Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease characterized by multisystem involvement, including the gastrointestinal tract.1 Gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain are common in patients with SLE and can arise from multiple causes.1 Lupus enteritis is a rare, poorly understood and potentially severe cause of abdominal pain in SLE.2,3 Hydronephrosis is also a rare complication of SLE, usually associated with bladder and/or gastrointestinal involvement (63.3% of cases).1,4

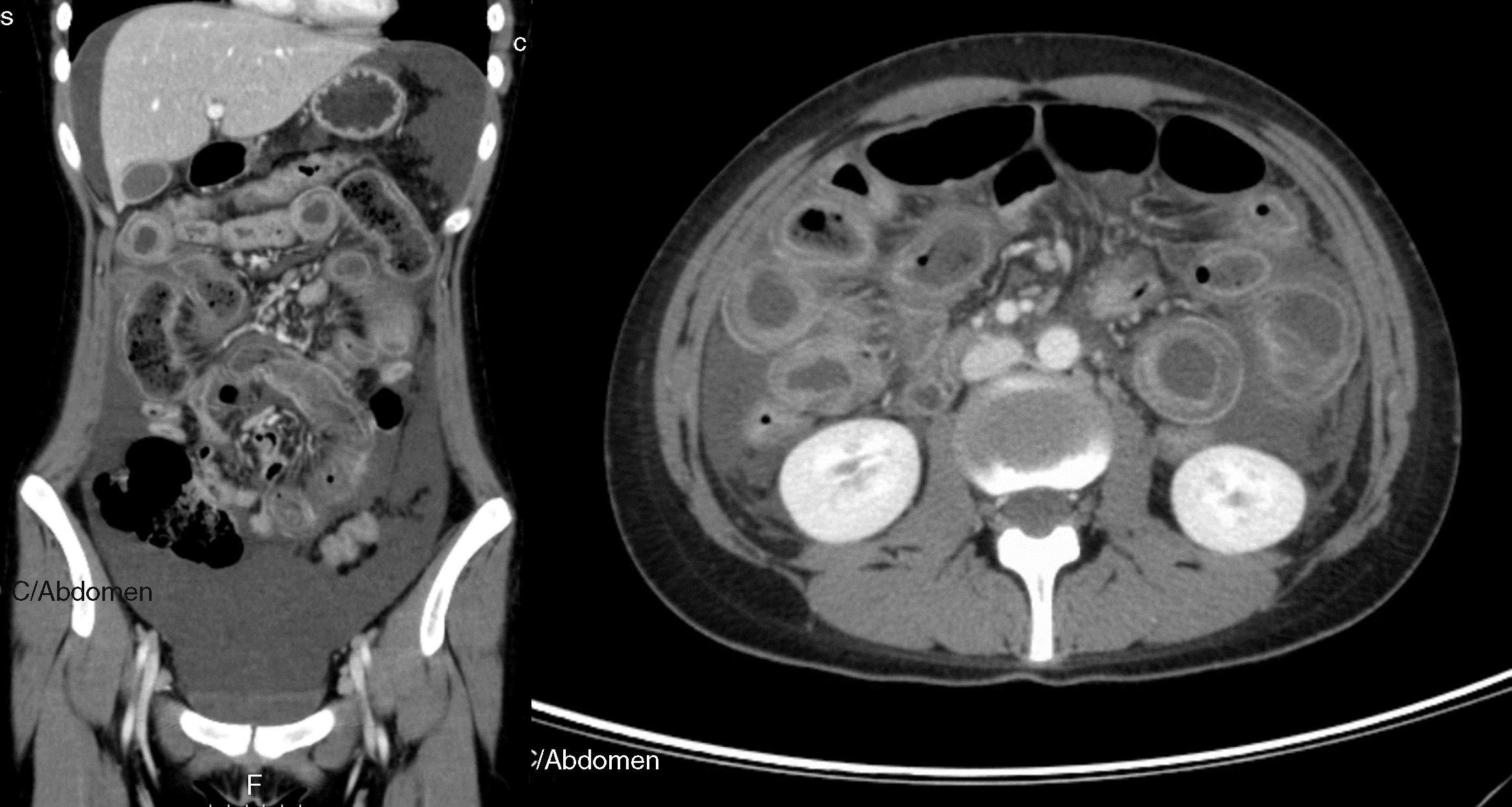

An 18-year-old woman with a 1-year diagnosis of systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) was under hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) 400mg and prednisolone 5mg daily. She was diagnosed with SLE based on cutaneous involvement (malar rash, diffuse hair loss, recurring nasal sores), arthritis, lymphopenia and positivity for antinuclear and anti-dsDNA antibodies. She was admitted with a 5-day history of lower abdominal pain and diarrhoea (5 bowel movements/day). Two weeks before admission, an acute pyelonephritis was diagnosis with bilateral hydronephrosis without no evidence of obstruction, treated with 8-day course of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 875mg/125mg. Physical examination revealed abdominal tenderness in the lower quadrants. Laboratory analysis showed lymphopenia (600/mm3), normocytic and normochromic anaemia (Hg-11.4g/dL), and C-reactive protein of 2.35 (N<0.5mg/dL). Antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin and anti-β2-glycoprotein I antibodies and lupus anticoagulant) were negative. She had a mild activity of SLE (SLEDAI: 4). Plain abdominal X-ray showed multiple air-fluid levels in the small bowel loops and abdominal ultrasonography revealed voluminous ascites, enlarged lymph nodes along iliac vessels and bilateral hydronephrosis. Urinalysis was negative for infection. Mononucleosis spot and pregnancy tests were negative. Diagnostic paracentesis was performed showing serum ascites albumin gradient <1.1g/dL with negative culture. A provisional diagnosis of mesenteric lymphadenitis was presumed and the patient received antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin. Due to lack of improvement within four days, a contrast-enhancement abdominal-pelvic computed tomography (CT) was performed showing voluminous ascites, diffuse and circumferential oedematous thickening of the small bowel wall with luminal dilation and abnormal parietal enhancement as “target sign”, compatible with lupus enteritis (Fig. 1). She started IV methylprednisolone (1g/day for three days) followed by oral prednisolone 1mg/Kg/day. Supportive measures were also attempted, including bowel rest, IV fluids, proton pump inhibitor and low-molecular-weight heparin. She had a dramatic improvement within three days. Oral prednisolone was rapidly tapered until 5mg/day and continued daily HCQ 400mg. Plain abdominal X-ray and abdominal ultrasonography within ten days of steroids therapy onset showed a resolution of the aforementioned lesions. No relapse was observed during 6-month follow-up.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal-pelvic computed tomography scan showing voluminous ascites, diffuse and circumferential oedematous thickening of the small bowel wall with luminal dilation and parietal enhancement as “target sign”, compatible with lupus enteritis (axial and coronal views).

Clinical features of lupus enteritis are unspecific, with abdominal pain being the major symptom.1–4 CT scanning has become the gold standard for diagnosis of this condition, including bowel-wall thickening, bowel dilation, ascites and abnormal bowel wall enhancement, known as “target sign”.1–3 However, some other conditions may mimic lupus enteritis, such as pancreatitis, mechanical bowel obstruction, peritonitis, inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal ischemia. Bowel involvement is usually multisegmental, with jejunum and ileum being the most commonly involved sites.1–4 Abdominal imaging is useful in diagnosis and ruling out other conditions with similar symptoms. Abdominal ultrasonography can be used as a simple and radiation-free imaging technique during follow-up to confirm clinical resolution.2 This condition is typically steroid-responsive with an overall excellent prognosis.1–4 A definitive diagnosis is based on clinical and imaging features, and the dramatic response to steroids.2–5 Early diagnosis, prompt therapy and close surveillance for perforation and peritonitis are crucial to reduce morbidity and mortality.2,4

Author's contributionsMarta Gravito-Soares and Elisa Gravito-Soares contributed equally, writing the manuscript and reviewing the literature. Marta Gravito-Soares is the article guarantor. Manuela Ferreira and Luis Tomé critically reviewed the manuscript.

Informed consentThe informed consent was obtained for this case report.

Conflicts of interestNone to declare.