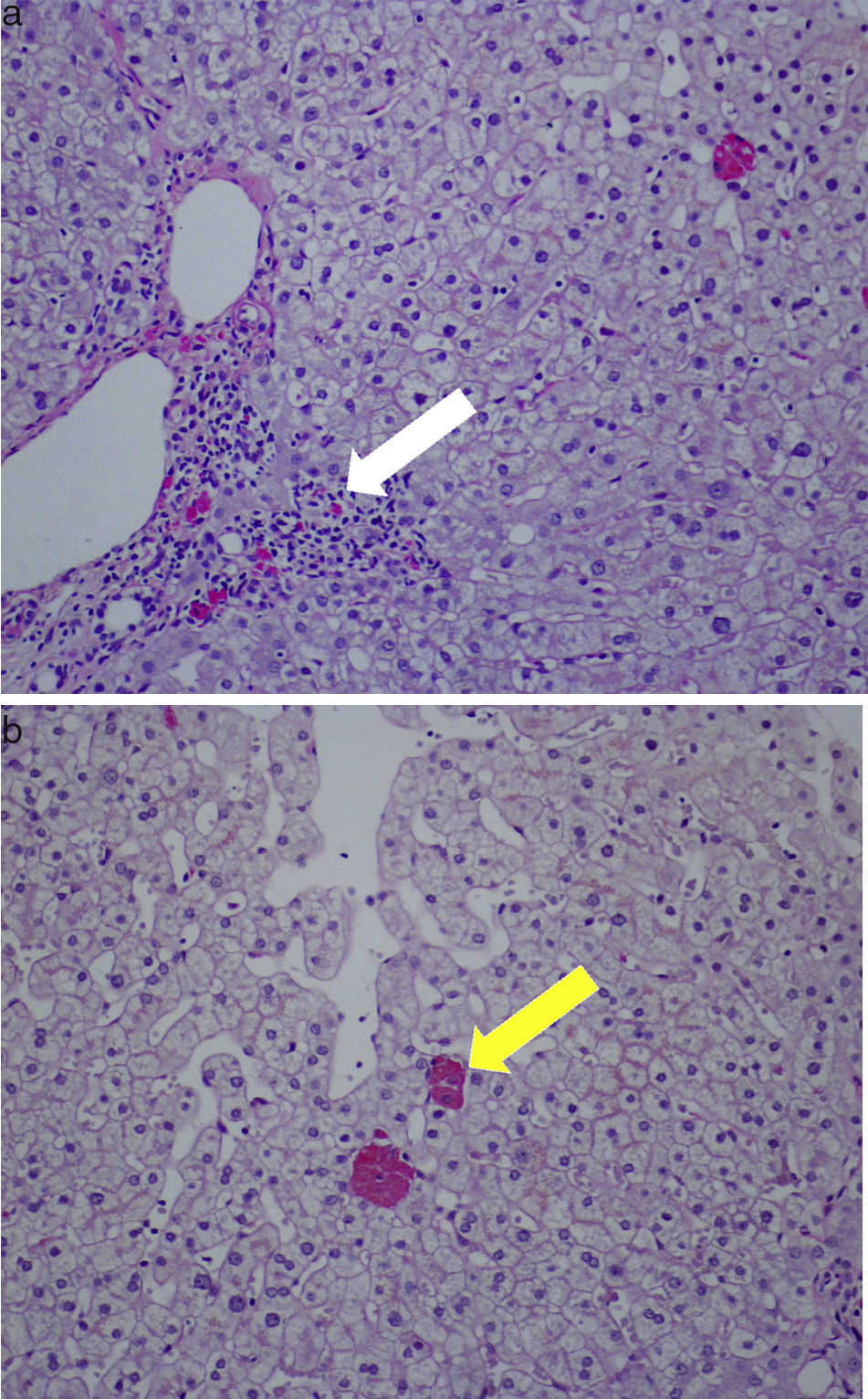

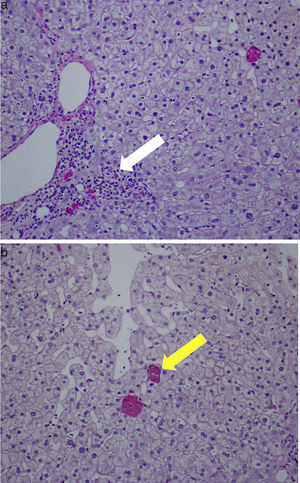

Therefore a percutaneous liver biopsy was performed and showed preserved architecture, portal necroinflammatory lesions and ceroid-like pigments accumulation in macrophages. These lesions of non-specific hepatitis were compatible with drug induced injury (Fig. 1). Tibolone-induced liver injury was suspected and the drug was discontinued.

After tibolone discontinuation, liver tests went back to normal in less than 3 weeks. The RUCAM scale summed a total of 9 points, suggesting DILI from Tibolone was highly probable.

There is no hallmark test or a specific marker for the diagnosis of DILI. Routine biochemical tests, serologic markers, tissue biopsy and liver imaging are usually the first battery of investigations conducted to identify causes of (acute) liver disease.

There are 3 patterns of DILI: hepatocellular, cholestatic and mixed. In the first one, there is a predominant cytolytic injury resulting in elevation of serum transaminases before jaundice. Cholestatic injury is defined as a R-value (elevation of ALP greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal and/or the ratio of serum ALT/serum activity of ALP)<2.4 An R-value ranging from 2 to 5 characterizes mixed DILI and a R-value>5 it characterizes hepatocellular DILI (our patient had a R-value=12).4

Although not mandatory in every case, a liver biopsy may become essential in cases of acute on chronic liver failure to estimate underlying fibrosis and to assess the chance of recovery versus the need for liver transplant. Histology is also important for establishment of causality in some acute lesions, many times helping to rule out other causes of liver disease.5 In a series of 83 consecutive patients with non-viral clinical acute hepatitis syndrome, 18% were due to drug induced liver lesions.6

Although consensus expert opinion following a thorough evaluation for competing etiologies is the current gold standard for establishing causality in individuals with suspected DILI, is not widely available and therefore it is not recommended for clinical practice.4 The RUCAM scale is an instrument to facilitate the causality attribution for suspected DILI. Scores are often grouped into likelihood levels of “excluded” (score≤0), “unlikely” (1–2), “possible” (3–5), “probable” (6–8), and “highly probable” (>8).4 RUCAM is useful in providing a diagnostic framework upon which to guide an evaluation in patients with suspected DILI, however, it should not be used as the sole diagnostic tool in isolation owing to its suboptimal retest reliability and lack of robust validation.

Tibolone is a 19-nortestosterone derivative with a weak androgenic effect, and a synthetic steroid analogue for the treatment of postmenopausal climacteric symptoms.7 Tibolone, like most steroids, is extensively metabolized in the liver.8

Only three cases have been reported relating tibolone with liver injury: in one, acute cholestatic liver damage occurred in a patient with UGT1A mutation, while undergoing therapy with concomitant flavoxate for urinary incontinence;1 another patient developed acute hepatitis with prolonged cholestasis and vanishing bile duct syndrome, but with concomitant use of St John's wort infusions, making probable an interaction between the herbal preparation and tibolone.2 The only case with exclusive tibolone involvement had a cholestatic pattern, with no histology available supporting this aetiology.3

The fact that our patient had no previous history of liver disease, the negative complementary study and the rapid normalization of liver tests after drug discontinuation, together with the supporting histological proof of toxicity, support the diagnosis of DILI. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case of tibolone acute hepatitis with cytolytic pattern.

Despite advances in the understanding and in assessing causality in DILI, it is necessary to rely heavily on clinical judgement and expert input when making decisions regarding the likely cause of an acute liver injury.9 A thorough examination of the circumstances of the liver injury include: defining a clear time of onset (latency) and response to withdrawal, confirming the absence of risk factors predisposing to other possible causes and using histology in unpredictable and/or unclear cases. All these strategies are the main tools to corroborate a high index of suspicion and to define, as in this case, the causality of a drug induced liver injury.

Acknowledgments and potential conflicts of interestNone declared.