Pharmaceutical companies fund most clinical trials on drugs. However, there are clinical issues that might not be a priority from a commercial point of view, but that should certainly be addressed, given their importance for patients and society in general. Independent clinical research represents a fundamental pillar here and its basic element is investigator-initiated studies/trials. In these studies, it is the researcher who conceives the idea, develops the project and also acts as the sponsor. Most researchers are familiar with participating as collaborators in studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. In these studies, the company is in charge of all the scientific, legal and financial aspects, leaving the responsibility of the researcher mainly limited to the inclusion of patients and compliance with the protocol. On the contrary, the start-up and development of an independent research study requires considerable resources – of knowledge, money and time – and careful planning on the part of the researcher. In this manuscript, we will review the main characteristics of the studies initiated by the researcher and their fundamental differences with those sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. We will also outline what its strengths and limitations are. Finally, we will propose some solutions to the main challenges they pose. Our ultimate goal is to stimulate potential researchers to undertake the challenge of conducting an independent clinical research project.

Las compañías farmacéuticas financian la mayoría de los estudios clínicos sobre medicamentos. Sin embargo, existen cuestiones clínicas que podrían no ser prioritarias desde el punto de vista comercial, pero que sin duda deberían ser abordadas, dada su transcendencia para los pacientes y la sociedad en general. La investigación clínica independiente representa aquí un pilar fundamental y su elemento básico son los estudios iniciados por el investigador (también conocidos por su nombre en inglés, investigator-initiated studies/trials). En estos estudios, es el investigador el que concibe la idea, desarrolla el proyecto y además actúa como promotor. La mayoría de los investigadores están familiarizados con la participación como colaboradores en los estudios promovidos por las compañías farmacéuticas; en dichos estudios, la compañía se encarga de todos los aspectos científicos, legales y, además, económicos, quedando la responsabilidad del investigador limitada fundamentalmente a la inclusión de pacientes y cumplimiento del protocolo. Por el contrario, la puesta en marcha y desarrollo de un estudio de investigación independiente requiere considerables recursos ―de conocimientos, económicos y de tiempo― y una cuidadosa planificación por parte del investigador. En el presente manuscrito revisaremos cuáles son las principales características de los estudios iniciados por el investigador y sus diferencias fundamentales con los promovidos por la industria farmacéutica. Nos plantearemos también cuáles son sus fortalezas y sus limitaciones. Por último, propondremos algunas soluciones a los principales desafíos que plantean. Nuestro objetivo final es estimular a los potenciales investigadores a acometer el reto de llevar a cabo un proyecto de investigación clínica independiente.

Research is an activity aimed at obtaining new knowledge and applying it to solve problems or day to day issues. Scientific research, in particular, uses the scientific method to study a given aspect of reality, either theoretically or experimentally.1

Pharmaceutical companies fund most clinical trials of medicinal products, especially when it comes to randomised clinical trials targeting initial approval of a particular drug.2 However, there are numerous clinical issues that might not be a priority from a regulatory or strictly commercial point of view, but that should certainly be addressed, given their importance for patients and society in general.

Independent clinical research therefore represents a fundamental pillar here and its basic element is investigator-initiated studies (IIS) also known as independent clinical studies.

An IIS is a study in which it is the researcher who conceives the idea, develops the project and acts as the study sponsor3 (in reality, this last role is often held by the organisation, usually non-profit, to which the investigator belongs, such as, for example, a scientific society or health research institute). Thus, the responsibilities of the researcher-sponsor include the full spectrum of a research study: from its conception and design, through the development and coordination of the study, to the analysis of the data and publication, not forgetting the provision and management of funds, the legal responsibilities of the sponsor and the administrative procedures pertaining to the Independent Ethics Committee (IEC) and the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios [Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices] (AEMPS).

Most researchers are familiar with participating as collaborators in studies sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. In these studies, the company is in charge of all the scientific (designing the protocol, etc.), legal (interactions with the health authorities) and financial (study funding) aspects, leaving the responsibility of the researcher mainly limited to the inclusion of patients and compliance with the protocol.4

On the contrary, the start-up and development of an IIS requires considerable resources―of knowledge, money and time―on the part of the principal investigator. We therefore need to be sure it is worth the effort of embarking on an endeavour of such magnitude. Therefore, in this manuscript we will first review the main characteristics of IISs and their fundamental differences with studies sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. We will also outline what their strengths and limitations are. Finally, we will propose some solutions to the main challenges posed by independent clinical research. Our ultimate goal is nothing other than to stimulate potential researchers to undertake the challenge of conducting an IIS.

What are the main differences between a study sponsored by industry and by an independent researcher?Role of investigatorIn most industry-sponsored studies, the investigator plays a relatively passive role, with functions mainly limited to the recruitment of patients and application of the predetermined protocol. On the contrary, in IISs, the principal investigator plays a leadership role and a central role intellectually.

Study objectivesAlthough the objectives of both types of study may overlap (in fact, they do in many cases), the goal of clinical trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry is often related to the registration/approval of medicinal products, with the sponsoring company owning the data. In IISs, on the other hand, the objective is fundamentally scientific and the results are owned by the investigators (in reality, by the non-profit organisation to which the principal investigator belongs, which often acts as sponsor). In other words, in the first case the hope is that the development of new drugs, in addition to offering new therapeutic alternatives, will generate financial benefits, while in the second scientific motivation plays the dominant role.

Thus, industry-sponsored studies are usually in pursuit of approval for a new medicinal product.5,6 It needs to be said here that this industry objective contributes very positively to the advance of medicine and the improvement of patient treatment, being essentially the source of new drug development. For their part, IISs seek to answer questions that are relevant to clinical practice that would otherwise likely not be covered by industry research.7 Although studies of both types may share an interest in the same drug, IISs help to generate data on the effectiveness and safety of an already-approved medicinal product in a real-world setting (e.g. in new indications or dosing regimens that differ from those of the initial approval). Thus, in general, the focus of IISs is on optimising existing treatments, including comparing them with other therapeutic strategies (from both an effectiveness and an efficiency point of view) or the assessment of long-term safety (remember that industry-sponsored clinical trials often have time-limited follow-up).

To summarise, investing in independent clinical research benefits the patient in particular and society in general, in terms of the reduced impact of diseases, optimisation of healthcare strategies and curtailment of health systems costs. All of these benefits provide an excellent complement to those derived from industry-sponsored research.

Study inclusion criteriaThe criteria for inclusion in industry-sponsored clinical trials are usually very strict, as the conditions under which drugs are evaluated must generally be tightly controlled. As a consequence, the populations assessed are very selective and it is difficult to extrapolate the results to the real world.8 On the contrary, IISs should cover broader populations and generate knowledge on the role of treatments in real life.

Study fundingIn studies sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, the industry sponsors and funds the trial. The costs of clinical trials are often considerable, since they include, among other items: paying for researchers and their meetings, designing the research project, creating the case report form (CRF), the insurance policy, fees for submission to IECs and the AEMPS, administering the study drug, paying for additional tests (not performed in clinical practice), preparing periodic reports, monitoring, etc.9,10 This means that for IISs, the researcher must seek funding through public calls for proposals or from the pharmaceutical companies themselves.

Financial benefit for the researcherIn general, interest in the research and commitment to scientific development is primarily what motivates researchers to participate in studies sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry. Nevertheless, these projects also carry a financial incentive in the form of remuneration for the effort involved in taking part. However, most IISs lack this type of financial remuneration for researchers (as we discussed above, the needs of these studies are many and the resources available are few). Therefore, the principal investigator can only count on scientific interest in their idea to convince and motivate collaborating investigators to participate.8

Quality of monitoring and study resultsThe quality of the data included in a research study, whatever its nature, must be excellent; only then will quality results be obtained. In this vein, it has been suggested that, on average, industry-sponsored studies are submitted to the regulatory authorities in a more correct and complete manner and carry out more rigorous tracking of study documentation, as well as data monitoring, compared with IISs.11–13 This may be due to various factors: firstly, independent researchers’ training in good clinical practices is, perhaps, less than that of the more “professionalised” study sponsors in the pharmaceutical industry; secondly, the financial resources required to monitor the study’s development and the quality of the data obtained are very great and, generally, unattainable for independent investigators.

It has been proposed that the quality of the evidence generated by studies may differ depending on who the sponsor is; in this sense, some authors have found that industry-sponsored clinical trials more often have a double-blind design.14

Moreover, it has been suggested that there may be a higher probability of demonstrating a benefit of the drug studied in industry-sponsored clinical trials compared with IISs,15–19 although this observation has not been confirmed by other authors.20–22 In this vein, a recent Cochrane review examined the effects of industry sponsorship on the frequency of favourable results and risk of bias, finding no association whatsoever.23 Finally, if we consider publication of a clinical trial as a quality criterion, it appears that industry-sponsored studies do not appear in publications in biomedical journals more than those initiated by researchers.24 What does appear to be confirmed is more detailed reporting of adverse events in the case of industry-sponsored studies.12

In summary, the type of study sponsor―industry or researcher―should not per se be a determining factor in its quality. We need to work on the culture of the scientific method and ethical principles, and take into account the resources needed to monitor the development of studies and the data recorded, so that the quality of IISs can match that of industry-sponsored studies. It is indisputable that transparency and open publication of original data in both types of study will increase their quality and make them more comparable.

What are the fundamental clinical advantages of independent clinical research?Independence from the pharmaceutical industryThere is no doubt that one of the advantages of IISs is that they offer us a chance to be independent of the industry throughout the study process, including the design, analysis and interpretation of the results, drawing conclusions, and finally, publication in the corresponding biomedical journal25; all this regardless of whether we believe, a priori, that the results are going to be positive or negative for the pharmaceutical industry and also regardless of whether the study’s results will ultimately be beneficial or detrimental to the owner of the drug in question.

Central role of researchers in the studyIISs offer their principal investigators the opportunity to be authentic leaders of a research project, with all the personal and intellectual stimulation that brings. Moreover, it is likely that the scholarly impact of publishing an independent clinical research article is greater than that of an industry-sponsored one, being interpreted as more commendable and entailing greater scientific leadership.26

Clinical relevance of the researchWithout doubt, the results of an industry-sponsored clinical trial can have enormous clinical relevance for patients, who will benefit from the development of efficacious new drugs. However, there are aspects that are very relevant to patients, and by extension to researchers, that would never be addressed if not for IISs. Exploration of clinical aspects that may not be of interest―commercially speaking―to industry-sponsored studies enables us to adequately fill in the spectrum of research into a particular drug.27

Extrapolation of results to clinical practiceAs has been mentioned above, due to the customary breadth and looseness of the inclusion criteria of IISs (in contrast with the more restrictive nature of industry studies), results from independent research can reasonably be extrapolated to clinical practice.

Creation of synergies with other researchersOrganising an IIS, which usually requires a multicentric design, means creating an infrastructure that, even after the end of the trial in question, can continue to be of great use for conducting future studies.28,29 The incessant selective pressure on researchers (particularly in Spain) has spawned a symbiotic evolution that has enabled us to survive this environmental pressure.30 One of the most representative examples of this collaboration is the Centros de Investigación Biomédica en Red [Network of Biomedical Research Centres] (CIBER) (and more specifically the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Enfermedades Hepáticas y Digestivas [Liver and Digestive Diseases Networking Biomedical Research Centre], CIBEREHD), of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Institute of Health] (ISCIII). Indeed, this growing network collaboration is one of the most important strengths of gastroenterology in Spain.30 If one conclusion can be drawn from the Spanish experience, it is that collaboration between institutions and networks of researchers is the most profitable strategy for improving the quantity and, more importantly, the quality of research. There is no doubt that teamwork yields great results. Coming together gives us strength, and this is especially true in research.1,31

When we contemplate conducting a multicentre IIS, we should consider that in many cases it takes almost the same effort to organise it with a few centres in our area (e.g. our city) as at the national level (with multiple autonomous regions). Obviously, this is not always the case, although sometimes making that extra effort to expand our borders is worth it, as we can obtain faster results and, above all, increased relevance and scientific impact. In turn, organising an IIS can strengthen the sponsoring centre’s research team, facilitate its funding, and ultimately contribute to its sustainability.

What are the fundamental challenges of independent research and their possible solutions?IISs face a series of barriers to their realisation, that in general are similar anywhere in the world.5,32,33 Below, we review these limitations and propose possible solutions to them.

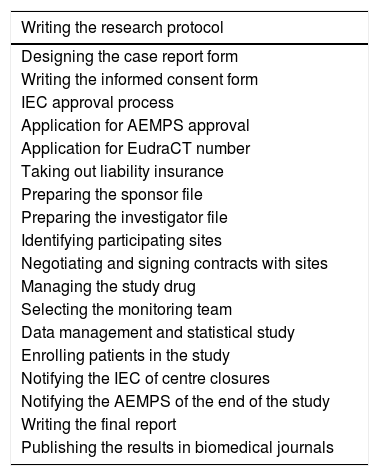

Limited research timeConceiving, organising and carrying out an IIS entails an enormous effort and requires a very significant dedication of time to both administrative tasks and scientific coordination.34Table 1 summarises the numerous legal and administrative procedures required to launch a clinical trial.35

Legal and administrative procedures required to launch a clinical trial.

| Writing the research protocol |

|---|

| Designing the case report form |

| Writing the informed consent form |

| IEC approval process |

| Application for AEMPS approval |

| Application for EudraCT number |

| Taking out liability insurance |

| Preparing the sponsor file |

| Preparing the investigator file |

| Identifying participating sites |

| Negotiating and signing contracts with sites |

| Managing the study drug |

| Selecting the monitoring team |

| Data management and statistical study |

| Enrolling patients in the study |

| Notifying the IEC of centre closures |

| Notifying the AEMPS of the end of the study |

| Writing the final report |

| Publishing the results in biomedical journals |

AEMPS: Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios [Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices]; IEC: Independent Ethics Committee.

For physicians working in hospitals, who therefore have a high care workload, planning an independent clinical trial can seem almost unthinkable. For a university hospital where staff also have teaching roles, this becomes mission―almost―impossible. When we speak of the time requirements for the researcher, we are referring not only to conducting the study itself, but also to the preceding (study design, obtaining funding and approvals) and following steps (contact with researchers, study coordination, evaluation of results and their publication). Thus, for physician-researchers, IISs represent a very considerable increase in workload without associated remuneration.

The availability and freeing-up of clinicians’ time for research is undoubtedly a pending issue. And it will continue to be so until we manage to change the paradigm that prevails in our institutions, where research is regarded as a mere minor appendage of healthcare activity (and therefore dispensable and incidental), and it is recognised as a essential part of it, also at the organisational level. This can be achieved in two ways: on the one hand, by freeing up the clinician’s care load, and on the other hand, by delegating research project management tasks to qualified technical personnel who will surely perform them better than the researcher would.

The Instituto de Salud Carlos III, which manages biomedical research in Spain, has acknowledged this need and is attempting to provide some type of remedy through the so-named “contracts for the intensification of research activity”. However, the chances of success with one of these grants are limited in view of the stiff competition and they do not solve the problems faced by most clinician researchers. Freeing up part of the day through own funds may be a solution for some researchers: money enables us to buy time.1 And this brings us precisely to what is probably the most relevant limitation to conducting independent research: the difficulty of obtaining funding.

Difficulties obtaining fundingHigh quality clinical research is costly, among other things because it generally requires a multicentric design and the inclusion of a considerable number of patients. This high cost is the main reason why the pharmaceutical industry funds most clinical trials, with less ambitions designed often being the only option attainable for independent researchers.

Public calls for proposals are fundamental for obtaining funding to carry out independent research.36,37 In Spain, for example, this type of research is funded by competitive public calls for proposals sponsored by institutions such as the ISCIII. Specifically, for years a specific call has existed for independent clinical research projects (“Grants for the promotion of independent clinical research with medicinal products for human use or advanced therapies, through the funding of projects not sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry”). As is expressed in this call, projects are eligible for funding if they seek to conduct clinical trials (preferably phase i, ii or iii) that would enable tangible advances to be made for patients and that would provide evidence to the authorities for their introduction in the National Health System. Health research institutes (to whom special consideration is given), other public or private healthcare institutions and organisations (in this case, non-profits and those with ties to or set up within the National Health System) and the CIBER can all be beneficiaries of this intervention. In the projects submitted, the role of sponsor must be held exclusively by the managing body of the institution applying. The budget directed towards this call for proposals this year was approximately 19 million euros, and the deadline for carrying out projects for this funding is four years.

Public calls for proposals are highly competitive, so it is difficult to obtain funding through them. It is therefore necessary to explore other alternatives, including in particular obtaining funds from the pharmaceutical industry itself through calls for investigator-initiated studies. A recently-conducted survey of 28 pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies revealed that 90% of them hold calls of this type for independent research.32 In this type of study, the researcher is the sponsor (and, therefore, assumes the legal responsibilities), with the pharmaceutical company merely providing financial backing (even, on occasions, limited to providing the study drug). This type of grant is used as backing for preclinical and clinical studies (both interventional and non-interventional) that in some way involve the active substance of the pharmaceutical company in question. The study would need to be truly independent, i.e. conceived spontaneously by the researcher with no “inducement” of any kind by the pharmaceutical company to research any aspect in which the latter has a particular interest and is thus attempting to use the “independent” researcher to merely implement its own idea. Therefore, al least ideally, whether or not the company will benefit from she study’s results should not be a criterion on which it bases awards.38,39 Obviously, this philosophy of collaboration between companies and researchers is perfectly compatible with the pharmaceutical company obtaining a benefit, for example, obtaining information on the use of its drug in other diseases not previously approved, or with dosing regimens not included in the summary of product characteristics, or simply in patients treated in routine clinical practice.

This is why it is accurate to say that research funded and sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry and independent research are complementary. In this regard, our philosophy―that of all our group―is underpinned by the idea that all the funds obtained from projects should be reinvested in research, be it on human resources or logistics, which is what makes the group sustainable in the long-term.

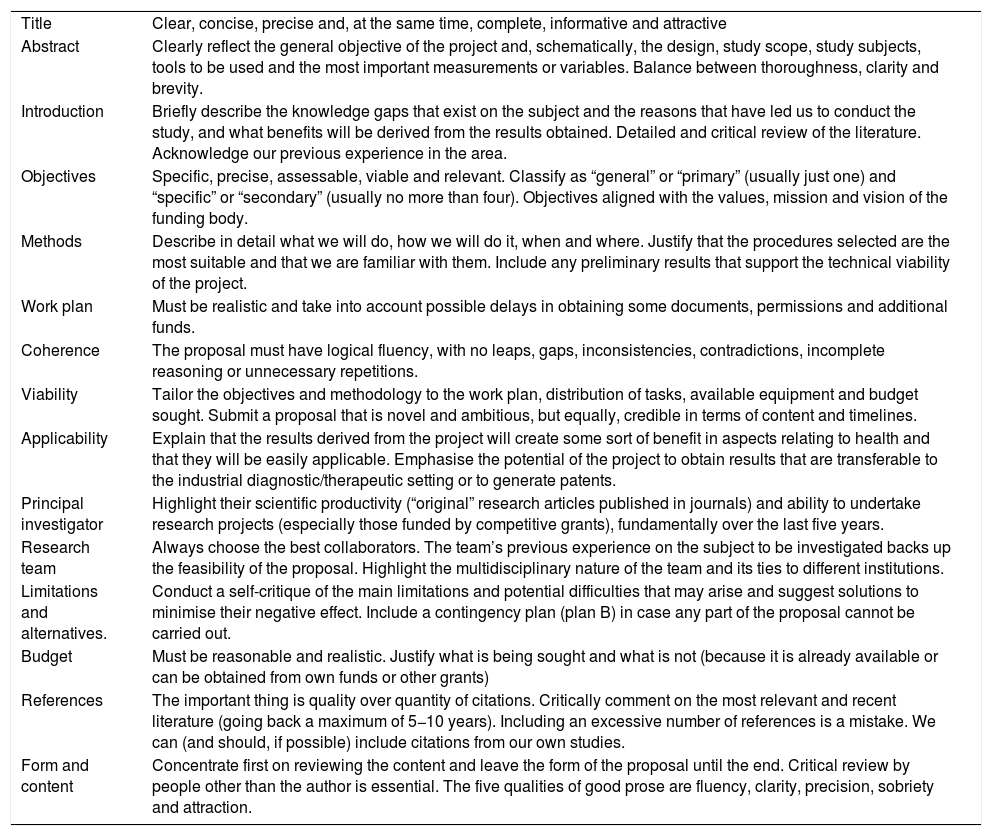

Writing the research proposalThe first obstacle the researcher faces in carrying out an IIS is in properly writing the research proposal.40 Being capable of preparing a good research proposal is a requirement in order to successfully compete for funding. The research proposal is a meticulously written plan that covers all scientific, ethical and logistical aspects of the study we are proposing. The aim of this proposal is to introduce and describe in detail what is going to be researched, the theoretical basis of the concept, the methodological components and human, technical and financial resources that will be necessary to conduct the investigation. The research proposal is the culmination of all the work carried out in the planning stage of the research and serves as a guide for the researchers during the study. Writing a good research proposal is the best guarantee of success. Table 2 includes a series of recommendations for properly writing and submitting a research proposal.41

Key points to writing an adequate research proposal.

| Title | Clear, concise, precise and, at the same time, complete, informative and attractive |

| Abstract | Clearly reflect the general objective of the project and, schematically, the design, study scope, study subjects, tools to be used and the most important measurements or variables. Balance between thoroughness, clarity and brevity. |

| Introduction | Briefly describe the knowledge gaps that exist on the subject and the reasons that have led us to conduct the study, and what benefits will be derived from the results obtained. Detailed and critical review of the literature. Acknowledge our previous experience in the area. |

| Objectives | Specific, precise, assessable, viable and relevant. Classify as “general” or “primary” (usually just one) and “specific” or “secondary” (usually no more than four). Objectives aligned with the values, mission and vision of the funding body. |

| Methods | Describe in detail what we will do, how we will do it, when and where. Justify that the procedures selected are the most suitable and that we are familiar with them. Include any preliminary results that support the technical viability of the project. |

| Work plan | Must be realistic and take into account possible delays in obtaining some documents, permissions and additional funds. |

| Coherence | The proposal must have logical fluency, with no leaps, gaps, inconsistencies, contradictions, incomplete reasoning or unnecessary repetitions. |

| Viability | Tailor the objectives and methodology to the work plan, distribution of tasks, available equipment and budget sought. Submit a proposal that is novel and ambitious, but equally, credible in terms of content and timelines. |

| Applicability | Explain that the results derived from the project will create some sort of benefit in aspects relating to health and that they will be easily applicable. Emphasise the potential of the project to obtain results that are transferable to the industrial diagnostic/therapeutic setting or to generate patents. |

| Principal investigator | Highlight their scientific productivity (“original” research articles published in journals) and ability to undertake research projects (especially those funded by competitive grants), fundamentally over the last five years. |

| Research team | Always choose the best collaborators. The team’s previous experience on the subject to be investigated backs up the feasibility of the proposal. Highlight the multidisciplinary nature of the team and its ties to different institutions. |

| Limitations and alternatives. | Conduct a self-critique of the main limitations and potential difficulties that may arise and suggest solutions to minimise their negative effect. Include a contingency plan (plan B) in case any part of the proposal cannot be carried out. |

| Budget | Must be reasonable and realistic. Justify what is being sought and what is not (because it is already available or can be obtained from own funds or other grants) |

| References | The important thing is quality over quantity of citations. Critically comment on the most relevant and recent literature (going back a maximum of 5−10 years). Including an excessive number of references is a mistake. We can (and should, if possible) include citations from our own studies. |

| Form and content | Concentrate first on reviewing the content and leave the form of the proposal until the end. Critical review by people other than the author is essential. The five qualities of good prose are fluency, clarity, precision, sobriety and attraction. |

Another challenge the researcher faces in the initial phases of an IIS is designing the CRF.35 Although it may not seem so, this is a crucial phase and its quality will have significant impact on the quality of the results ultimately obtained. In other words, a poorly-designed CRF will obviously collect poor-quality data. The CRF must be based on the protocol (thus, if information is missing from the CRF, it is the protocol that is incomplete). Every effort must be made to select data that are relevant to the study, but only those that are truly necessary. As drastic as it seems, this must be the CRF designer’s golden rule and they must be prepared to uphold it, because the temptations to violate it will be constant. Here, quantity and quality are frequently incompatible. Redundant or duplicate questions should be avoided. We should not ask for data that can be extrapolated from others already included. Simple, clear language should be used, with unambiguous sentences, avoiding abbreviations where possible. It is important for the CRF to be reviewed by different members of the research team (monitors, managers, statisticians, etc., as well as, obviously, the principal investigator) before it is finalised. Making significant changes to the CRF once the trial is underway is costly and risky, so it is worth taking the time to get it right from the start. Finally, it should be noted that a good CRF will notably facilitate subsequent monitoring tasks.42

The advent of electronic CRFs has been an important advance in this field. Having reached this point, it seems relevant to briefly comment on REDCap (https://www.project-redcap.org/), the acronym for Research Electronic Database Capture.43 In particular, the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology]—REDCap collaborative research online platform is a piece of software for designing, developing and managing electronic CRFs for research studies. It is an intuitive tool to use (for both researchers and monitors), offering superior capabilities and services to those of most private contractors. Moreover, it provides the tools necessary for efficient data analysis, online statistics generation, monitoring, collecting data on mobile devices and a multitude of extra functions. This platform significantly reduces the costs of a traditional CRF and thereby encourages the development of investigator-sponsored projects, independently of the interests of private industry (in fact, use of the software is restricted and is only permitted for non-commercial research).

Identifying participating centres and selecting collaboratorsWe should always choose the best collaborators, convincing them that our leadership is a guarantee of success for joint projects. And we should choose the number of collaborators carefully, as some say that “the success of a research project is generally inversely related to the number of people on whom it depends”. What is certain is that, as almost always, quality, and not quantity, is what matters. We should ensure that the collaborating researcher is qualified through training and experience, and has sufficient resources to conduct the clinical trial, as well as that the facilities at the site where it will be conducted are suitable.35 The most important thing is to select committed researchers, with guarantees that, for example, they will recruit the number of patients initially agreed upon. It is clear that this commitment is not always easy to honour because it depends on several factors, some of which are beyond our control.44 However, it is important to choose collaborators who are well aware of their capabilities, since, if they ultimately fail to deliver what was agreed, the viability of the project could be seriously compromised.1

Approval and classification by the Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos SanitariosThe AEMPS’ mission is to guarantee to society, from a public service perspective, quality, safety, efficacy and correct information with regard to medicines and medical devices in the broadest sense, from their research to their use, in the interest of protecting and promoting health. The fundamental role of the AEMPS is to offer guarantees with regard to medicines and medical devices, fostering scientific and technical knowledge. It is the health authority of reference when it comes to guaranteeing the quality, safety and efficacy of information about medicinal products.

With regard to the classification process for research studies, we will very briefly mention that, if the study has an experimental design, it will be classed as a clinical trial (see Royal Decree 1090/2015 of 4 December, which regulates clinical trials with medicinal products, Independent Ethics Committees and the Spanish Registry of Clinical Studies). Remember that a clinical trial is any study that meets any of the following conditions: 1) subject allocation to a particular therapeutic strategy that is not part of routine clinical practice; 2) the decision to prescribe the investigational medicinal products is taken together with that to include the subject in the clinical study, and 3) diagnostic or follow-up procedures apply to the trial subjects that go beyond those in routine clinical practice.

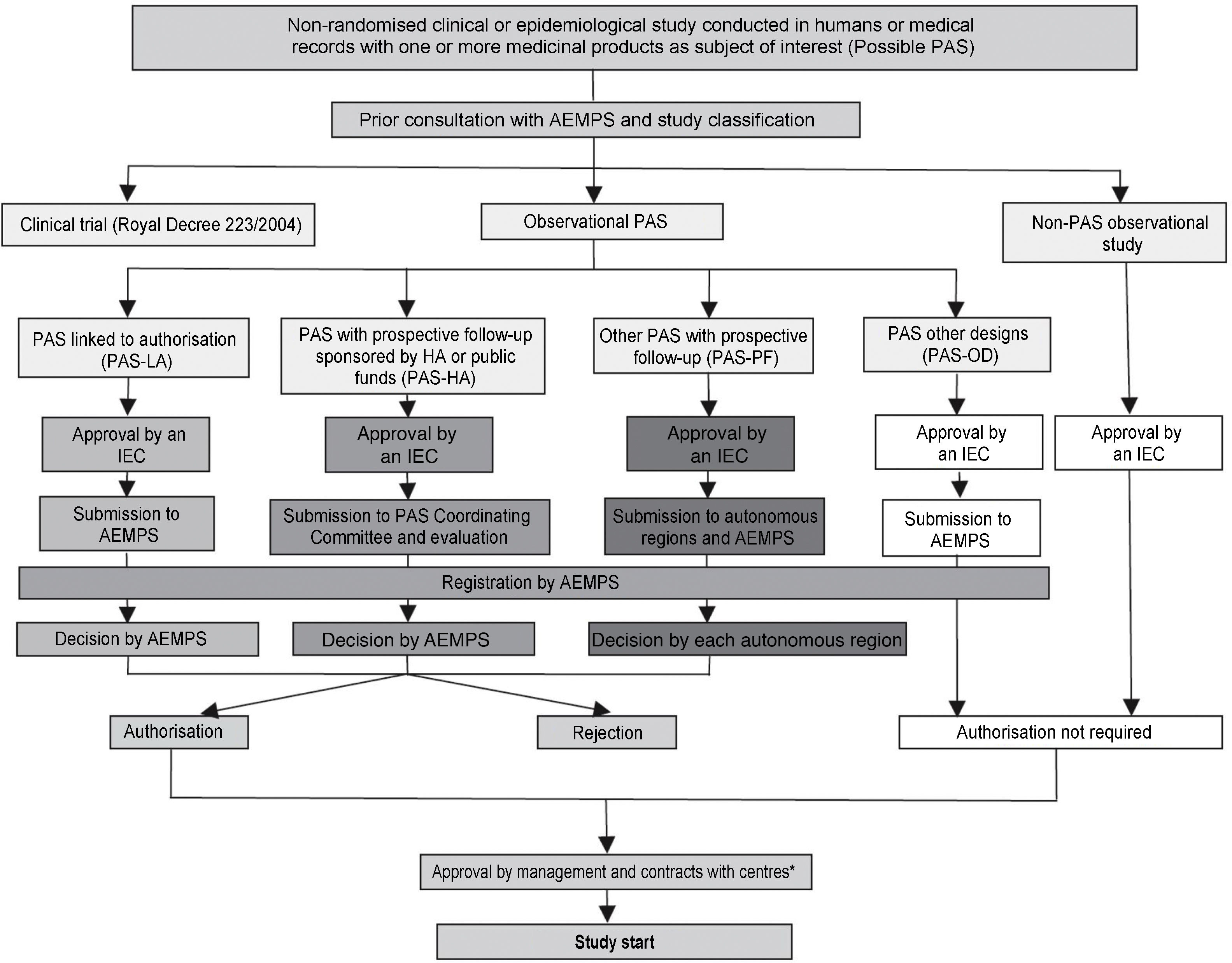

In addition, in accordance with Order SAS/3470/2009 of 16 December, publishing guidance on observational post-authorisation studies (PAS) for medicinal products for human use, the AEMPS classifies all possible PASs with medicinal products for human use. These include all non-randomised clinical or epidemiological studies conducted in humans or with medical records that collect information on medicinal products. It is worth very briefly reviewing the main characteristics and requirements of the health authorities for the four types of PAS, the administrative pathways for which are summarised in Fig. 1.

Administrative pathways for post-authorisation studies (PAS).

Reference: BOE [Spanish Official State Gazette] No. 310, Friday 25 December 2009, Sec. I, p. 109775: Order SAS/3470/2009, of 16 December, publishing guidance on observational post-authorisation studies for medicinal products for human use.

PAS-HA: post-authorisation study sponsored by the Health Authorities (HA) or funded with public funds; PAS-LA: post-authorisation study conducted at the request of the regulatory authorities and in connection with the marketing authorisation (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios or European Medicines Agency); this administrative pathway includes both studies linked to authorisation such as safety studies required by the health authorities and those included in risk management plans; PAS-OD: post-authorisation studies with designs other than prospective follow-up, e.g. cross-sectional or retrospective studies; PAS-PF: post-authorisation studies with prospective follow-up that do not correspond to any other the preceding categories; Non-PAS: studies in which the fundamental research factor under investigation is not a medicinal product; e.g. disease incidence or prevalence studies, etc.

“PAS linked to authorization” (PAS-LA): this type of PAS takes place at the request of the regulatory authorities and in connection with the marketing authorisation (by the AEMPS or the European Medicines Agency). This administrative pathway includes safety studies required by the health authorities and studies included in pharmaceutical companies’ risk management plans.

“PAS funded with public funds or sponsored by the health authorities” (PAS-HA): this is the typical administrative pathway for a clinical trial funded with ISCIII funds, or when the AEMPS itself is the study sponsor. These studies require authorisation, not merely classification, by the AEMPS. This pathway has the advantage of a simplified authorisation procedure and a single decision issued by the AEMPS within 30 days.

“PAS with prospective follow-up” (PAS-PF): these are studies where patients are selected due to their exposure and are followed up for a sufficient length of time, with the study period coming after the start of the research. They are vulnerable to being used as an instrument to induce prescription, and for this reason the rules here are particularly strict: the study must be authorised by all the autonomous regions where it is to be conducted, with the respective competent bodies making a decision within 90 days. This administrative pathway includes fee payments to each of the autonomous regions, which can noticeably increase the study’s budget.

“PAS with other designs” (PAS-OD): includes those studies without prospective follow-up (i.e. cross-sectional or retrospective studies). This administrative pathway is relatively simple, requiring only the approval of an IEC and not authorisation by the AEMPS or the autonomous regions where it is to be conducted.

Managing the research projectIn comparison with independent researchers, industry usually has a greater availability of human resources to perform the tedious procedures required for the approval and subsequent management of research projects, especially in the case of multicentre clinical trials.45,46 The management of a clinical study is more complicated than one might think, since it involves many players (sponsors, researchers, hospitals, ethics committees, health authorities, legal departments, monitors, patients, etc.). In addition, the work must be done in accordance with good clinical practices, a series of requirements that must be met and that guarantee protection or the rights, safety and wellbeing of the trial subjects, as well as the reliability of its results.

Study management is often entrusted to a Contract Research Organisation (CRO). The CRO acts as a bridge between the sponsor and the other players involved in the study. The service a CRO is able to offer can be divided based on the phase of the study. The start-up phase includes developing and reviewing the research protocol, adapting documentation to Spanish legislation, obtain the necessary approvals from ethics committees and the health authorities, designing the CRF, selecting investigators and negotiating contracts with centres. Once approval has been obtained and the clinical trial begins, the CRO offers its services to perform monitoring and pharmacovigilance. Finally, the CRO takes charge of managing the data obtained by the study, generating reports and document control and storage.

The Spanish Clinical Research Network (SCReN) is a non-profit platform to support multicentre clinical trials that brings together 31 Clinical Research and Clinical Trials Units in the 13 autonomous regions. SCReN collaborates with researchers, cooperative groups, research institute, etc. to conduct independent multicentre studies (predominantly clinical trials with medicinal products), facilitating study management and coordination, and prioritising those with funding awarded through the Acción Estratégica en Salud [Strategic Health Action] programme. SCReN is funded by ISCIII and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF).

Some scientific societies, as is the case of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis] (GETECCU), make a scientific secretary available to their members to perform clinical trial coordination/management functions, in this case in relation to inflammatory bowel disease. This person’s role is to manage all organisational aspects relating to GETECCU multicentre research studies, mainly clinical trials with medicinal products.

Finally, one very attractive option, albeit with a certain degree of organisational complexity, is for the research group to have its own trained personnel to carry out all of the aforementioned management, CRF design and monitoring functions for independent research studies. The advantage of this alternative is that said personnel will be familiar with the disease studied, the routine procedures and the research group's idiosyncrasies, and their coordination with the latter should therefore be excellent. This option is especially productive and profitable when the group’s research activity is intense and fairly continuous. In our experience, training personnel on the group’s previous projects has a positive impact on future projects, progressively increasing their efficiency. Obviously, this requires an initial investment in the future and the group must be capable of contracting specialist personnel and retaining them in the long term.

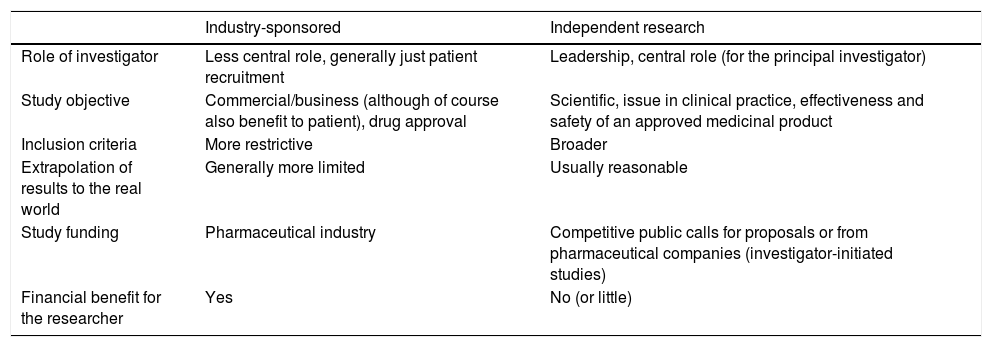

Final reflectionsResearch is a cornerstone of medical activity and it is evident that the integration of excellent clinical practice and research activity yields the highest quality of care. Being a researcher, particularly in our setting, constitutes a veritable challenge. Independent research plays a vital role in generating scientific evidence and complements the clinical trials sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry; it addresses questions relevant to patient care, questions that are not generally the main focus of research with commercial interest. It is therefore essential to develop independent clinical research that addresses matters of medical interest, even though it does not generate business profits. In this manuscript, we have reviewed the main characteristics of independent clinical research and described some of the differences between a study sponsored by industry and one sponsored by an independent researcher, as summarised in Table 3.

Main differences between a study sponsored by industry and by an independent researcher.

| Industry-sponsored | Independent research | |

|---|---|---|

| Role of investigator | Less central role, generally just patient recruitment | Leadership, central role (for the principal investigator) |

| Study objective | Commercial/business (although of course also benefit to patient), drug approval | Scientific, issue in clinical practice, effectiveness and safety of an approved medicinal product |

| Inclusion criteria | More restrictive | Broader |

| Extrapolation of results to the real world | Generally more limited | Usually reasonable |

| Study funding | Pharmaceutical industry | Competitive public calls for proposals or from pharmaceutical companies (investigator-initiated studies) |

| Financial benefit for the researcher | Yes | No (or little) |

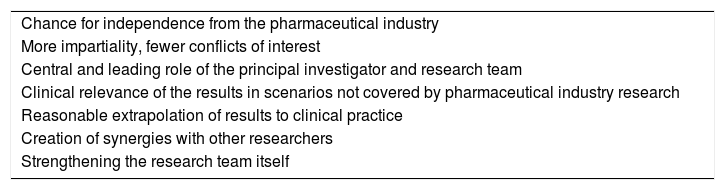

It is evident that there is a shortage of researchers with experience in conducting independent studies. Many researchers have mastered certain concepts of clinical research methodology, but the organisation and development of a clinical trial requires knowledge of many other aspects: writing protocols, CRF design, ethical and legal considerations, applications to health authorities and ethics committees, data quality monitoring, pharmacovigilance and many more. If we add to this organisational and administrative complexity the difficulty of obtaining funding and lack of financial incentive (in contrast with industry-sponsored studies), it does not come as a surprise that the number of IISs is really quite low. Nevertheless, independent research is also associated with big advantages, as can be seen in Table 4. Notable among them is the central and leadership role played by the researcher and the clinical relevance of the results obtained.

Advantages of independent clinical research.

| Chance for independence from the pharmaceutical industry |

| More impartiality, fewer conflicts of interest |

| Central and leading role of the principal investigator and research team |

| Clinical relevance of the results in scenarios not covered by pharmaceutical industry research |

| Reasonable extrapolation of results to clinical practice |

| Creation of synergies with other researchers |

| Strengthening the research team itself |

There is no doubt that independent clinical research must face numerous challenges, which we have covered in this manuscript, but we have also suggested, at least in some cases, what the solutions to these may be. It is also evident that the commitment of governments and health authorities is necessary to facilitate and incentivise IIS development, motivating and training independent researchers, increasing funding in competitive public calls for proposals and developing the infrastructure to support this research.

This independent research activity closes the circle which begins with the detection of an unmet clinical need in patients, which continues with the design of a suitable research study and ends with the application of its results to those patients. There is no doubt that this direct link between research activity and clinical practice generates notable satisfaction in the physician-researcher carrying it out, in verifying how the quality of life of our patients can be improved, which is, ultimately, our priority as physicians and researchers.

Conflicts of interestJ.P. Gisbert: scientific advice, support for research or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma, Mayoly, Allergan, Diasorin.

M. Chaparro: scientific advice, support for research or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen, Ferring, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma and Tillotts Pharma.

Please cite this article as: Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Retos y desafíos de la investigación clínica independiente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:599–610.

![Administrative pathways for post-authorisation studies (PAS). Reference: BOE [Spanish Official State Gazette] No. 310, Friday 25 December 2009, Sec. I, p. 109775: Order SAS/3470/2009, of 16 December, publishing guidance on observational post-authorisation studies for medicinal products for human use. PAS-HA: post-authorisation study sponsored by the Health Authorities (HA) or funded with public funds; PAS-LA: post-authorisation study conducted at the request of the regulatory authorities and in connection with the marketing authorisation (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios or European Medicines Agency); this administrative pathway includes both studies linked to authorisation such as safety studies required by the health authorities and those included in risk management plans; PAS-OD: post-authorisation studies with designs other than prospective follow-up, e.g. cross-sectional or retrospective studies; PAS-PF: post-authorisation studies with prospective follow-up that do not correspond to any other the preceding categories; Non-PAS: studies in which the fundamental research factor under investigation is not a medicinal product; e.g. disease incidence or prevalence studies, etc. Administrative pathways for post-authorisation studies (PAS). Reference: BOE [Spanish Official State Gazette] No. 310, Friday 25 December 2009, Sec. I, p. 109775: Order SAS/3470/2009, of 16 December, publishing guidance on observational post-authorisation studies for medicinal products for human use. PAS-HA: post-authorisation study sponsored by the Health Authorities (HA) or funded with public funds; PAS-LA: post-authorisation study conducted at the request of the regulatory authorities and in connection with the marketing authorisation (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios or European Medicines Agency); this administrative pathway includes both studies linked to authorisation such as safety studies required by the health authorities and those included in risk management plans; PAS-OD: post-authorisation studies with designs other than prospective follow-up, e.g. cross-sectional or retrospective studies; PAS-PF: post-authorisation studies with prospective follow-up that do not correspond to any other the preceding categories; Non-PAS: studies in which the fundamental research factor under investigation is not a medicinal product; e.g. disease incidence or prevalence studies, etc.](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000004400000008/v2_202201010832/S244438242100167X/v2_202201010832/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)