Measurement of patient-perceived outcomes in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) care is becoming increasingly important. A simple and validated tool exists in English for this purpose, the “IBD-Control”. Our aim is to translate it into Spanish, adapt and validate it.

Patients and methodsThe IBD-Control was translated into the Spanish instrument “EII-Control” and prospectively validated. Patients completed the EII-Control and other questionnaires that served as baseline comparators. The gastroenterologist performed a global assessment of the disease, calculated activity indices and recorded treatment. A subgroup of patients repeated the entire assessment at a second visit. The usefulness of IBD-Control summary scales (IBD-Control-8 and IBD-Control-VAS) was also analysed.

ResultsA total of 249 IBD patients were included (101 repeated the second visit). Psychometric standards of the test: internal consistency: Cronbach’s α for EII-Control 0.83 with strong correlation between EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA (r = 0.5); reproducibility: intra-class correlation 0.70 for EII-Control; construct validity: moderate to strong correlations between IBD-Control, IBD-Control-8 and IBD-Control-VAS versus comparators; discriminant validity: P < .001; sensitivity to change: same response as quality of life index. Sensitivity and specificity at cut-off point 14 of 0.696 and 0.903, respectively, to determine quiescent status.

ConclusionsThe IBD-Control is a valid instrument to measure IBD-Control from the patient’s perspective in our environment and culture. Its simplicity makes it a useful tool to support care.

La medida de los resultados percibidos por el paciente (PROM) en la asistencia de la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) adquiere cada vez más importancia. Existe una herramienta sencilla y validada en inglés para este fin, el “IBD-control”. Nuestro objetivo es traducirlo al español, adaptarlo y validarlo.

Pacientes y métodosSe tradujo el IBD-control generando el instrumento en español ‘EII-Control’ y se validó prospectivamente. Los pacientes cumplimentaban el EII-Control y otros cuestionarios que servían de comparadores de referencia. El gastroenterólogo realizaba una valoración global de la enfermedad, calculaba índices de actividad y registraba el tratamiento. Un subgrupo de pacientes repitió toda la valoración en una segunda visita. Se analizó también la utilidad de escalas resumidas del EII-Control (el EII-control-8 y el EVA-EII-control).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 249 pacientes con EII (101 repitieron la segunda visita). Estándares psicométricos del test: Consistencia interna: α de Cronbach para EII-control 0,83 con fuerte correlación entre EII-Control-8 y EII-Control-EVA (r = 0,5). Reproductibilidad: correlación intraclase = 0.70 para EII-Control. Validez de constructo: correlaciones de moderadas a fuertes entre EII-control, EII-Control-8 y EVA-EII-Control frente a comparadores. Validez discriminante: P <,001. Sensibilidad al cambio: misma respuesta que índice de calidad de vida. Sensibilidad y especificidad en el punto de corte 14 de 0,696 y 0,903 respectivamente para determinar el estado quiescente.

ConclusionesEl EII-Control es un instrumento válido para medir el control de la EII desde la perspectiva del paciente en nuestro medio y cultura. Su simplicidad lo convierte en una herramienta útil para apoyar la asistencia.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic condition of the gastrointestinal tract that comprises two main conditions, Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), as well as indeterminate or unclassifiable colitis, which is much less common.1–3 IBD usually presents with periods of activity and remission. When the disease is active, the predominant clinical signs in CD are abdominal pain and diarrhoea, whereas in UC they are diarrhoea and rectal bleeding.1,2 These symptoms have a very negative impact on patients' lives, with an intrinsic subjective individual component that is important (perceived quality of life [QoL]). From this context arise the concepts of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) and patient-reported outcome measurement (PROM) as an evaluation of their own performance status and well-being.

A very important objective in treating IBD is achieving and maintaining symptom management to improve and ideally normalise QoL. Therefore, evaluation of the management of IBD from the patient's perspective is a fundamental matter in a great deal of treatment decision-making. This accounts for the growing interest in measuring PROs on the part of clinicians as well as regulatory agencies and health authorities.4,5 Thus, PROs are currently systematically included in the evaluation of new treatments, along with the most classic assessments (clinical indices, laboratory parameters, biomarkers and endoscopy).6–8 It is worth insisting that indices and clinical variables are not objectives and do not evaluate the patient's perspective on the impact that the disease has thereon,9 although PROs do. They have also started to play a role in audits and national registries.4 Standardised, validated questionnaires are available to evaluate PROs. They were largely developed in the past decade, and have given rise to the development of multi-domain PROM, both disease-specific (symptoms) and general (well-being, energy and vitality as well as impact on physical, social and emotional spheres).10–16

As these instruments are used more and more every day in clinical trials,11,15 interest is growing in their ability to supply information for individual practical care. However, they are not yet used on a regular basis in day-to-day practice. One reason may be the burden that the use of long multi-domain questionnaires would place on the time of patients and healthcare professionals. It is natural to think that abridged questionnaires, should they prove useful, could be incorporated into clinical practice.17,18 The ideal instrument should be simple to fill in and interpret, and it should add significant value to practical care. It should be reliable (accurate in measuring) and valid (capable of measuring what it was designed to measure). Such a tool could represent an advance in real treatment personalisation.

To this end, Bodger et al. developed and validated a questionnaire in the United Kingdom, called the “IBD-Control”, intended to quickly capture IBD management from the patient's perspective.19 It was designed to be brief, simple to fill in and interpret, as well as to have “generic” content, for purposes of maximising its potential practical use in a broader spectrum of patients with IBD.

The usefulness of this index for clinical practice is obvious, but it is highly advisable to formally validate it in other populations with IBD before recommending its use. There is no similar instrument in Spanish. The objective of our study was to translate into Spanish and validate the use of the IBD-Control in our setting in order to produce the first PROM questionnaire translated into and validated in Spanish, which could be used in research and clinical practice.

MethodologyThe objective of our study was to translate into Spanish the IBD-Control (“EII-Control” in Spanish) and demonstrate its reliability, validity and sensitivity in measuring IBD management, both in UC and in CD in our setting (understood as a language and a culture). The process and methodology replicate, outside of minimal deliberate differences, those carried out with the original index.

Our IBD unit at Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet [Miguel Servet University Hospital] provides both outpatient and inpatient care for more than 1500 patients. Our unit has been accredited, according to the quality standards of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] (GETECCU), as a comprehensive care unit for patients with IBD. The professionals who comprise the working group (physicians and nurses) have extensive experience in IBD management.

Brief description of the IBD-Control (original, in English): development and validationThe IBD-Control19 is a brief document (one side of a sheet of A4 paper) and a simple one, with five sections. The first four sections contain 13 categorical questions, and the fifth consists of a horizontal visual analogue scale (VAS). The patient is asked about IBD management in the past two weeks. The “IBD-Control-8” is a subscore that is calculated with the sum of the scores for eight questions. It is converted to a 0–16 score (0 = worst management). Both the IBD-Control-8 and the IBD-Control-VAS have the goal of representing a summary measure of the same construct.

Its phases of development and validation were comprehensive and rigorous. Several measurements, including classic indices of IBD activity, generic and specific quality-of-life questionnaires, and the physician's overall assessment were used as a benchmark comparator for the IBD-Control.

Translation into Spanish and validation of the IBD-Control: the EII-ControlA prospective, single-centre study with two phases, translation into Spanish and subsequent prospective validation of the IBD-Control questionnaire: the EII-Control.

Translation of the questionnaire: the EII-ControlThe translation was done by members of our group with expertise in English. After the initial translation, as in the original study, its comprehensibility, content validity and acceptability were determined in a structured manner by a group of 30 patients termed the “pilot group”. After they had read the translated questionnaire, they were asked for their annotations, comments and questions in relation to the content and format thereof; the team of investigators addressed all of them and their changes were implemented by group consensus, producing the final version: the EII-Control.

Prospective validation phase of the EII-Control questionnaireThe patients included were assessed in two successive visits: the initial visit and the second visit, made either as a scheduled follow-up visit or out of necessity due to IBD reactivation within the study period, which extended from 1 March 2016 to 30 September 2016. In both visits, the EII-Control, other questionnaires and activity indices were administered and also other variables were collected, as specified below.

Study populationConsecutive patients seen in the specialised clinic, diagnosed with IBD (CD, UC or indeterminate colitis), according to the usual criteria (Lennard-Jones), over 18 years of age who agreed to take part in the study after receiving a detailed explanation thereof and signing the informed consent form. We excluded people who had cognitive decline or were unable to understand or fill in the questionnaires. Important data about the patients' IBD (location, extension, phenotype, presence or absence of perianal disease, duration, number of prior hospitalisations and surgeries, presence or absence of stomas, current treatment, comorbidities and tobacco use) were also available and were collected.

Evaluations performed in visitsThe evaluations needed to validate the test were obtained in each visit (initial and second visit).

- •

Questionnaires: the patients self-administered the following questionnaires using a computerised tool placed to this end in the outpatient waiting room; they were assisted by the research nurse the first time they used it as well as whenever they needed help with it.

- -

EII-Control (questionnaire to be validated, Appendix B Annex I).

- -

IBD-specific quality-of-life questionnaire in Spanish, abridged version: CCVEII-9.

- -

General quality-of-life questionnaire (EuroQol), Spanish version: EQ-5D.24

- -

Hospital Anxiety Scale (HAS) and Hospital Depression Scale (HDS), Spanish version.25

- -

Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS), Spanish version: this questionnaire was added to our study; it was not included in the original study by Bodger et al.19 We decided to include it in view of the importance of this symptom in patients with IBD.

- -

- •

Activity indices and physician's assessment: the physician who cared for the patient calculated the corresponding activity indices (Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index [SCCAI] for UC and Harvey-Bradshaw index for CD) and established an overall clinical assessment (remission, mild, moderate or severe), with blinding to the results of the questionnaires completed by the patient. The treatment the patient was on at that time and all changes in treatment stemming from consultation that led to a change in the patient's situation (start of new treatments, adjustment or suspension of doses of prior drugs or indication for assessment/surgical treatment) were recorded.

- •

Laboratory testing, biomarkers and other examinations/diagnostic tests: all patients had, in both visits, recent laboratory results (within the month before the visit), including biomarkers and other important determinations.

Psychometric properties evaluate reliability (the accuracy of the measurement scale, i.e., determination of the minimum error in measurement) and validity (the capacity of the instrument to measure the characteristics that it sets out to measure) of the EII-Control. Reliability includes internal consistency (homogeneity of items comprising a scale; given that they intend to measure a single concept, it is to be expected that responses to them will be inter-related) and reproducibility/repeatability of measurements (degree to which the measure provides identical or similar results when used repeatedly in the same individuals when their health condition has not changed). Validity includes construct validity (analysing whether the questionnaire is related to the desired measurement) and response capacity (detection of significant changes over time), determining the cut-off points that distinguish quiescent from active disease. The statistical details of these measurements shall now be reviewed.

Internal consistency was evaluated for the categorical variables and subscales (EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA [(escala visual analógica) Spanish initialism for visual analogue scale (VAS)], with Cronbach's α coefficient26 and with the correlation measured with Spearman's coefficient for each question with the EII-Control-EVA and with the general value of the CCVEII-9.

Reproducibility/repeatability was evaluated with the intraclass correlation coefficient firstly in all patients who completed the two assessments in the initial and second visit, and secondly only with patients with stable disease in the second visit, controlled by equal values on Question 2 of the EII-Control (answer “sin cambios” [no change]) and variation by at least 10 points on the CCVEII-9.

Construct validity was evaluated by means of analysis of correlation and regression through comparison of scores derived from the questionnaire, with external measures independent of the patient's state of health. These measures included the following questionnaires: the EQ-5D, CCVEII-9, HAS and HDS, and FSS; clinical activity indices; and the physician's overall assessment. High correlation coefficient values and suitable adjustment to validated questionnaires indicate suitable validity. Positive correlations with QoL indicators indicate suitable validity of the questionnaire to be evaluated, like negative correlations with elements related to health or disease severity, such as indicators of anxiety, depression and severity. The relationship between the EII-Control and its subscales with medical assessment were compared to the analysis of variance test. Bivariate correlations were expressed in terms of Spearman's correlation coefficients and mean scores between groups were compared with Student's t-test or analysis of variance. Multivariate linear regression was used to examine the relative strength and independence of the individual questions as predictors of the various external measures of health status and to select the items to be included in the subscores.

The validity of the EII-Control-8 subscale was also analysed through the relationship of the values of the EII-Control-8 questionnaire grouped two by two with the values of the score on the EQ-5D questionnaire.

To analyse response capacity or response prediction capacity, patients who had presented a reduction in their QoL measured on the CCVEII-9 questionnaire — that is to say, patients with a lower score on this questionnaire in the second visit than in the initial visit — were selected. This was calculated using the mean difference for the EII-Control, EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA in three groups of patients identified by having a variation lower than 10, equal to 10 or greater than 10 on the CCVEII-9 questionnaire on the second visit compared to the initial visit. Effect size was calculated in both questionnaires and compared.

To determine cut-off points to detect a “quiescent state”, patients were considered to be in such a state if they met these four conditions:

- •

Medical criteria for inactive disease (“remission” in the physician's overall assessment).

- •

Not receiving oral treatment at that time with corticosteroids, induction with biologics, antibiotics for IBD; being on a waiting list for surgical treatment; or requiring treatment escalation as a result of the visit.

- •

SCCAI < 4 or Harvey-Bradshaw index ≤4 and total score for CCVEII 9 < 90.

- •

Response of 0 or 2 to Question 2 of the EII-Control questionnaire (indicates that the disease has not changed or has improved in the past 2 weeks — i.e., excludes patients who answer that their intestinal symptoms are “worse”).

The subjects who met the four criteria above were considered well managed or “quiescent”, and those who did not were considered “not quiescent”. Analysis of diagnostic efficacy was used to evaluate EII-Control performance as a tool to identify quiescent patients. Given the anticipated clinical application, we established some optimal cut-off scores, centring our efforts on achieving high specificity (≥85%) to minimise the risk of false positives (identifying a non-quiescent patient as quiescent). The cut-off value with the highest sensitivity × specificity product was selected, as described.

Calculation of sample size and statistical analysisThe original study was conducted with 300 patients in an area with a population similar to our centre (350,000–400,000 people). The sample size calculated, with a 5% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval, assuming 50% sample heterogeneity, was 250–300, similar to that of the original study.

The descriptive study included calculations of mean, median, standard deviation, minimum and maximum for the quantitative variables and absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables. The psychometric study was done with the methodology indicated in each specific section.

The data obtained were collected in an Excel® database and subsequently analysed with the SPSS® software program, licence for use from the Universidad de Zaragoza [University of Zaragoza], with a 95% confidence interval, equivalent to a type i error of 5%.

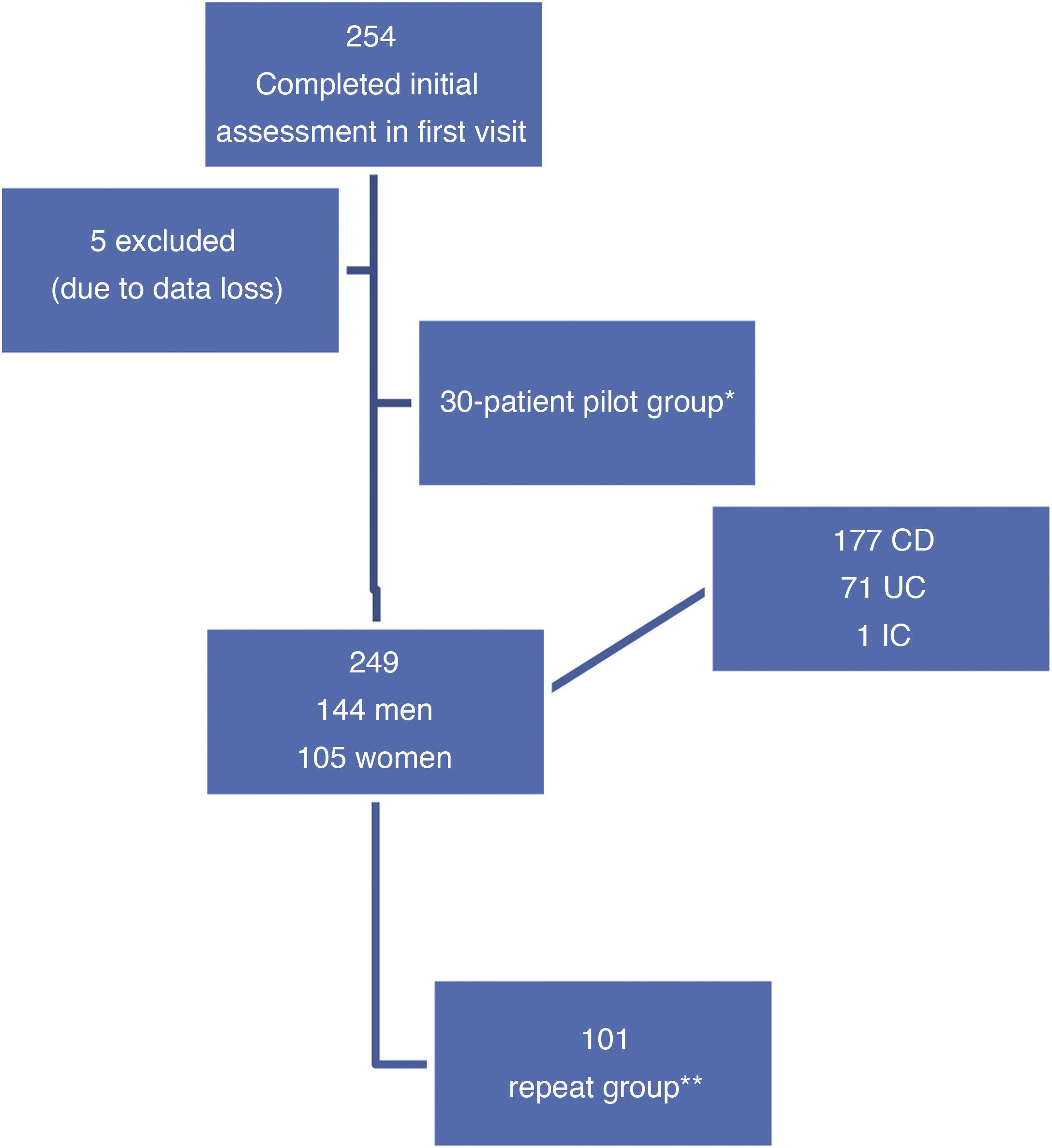

ResultsIn the initial visit, 254 consecutive patients were included; five were excluded due to data loss during processing (first visit n = 249 patients). Thirty patients formed the pilot group to assess the comprehensibility of the questionnaire once it had been translated. The second visit was made by 101 patients (repeat group) (Fig. 1).

Patient flow chart. CD: Crohn's disease; IC: indeterminate colitis; UC: ulcerative colitis.

*Patients who read the questionnaire after it was translated to assess its comprehensibility, content validity and acceptability, before the definitive version.

**Patients who repeated the entire assessment in two successive visits (initial visit and second visit) according to clinical practice.

The pilot group that read the first version of the questionnaire once it had been translated to Spanish consisted of 30 patients (17 women and 13 men): 14 with UC, 13 with CD and one with indeterminate colitis, between 18 and 65 years of age. After jointly reviewing it with the physicians and nurses on the unit, and establishing its suitable comprehensibility and acceptability on the part of the patients, the final version of the EII-Control was generated.

Prospective validation phasePatient dataA total of 249 patients were included in the baseline visit; their characteristics appear in Table 1. Some 86% of the patients were of Spanish nationality. From the cohort of patients evaluated at the baseline visit, 101 were reassessed in their second follow-up visit (their characteristics are shown in Table 1).

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristics | All patients from the baseline visit (n = 249) | Patients from the second visit (repeat group) (n = 101) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 46 | 43 |

| Type of disease, n (%) | ||

| CD | 177 (71.08) | 71 (73.2) |

| UC | 71 (28.5) | 26 (26.8) |

| IC | 1 (0.4) | 0 |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 144 (57.8) | 53 (54.6) |

| Female | 105 (42.2) | 44 (45.4) |

| Prior surgery, n (%) | ||

| Abdominal surgery | 41 (16.3) | 19 (19.6) |

| Perianal surgery | 19 (7.6) | 6 (6.2) |

| No | 181 (72.6) | 69 (71.1) |

| Perianal disease, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 40 (16.1) | 17 (17.5) |

| No | 209 (83.9) | 80 (82.5) |

| Stoma, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 3 (1.2) | 1 (1.04) |

| No | 246 (98.8) | 96 (98.96) |

| Tobacco use, n (%) | ||

| Non-smokers | 77 (33.6) | 32 (33) |

| Former smokers | 106 (46.2) | 36 (37) |

| Smokers | 46 (20.1) | 18 (18.5) |

| Unknown | 20 | 11 (11.5) |

| Treatments, n (%) | ||

| No treatment | 27 (11.5) | 10 (2.06) |

| 5-ASA | 71 (28.5) | 28 (28.86) |

| Oral corticosteroids | 3 | 0 |

| Immunosuppressants | 118 (50.0) | 50 (51.54) |

| Biologics | 90 (37.2) | 46 (47.42) |

| Physician's overall assessment, n (%) | ||

| Inactive | 101 (44.9) | 31 (31.9) |

| Mild | 80 (35.5) | 37 (38.1) |

| Moderate | 34 (15.1) | 20 (20.6) |

| Severe | 10 (4.4) | 5 (5.15) |

| Extraintestinal signs, n (%) | 63 (26.8) | 24 (23.7) |

| Quality-of-life questionnaires, mean ± SD | ||

| EQ-5D | 0.80 ± 0.19 | 0.82 ± 0.19 |

| EQ-5D-EVA | 69.6 ± 21.2 | 72.9 ± 20.8 |

| CCVEII-9 | 45.1 ± 10.3 | 46.5 ± 10.7 |

CCVEII-9: IBD-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, abridged version; CD: Crohn's disease; EQ-5D: general quality-of-life questionnaire, Spanish version; IC: indeterminate colitis; SD: standard deviation; UC: ulcerative colitis; EVA: [escala visual analógica] visual analogue scale (VAS).

The correlation of the different individual categorical questions on the EII-Control questionnaire with the value on the EII-Control-EVA subscale, as well as with the general value on the CCVEII-9 questionnaire, were analysed using Spearman's coefficient. All the correlations of the questions were statistically significant in comparison to both values, indicating consistency for the questions on the EII-Control.

The degree of agreement of the 13 categorical questions through Cronbach's α test calculated in the first and second administration of the questionnaire yielded values of 0.833 and 0.801, respectively. In addition, the value of the coefficient was calculated for each question on the questionnaire, assuming that this question was eliminated, yielding very similar values between them and the overall value. All this provides information on the suitable internal consistency of the questionnaire for the construct “disease control”. In addition to this, the subscore of the EII-Control-8 and the score on the EII-control-EVA showed a strong correlation to one another. This was confirmed in patients with IBD of any kind (r = 0.502; P = .047), and with CD (r = 0.546; P < .001) and UC (r = 0.583; P < .001) separately.

ReproducibilityIn the group of all the patients who completed the assessments in the initial visit and second visit (n = 101), no significant differences were detected in mean scores on the EII-Control or EII-control-EVA between the visits, and a slight variation was detected on the EII-Control-8; this was not the case in the group of patients whose disease status did not change (stable disease, n = 40). Intraclass correlation coefficients were high in both groups of patients; in this regard, the EII-Control had higher values than the EII-Control-EVA and the EII-Control-8 (Table 2).

Reproducibility of the total and summary scores on the EII-Control for the repeat group and for stable patients (intraclass correlation coefficient and mean difference).

| ICC (95% CI) | Mean ± SD, first visit | Mean ± SD, follow-up visit | Mean difference (95% CI) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total patients, n = 101 | |||||

| EII-Control | 0.703 (0.560−0.800) | 16.04 ± 6.33 | 16.62 ± 5.95 | −1.079 (−2.202; 0.043) | .059 |

| EII-Control-EVA | 0.613 (0.426−0.739) | 75.16 ± 22.88 | 77.66 ± 19.087 | −3.069 (−7.281; 1.143) | .151 |

| EII-Control-8 | 0.580 (0.434−0.696) | 10.35 ± 4.06 | 11.36 ± 4.04 | −1.000 (−1.743; 0.276) | .007 |

| Patients with stable disease, n = 40 | |||||

| EII-Control | 0.862 (0.586−0.864) | 17.10 ± 5.33 | 18.10 ± 5.27 | −2.18; 0.181 | .095 |

| EII-Control-EVA | 0.526 (0.412−0.835) | 76.95 ± 20.50 | 80.60 ± 17.57 | −9.599; 2.299 | .222 |

| EII-Control-8 | 0.580 (0.434−0.696) | 11.55 ± 3.69 | 12.10 ± 3.31 | −0.55 (−1.316; 0.216) | .155 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; ICC: intraclass correlation coefficient; SD: standard deviation; EVA: [escala visual analógica] visual analogue scale (VAS).

The results of the analyses of correlation of the EII-Control and the variables for comparison are presented in Table 3 in the group of 249 patients who took the test at least once. The correlation was significant in all cases for the EII-Control, EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA. It was positive with all QoL scales and with medical assessment and was negative with those of symptoms. This indicates suitable validity for the EII-Control, since the value thereof varied in the same direction as the CCVEII-9, the EQ-5D and clinical assessment — that is to say, when the values for the CCVEII-9 or the EQ-5D increased or there was a better clinical assessment, the value for the EII-Control also increased, and vice versa. By contrast, correlation with the HAS, HDS and FSS questionnaires and with the SCCAI for UC/Harvey-Bradshaw index was negative, meaning that, with negative evaluation of disease, anxiety, depression and fatigue, the EII-Control value decreased, and vice versa. Question 2, which deals with the presence of feelings of anxiety and depression, showed a statistically significant correlation to the HAS questionnaire (r = −0.136, P = .031), but not to the HDS questionnaire (r = 0.072, P = .258).

Construct validity: correlations between the EII-Control and its summary scores and external measures of health status of patients in the initial evaluation.

| Coefficient (p) | CCVEII-9 | Clinical evaluationa | EQ-5D value | EQ-5D-EVA | HAS | HDS | FSS | SCCAI | Harvey-Bradshaw |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EII-Control | 0.774 (P < .001) | 0.528 (P < .001) | 0.614 (P < .001) | 0.639 (P < .001) | −0.600 (P < .001) | −0.225 (P < .001) | −0.477 (P < .001) | −0.368 (P < .004) | −0.524 (P < .001) |

| EII-Control-8 | 0.812 (P < .001) | 0.557 (P < .001) | 0.812 (P < .001) | 0.676 (P < .001) | 0.672 (P < .001) | 0.255 (P < .001) | −0.497 (P < .001) | −0.485 (P < .001) | −0.574 (P < .001 |

| EII-Control-EVA | 0.558 (P < .001) | 0.416 (P < .001) | 0.664 (P < .001) | 0.639 (P < .001) | −0.399 (P < .001) | −0.218 (P < .001) | −0.245 (P < .001) | −0.385 (P < .002) | 0.371 (P < .001) |

CCVEII-9: IBD-specific quality-of-life questionnaire, abridged version; EQ-5D: general quality-of-life questionnaire, Spanish version; FSS: Fatigue Severity Scale; HAS: Hospital Anxiety Scale; HDS: Hospital Depression Scale; SCCAI: Simple Clinical Colitis Activity Index.

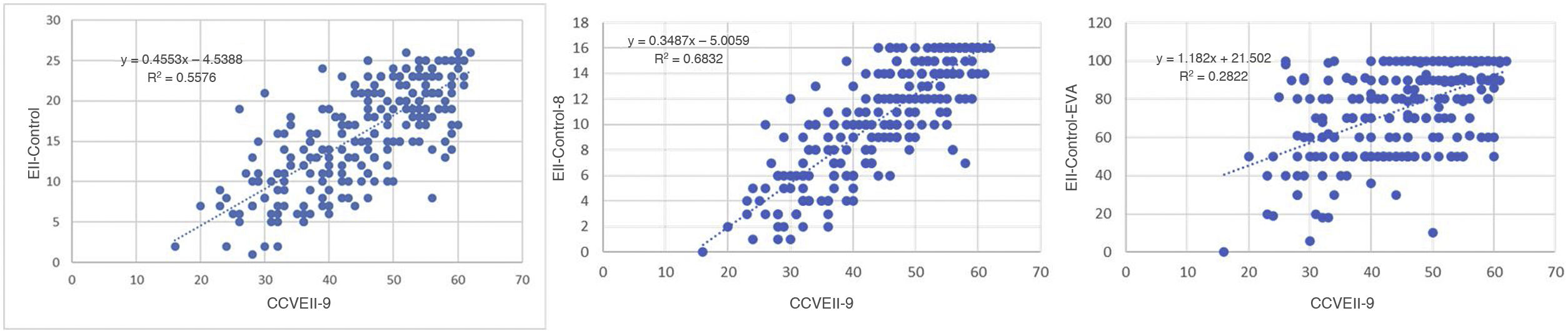

Fig. 2 shows the results for regression on the questionnaires with significant correlation. This figure reveals that the greater correlation between the EII-Control and the CCVEII-9 translated to a better fit for the regression model with an R2 value of 0.5985, indicating a strong relationship between the two questionnaires and that the variability of the CCVEII-9 could predict nearly 60% of the variability of the EII-Control.

With respect to the relationship between the EII-Control and the physician's overall assessment, the values were compared to the analysis of variance test. The results always indicated that the better the patient's condition, the higher the values of the score on the EII-Control and its two subscales (higher score in patients with inactive disease and lower score in patients with severe disease); statistically significant differences were found between groups (P < .001 in all cases).

With respect to the validity of the EII-Control-8 (subscale with questions 1a, 1b, 3a, 3b, 3c, 3d, 3e and 3f), to analyse its capacity to detect health status, the values on the EII-Control-8 questionnaire were related grouped two by two to the values of the score on the EQ-5D. The highest values on the EII-Control-8 showed a growing relationship to the values on the EQ-5D, thus validating the questionnaire.

In addition to that, the correlations between the EII-Control-8 and the CCVEII-9, EII-Control-EVA and EQ-5D were always positive and statistically significant: 0.851 (P < .001), 0.560 (P < .001) and 0.696 (P < .001), respectively; this came to also demonstrate the validity of this measure.

Response capacityThe response capacity of the EII-Control was comparable to that of the CCVEII-9, since both showed statistically significant differences in the two measurements with a higher average in the first assessment (P < .001 in both cases). In the same way, the effect size was limited in both cases and coherent between the two questionnaires: 0.14 on the CCVEII-9 and 0.09 on the EII-Control.

Furthermore, the EII-Control, EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA showed different values in three groups of patients defined by having variation less than 10, equal to 10 or greater than 10 on the CCVEII-9 questionnaire. The effect sizes were moderate (>0.3) or high (>0.7) in the three cases.

Sensitivity and specificity of the EII-Control in the identification of “quiescent” or inactive patientsOf the 249 patients included in the study, 220 were identified as in a quiescent state, according to the criteria selected, in the initial visit.

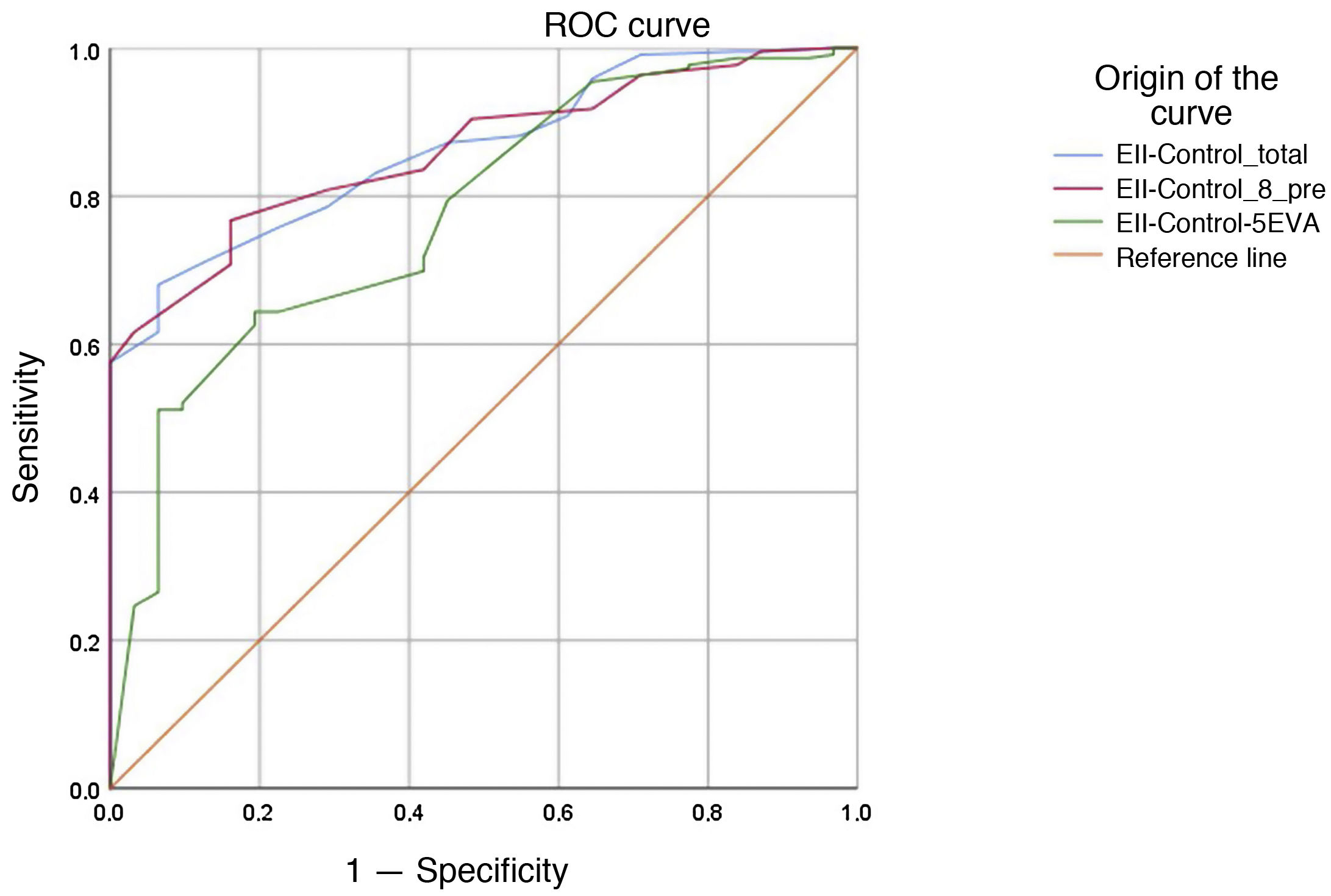

The results for the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the EII-Control, EII-Control-8 and EII-Control-EVA questionnaires are presented in Fig. 3. The values for the area under the curve were 0.864 (95% CI 0.811−0.916) for the EII-Control, 0.862 (95% CI 0.810−0.914) for the EII-Control-8 and 0.776 (95% CI 0.692−0.860) for the EII-Control-EVA (P < .001 in all cases). That is to say, all the scales have the capacity to detect a quiescent state, although the EII-Control-EVA had less credibility. The cut-off points that achieved the best values for sensitivity and specificity were 14 (sensitivity 0.696 and specificity 0.903) for the EII-Control; 11 (sensitivity 0.662 and specificity 0.903) for the EII-Control-8 and 82 (sensitivity 0.516 and specificity 0.903) for the EII-Control-EVA.

These cut-off points would mean that just one out of every 10 patients not meeting our strict clinical criteria for active IBD would be falsely classified as inactive, but none of these “false positives” required any change in treatment at the time of consultation, and all were considered to be cases that were in remission or only mildly active by the treating physician. These data confirmed the possible clinical application of the EII-Control as a tool for quick classification to determine low-risk (inactive) patients suited to alternative forms of follow-up.

The question of whether the presence of Question 2 on quiescent state would influence predictive capacity on the EII-Control questionnaire, which also includes it, was analysed as well. The area under the curve was the same when this question on quiescent state was removed, i.e., 0.731 (95% CI 0.660−0.802).

DiscussionThe IBD-Control questionnaire was designed by Bodger et al. with the aim of offering a quick, easy-to-use assessment of disease control from the patient's perspective. It was developed with patient participation to establish the measurement construct (i.e., what is disease control?) and to create patient-centred items. The predetermined key requirements were that the IBD-Control be applicable to routine clinical care and that it include items related to the two main forms of IBD (CD and UC). The domains identified through discussion with patients on disease control and those published in the literature on QoL in IBD10,27,28 had a considerable consensus; therefore, good control from the patient's perspective means the disease having no repercussions for the main spheres of the patient's life (energy/vitality, ability to carry out day-to-day tasks, sleep, mood and absence of pain and discomfort). A notable aspect of the IBD-Control is its emphasis on patient involvement in creating items and designing the questionnaire, which supplemented the literature review and expert clinical opinion.

The study found that the IBD-Control enjoyed very good acceptance by patients, given the ease of filling it in and the high rates of completion; these characteristics are essential when it is intended to be used in clinical practice. In addition, it demonstrated its powerful measurement properties (psychometric range), which complied with current international standards20–22 and were very solid when they were compared to a wide array of external measures and validation was not limited to showing correlations with traditional disease measures in the patient population, but considered the performance of summary scores on an individual level and for a specific clinical purpose.

Logically, the study has some limitations, despite the rigorous development and validation process. Thus, the authors admit some limitations, especially the possibility of selection bias that is inevitable and inherent to selecting patients willing to complete multiple questionnaires for a validation study. However, since the sample size was large and included subjects with a broad spectrum of demographic and clinical characteristics similar to the local IBD population,23 this possible bias was minimised. In our case, patients were included consecutively without any selection, as long as they met the inclusion criteria and signed the informed consent form; therefore, the selection bias mentioned by the authors was minimal or nonexistent. However, as the authors stated in their discussion, further validation in other settings and in specific subgroups of patients would be desirable. Similarly, different groups of patients in terms of language and culture require such validation.

With this objective, to validate the IBD-Control in Spanish patients, with its more than likely usefulness for our practice, we designed this study. It is important to remember that Spanish is the second most spoken language in the world, underlining the importance of this validation. The validation was based on the IBD-Control questionnaire, which was translated into Spanish in a structured process, yielding the EII-Control. Subsequently, the psychometric prospective validation of the EII-Control was performed as in the original study, with only minimal changes to improve it (for example, including the FSS). Our results were highly consistent with those of Bodger et al., with both validity and reliability having highly overlapping figures, indicating that the translated questionnaire termed the EII-Control is also valid in patients in our setting. On this point, while we do not know, the complexity of the patients in the original study and ours may have been different, as the patients in the original study were population-based, whereas our specialised practice sees the most complicated patients in the area. Even so, the results of the test were not affected, which would support the general validity of the EII-Control in IBD overall. Another difference between in our study and the original study was that we added evaluation of the relationship between the EII-Control score and the FSS. As is known, one of the most common symptoms, even in patients considered in remission, is asthenia or fatigue, which sometimes significantly limits patient QoL. The correlation that we observed between the EII-Control and the FSS scale was very high, supporting the validity of the EII-Control. A matter of interest to both the creators of the original IBD-Control and us was that the tool reliably identified patients in a "quiescent" state, strictly defined with a set of criteria. This was interesting given its potential application in care models that seek to reduce the need for face-to-face consultations in favour of virtual or remote clinical consultations. While this approach to control and monitoring has been gaining importance in recent years, at present, in the “COVID era”, it is even more important and timely. In many cases, telemedicine has become not an objective to be promoted and fulfilled, but a necessity. Our instrument, the EII-Control, achieved practically the same specificity as the original for this purpose; therefore, this property of reliably detecting quiescent patients renders it an ideal tool to achieve this end.

Recently, quality-improvement programmes in IBD in various healthcare environments have highlighted the potential of routine measurement of PROs to help improve patient-centred services.29,30 In this context, given that the current guidelines for IBD do not endorse or recommend the use of any specific PRO instrument in monitoring care, such that they remain research tools more than anything, we believe that the simplicity of the EII-Control together with its robust measurement properties make it very suitable for this use, in addition to its role in clinical studies. The instrument also offers the possibility of capturing serial data on patient-perceived outcomes while placing a minimal burden on the user, and its content and abridged format make it especially well suited to adaptation to electronic capture through web systems and mobile applications.

Conflicts of interestRVL has received scientific advice, research support and/or training activities from AbbVie, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and Takeda. SGL has received support for attending scientific meetings from AbbVie, MSD, FAES-FARMA, Ferring, Shire, Takeda, Pfizer and Janssen. SGL has also received fees for consulting or research support from AbbVie, Janssen, MSD and Takeda.

FGG has received scientific advice, research support and/or training activities from AbbVie, Janssen, MSD, Pfizer and Takeda.

All other authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.