Colonoscopy is the gold standard for the detection and prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC). However, some individuals are diagnosed with CRC soon after a previous colonoscopy.

AimsTo evaluate the rate of new onset or missed CRC after a previous colonoscopy and to study potential risk factors.

MethodsPatients in our endoscopy database diagnosed with CRC from March 2004 to September 2011 were identified, selecting those with a colonoscopy performed within the previous 5 years. Medical records included age, gender, comorbidities and colonoscopy indication. Tumour characteristics studied were localisation, size, histological grade and TNM stage and possible cause. These patients were compared with those diagnosed with CRC at their first endoscopy (sporadic CRC-control group).

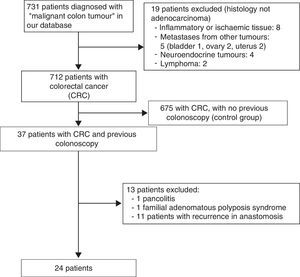

ResultsA total of 712 patients with CRC were included; 24 patients (3.6%) had undergone colonoscopy within the previous 5 years (50% male, 50% female, mean age 72). Post-colonoscopy CRCs were attributed to: 1 (4.2%) incomplete colonoscopy, 4 (16.6%) incomplete polyp removal, 1 (4.2%) failed biopsy, 8 (33.3%) ‘missed lesions’ and 10 (41.7%) new onset CRC. Post-colonoscopy CRCs were smaller in size than sporadic CRCs (3.2cm vs. 4.5cm, p<0.001) and were mainly located in the proximal colon (63% vs. 35%, p=0.006); no difference in histological grade was found (p=0.125), although there was a tendency towards a lower TNM stage (p=0.053).

ConclusionsThere is a minor risk of CRC development after a previous colonoscopy (3.6%). Most of these (58.4%) are due to preventable factors. Post-colonoscopy CRCs were smaller and mainly right-sided, with a tendency towards an earlier TNM stage.

La colonoscopia es el gold standard en la detección y prevención del cáncer colorrectal (CCR). No obstante, en la práctica clínica habitual nos encontramos con pacientes que desarrollan un CCR a pesar de que se habían sometido a una colonoscopia previamente.

ObjetivosEstudiar la prevalencia de CCR de novo o no detectados tras la realización de una colonoscopia y valorar los posibles factores de riesgo.

PacientesSe incluyen los pacientes diagnosticados de CCR registrados en la base de datos endoscópicos de nuestro hospital entre marzo de 2004 y septiembre de 2011. Identificamos los pacientes que tenían realizada una colonoscopia en los 5 años previos. Se recogieron: edad, sexo, comorbilidades e indicación de la colonoscopia, tamaño y localización del tumor, así como su grado de diferenciación, su clasificación TNM y las posibles causas. Posteriormente comparamos este subgrupo de pacientes con los que habían sido diagnosticados de CCR en su primera colonoscopia (CCR esporádico, grupo control).

ResultadosSe incluyeron 712 pacientes diagnosticados de CCR. Veinticuatro de ellos (3,6%) tenían una colonoscopia realizada en los 5 años previos (50% varones, 50% mujeres, edad media 72 años). Estos CCR poscolonoscopia se atribuyeron: uno (4,2%) a colonoscopia incompleta, 4 (16,6%) a resección incompleta de adenoma, uno (4,2%) a biopsia fallida, 8 (33,3%) a «lesiones no detectadas» y 10 (41,7%) fueron CCR de nueva aparición. Los CCR poscolonoscopia eran de menor tamaño que los CCR esporádicos (3,2 vs 4,5cm, p<0,001), principalmente localizados en colon proximal (62% vs 35%, p=0,006); no hubo diferencias en cuanto al grado histológico (p=0,125), pero sí una tendencia a presentar un mejor estadio TNM (p=0,053).

ConclusionesLa tasa de CCR tras una colonoscopia previa en nuestra serie es del 3,6%. Las posibles causas de estos CCR se atribuyeron en su mayoría (58,4%) a factores relacionados al procedimiento endoscópico y, por tanto, evitables. Estos hallazgos reafirman la importancia de ajustarse a los indicadores de calidad de la colonoscopia. Los CCR poscolonoscopia fueron de menor tamaño, localizados fundamentalmente en colon derecho y con tendencia a presentar un estadio TNM más precoz.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of death in developed countries.1,2 Approximately half of the 22000 cases detected annually in Spain are fatal.3 Prognosis depends on early detection4 and, especially, endoscopic removal of precursor adenomatous polyps,5 as shown in US (The National Polyp Study)5 and European (The Italian Multicenter Study) studies.6 Colonoscopy is, in theory, the best diagnostic tool for the early detection of CRC and for removal of adenomatous precursor lesions.7 However, this technique is not always infallible, even in expert hands, and the development of CRC has occasionally been described in patients in whom this endoscopic examination had previously been performed.8,9 Thus, in the Polyp Prevention Trial Continued Follow-Up Study conducted in the US, the authors found 9 patients who developed CRC despite periodic endoscopic surveillance.10 It is therefore necessary to determine the causes and nature of these post-colonoscopy CRCs in order to improve prevention. Post-colonoscopy CRC can occur for 2 reasons: (a) factors inherent to the endoscopic procedure itself, such as incomplete or inadequate endoscopic examination, or incomplete removal of precursor adenomas, or (b) biological factors inherent to the CRC which make it more aggressive and speed up development and progression.

The risk of post-colonoscopy CRC, either due to rapid development or failure to detect and remove precursor polyps, is not fully understood. However, identifying and improving the modifiable factors, such as the detection and resection of precursor lesions, could reduce the risk of developing post-colonoscopy CRC. The aim of this study was to evaluate the rate of post-colonoscopy CRC (previously undetected or new onset) in our population and the associated risk factors.

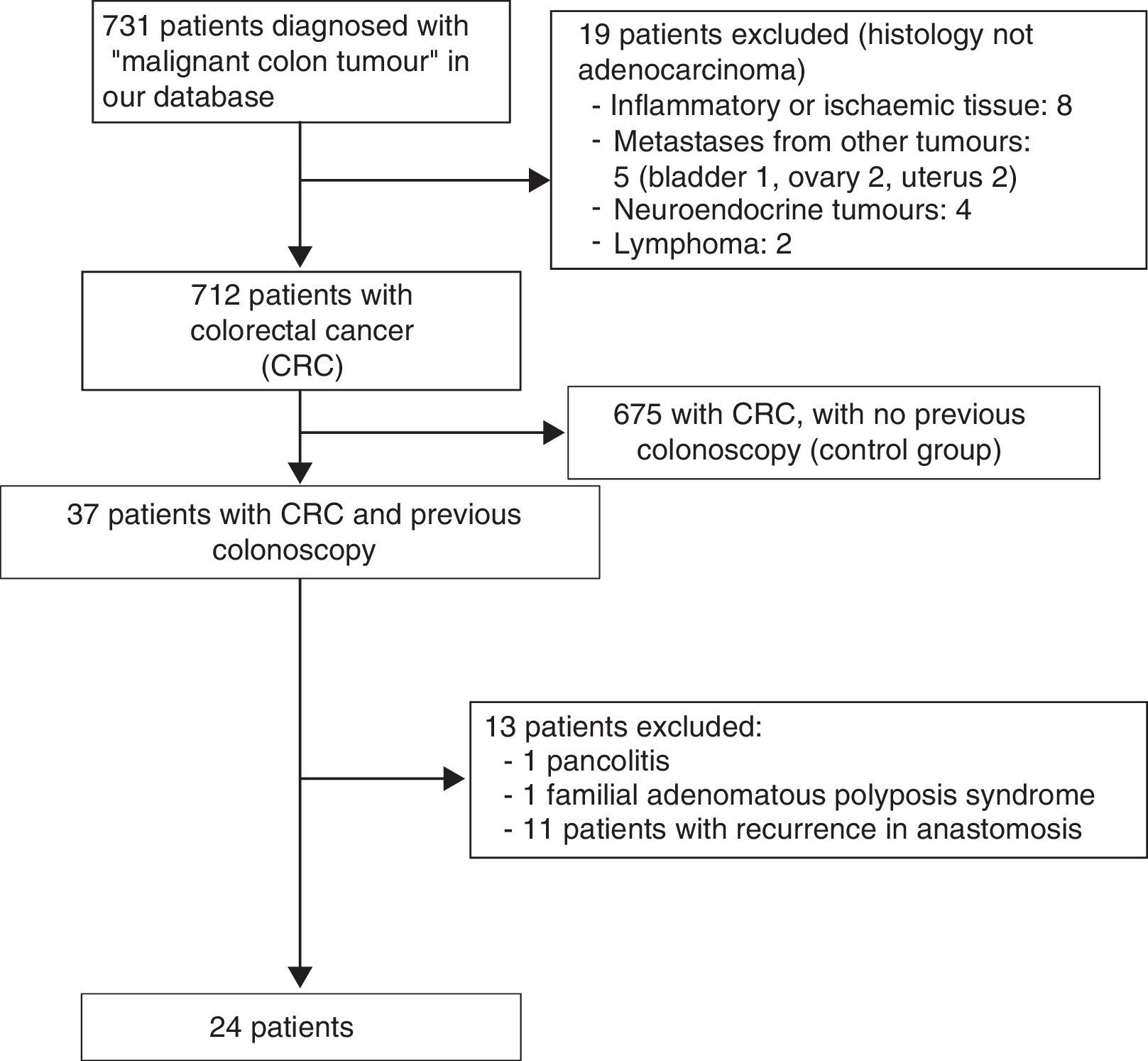

Patients and methodsThis was a retrospective case-control study conducted in the gastroenterology department of Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid (Spain) between March 2004 and September 2011. Patients diagnosed with a “malignant colon tumour” were identified in the electronic database of the Endoscopy Unit (Endobase, Olympus). Patients who had undergone a colonoscopy in the previous 5 years were then selected (this first colonoscopy was called the “index colonoscopy”). A period of 5 years was chosen because the risk of developing CRC or advanced adenoma within this period is very low, a trend that has also been evidenced in cost-effectiveness studies of CRC screening strategies, which recommended that screening colonoscopies be performed at intervals of at least 5 years.11

Patients who presented anastomotic recurrence of previous CRCs, those with familial polyposis or inflammatory bowel disease, and patients whose index colonoscopy was performed in another hospital and diagnosed in our centre, were excluded.

Patients with sporadic CRC were included as a control group, i.e. patients diagnosed in the first recorded colonoscopy in our database during the same period.

Our gastroenterology department belongs to the Hospital Clínico Universitario and serves a population of 250000 inhabitants. The colonoscopies were performed by 7 staff endoscopists with extensive experience in these procedures (they perform a mean of 800–1000 colonoscopies annually). Olympus white light endoscopes with video processors from the Evis Exera CV160-CLE145, Evis Exera II CV180 and Evis Exera II CV165 series were used in the study. Patients were given conscious sedation with midazolam and fentanyl by specialised nursing staff, always under the supervision of the endoscopist. Patient demographic data (age, sex, comorbidities), colonoscopy indication (index and diagnostic), quality of the preparation, extension of the examination and findings of the index colonoscopy were recorded.

The colon was divided into 4 segments: caecum-ascending colon, transverse colon, left colon and rectum. The colonoscopy was considered complete if the base of the caecum was reached and there was photographic documentation of that area. The quality of the endoscopic preparation was classified as “good/adequate” or “poor/inadequate” according to the endoscopist's impression. The tumour location was estimated using anatomical references and the distance on withdrawal. The following tumour parameters were recorded: location, size, histological grade and TNM stage. The World Health Organization classification was used for the TNM grade.12 Polyps were classified as hyperplastic and adenomatous. Advanced adenoma was defined as an adenomatous polyp of more than 10mm in size and/or with a villous component and/or high grade dysplasia. The algorithm drawn up by Pabby et al.13 was used to explain the most likely aetiology of the post-colonoscopy CRC. These authors described 4 possible aetiologies: (1) “incomplete removal” for tumours arising in the same anatomic segment where an adenomatous polyp had previously been removed; (2) “failed biopsy detection”, which included lesions suspected by the endoscopist to be malignant but with no histopathological confirmation; (3) “missed cancer”, which included CRCs in a location different from the site where an adenoma had previously been removed and diagnosed within 30 months of the index colonoscopy (regardless of size or stage), or diagnosed >30 months after the index colonoscopy with the features of an advanced cancer (stages III–IV); and (4) “new cancer”, which included CRCs detected in an anatomical site different from where an adenoma had previously been removed, detected >30 months after the index colonoscopy and no findings suggesting an advanced tumour.

The study was approved by the hospital clinical research ethics committee.

In the statistical study, quantitative variables are shown as means and qualitative variables as frequency distribution. We analysed the association between qualitative variables using the Chi-squared test. If more than 20% of cells had expected values less than 5, either Fisher's exact test or the likelihood ratio test for variables with more than 2 categories was used. Quantitative variables were compared using the Student t-test for independent samples or the Mann–Whitney test, as applicable. Data were analysed using SPSS version 19.0 for Windows. Values were considered statistically significant when p<0.05.

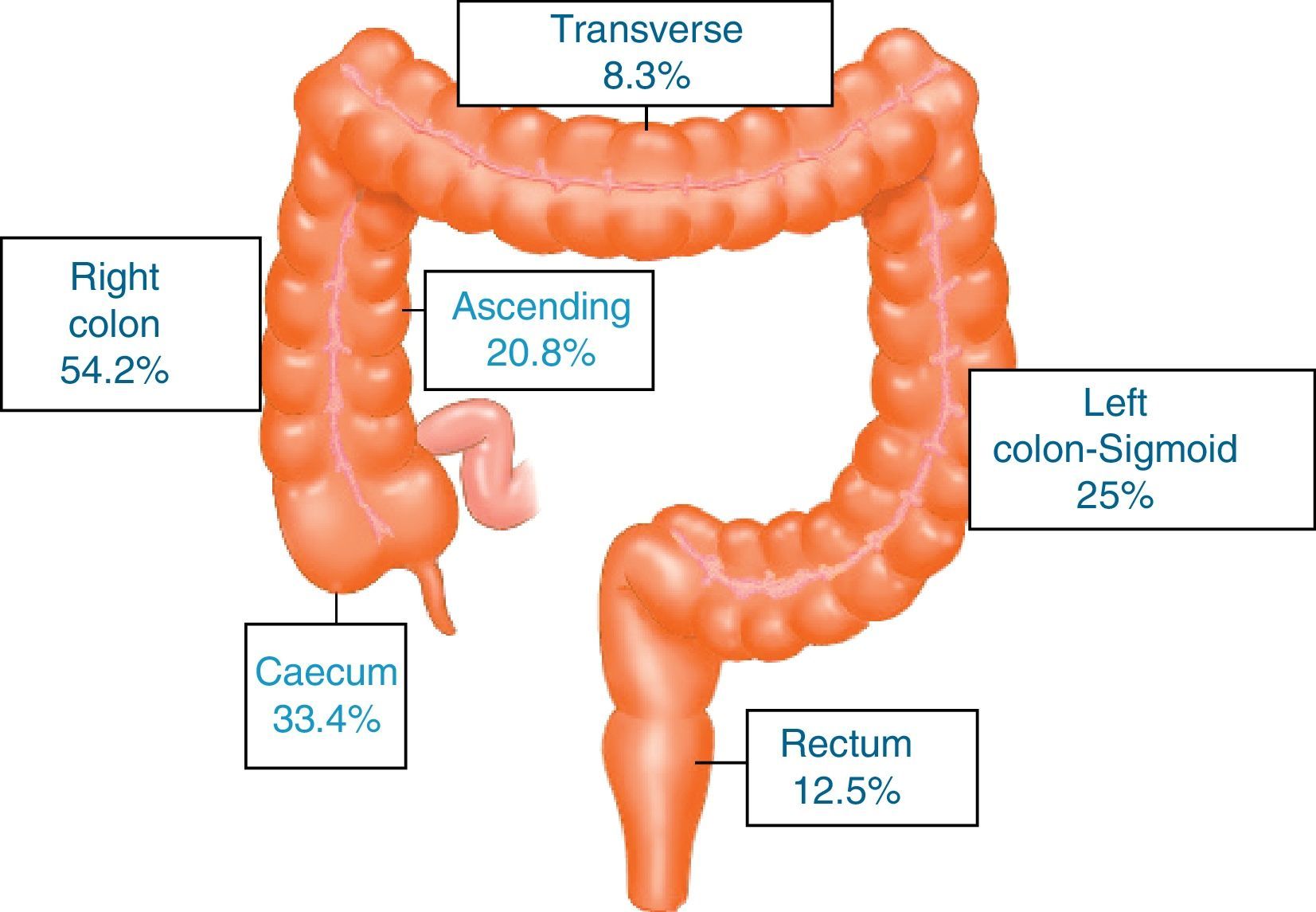

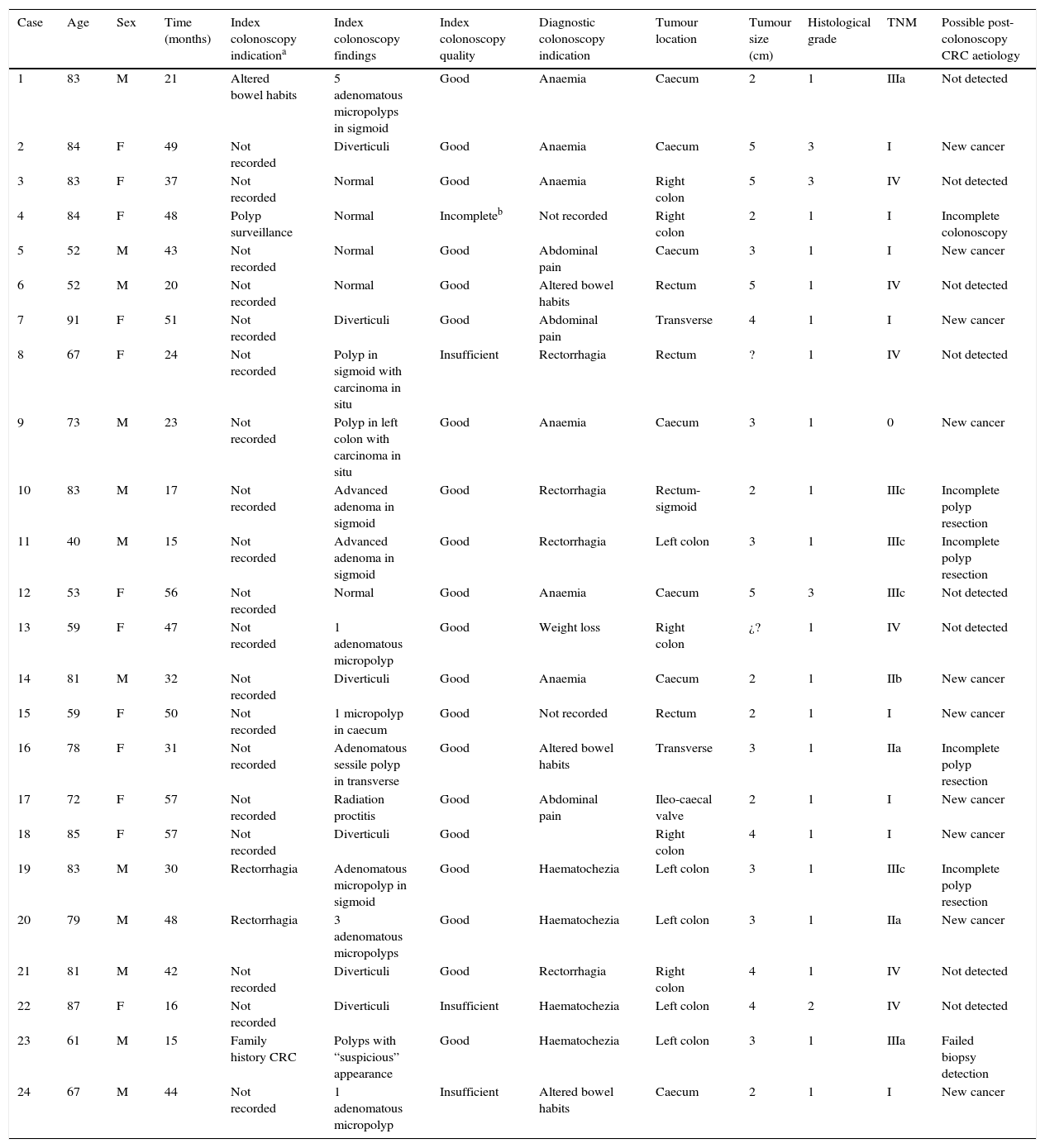

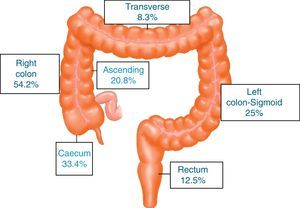

ResultsA total of 731 patients diagnosed with “malignant colon tumour” were identified in our endoscopic database. The patient flow chart is shown in Fig. 1. Twenty-four patients (3.6%) who had undergone colonoscopy in the previous 5 years were eventually included in the study: 12 men and 12 women with mean age 72.4 years (range, 52–91). The mean time between the index colonoscopy and the diagnostic colonoscopy was 34 months (range, 15–57). Demographic data, time between both colonoscopies, indications and findings in both colonoscopies, quality of the index endoscopy and the tumour characteristics are shown in Table 1. According to the Charlson index, 67% of patients had comorbidities, with diabetes (31%) and congestive heart failure (37.5%) being the most common. The main indications for performing the diagnostic colonoscopy were rectal bleeding-haematochezia (30%) and anaemia (22%). Mean tumour size was 3.2cm (95% CI: 2.7–3.6) and more than half were located in the right colon (Fig. 2). The grade of tumour differentiation was good (G1–G2) in most cases (87.5%) and poor (G3) in 3 patients (12.5%). The TNM stage of the tumours was as follows: 1 case of carcinoma in situ (4.2%), 8 tumours presented stage I (33.4%), 3 cases (12.5%) were stage II (2 stage IIa, 1 stage IIb), 6 tumours were found in stage III (25%), and finally, 6 patients presented tumour dissemination (25%).

Demographic data, characteristics of the colonoscopies, post-colonoscopy CRC and its possible causes.

| Case | Age | Sex | Time (months) | Index colonoscopy indicationa | Index colonoscopy findings | Index colonoscopy quality | Diagnostic colonoscopy indication | Tumour location | Tumour size (cm) | Histological grade | TNM | Possible post-colonoscopy CRC aetiology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 83 | M | 21 | Altered bowel habits | 5 adenomatous micropolyps in sigmoid | Good | Anaemia | Caecum | 2 | 1 | IIIa | Not detected |

| 2 | 84 | F | 49 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Good | Anaemia | Caecum | 5 | 3 | I | New cancer |

| 3 | 83 | F | 37 | Not recorded | Normal | Good | Anaemia | Right colon | 5 | 3 | IV | Not detected |

| 4 | 84 | F | 48 | Polyp surveillance | Normal | Incompleteb | Not recorded | Right colon | 2 | 1 | I | Incomplete colonoscopy |

| 5 | 52 | M | 43 | Not recorded | Normal | Good | Abdominal pain | Caecum | 3 | 1 | I | New cancer |

| 6 | 52 | M | 20 | Not recorded | Normal | Good | Altered bowel habits | Rectum | 5 | 1 | IV | Not detected |

| 7 | 91 | F | 51 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Good | Abdominal pain | Transverse | 4 | 1 | I | New cancer |

| 8 | 67 | F | 24 | Not recorded | Polyp in sigmoid with carcinoma in situ | Insufficient | Rectorrhagia | Rectum | ? | 1 | IV | Not detected |

| 9 | 73 | M | 23 | Not recorded | Polyp in left colon with carcinoma in situ | Good | Anaemia | Caecum | 3 | 1 | 0 | New cancer |

| 10 | 83 | M | 17 | Not recorded | Advanced adenoma in sigmoid | Good | Rectorrhagia | Rectum-sigmoid | 2 | 1 | IIIc | Incomplete polyp resection |

| 11 | 40 | M | 15 | Not recorded | Advanced adenoma in sigmoid | Good | Rectorrhagia | Left colon | 3 | 1 | IIIc | Incomplete polyp resection |

| 12 | 53 | F | 56 | Not recorded | Normal | Good | Anaemia | Caecum | 5 | 3 | IIIc | Not detected |

| 13 | 59 | F | 47 | Not recorded | 1 adenomatous micropolyp | Good | Weight loss | Right colon | ¿? | 1 | IV | Not detected |

| 14 | 81 | M | 32 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Good | Anaemia | Caecum | 2 | 1 | IIb | New cancer |

| 15 | 59 | F | 50 | Not recorded | 1 micropolyp in caecum | Good | Not recorded | Rectum | 2 | 1 | I | New cancer |

| 16 | 78 | F | 31 | Not recorded | Adenomatous sessile polyp in transverse | Good | Altered bowel habits | Transverse | 3 | 1 | IIa | Incomplete polyp resection |

| 17 | 72 | F | 57 | Not recorded | Radiation proctitis | Good | Abdominal pain | Ileo-caecal valve | 2 | 1 | I | New cancer |

| 18 | 85 | F | 57 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Good | Right colon | 4 | 1 | I | New cancer | |

| 19 | 83 | M | 30 | Rectorrhagia | Adenomatous micropolyp in sigmoid | Good | Haematochezia | Left colon | 3 | 1 | IIIc | Incomplete polyp resection |

| 20 | 79 | M | 48 | Rectorrhagia | 3 adenomatous micropolyps | Good | Haematochezia | Left colon | 3 | 1 | IIa | New cancer |

| 21 | 81 | M | 42 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Good | Rectorrhagia | Right colon | 4 | 1 | IV | Not detected |

| 22 | 87 | F | 16 | Not recorded | Diverticuli | Insufficient | Haematochezia | Left colon | 4 | 2 | IV | Not detected |

| 23 | 61 | M | 15 | Family history CRC | Polyps with “suspicious” appearance | Good | Haematochezia | Left colon | 3 | 1 | IIIa | Failed biopsy detection |

| 24 | 67 | M | 44 | Not recorded | 1 adenomatous micropolyp | Insufficient | Altered bowel habits | Caecum | 2 | 1 | I | New cancer |

The possible aetiology of these 24 post-colonoscopy CRC were attributed to:

- 1.

Incomplete polyp resection in 4 cases (16.6%).

- 2.

Incomplete colonoscopy in 1 patient (4.2%).

- 3.

Failed biopsy detection in 1 case (4.2%).

- 4.

Eight tumours (33.3%) were considered as “missed CRC”.

- 5.

Finally, 10 tumours were considered as “new CRC” (41.7%).

Although the post-colonoscopy CRC was detected in case 9 within 30 months, we classified it as “new”, despite the Pabby classification, given its very early stage (T0).

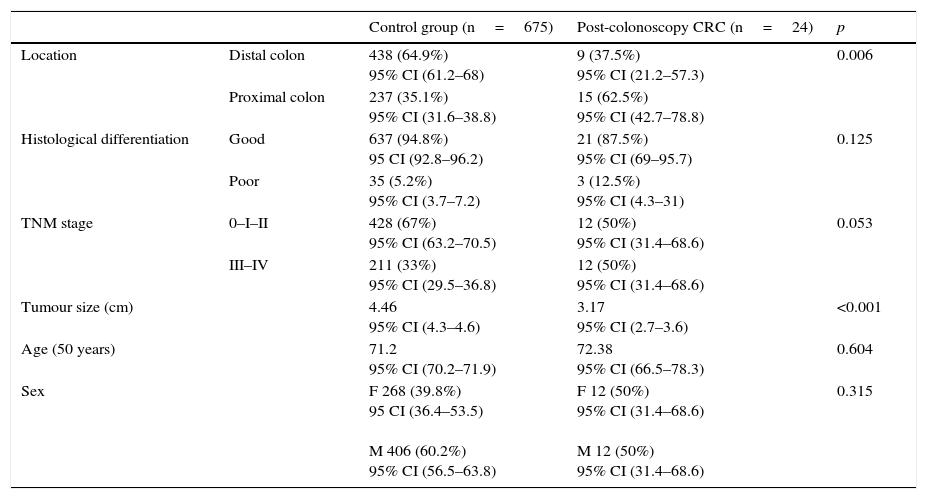

These 24 post-colonoscopy CRCs were compared with the group of tumours diagnosed in the 625 patients in the first colonoscopy (control group). Post-colonoscopy CRCs were smaller (3.17 vs. 4.46, p<0.001), and mainly located in the proximal colon segments (63% vs. 35%, p=0.006). The histological grade was similar, but the post-colonoscopy CRCs had a tendency towards an earlier TNM stage. There were no differences with respect to age and sex in both groups (Table 2).

Patient demographic and tumour characteristics in both groups.

| Control group (n=675) | Post-colonoscopy CRC (n=24) | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Distal colon | 438 (64.9%) 95% CI (61.2–68) | 9 (37.5%) 95% CI (21.2–57.3) | 0.006 |

| Proximal colon | 237 (35.1%) 95% CI (31.6–38.8) | 15 (62.5%) 95% CI (42.7–78.8) | ||

| Histological differentiation | Good | 637 (94.8%) 95 CI (92.8–96.2) | 21 (87.5%) 95% CI (69–95.7) | 0.125 |

| Poor | 35 (5.2%) 95% CI (3.7–7.2) | 3 (12.5%) 95% CI (4.3–31) | ||

| TNM stage | 0–I–II | 428 (67%) 95% CI (63.2–70.5) | 12 (50%) 95% CI (31.4–68.6) | 0.053 |

| III–IV | 211 (33%) 95% CI (29.5–36.8) | 12 (50%) 95% CI (31.4–68.6) | ||

| Tumour size (cm) | 4.46 95% CI (4.3–4.6) | 3.17 95% CI (2.7–3.6) | <0.001 | |

| Age (50 years) | 71.2 95% CI (70.2–71.9) | 72.38 95% CI (66.5–78.3) | 0.604 | |

| Sex | F 268 (39.8%) 95 CI (36.4–53.5) M 406 (60.2%) 95% CI (56.5–63.8) | F 12 (50%) 95% CI (31.4–68.6) M 12 (50%) 95% CI (31.4–68.6) | 0.315 | |

F: female; M: male.

Proximal colon includes caecum, ascending and transverse colon. Distal colon includes left colon, sigmoid and rectum.

Good differentiation includes G1 and G2. Poor differentiation includes G3.

In our study, we found 24 patients (3.6%) who had developed CRC despite having undergone colonoscopy within the previous 5 years; although small, this risk should be mentioned in the patient informed consent form. Among the possible aetiologies, we observed that in more than half of cases (58.4%), the causes were attributable to factors related to the procedure itself, and were therefore preventable. This phenomenon is also described in publications on the subject.8,9,14,15 As reported by other authors,14,16–18 most post-colonoscopy CRCs detected in our series were located in the proximal colon (62.5%). Post-colonoscopy CRCs were smaller, with a tendency to present earlier tumour stages compared with the control group. These findings are consistent with those described in the literature.8–10 However, in a recently published study in Canada,19 the authors detected a more advanced stage in their post-colonoscopy tumours, with poorer surgical outcomes and worse response to cancer treatment. In line with other authors, we found no differences in terms of age and sex.15

Possible causes of post-colonoscopy colorectal cancers- 1.

Previous studies16–18 attribute the onset of post-colonoscopy CRC to endoscopist-related factors. A precursor lesion detection sensitivity variable based on the endoscopist's speciality (general practitioner, surgeon, gastroenterologist) and the setting (teaching hospital, non-teaching hospital or outpatient clinic) has been observed. In our study, all the endoscopies (index and diagnostic) were performed in a teaching hospital by experienced gastroenterologist endoscopists.

- 2.

Another important factor was reported by Kaminski et al.20 and Corley et al.,21 who considered each endoscopist's adenoma detection rate to be the only risk factor for failed precursor lesion detection. Endoscopists with an adenoma detection rate below 20% would be more likely to overlook adenomatous precursor lesions or early CRCs. Unfortunately, we do not have the adenoma detection rate of endoscopists from our centre, and so were unable to calculate the risk of onset of post-colonoscopy CRC.

- 3.

Proper bowel preparation and caecal intubation—both quality indicators for colonoscopy22—are essential for the detection of adenomas. Le Clercq et al.8 attribute 19.7% of their post-colonoscopy CRCs to inadequate preparation or incomplete colonoscopy. Other authors9,14,23 also attribute their post-colonoscopy CRCs to poor colonoscopy quality.

- 4.

Cooper et al.24 found diverticular disease to be associated with an increase in post-colonoscopy CRC in all colonic segments, and Bressler et al.16 consider it an independently associated factor. This is not only because diverticular disease makes the examination difficult, but also because the endoscopic appearance of the adenomatous or tumour mucosa can be confused with the diverticular inflammation itself. In our series, 2 patients presented diverticuli in the index examination, although the colonoscopy report made no mention of a particularly difficult examination.

- 5.

Another important aetiology described in the literature is incomplete polyp resection.13–15 Fragmented removal cannot ensure complete resection of the lesion,15 and for this reason it has been considered an avoidable risk factor in post-colonoscopy CRCs.14 Pohl et al.,25 in a prospective study especially designed to detect incomplete resection of neoplastic polyps, detected up to 10% incomplete resections. Likewise, Pabby et al.13 attributed 3 (23%) of their post-colonoscopy CRCs to this cause. In our study, 4 cases (16.6%) were attributed to incomplete polyp resection, since the tumours developed in the same area where polyps had previously been resected.

- 6.

We attributed 1 of our cases to “failed biopsy detection”, since the endoscopist warned of the possibility of degeneration of the excised sessile polyp but it was not detected in the sample sent to histopathology. If the histological study had revealed high grade dysplasia or carcinoma, an early colonoscopy would have to have been performed to reassess the base. In the study by Pabby et al.,13 3 of the CRCs had endoscopic suspicion of malignancy with no histological confirmation.

Despite the algorithm described by Pabby, it is not always easy to know if the adenoma or CRC were present in the index colonoscopy or if they are new, rapidly-growing tumours. CRCs located in the right colon are often flat tumours and are more likely to progress to malignancy through the serrated neoplasia pathway more rapidly than through the classic adenoma-carcinoma suppressor pathway.26 In our series, more than half of post-colonoscopy CRCs were located in the proximal colon (62.5%). Seven of these were classified as “new”. We can speculate, as Nishihara et al.27 found in their interval cancers, that these CRCs have their origin in serrated sessile adenomas and have developed through the mutator pathway (microsatellite instability), the methylator pathway, or the CpG island methylator pathway in a shorter period of time. Nevertheless, for now, clinical studies in this respect are limited, and many questions regarding the transition of serrated polyps to cancer remain unanswered.28

Our study as several limitations: unavoidable bias, specifically in patient selection, is inherent to the retrospective nature of the study, since we only included data from the endoscopic register and not the histopathology register. Thus, patients who underwent emergency surgery or were referred directly to palliative care without colonoscopy were not included. Secondly, since we do not have a detailed family history of patients with post-colonoscopy CRC, we do not know if any of them met clinical criteria for suspecting and diagnosing hereditary non-polyposis CRC. Furthermore, in our study, we did not perform molecular genetic studies (microsatellite instability, BRAF gene or methylator phenotype) in the post-colonoscopy CRCs to determine the possible carcinogenesis pathway. Although the quality of the colonoscopy preparation was reported without the use of a validated scale, it was based in all cases on the opinion of the same endoscopists. Finally, although we do not have the adenoma detection rate of the 7 endoscopists in the index colonoscopy, all are professionals with extensive experience.

The strengths of our study are, firstly, the fact that this is the first Spanish study to describe the rate of post-colonoscopy CRC. Although the results are probably not generalisable to the rest of the population, the sample size and the tertiary teaching hospital setting support the importance of this study. Secondly, it should be noted that both endoscopies, index and diagnostic, were performed by the same group of endoscopists.

In conclusion, in our series, the post-colonoscopy CRC rate was 3.6%. A considerable proportion (58.4%) of these CRC were most likely due to preventable causes. These findings reaffirm the importance of adapting to quality indicators to reduce the risk of post-colonoscopy CRC.21,29

FundingThis study received no funding.

Conflict of interestsNone of the authors have any conflict of interests.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-Rebollo ML, del Olmo-Martínez L, Velayos-Jiménez B, Muñoz MF, Álvarez-Quiñones-Sanz M, González-Hernández JM. Etiología y prevalencia de los cánceres colorrectales poscolonoscopia. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:647–655.

This manuscript was presented as an oral poster at the Spanish Society for Digestive Diseases (SEPD) congress, Seville (Spain), June 2015.