Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic bowel disease with an intermittent course characterised by continuous inflammation of the mucosa which, to varying extents, affects the rectum and the rest of the colon. Although there is a broad range of therapies available, it is not possible to keep the inflammatory activity in remission in some patients. Anti-TNFα drugs are one of the most effective and widely used treatments in cases of moderate/severe activity. Opportunistic infections are one of the main side effects of this therapy. Another less common adverse effect is the development of demyelinating disease due to nervous system involvement.1–3

With this in mind, we present the case of a 56-year-old female patient, diagnosed with pan-ulcerative colitis at the age of 44 after presenting with a severe steroid-refractory flare-up which required rescue ciclosporin and 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP) for maintenance. A few months later, she had a further severe flare-up, requiring infliximab (anti-TNFα)) 5mg/kg weeks 0, 2 and 6, with subsequent escalation to 5mg/kg every four weeks due to severe endoscopic activity. After one year of treatment with clinical remission the infliximab was discontinued, maintaining 6-MP, but this was then stopped due to recurrent urinary tract infections and leukopenia. For the next four years she was treated with oral mesalazine 2g/day, with a good response. The infliximab then had to be restarted at 5mg/kg in weeks 0, 2 and 6, due to moderate-to-severe clinical exacerbation. However, after the induction, she had a severe infusion reaction to infliximab, and was switched to adalimumab (anti-TNFα) 40mg SC every two weeks for maintenance. This did not achieve an adequate clinical response, despite adding granulocytapheresis and tacrolimus suppositories.

In the absence of response, the patient was started on vedolizumab (anti-integrin α4β7) 300mg IV every eight weeks, with subsequent escalation to every four weeks. However, her UC remained chronically active with elevated levels of faecal calprotectin. Surgical treatment was then considered, but after being rejected by the patient, it was decided to start golimumab (anti-TNFα) 200/100mg weeks 0 and 2, escalating to 100mg SC every two weeks for maintenance due to partial response after the induction.

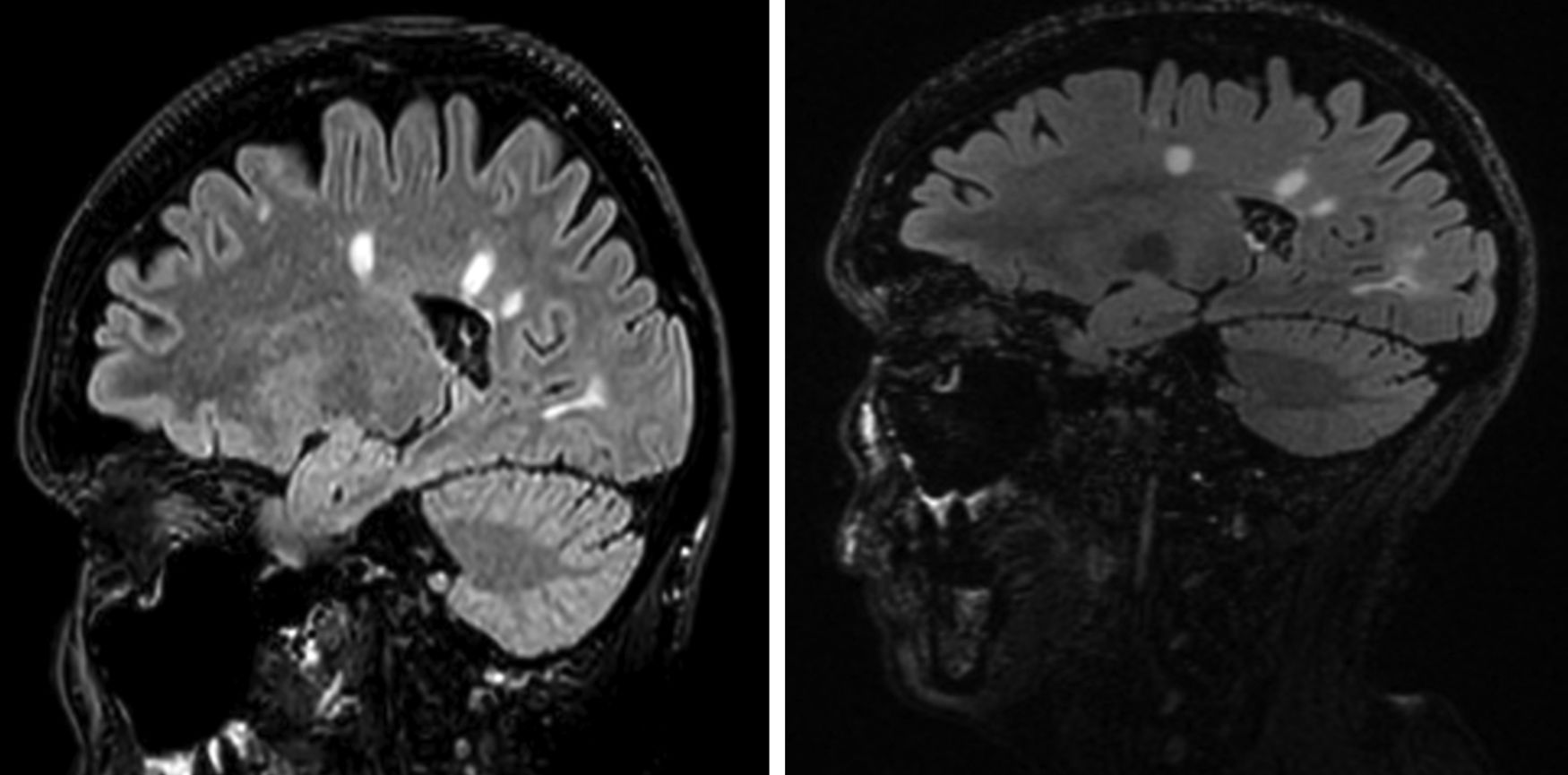

Nine months after starting the treatment, the patient developed dysaesthesia in her lower limbs. Brain MRI revealed lesions with a demyelinating profile, typical of multiple sclerosis (MS), in the corpus callosum and periventricular and juxtacortical areas. The differential diagnosis was between multiple sclerosis (MS), neuromyelitis optica and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. The diagnosis of MS was established due to the presence of intrathecal oligoclonal bands (a finding seen in 80% of MS) and the typical brain lesions of this disease.

As golimumab was the only treatment the patient was taking, in view of the reported association between anti-TNFα and MS,1–3 the trigger for the MS was assumed to be golimumab. This adverse event was unrelated to the dose used.

As the patient was found to be positive for anti-John Cunningham virus antibodies, natalizumab was not administered, but she was given oral fingolimod (S1P receptor modulator) 0.5mg/day and boluses of 6-methylprednisolone 1g per day orally for three days, with excellent response. The follow-up MRI one year after diagnosis (Fig. 1) showed the demyelinating lesions to be stable.

Interestingly, from the point of view of her UC, after failure of various different lines of medical treatment, 12 weeks after starting fingolimod the patient had a complete clinical and endoscopic response. She has now been on fingolimod for over three years.

The pathogenesis of MS with anti-TNFα therapy is still not fully understood.1,3 New drugs are emerging for UC, including S1P receptor modulator drugs (fingolimod, approved for MS and ozanimod, second generation).4,5 The blockade of the S1P receptor leads to the sequestration of lymphocytes in the peripheral lymphoid organs, which hinders their transit to the areas of inflammation. These drugs could be effective in the management of UC and MS. Although this is an anecdotal case of strong response to fingolimod, this family of drugs could be an option for compassionate use in patients with chronic activity refractory to current pharmacological treatments, whose only option is surgery.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Ladrón Abia P, Alcalá Vicente C, Martínez Delgado S, Bastida Paz G. Remisión inducida por fingolimod en una paciente con colitis ulcerosa y esclerosis múltiple. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:156–157.