To study the epidemiological and clinical characteristics, and response to treatmentin patients with microscopic colitis.

Patients and methodEpidemiological, clinical, blood test and endoscopic data were retrospectively collected from 113 patients with microscopic colitis. Response to treatment was analyzed in 104 of them. Efficacy and relapse after treatment with budesonide were assessed using survival curves (Kaplan-Meier).

Results78% of the patients were women, with a mean age of 65 ± 16 years. In smokers, the mean age was 10 years younger. 48% of them had some concomitant autoimmune disease; 60% suffered a single outbreak of the disease. The clinical presentation was similar in both subtypes, although patients with collagenous colitis had a chronic course more frequently (48% vs. 29%, P = .047). The remission rate with budesonide was 93% (95% CI 82–98). The cumulative incidence of relapse, after a median follow-up of 21 months, was 39% (95% CI 26%–54%): 19% at one year, 32% at two years, and 46% at three years of follow-up. There were no differences in clinical response to budesonide based on smoking habit or microscopic colitis subtype.

ConclusionsMicroscopic colitis is more frequent in elderly women. Smoking was associated with earlier onset of the disease, although it did not influence the clinical course or response to treatment. The majority (>90%) of patients treated with budesonide achieved remission, although nearly half subsequently relapsed.

Estudiar las características epidemiológicas, clínicas y la respuesta al tratamiento en pacientes con colitis microscópica.

Pacientes y métodoSe recopilaron retrospectivamente los datos epidemiológicos, clínicos, analíticos y endoscópicos de 113 pacientes con colitis microscópica. La respuesta al tratamiento se analizó en 104 de ellos. La eficacia y la recidiva tras la administración de budesonida se evaluaron mediante curvas de supervivencia (Kaplan-Meier).

ResultadosEl 78% de los pacientes fueron mujeres, con una edad media de 65 ± 16 años. En los fumadores, la edad media fue 10 años menor. Un 48% tenía alguna enfermedad inmunomediada concomitante. El 60% sufrió un único brote de la enfermedad. La presentación clínica fue similar en ambos subtipos, aunque los pacientes con colitis colágena tuvieron un curso crónico con más frecuencia (48 vs. 29%, P = ,047). La tasa de remisión con budesonida fue del 93% (IC95% = 82–98). La incidencia acumulada de recidiva, tras una mediana de seguimiento de 21 meses, fue del 39% (IC95% = 26%–54%): 19% al año, 32% a los 2 años y 46% a los 3 años de seguimiento. No hubo diferencias en la respuesta clínica a la budesonida en función del tabaquismo o el subtipo de colitis microscópica.

ConclusionesLa colitis microscópica es más frecuente en mujeres de edad avanzada. El tabaco se asoció a una aparición más precoz de la enfermedad, aunque no influyó en la evolución clínica o en la respuesta al tratamiento. La mayoría (>90%) de los pacientes tratados con budesonida alcanzaron la remisión, aunque casi la mitad recidivaron posteriormente.

Microscopic colitis (MC) is an inflammatory bowel disease characterised by the presence of chronic watery diarrhoea, a normal endoscopic appearance of the colonic mucosa, and inflammatory changes in the histological study that enable its diagnosis. MC encompasses two histological subtypes: collagenous colitis (CC) and lymphocytic colitis (LC). Both subtypes share a similar clinical presentation and response to treatment.1

Despite having been described for more than 30 years, MC is an underdiagnosed condition in our setting. In recent years, its incidence has been increasing to the point that it is currently one of the most frequent causes of chronic watery diarrhoea.2 Recent studies indicate that its incidence is, today, similar to that of Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis.3,4 Despite this, its aetiology and pathogenesis are still unknown. There are few studies that have evaluated risk factors at the population level. The disease typically affects the elderly and women, although the reason for this association is unknown.5 It has been suggested that the consumption of certain drugs could precipitate the appearance of this pathology. However, this association is contested, and a causal relationship has not been established in most studies. Nor has it been possible to identify an association between MC and the intake of any specific dietary component.6

Budesonide is the treatment of choice to induce and maintain remission in patients with MC, although the recurrence rate after it is suspended is high.7 Some patients may benefit from maintenance treatment with budesonide, although the optimal duration of the treatment or when to suspend it is unknown. Likewise, other drugs (mesalazine, loperamide, resin cholestyramine, etc.) continue to be used frequently in clinical practice, without solid evidence to support their use and with variable clinical efficacy.

Better knowledge of the clinical behaviour of this disease is crucial, due to its high prevalence and the great impact it has on the quality of life of patients.8 The objective of this study was to determine the epidemiological factors associated with the onset of MC, its clinical, analytical and endoscopic characteristics, and to evaluate the short- and long-term efficacy of the different treatments used in clinical practice for the control of the disease.

Patients and methodAn observational and retrospective study was conducted, which included all consecutive patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with CC or LC attended at the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa [La Princesa University Hospital] from 1 January 2010 until 30 June 2018.

The following variables were collected: type of MC, date and age at diagnosis, gender, smoking habit, previous surgeries, family history, symptoms, clinical course, concomitant medication and medical comorbidities. Endoscopic and laboratory data from tests performed within the month before or after diagnosis of the disease were also collected. The date of diagnosis was defined as the date on which colonoscopy with biopsy was performed. Response to treatment was evaluated in 104 of the 113 patients included, as nine of them dropped out of hospital follow-up. The clinical response achieved with the different treatments (clinical remission, partial or no response), the rate of side effects and the number of episodes of the disease were also recorded.

Definitions- •

Disease activity: three or more stools daily or at least one liquid stool daily for one week.8

- •

Clinical remission: less than three daily stools and less than one liquid stool daily.8

- •

Recurrence: once remission is reached, the reappearance of three or more daily stools or at least one liquid stool daily for at least one week.

- •

Intermittent chronic course: two or more episodes of clinical activity, with a minimum time of six months between each episode.

- •

Continuous chronic course: persistence of clinical activity for at least six months.

- •

Single episode: patients who after a first episode remained in clinical remission during follow-up.

The study protocol was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario de La Princesa and written informed consent was obtained from the patients.

Statistical studyThe results are expressed as percentages and as mean ± standard deviation or median (and interquartile range [IQR]) for variables of normal and non-normal distribution, respectively. Qualitative variables were compared using the χ2 test and quantitative variables using Student's t test or the Mann-Whitney test in those that did not follow a normal distribution.

A binary logistic regression study was performed to identify predictors of clinical recurrence. In patients receiving budesonide, efficacy and loss of response to budesonide were assessed using a Kaplan-Meier analysis, and the log-rank test was used to compare the different survival curves. In patients who achieved remission with budesonide, a multivariate analysis was performed using Cox regression to identify risk factors for clinical recurrence. The results are expressed as a hazard ratio (HR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

ResultsEpidemiological characteristicsA total of 113 patients diagnosed with MC were included (median follow-up of 23 months, IQR 10–39): 88 women (78%) and 25 men (22%), with a male-female ratio of 3.5:1. Of these, 57% had CC (64 patients), 40% had LC (45 patients) and 3% had incomplete colitis (four patients). The mean age at diagnosis was 65 ± 16 years, with no differences between men and women. Sixty-nine patients (61%) were over 65 years old at diagnosis, 32 patients (28%) were between 40 and 65 years old, and 12 patients (11%) were under 40 years old.

Fifty patients (44%) had a history of smoking (25% active smokers and 19% ex-smokers). In smokers, the mean age at diagnosis was a decade younger than in non-smokers (58 ± 13 years and 68 ± 17 years, respectively; P = .002).

Up to 48% of the patients were diagnosed with at least one immune-mediated disease. The most frequent comorbidities were: thyroid disease (19%), asthma (10%), type I diabetes mellitus (5%), coeliac disease (4%) and rheumatoid arthritis (4%).

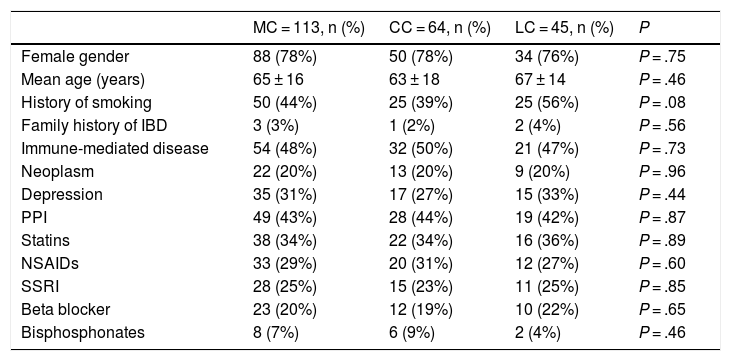

The univariate analysis showed no significant differences between patients with CC and LC in relation to gender, mean age, family history, smoking history, and frequency of medical comorbidities or of drug use (Table 1).

Comparison between the epidemiological characteristics of collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis.

| MC = 113, n (%) | CC = 64, n (%) | LC = 45, n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female gender | 88 (78%) | 50 (78%) | 34 (76%) | P = .75 |

| Mean age (years) | 65 ± 16 | 63 ± 18 | 67 ± 14 | P = .46 |

| History of smoking | 50 (44%) | 25 (39%) | 25 (56%) | P = .08 |

| Family history of IBD | 3 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (4%) | P = .56 |

| Immune-mediated disease | 54 (48%) | 32 (50%) | 21 (47%) | P = .73 |

| Neoplasm | 22 (20%) | 13 (20%) | 9 (20%) | P = .96 |

| Depression | 35 (31%) | 17 (27%) | 15 (33%) | P = .44 |

| PPI | 49 (43%) | 28 (44%) | 19 (42%) | P = .87 |

| Statins | 38 (34%) | 22 (34%) | 16 (36%) | P = .89 |

| NSAIDs | 33 (29%) | 20 (31%) | 12 (27%) | P = .60 |

| SSRI | 28 (25%) | 15 (23%) | 11 (25%) | P = .85 |

| Beta blocker | 23 (20%) | 12 (19%) | 10 (22%) | P = .65 |

| Bisphosphonates | 8 (7%) | 6 (9%) | 2 (4%) | P = .46 |

CC: collagenous colitis; CL: lymphocytic colitis; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; MC: microscopic colitis; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PPI: proton pump inhibitor; SSRI: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

The median time to diagnosis was four months (IQR 2–7), with no differences by gender. In patients with CC, the time to diagnosis was longer than in patients with LC: median of five months (IQR 2–11) vs. three months (IQR 2–6) (P = .02).

The most frequent symptoms at the onset of MC were diarrhoea (98%), weight loss (43%) and abdominal pain (31%). Fourteen per cent of the patients presented fatigue or faecal urgency. Other less frequent symptoms were: nocturnal diarrhoea (12%), incontinence (11%), rectal bleeding (8%) and meteorism (7%). There were no relevant differences between CC and LC in relation to the form of presentation of MC.

Of the patients with MC, 60% had a single episode of the disease, 31% an intermittent clinical course, and 9% a continuous chronic course. Patients with LC had a single episode more frequently than CC patients, and the difference was statistically significant (71% vs. 52%; P = .047). In patients with CC, the disease progressed to chronic forms more frequently than in patients with LC (continuous chronic course 14% vs. 2%, and intermittent chronic course 35% vs. 26%; P = .047). There were no differences in the clinical course of the disease between patients with or without tobacco exposure (continuous or intermittent chronic course 44% vs. 36%, P = .4).

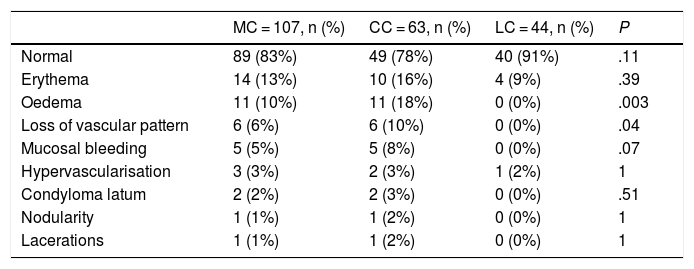

Colonoscopy findingsColonoscopy showed changes in the colonic mucosa in 16% of the patients. Table 2 shows the main findings in the diagnosis of MC in patients with CC and LC. In 12% of the colonoscopies, biopsies were taken by sections, as recommended by the Grupo Español de Colitis Microscópica [Spanish Microscopic Colitis Group]. In 39% of the colonoscopies, biopsies were taken from the right, transverse and left colon, and in 49%, biopsies were taken only from the right and the left colon. Biopsies of the right colon showed changes compatible with the diagnosis of MC in 98% of cases, those of the transverse colon in 100%, those of the descending colon in 97%, those of the sigmoid in 93%, and those of the rectum in 84% of the cases.

Comparison between the main findings in the colonic mucosa of patients with collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis.

| MC = 107, n (%) | CC = 63, n (%) | LC = 44, n (%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 89 (83%) | 49 (78%) | 40 (91%) | .11 |

| Erythema | 14 (13%) | 10 (16%) | 4 (9%) | .39 |

| Oedema | 11 (10%) | 11 (18%) | 0 (0%) | .003 |

| Loss of vascular pattern | 6 (6%) | 6 (10%) | 0 (0%) | .04 |

| Mucosal bleeding | 5 (5%) | 5 (8%) | 0 (0%) | .07 |

| Hypervascularisation | 3 (3%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (2%) | 1 |

| Condyloma latum | 2 (2%) | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | .51 |

| Nodularity | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

| Lacerations | 1 (1%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 |

CC: collagenous colitis; LC: lymphocytic colitis; MC: microscopic colitis.

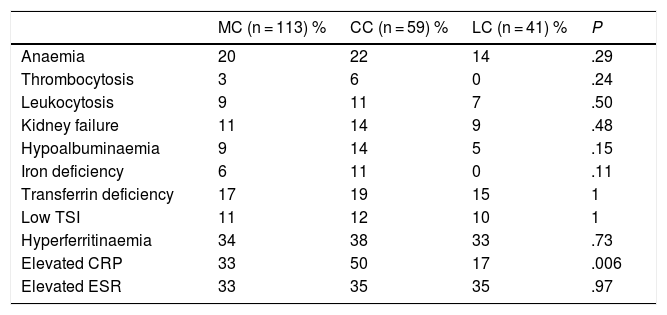

Patients with CC presented greater analytical alterations than patients with LC, although only the elevated level of C-reactive protein was statistically significant. Table 3 lists the differences between the analytical parameters in patients with CC and LC.

Comparison between the laboratory characteristics of patients with microscopic colitis, collagenous colitis and lymphocytic colitis.

| MC (n = 113) % | CC (n = 59) % | LC (n = 41) % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaemia | 20 | 22 | 14 | .29 |

| Thrombocytosis | 3 | 6 | 0 | .24 |

| Leukocytosis | 9 | 11 | 7 | .50 |

| Kidney failure | 11 | 14 | 9 | .48 |

| Hypoalbuminaemia | 9 | 14 | 5 | .15 |

| Iron deficiency | 6 | 11 | 0 | .11 |

| Transferrin deficiency | 17 | 19 | 15 | 1 |

| Low TSI | 11 | 12 | 10 | 1 |

| Hyperferritinaemia | 34 | 38 | 33 | .73 |

| Elevated CRP | 33 | 50 | 17 | .006 |

| Elevated ESR | 33 | 35 | 35 | .97 |

CC: collagenous colitis; LC: lymphocytic colitis; MC: microscopic colitis.

Anaemia: haemoglobin values <13 g/dl in men and <12 g/dl in women.

Normal values: platelets 150–450,000/mm3; leukocytes 4–10,000/mm3; creatinine 0.7–1.2 mg/dl; albumin 3.5–5.2 g/dl; iron 33–193 ug/dl; transferrin 200−360 mg/dl; TSI (transferrin saturation index) 15%–50%; ferritin 15−150 ng/dl; CRP (C-reactive protein) 0.00−0.50 mg/dl; ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) 0–25.

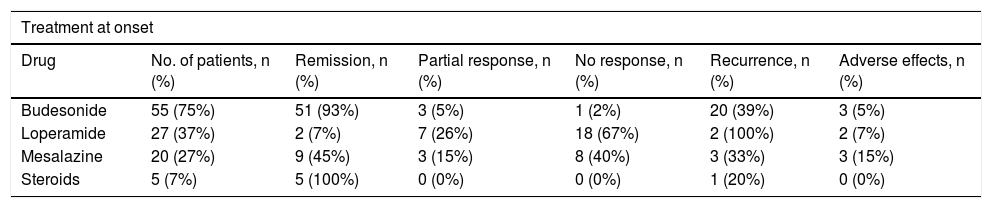

Response to treatment was evaluated in 104 patients. Thirty per cent (31 patients) achieved clinical remission spontaneously at the onset of the disease: 29% of patients with CC and 31% of patients with LC. Of those who did not achieve remission spontaneously, 55 patients (75%) received budesonide treatment, 27 (37%) received loperamide, 20 (27%) received aminosalicylates, and five (7%) received systemic corticosteroids. Of the patients treated with budesonide, 29 received budesonide as first-line treatment and 26 received it as second-line treatment (18 patients after failure of loperamide and eight patients after failure of mesalazine). Remission rates were 93% with budesonide, 7% with loperamide, 45% with aminosalicylates and 100% with systemic corticosteroids (60% developed corticodependence).

Table 4 shows the clinical response achieved with the different treatments received after the onset of MC, and the rate of adverse effects with each treatment. The adverse effects were mostly mild, but required suspension of the drug in all cases. The adverse effects recorded under budesonide treatment were steroid myopathy, glaucoma and constipation. Two patients treated with mesalazine experienced a worsening of diarrhoea and another patient had a transaminase alteration. Of the patients treated with loperamide, two developed adverse effects (constipation and an urticarial reaction, respectively).

Comparison between the efficacy and adverse effects of the different treatments received at the onset of microscopic colitis.

| Treatment at onset | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug | No. of patients, n (%) | Remission, n (%) | Partial response, n (%) | No response, n (%) | Recurrence, n (%) | Adverse effects, n (%) |

| Budesonide | 55 (75%) | 51 (93%) | 3 (5%) | 1 (2%) | 20 (39%) | 3 (5%) |

| Loperamide | 27 (37%) | 2 (7%) | 7 (26%) | 18 (67%) | 2 (100%) | 2 (7%) |

| Mesalazine | 20 (27%) | 9 (45%) | 3 (15%) | 8 (40%) | 3 (33%) | 3 (15%) |

| Steroids | 5 (7%) | 5 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (20%) | 0 (0%) |

Of the 104 patients analysed, 35 (34%) had a first recurrence of the disease after reaching remission, and 11 (11%) had a second recurrence. The clinical recurrence rate was 35% in patients with CC and 31% in patients with LC. Gender, age at diagnosis (older or younger than 50 years), history of smoking, or the presence of immune-mediated diseases were not associated with an increased risk of recurrence. Patients who achieved clinical remission with drug treatment relapsed more frequently than those who achieved remission spontaneously (38% vs. 23%), although this difference was not significant (P = .11).

Analysis of the response to budesonideA total of 55 patients (75%) received budesonide treatment at the onset of the disease (28 patients with CC and 27 with LC). Almost half of the patients (49%) received a budesonide regimen of 9 mg for one month, followed by 6 mg for one month and 3 mg for another month. The rest of the patients (51%) received other regimens with variable doses of 6−9 mg for 8–12 weeks. Of the patients treated with budesonide, 93% (CI 95% 82–98) achieved remission, 5% had a partial response and 2% did not respond to treatment. There was no difference in the clinical remission rate between patients with CC and with LC (93% in both).

Of the patients treated with budesonide at the onset of the disease, 18% required maintenance treatment due to the impossibility of suspending the drug. Of these, half required daily doses of 3 mg to maintain remission, 40% required 6 mg and 10% doses of 9 mg. Patients with CC started maintenance treatment more frequently than patients with LC (29% vs. 7%), although this difference was not significant (P = .078 ).

Of the patients who achieved remission with budesonide at the onset of CM, 39% had a first recurrence. The median time to recurrence was 14 months (IQR 5–31). Of the patients who relapsed, 95% responded again to budesonide, 36% receiving 9 mg for one month, followed by 6 mg for another month and 3 mg for a last month. The rest of the patients (64%) received other regimens with variable doses of 6−9 mg for 8–12 weeks. Twelve patients (48%) started maintenance treatment: 75% required a dose of 3 mg to maintain remission, 17% required 6 mg and 8% 9 mg.

Five patients had a second relapse, resolved in all cases after restarting budesonide. All required maintenance treatment, half at a daily dose of 3 mg and the other half at a dose of 6 mg.

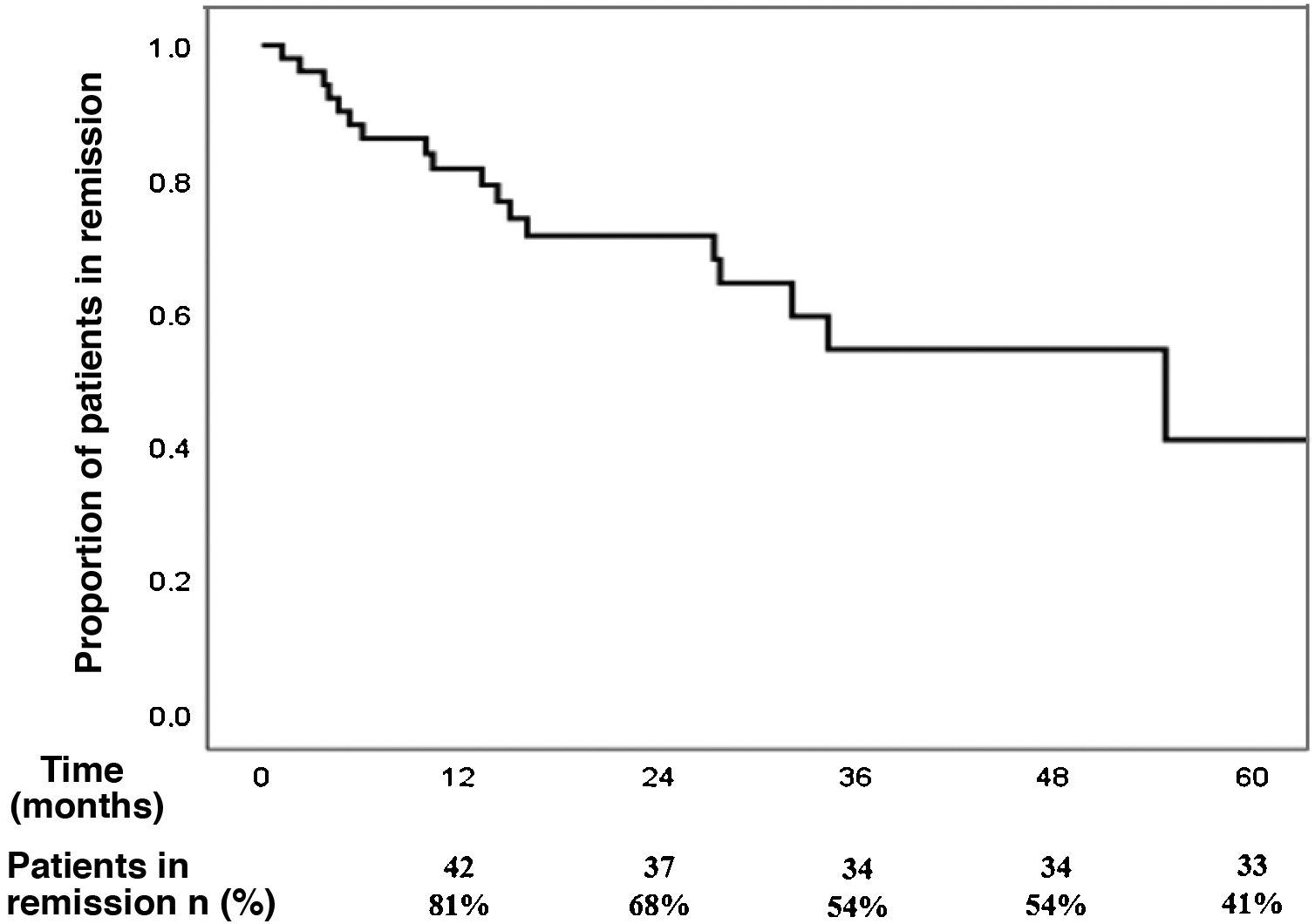

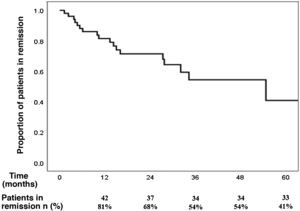

The cumulative incidence of recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide at the onset of the disease, after a median follow-up of 21 months (IQR 9–32), was 39% (95% CI 26%–54%): 19% at one year, 32% at two years and 46% at three years of follow-up (Fig. 1). The incidence rate of recurrence was 17% per patient-year of follow-up.

None of the variables analysed (gender, age, smoking history, immune-mediated diseases, or initiation of maintenance treatment) in the multivariate analysis was associated with a higher risk of clinical recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide. Patients who started maintenance treatment with budesonide after reaching remission had a lower probability of clinical recurrence (29% vs. 41%; HR 0.03; CI 95% 0.01–5.9) although this difference again was not statistically significant (P = .19).

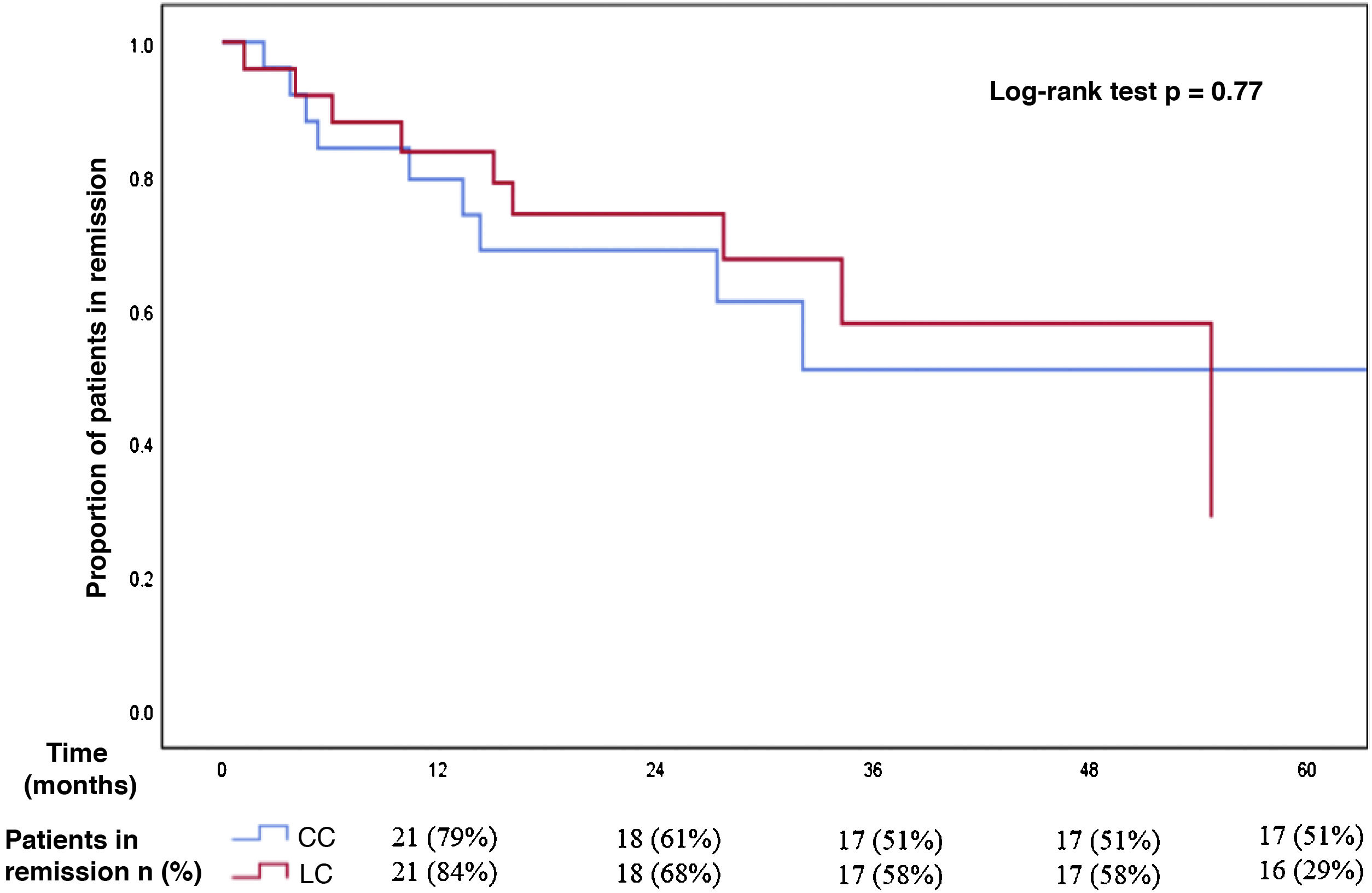

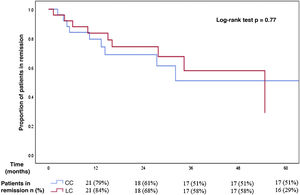

Regarding the MC subtype, the cumulative incidence of recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide in patients with CC (median follow-up of 14 months, IQR 7–32) was 42% (CI 95% 23–63): 21% at one year, 39% at two years and 49% at three years of follow-up. The median time to recurrence was 13 months (IQR 5–32). For patients with LC, the cumulative incidence of recurrence after a median follow-up of 24 months (IQR 11–35) was 36% (CI 95% 18–57): 16% at one year, 32% at two years and 42% at three years of follow-up. The median time to recurrence was 15 months (IQR 5–31). There was no significant difference in the incidence of recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide in patients with CC and with LC (Fig. 2).

Comparison between recurrence-free time in patients with collagenous and lymphocytic colitis who initially achieved clinical remission with budesonide.

There were no significant differences between both subgroups in the incidence of recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide (cumulative incidence of relapse of 42% in patients with collagenous colitis and 36% in patients with lymphocytic colitis).

Previous studies have shown an increase in the incidence of MC with age, although the reason for this association remains unknown.9,10 In our sample, 61% of patients were over 65 years of age at the time of diagnosis and only 11% were under 40. This could be due to a real increase in the incidence with age, or to a greater diagnosis of the disease given the greater number of endoscopic examinations performed in this age group. The higher frequency of polypharmacy in elderly subjects could also explain this distribution of the disease. Although MC predominates in elderly subjects, it is not exclusive to this age group and, in fact, several authors have suggested there has been an increase in the incidence of MC in young subjects in recent decades.3,11 A recent study carried out in France in 130 patients with MC showed a mean age of 45 years, with an incidence of 6/100,000 inhabitants among patients between 40 and 49 years of age.4 In other series, up to 25% of patients with MC were under 40 years of age.12 All of this requires maintaining a high index of suspicion and ruling out this disease in all patients with chronic diarrhoea, regardless of their age.

Traditionally, a clear predominance of MC in women has been reported, with an incidence in women 2–8 times higher than in men,10,12 which is consistent with our results. Some authors have suggested that this predilection for the female gender is more pronounced in the CC subtype.4,9 Hormonal factors could be involved in collagen metabolism, while others put the female predominance down to an autoimmune pathogenic mechanism, more commonly found in women. In our study, we did not find significant differences between men and women regarding the frequency of LC or CC, or of immune-mediated diseases.

Previous publications have shown that smoking is associated with a higher risk and earlier onset of MC.13,14 In our study, the disease appeared up to 10 years earlier in smokers than in non-smokers, matching previous descriptions.15 Although several hypotheses have been suggested (alterations in microvascularisation, reduced vascular flow, etc.),16 the effects of smoking on MC have not yet been clearly explained. In a previous study, Fernández-Bañares et al. found no differences between smokers and non-smokers in relation to the clinical presentation of MC or its remission rate,15 which agrees with our results. Tobacco seems to be associated with a higher risk of onset of the disease, but without a clear influence on its subsequent clinical course or response to treatment.

The list of potentially MC-inducing drugs is growing. In a recent French study, 50% of patients with MC had started one or more new drugs in the three months prior to the onset of diarrhoea, and several of these patients clinically improved after stopping these treatments.17 However, in this study, as in the majority that have evaluated the role of drugs in MC, it was not possible to demonstrate a clear causality (as re-exposure to the drug had been avoided), so the improvement after its withdrawal could simply be due to a spontaneous remission of MC. A recent meta-analysis of retrospective studies concludes that the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and statins is associated with a slightly increased risk of developing MC, while the use of proton pump inhibitors and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is associated with a much higher risk.18 In our study, almost half of the patients received proton pump inhibitors, a third statins, and 29% non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Up to 16% of our cohort had macroscopic (endoscopic) lesions in the colonic mucosa. Other series have described findings such as erythema, oedema, mucosal lacerations or changes in vascular pattern with frequencies of up to 33%.4 These endoscopic findings are nonspecific and their actual prevalence is unknown, although they are being described with increasing frequency in patients with MC and especially in patients with CC.19 We found a higher frequency of these lesions in patients with CC, although only the presence of oedema and the loss of vascular pattern reached statistical significance. It should be noted that only in 12% of the colonoscopies were biopsies taken by sections, despite this being recommended by the Spanish Microscopic Colitis Group, which reflects the low awareness of this disease among gastroenterologists.

Budesonide was the most frequently prescribed drug (75%), obtaining a clinical remission rate of 93%, similar to the results of published clinical trials. The recurrence rate observed after reaching remission (39%) was also similar to that previously described in observational studies, although lower than that reported in clinical trials.7 In the multivariate analysis, none of the variables analysed was associated with an increased risk of clinical recurrence after reaching remission with budesonide.

Previous studies have confirmed that being under 60 years of age is an independent risk factor for recurrence, once remission with budesonide is achieved.20 Fernández-Bañares et al. also found a risk of clinical recurrence three times higher in patients with CC less than 50 years old.15 In our study, patients under 50 years of age had a greater likelihood of recurrence than older patients (50% vs. 37%), although this difference did not reach statistical significance, perhaps due to a sample size problem.

Some authors suggest that the clinical course of LC differs from that of CC, with a higher rate of spontaneous remission21 and a greater response to placebo in the former.22 In any case, this possibility continues to be contested. The data from the present study show that the rate of spontaneous remission, of response to budesonide and the frequency of prolonged remission of the disease in CC and CL are very similar. However, patients with CC present chronic forms and require long-term maintenance drug therapy more frequently than those with LC.23

Despite the good initial response to budesonide, almost half of patients have relapses after its suspension throughout the follow-up period (cumulative incidence of 46% at three years). This makes low-dose maintenance treatment a good option in these patients.24 A recent study by the Spanish Microscopic Colitis Group demonstrated that low doses of budesonide (3 mg daily or every other day) were useful to maintain long-term clinical remission in around 80% of patients.25 In our study, the majority of patients who required maintenance treatment maintained remission with a dose of 3 mg daily, and less than 10% required 9 mg daily. It is currently unclear which patients might benefit from maintenance therapy or when to start it. However, given the good response to low doses of budesonide, in patients with two or more relapses it seems reasonable to initiate long-term maintenance treatment at the lowest effective dose (3 mg daily or every few days, although this has not been tested in clinical trials).

Our study has several limitations. First, the small sample size may have led to an increase in type II error. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, adherence to treatment could not be monitored, which may have conditioned the rates of remission and relapse observed, although these are similar to those obtained in previous studies. The total duration of maintenance treatment with budesonide could not be recorded, since the majority of patients maintained this at the end of the study follow-up period. Therefore, no firm recommendation can be made on the optimal duration of maintenance treatment or when to suspend it without risk of relapse. Likewise, the existence of other conditions that may be related to MC (such as coeliac disease) was not routinely ruled out in all cases, so its prevalence may be underestimated. However, it is one of the studies with the largest number of patients evaluating the epidemiology, clinical behaviour, and response to MC treatment carried out in our country.

In conclusion, MC should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with chronic watery diarrhoea, especially in elderly women or those with immune-mediated diseases. Diarrhoea, weight loss and abdominal pain are the most common symptoms. Smoking was associated with earlier onset of the disease, although it did not influence the clinical course or response to treatment. The vast majority of patients respond to budesonide treatment, although the recurrence rate is high (40%). Both subtypes of MC had a similar clinical presentation and response to budesonide, although the disease was more frequently chronic in patients with CC.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestJ.P. Gisbert has provided scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities for: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Vifor Pharma.

María José Casanova has provided support for research and/or training activities for: Pfizer, Janssen, MSD, Takeda, Ferring, Faes Farma, Norgine, Dr. Falk Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Abbvie.

Eukene Rojo declares that he has no conflicts of interest in relation to this article.

Please cite this article as: Rojo E, Casanova MJ, Gisbert JP. Características epidemiológicas, clínicas y respuesta al tratamiento en 113 pacientes con colitis microscópica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:671–679.