Gastric cancer (GC) incidence is currently decreasing; however, survival is still low. Early GC (EGC) has better prognosis and it could be cured by endoscopic methods.

Patients and methodsObservational study of a retrospective cohort of all patients with GC during a five-year period in a health area of Spain. EGC diagnosis was defined as mucosal or submucosal (T1) cancers regardless of lymph node involvement, whereas the advanced GC was T2–T4.

Results209 patients were included, and 26 (12%) of them were EGC. There was no difference between EGC and advanced GC in age, sex, HP infection, precancerous lesions or histological type. Other characteristics of EGC were different from advanced GC: location (antrum and incisura in 76% vs. 38%, p=0.01), alarm symptoms (69% vs. 90%, p<0.01), curative treatment (100% vs. 30%, p<0.01), performance status (PS 0–1: 92% vs. 75%, p=0.03) and survival (85% vs. 20%, p<0.001). Among patients who received curative treatment, 98% (79/81) underwent surgery and 2% (2/81) were treated by mucosectomy. Seven (27%) patients with EGC could have benefited from treatment by endoscopic submucosal resection.

DiscussionEGC frequency was low (12% of GCs) in our health area. EGC had a high percentage of alarm symptoms, and was located in the distal third of the stomach (antrum and incisura) and had better prognosis compared to advanced GC. Strategies to increase detection and endoscopic treatment of EGC should be implemented.

En la actualidad, la incidencia del cáncer gástrico (CG) está disminuyendo, sin embargo, la supervivencia continúa siendo baja. El cáncer gástrico precoz (CGP) ofrece un mejor pronóstico y la posibilidad de tratamientos endoscópicos curativos.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio observacional de una cohorte retrospectiva de todos los pacientes con CG en un periodo de 5años en un área sanitaria de España. El CGP incluyó los pacientes con afectación mucosa o submucosa (T1) independientemente de la afectación ganglionar, mientras que el avanzado fueron los T2-T4.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 209 pacientes de los cuales 26 (12%) fueron CGP. El CGP no tuvo diferencias en comparación con el avanzado en la edad, sexo, infección por HP, lesiones premalignas ni tipo histológico; sin embargo, tuvo diferencias significativas en la localización (antro e incisura en un 76% vs. 38%, p=0,01), síntomas de alarma (69% vs. 90%, p<0,01), tratamiento con intención curativa (100% vs. 30%, p<0,01), performance status (PS 0-1: 92% vs. 75%, p=0,03) y supervivencia (85% vs. 20%, p<0,001). Entre los pacientes tratados con intención curativa, el 98% (79/81) fueron operados y el 2% (2/81) fueron tratados con mucosectomía. Siete (27%) pacientes con CGP se hubiesen podido beneficiar de disección submucosa.

DiscusiónLa frecuencia del CGP fue baja en nuestra área sanitaria (12% de los CG). El CGP tuvo síntomas de alarma en un alto porcentaje, se localizó en el tercio distal del estómago (antro e incisura) y tuvo mejor pronóstico en relación con el CG avanzado. Se deben implementar medidas para incrementar la detección y tratamiento endoscópico del CGP.

The incidence of gastric cancer (GC) is decreasing all over the world, although it remains the fifth leading type of cancer in terms of incidence and the third most fatal.1 The reduction in the incidence of GC is due to the implementation of primary prevention strategies, such as better food preservation and eradication of Helicobacter pylori (HP).1,2 Despite this improvement, 5-year survival in patients diagnosed with GC is remains low (less than 30%), mainly because it is diagnosed in advanced stages.3

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) is the diagnostic method of choice because it enables identification and biopsy of lesions.4 Clinical practice guidelines recommend an OGD in the presence of dyspepsia in all patients older than 55–60 years, or younger in the following cases: (a) recurrence of symptoms, (b) presence of one or more warning symptoms (weight loss, vomiting, dysphagia, odynophagia, signs of upper gastrointestinal bleeding, palpable abdominal mass, etc.), or (c) presence of high-risk factors for malignancy (being from a country with a high incidence or a family history of GC).4,5 Once GC is diagnosed, it is clinically staged according to the TNM classification.6

Early gastric cancer (EGC) is distinguished from advanced gastric cancer (AGC) by degree of gastric wall invasion. EGC is a carcinoma confined to the mucosa (T1a) or submucosa (T1b) regardless of lymph node involvement.7 According to the TNM classification, EGC is included as a T1, whereas AGC includes T2–T4.7,8 From an endoscopic standpoint, it is possible to predict GC as EGC according to microscopic appearance, mucus pattern and vascular pattern.9 Additional tests such as endoscopic ultrasound and abdominal tomography aid in clinical differentiation between EGC and AGC.6

Identification of EGC in a OGD is important because the risk of spread to the lymph nodes is low and it is associated with a 5-year survival rate of 90% following surgery with lymph node dissection.10 Nevertheless, endoscopic treatment, which is less invasive, could be beneficial for some patients with EGC – for example, patients with clinical stage T1a adenocarcinoma that is differentiated without ulceration ≤2cm (classic criterion) or one of the following (expanded criteria): differentiated without ulceration >2cm, differentiated with ulceration ≤3cm or undifferentiated without ulceration ≤2cm.11

High-risk countries (particularly East Asian countries), in view of the importance of diagnosing EGC, are carrying out population screening programmes in asymptomatic patients12; a significant increase has been seen in the proportion of EGC in recent decades in Japan and South Korea.13 This type of strategy is not pursued in low-and intermediate-risk Western countries such as Spain due to its limited cost effectiveness.14 However, with a view to improving EGC identification, measures have been adopted for diagnosis in early stages, such as access to an OGD from primary care,15 use of high-resolution endoscopy and chromoendoscopy. In addition, more recently, European clinical practice guidelines have been developed to improve OGD quality as well as detection and endoscopic monitoring of premalignant gastric lesions.14,16 Despite these measures, an increase in the frequency of detection of EGC has not been achieved.17,18

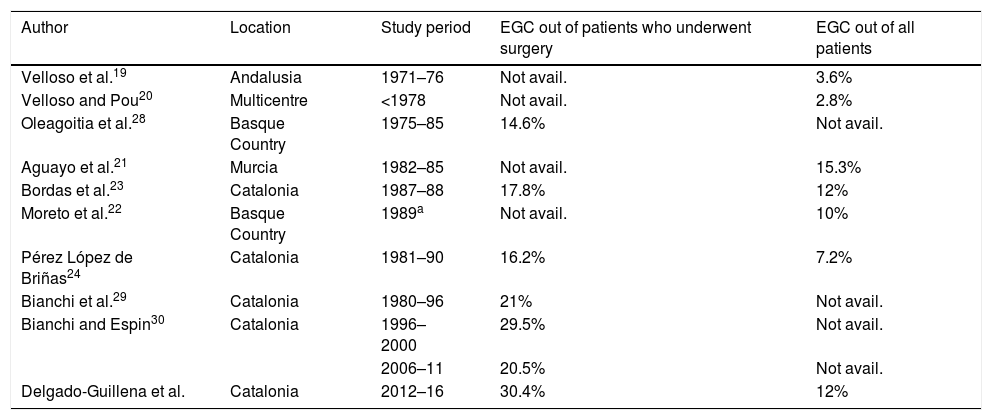

The most recent data on the frequency of EGC in the Spanish population, from the early 1990s, estimated that EGC accounted for 2.8%–15.3% of all GC diagnoses.19–24 Therefore, we set out to determine the frequency of and clinical considerations in EGC versus AGC in a healthcare area in Spain.

Patients and methodsA retrospective, observational study. All patients diagnosed with GC between January 2012 and December 2016 in the healthcare area of Vallès Oriental (Barcelona) were enrolled. This region had a mean population of 434,498 inhabitants per year in the study period (data from the Servei Català de la Salut [Catalan Health Service], CatSalud). The patients were recruited from the Pathology Unit at Hospital General de Granollers [Granollers General Hospital], where the histological studies of the 3 county hospitals in this healthcare area are centralised. The study protocol was approved by the Hospital General de Granollers ethics committee.

Information was obtained from electronic medical records. The following information was collected: demographic data (age and sex), HP infection at diagnosis, warning symptoms, histology, tumour location, TNM staging, treatment type, performance status and death (at the end of follow-up: 31 December 2017). Treatment was classified according to three categories: (i) curative intent: endoscopic resection or R0/R1 surgery; (ii) palliative: R2 surgery or chemotherapy/radiotherapy alone; and (iii) comfort: no surgery or chemotherapy/radiotherapy.25 Information was also gathered on associated premalignant lesions (atrophy, intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia) in resected specimens corresponding to GC which underwent treatment with curative intent.

GC was diagnosed using the biopsies obtained in the OGD. Staging of GC as EGC was based on involvement of mucosa and/or submucosa regardless of lymph node involvement (T0-1), whereas AGC was comprised of T2-T4 and patients whose clinical condition did not allow for staging tests.7,8 In patients having undergone surgery or endoscopy, staging was performed according to analysis of gastric specimen resected (pTNM or ypTNM for patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy), whereas initial clinical staging (cTNM) was used in patients not having undergone such a procedure. This study used the seventh edition of the TNM classification of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC).6

Finally, the characteristics of the patients with EGC and the possibility of a cure if submucosal dissection had been performed were analysed. The following curative criteria were considered in the analysis of the surgical specimen11: (i) classic curative criterion: pT1a, size ≤2cm and differentiated type; and (ii) expanded criteria:

- (a)

pT1a, size >2cm, differentiated type without ulceration;

- (b)

pT1a, size >3cm, differentiated type with ulceration;

- (c)

pT1a, size >2cm, undifferentiated type without ulceration;

- (d)

(d) pT1b (sm1, <500μm), size ≤3cm, differentiated type.

For this sub-analysis, the differentiated histological type was intestinal adenocarcinoma and the well-differentiated or moderately differentiated type, whereas the undifferentiated type was the diffuse type, poorly differentiated type or that which presented signet ring cells.11,26 EGC morphology was classified as follows: 0-I: polypoid lesion; 0-IIa: flat elevated lesion; 0-IIb: flat non-elevated lesion; 0-IIc: flat depressed lesion; 0-III: excavated lesion.7

Statistical analysisCategorical variables were presented as absolute and relative values and the chi-squared test, Fisher's exact test or the linear-by-linear association test was performed (as applicable in each case). Age was presented as a continuous variable in terms of mean (±standard deviation) or median (minimum and maximum value), normality was assessed with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and comparison was done with the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test. The Kaplan–Meier regression method was used for analysis of survival, and comparison was done with the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed with the SPSS Statistics for Windows software program, version 24.0, with a p<0.05 being considered statistically significant.

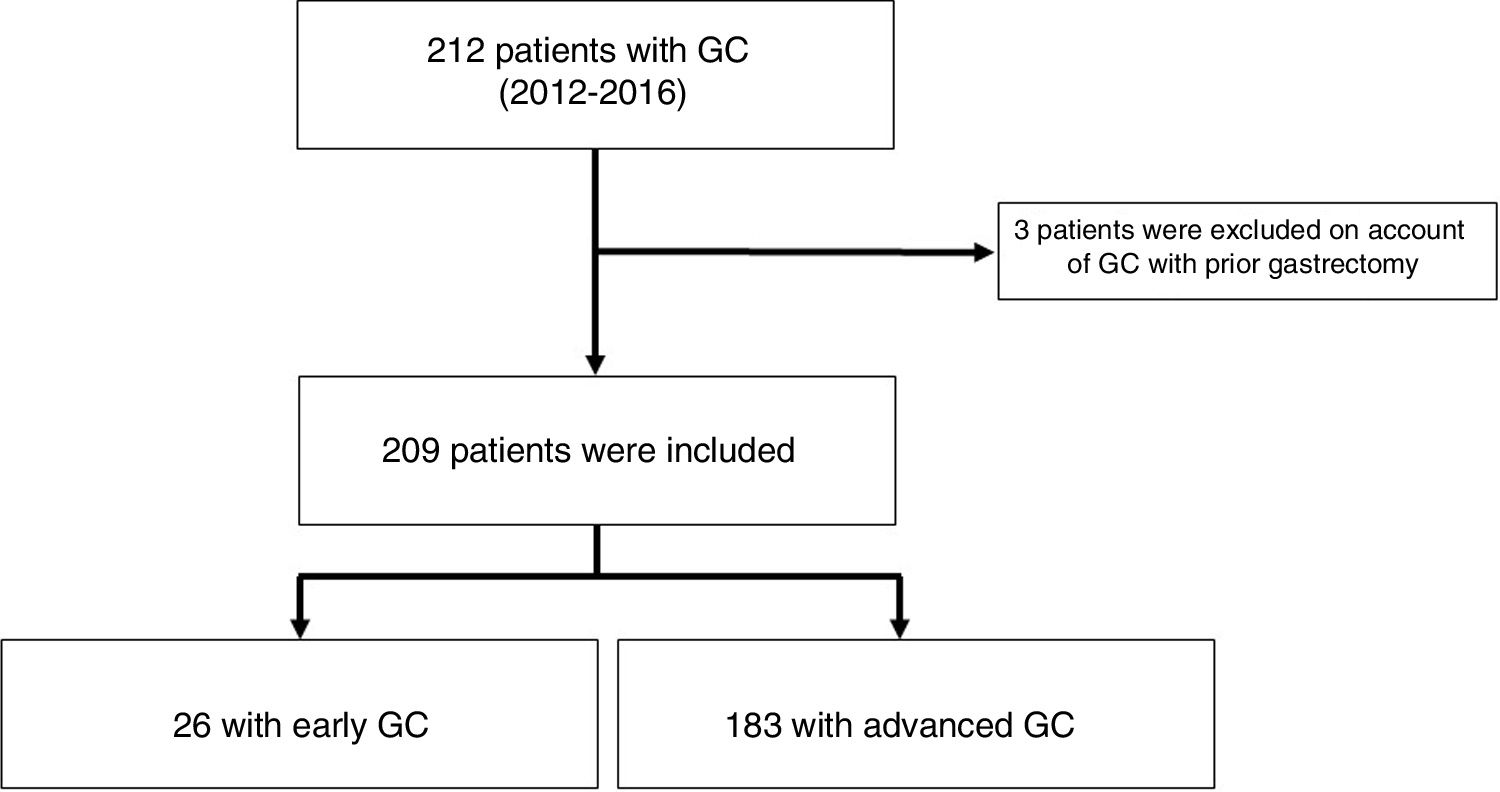

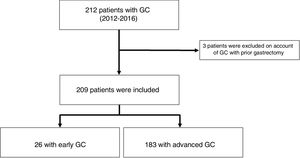

ResultsFrequencyA total of 212 cases of gastric adenocarcinomas were identified. Of these, 209 patients were included, and 3 patients were excluded because they had a history of gastrectomy for GC (we could not verify whether they had relapses, synchronic lesions or metachronic lesions). A total of 81 (38%) patients received treatment with curative intent; of them, 98% (79/81) underwent gastrectomy and 2% (2/81) underwent endoscopic treatment consisting of mucosectomy (Table 1). Out of all patients with GC, 12% (26/209) had EGC (Fig. 1) and 30.4% (24/79) underwent surgery with curative intent (Table 1). We did not identify patients with clinical staging of EGC in whom clinical follow-up had been decided; however, we did find that the GC in 38% (10/26) of the patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy and subsequent surgery with curative intent was classified as EGC (Table 2).

Characteristics of patients with early and advanced gastric cancer.

| Total | EGC | AGC | p | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | %col | n | %col | ||

| Patients (n) | 209 | 100% | 26 | 12% | 183 | 88% | |

| Mean age (SD)+Median [min–max] | 72 (12.7) | 74 [31–93] | 69 (12.4) | 72 [35–86] | 72 (12.8) | 74 [31–93] | 0.197 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Female | 87 | 42% | 10 | 39% | 77 | 42% | 0.726 |

| Male | 122 | 58% | 16 | 61% | 106 | 58% | |

| H. pylori infection | |||||||

| Negative | 196 | 94% | 23 | 89% | 173 | 95% | 0.209 |

| Positive | 13 | 6% | 3 | 11% | 10 | 5% | |

| Warning symptoms | |||||||

| No | 26 | 12% | 8 | 31% | 18 | 10% | 0.007 |

| Yes | 183 | 88% | 18 | 69% | 165 | 90% | |

| Histology | |||||||

| Intestinal | 123 | 58% | 16 | 61% | 107 | 59% | 0.384 |

| Diffuse | 56 | 27% | 8 | 31% | 48 | 26% | |

| Mixed | 12 | 6% | 1 | 4% | 11 | 6% | |

| Undifferentiated | 1 | 1% | 0 | 0% | 1 | 0% | |

| Unreported | 17 | 8% | 1 | 4% | 16 | 9% | |

| Premalignant lesionsa | |||||||

| No | 25 | 31% | 4 | 15% | 21 | 38% | 0.079 |

| Atrophy | 20 | 25% | 6 | 23% | 14 | 25% | |

| Intestinal metaplasia | 25 | 31% | 9 | 35% | 16 | 29% | |

| Dysplasia | 11 | 11% | 7 | 27% | 4 | 7% | |

| Location | |||||||

| Proximal (fundus/cardia) | 32 | 15% | 0 | 0% | 32 | 18% | 0.010 |

| Medial (body) | 66 | 32% | 3 | 12% | 63 | 34% | |

| Distal (antrum/angular incisure) | 90 | 43% | 20 | 76% | 70 | 38% | |

| Gastric remnantb | 10 | 5% | 3 | 12% | 7 | 4% | |

| Multifocal (≥2 parts) | 11 | 5% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 6% | |

| Stage | |||||||

| I | 40 | 19% | 26 | 100% | 14 | 8% | <0.001 |

| II | 32 | 15% | 0 | 0% | 32 | 17% | |

| III | 24 | 11% | 0 | 0% | 24 | 13% | |

| IV | 105 | 50% | 0 | 0% | 105 | 57% | |

| Undefined | 8 | 4% | 0 | 0% | 8 | 4% | |

| Treatment | |||||||

| Curative intent | 81 | 39% | 26 | 100% | 55 | 30% | <0.001 |

| Endoscopic resection | 2 | 1% | 2 | 8% | 0 | 0% | |

| Surgical R0 | 68 | 33% | 24 | 92% | 44 | 24% | |

| Surgical R1 | 11 | 5% | 0 | 0% | 11 | 6% | |

| Palliative | 88 | 42% | 0 | 0% | 88 | 48% | |

| Surgical R2 | 14 | 7% | 0 | 0% | 14 | 8% | |

| Chemotherapy/radiotherapy | 74 | 35% | 0 | 0% | 74 | 40% | |

| Comfort | 40 | 19% | 0 | 0% | 40 | 22% | |

| Performance status (grouped) | |||||||

| 0/1 | 162 | 77% | 24 | 92% | 138 | 75% | 0.031 |

| 2 | 20 | 10% | 2 | 8% | 18 | 10% | |

| 3/4 | 27 | 13% | 0 | 0% | 27 | 15% | |

| Death | |||||||

| No | 58 | 28% | 22 | 85% | 36 | 20% | <0.001 |

| Yes | 150 | 72% | 4 | 15% | 146 | 80% | |

AGC: advanced gastric cancer; EGC: early gastric cancer; GC: gastric cancer.

Characteristics of patients with EGC and curative potential if ESD had been performed.

| No. | Location | Warning symptom | cTNM | Resection type | Morphology | Size | Histology | Differentiation | Depth | Involvement | Curative criteria if ESD | Follow-up (months) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lymphatic | Vascular | Lymph nodes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Medial third | No | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | 4cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (504μm) | No | No | 0/9 | No | 46.2 |

| 2 | Medial third | Yes | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-I | 4cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pTis | No | No | 0/12 | Yes (cc) | 69.4 |

| 3 | Medial third | No | T2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Poorly differentiated | ypT1b (N/A) | N/A | N/A | 0/7 | N/A | 43.3 |

| 4 | Distal third | Yes | T0-1N0M0 | Mucosectomy | 0-IIc | 1cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1is | No | No | N/A | Yes (cc) | 31.3a |

| 5 | Distal third | Yes | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIc | 2.5cm | Mixed | Poorly differentiated | pT1a | No | No | 0/4 | No | 2.2a |

| 6 | Distal third | Yes | T1-2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-I | 3cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1a | No | No | 0/11 | Yes (ec: a) | 28.6 |

| 7 | Distal third | Yes | T1-2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIc | 1.5cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (381μm) | No | No | 0/23 | Yes (ec: d) | 51.3 |

| 8 | Distal third | Yes | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-III | 1.7cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (not avail.) | No | No | 0/x | Yes (ec: d) | 15.8 |

| 9 | Distal third | Yes | T2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIc | 3cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (3689μm) | No | No | 0/28 | No | 31.6 |

| 10 | Distal third | No | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | 2.5cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (4667μm) | No | No | 0/20 | No | 61.8 |

| 11 | Distal third | No | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-III | 1cm | Diffuse | Signet ring cells | pT1b (not avail.) | No | No | 0/x | No | 68.8 |

| 12 | Distal third | Yes | T1-2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIc | 1.2cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pTis | No | No | 0/9 | Yes (cc) | 58.2 |

| 13 | Distal third | No | T1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIc | 1.5cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pTis | No | No | 0/x | Yes (cc) | 68.1 |

| 14 | Distal third | Yes | T0-1N0M0 | Mucosectomy | 0-IIc | 1cm | Not avail. | Differentiated | pTis | No | No | N/A | Yes (cc) | 20.9a |

| 15 | Distal third | Yes | T2N+M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Signet ring cells | ypT1b (N/A) | N/A | N/A | 0/28 | N/A | 17.7 |

| 16 | Distal third | Yes | T2N+M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Poorly differentiated | ypT0 | N/A | N/A | 0/24 | N/A | 41.6 |

| 17 | Distal third | Yes | T3N+M0 | Surgical | 0-III | N/A | Intestinal | Differentiated | ypT0 | N/A | N/A | 0/x | N/A | 63.7 |

| 18 | Distal third | No | T2-3N+M0 | Surgical | 0-III | N/A | Diffuse | Signet ring cells | ypT0 | N/A | N/A | 0/8 | N/A | 70.6 |

| 19 | Distal third | No | T2-3N+M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Intestinal | Poorly differentiated | ypT1a | N/A | N/A | 0/13 | N/A | 42.6 |

| 20 | Distal third | Yes | T2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Signet ring cells | ypT1a | N/A | N/A | 0/17 | N/A | 44.0 |

| 21 | Distal third | Yes | T3N+M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Intestinal | Differentiated | ypT1b (N/A) | N/A | N/A | 0/37 | N/A | 22.7 |

| 22 | Distal third | No | T2-3N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Poorly differentiated | ypT1b (N/A) | N/A | N/A | 0/33 | N/A | 43.3 |

| 23 | Distal third | Yes | T2N+M0 | Surgical | 0-IIb | N/A | Diffuse | Poorly differentiated | ypT1b (N/A) | N/A | N/A | 0/23 | N/A | 38.4 |

| 24 | Remnant | Yes | T0-1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-IIa | 2cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (2850μm) | Yes | No | 0/4 | No | 22.3a |

| 25 | Remnant | Yes | T0-1N0M0 | Surgical | 0-III | 1.5cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (229μm) | No | No | 0/10 | Yes (ec: d) | 28.8 |

| 26 | Remnant | Yes | T2N0M0 | Surgical | 0-I | 2.4cm | Intestinal | Differentiated | pT1b (8000μm) | No | No | 0/13 | No | 16.7 |

cc: classic criterion; cTNM: clinical stage; ec: expanded criterion; EGC: early gastric cancer; ESD: endoscopic submucosal dissection; N/A: not applicable; not avail.: not available. For level of submucosal involvement in the cases of pT1b that were not available, we assumed infiltration of the submucosa <500μm.

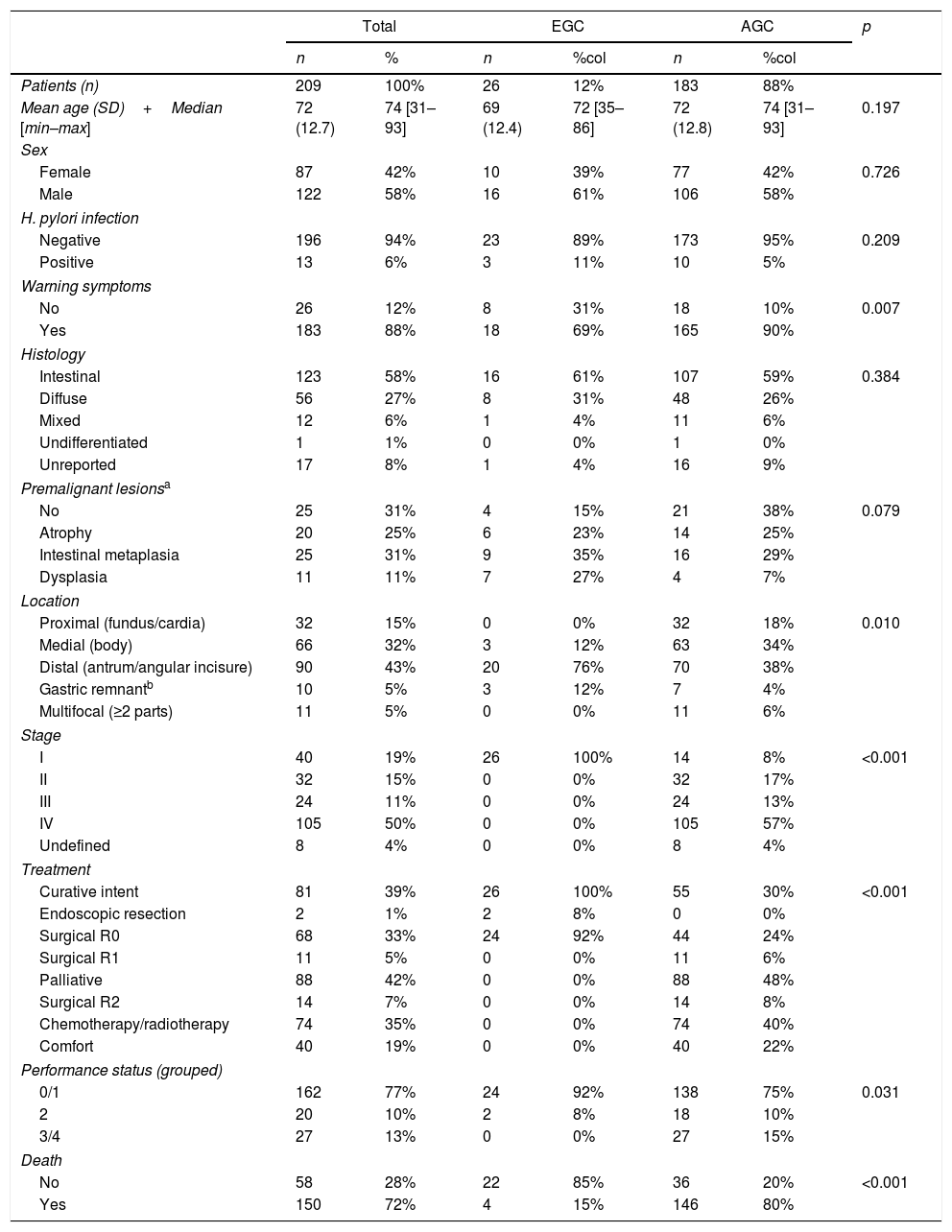

When EGC was compared to AGC, there were no significant differences with regard to mean age (69 years vs. 72 years; p=0.19), sex (61% men vs. 58% women; p=0.72), HP infection (11% vs. 5%; p=0.21), presence of premalignant lesions (85% vs. 62%; p=0.07) or intestinal histological type (61% vs. 59%; p=0.38). When EGC was compared to AGC, there were significant differences with regard to location (it was located in the distal third in 76% vs. 38%; p=0.01), warning symptoms (69% vs. 90%; p<0.01), treatment with curative intent (100% vs. 30%; p<0.01) and performance status (0–1: 92% vs. 75%; p=0.03). In addition, all patients with EGC were classified as stage 1, and only 8% of AGC patients entered this category (p<0.01) (Table 1).

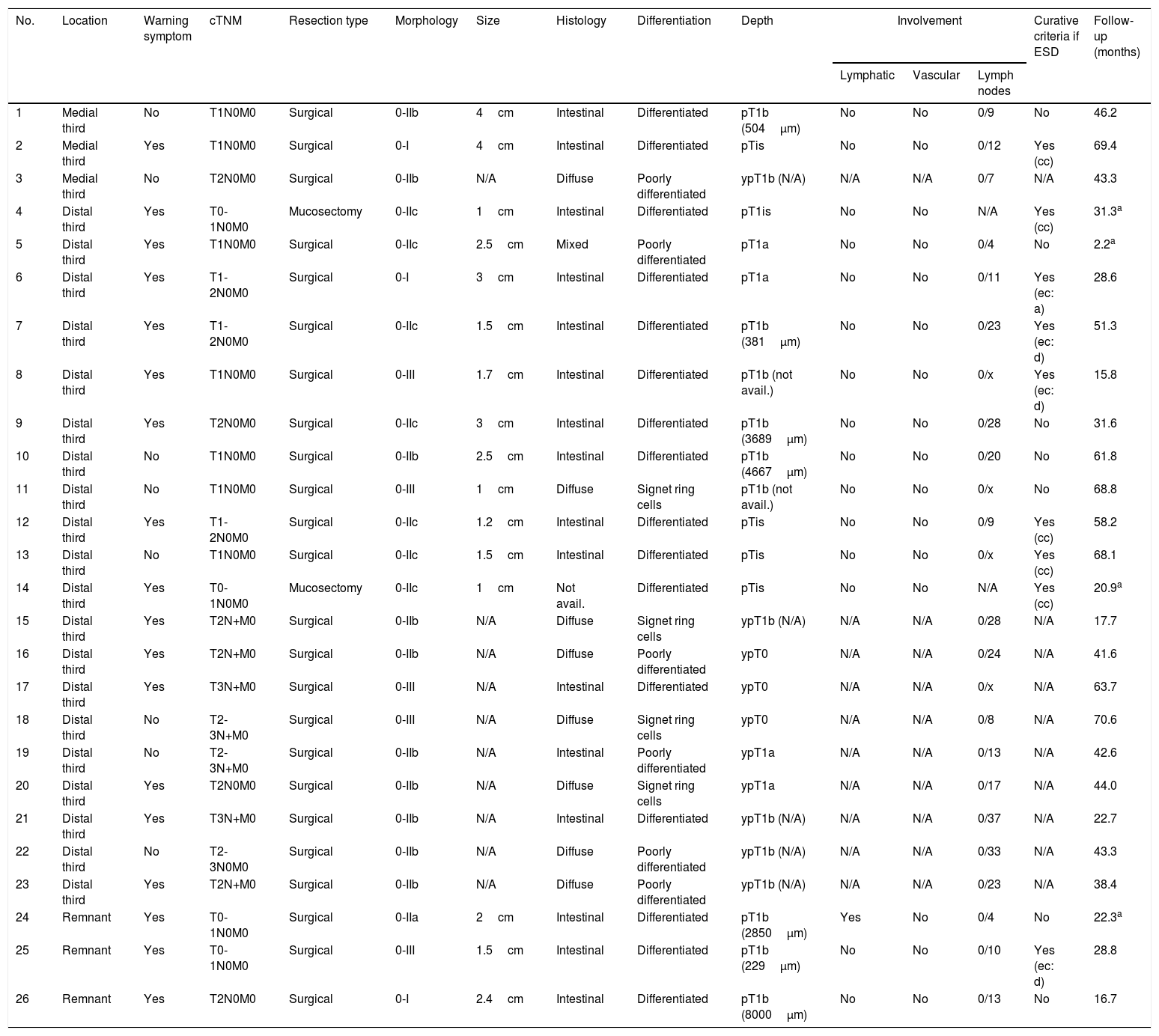

When we evaluated patients with EGC, we found that 27% (7/26) of patients could have avoided surgical treatment had they undergone less invasive treatment, such as submucosal endoscopic dissection: 3 cases met the classic curative criterion and 4 cases met the expanded curative criterion (one case met the “a” expanded criterion and 3 cases met the “d” expanded criterion) (Table 2).

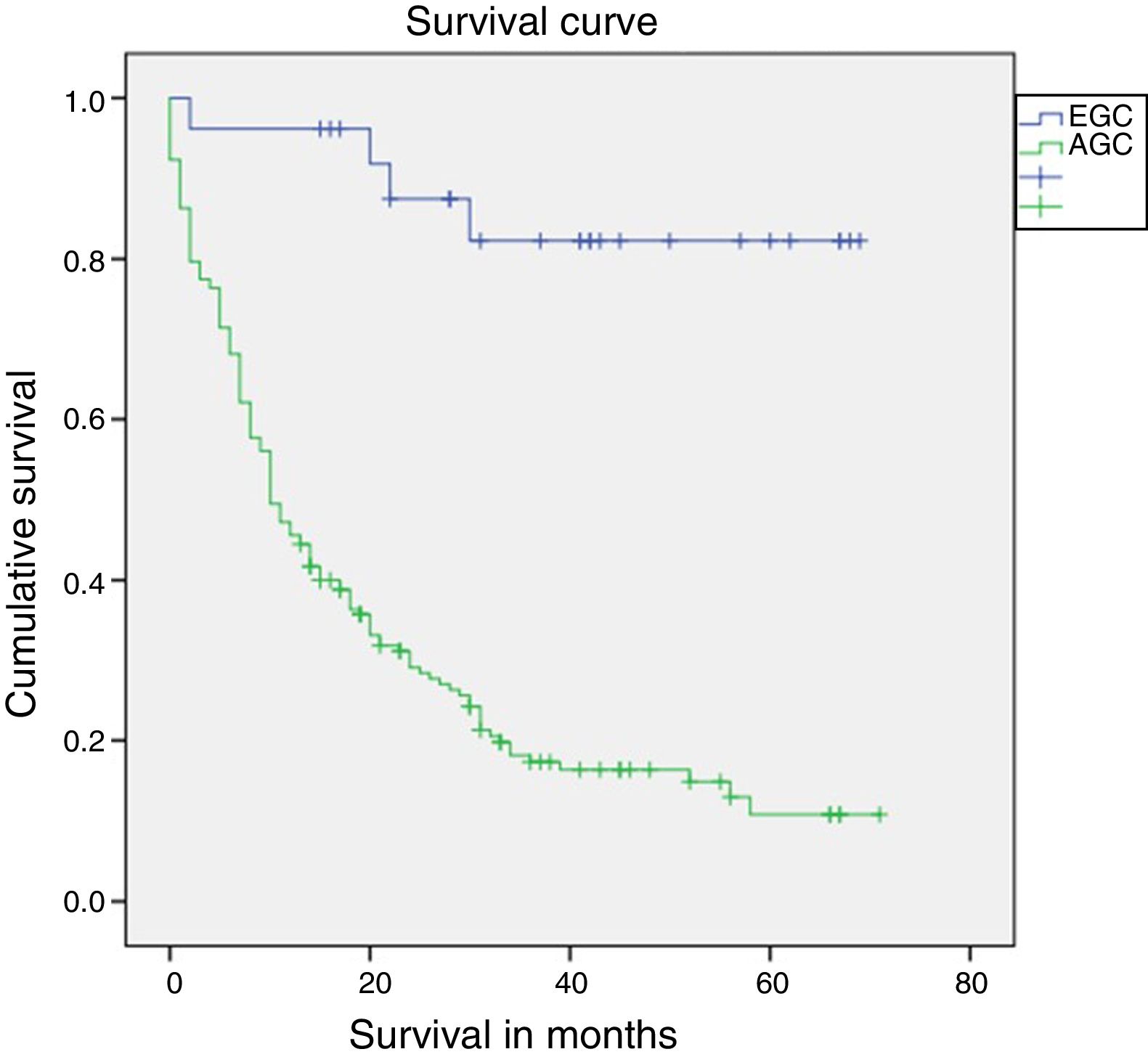

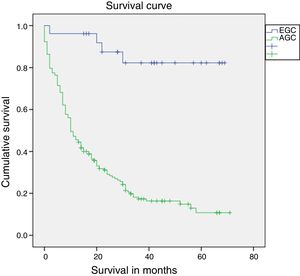

Median follow-up was 14 months (interquartile range: 0–71 months). Survival after one year was statistically superior in patients with EGC compared to patients with AGC (96.2% vs. 45.9%; log-rank p<0.01) (Fig. 2). Survival in patients who completed 5 years of follow-up (91 patients) was also higher in patients with EGC (72.7% vs. 11.3%; log-rank p<0.01). Mortality in patients with EGC was 15% (4 patients). One patient died in the first year due to a surgery-related complication (peritonitis secondary to dehiscence of the duodenal anastomosis), and the other 3 deaths occurred after the first year secondary to causes unrelated to the perioperative period (one patient due to a relapse of GC with liver metastases, one patient from cholangiocarcinoma of the common hepatic duct and one patient from bilateral pneumonia).

DiscussionThe incidence of GC is gradually decreasing all over the world due to primary prevention measures such as better food preservation and eradication of HP.1,2 Moreover, in Japan, the proportion of EGC has been improved by up to 50% thanks to the implementation of a population screening programme as a secondary prevention measure.13 In one European country, namely France, the proportion of EGC has remained low (6.7%) in recent decades.17 In our series it accounted for 12% of all GCs, within the range previously reported in different Spanish series.19–24 On the other hand, the proportion of GC may be overestimated when it is only calculated among surgical patients.17,27 In our study, the proportion of GC among surgical patients was 30.4%, with an improvement in the selection of candidates for surgery when compared to studies published in recent years in Spain (Table 3).23,24,28–30 This improvement can also be accounted for by advances in neoadjuvant treatments.30 In our study, we identified 10 patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy with a surgical specimen classified as EGC (Table 2).

Frequency of EGC in published series in Spain.

| Author | Location | Study period | EGC out of patients who underwent surgery | EGC out of all patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velloso et al.19 | Andalusia | 1971–76 | Not avail. | 3.6% |

| Velloso and Pou20 | Multicentre | <1978 | Not avail. | 2.8% |

| Oleagoitia et al.28 | Basque Country | 1975–85 | 14.6% | Not avail. |

| Aguayo et al.21 | Murcia | 1982–85 | Not avail. | 15.3% |

| Bordas et al.23 | Catalonia | 1987–88 | 17.8% | 12% |

| Moreto et al.22 | Basque Country | 1989a | Not avail. | 10% |

| Pérez López de Briñas24 | Catalonia | 1981–90 | 16.2% | 7.2% |

| Bianchi et al.29 | Catalonia | 1980–96 | 21% | Not avail. |

| Bianchi and Espin30 | Catalonia | 1996–2000 | 29.5% | Not avail. |

| 2006–11 | 20.5% | Not avail. | ||

| Delgado-Guillena et al. | Catalonia | 2012–16 | 30.4% | 12% |

EGC: early gastric cancer; not avail.: not available.

GC is more common in men and in patients around 60 years of age.27 In our series, both EGC and AGC were more common in men, with no differences in terms of distribution between the two groups. Similarly, no differences were seen in terms of mean age of patients with EGC (69 years) and AGC (72 years). Age at diagnosis of EGC in our series was older than in series previously reported in European countries (59.9 years) and in Japanese patients (57.8 years).27

The main risk factor for GC is HP infection; however, in our cohort, only 6% had HP infection when they were diagnosed with GC, leading us to assume prior eradication in an unknown percentage of patients. It has been reported that GC risk does not disappear following eradication of HP and occurrence of changes such as atrophy and intestinal metaplasia; therefore, endoscopic monitoring is recommended.14,31

In Spain, population screening for GC (in asymptomatic patients) is not cost-effective14; therefore, a diagnostic method such as an OGD is usually performed in the presence of symptoms.4 Patients with EGC usually have unspecific symptoms such as dyspepsia, in some cases associated with alarm symptoms such as anaemia, gastrointestinal bleeding (less than 25%) and weight loss (less than 40%), whereas AGC is more commonly associated with warning symptoms.8,27 In our study, warning symptoms were seen in 18/26 (69%) patients with GC; the most common were anaemia in 9/26 (35%) cases, weight loss in 4/26 (15%) cases and gastrointestinal bleeding in 3/26 (12%) cases. The high frequency of warning symptoms may have been due to the lesions’ morphological characteristics; for example, in 12 cases, lesions were flat-depressed (0-IIc) or excavated (0-III). Multiple alarm symptoms were seen in 6 of the 10 patients classified as EGC after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 2).

GC is an adenocarcinoma in more than 90% of cases and tends to be predominantly of the intestinal type. It is currently accepted that GC is the end result of a series of changes such as atrophic chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and finally adenocarcinoma. This process is multifocal; usually it starts in the angular incisure, then spreads towards the stomach walls.8 In our study, 69% of the patients treated with curative intent (mucosectomy or surgical R0/R1) had premalignant lesions with no significant differences observed between EGC and AGC. Of all gastric adenocarcinomas, the intestinal type was the most common in both groups (61% in EGC and 59% in AGC).

GC location was similar to that reported by Miguélez-Ferreiro et al.,32 with 43% of cases in the distal third (antrum and angular incisure), followed by 32% of cases in the medial third (body); however, the distribution of EGC compared to AGC was more common in the distal third (76% vs. 38%), followed by the medial third (12% vs. 34%). All cases of EGC and only 8% of cases of AGC were classified as stage I; despite this, the total proportion of patients in stage I was less than 20%, similar to that reported previously in a Spanish hospital.32

Endoscopic resection of EGC (mucosectomy or submucosal dissection) serves as a diagnostic method, and when the resected lesion meets curative criteria, surgical treatment can be avoided in a high percentage of patients.33 For a patient to be considered cured, en bloc resection of the lesion must be performed, with clear margins and no lymphovascular invasion. A patient is regarded as cured if they meet the classic curative criterion (a well-differentiated intramucosal adenocarcinoma ≤2cm) or any of the expanded criteria.11 The expanded criteria have a low risk of lymph node involvement.33,34 However, the risk is not null and must therefore be evaluated by a multidisciplinary committee, particularly adenocarcinoma of undifferentiated histology which involves a more aggressive biology (“c” expanded criteria) and adenacarcinoma invading the submucosa (“d” expanded criteria). The incorporation of the expanded curative criteria has been shown to maintain a low risk of spread to the lymph nodes, a high cure rate and outcomes similar to surgery.33,34 Despite these advances in endoscopic treatment of EGC, we only detected 2 cases of mucosectomy and no cases of submucosal dissection. When we evaluated the surgical specimens from the patients with EGC, we found that 27% (7/26) of the patients could also have benefited from a less invasive endoscopic curative treatment with the same outcomes as surgery with lymph node dissection. Although cases of distal EGC are more likely to undergo an endoscopic approach, in Spain, implementation of submucosal dissection is limited by the low frequency with which EGC is diagnosed and the costs associated with the procedure.35

All cases of EGC received treatment with curative intent (2 cases of endoscopic treatment and 24 cases of surgical treatment). We did not identify any cases of EGC in which a decision not to treat was made. Since the concept of EGC was introduced in Japan (1962), these patients have been seen to have a 5-year survival rate ≥90% following treatment with lymph node dissection10; however, in Western countries, the survival rate tends to be slightly lower (84%–92%).27 We also observed a lower 5-year survival rate (72.7%). The difference has been attributed to surgical technique-related considerations.27 In our study, one (3.8%) of the patients with EGC died due to a perioperative complication. Guadagni et al. estimated operative mortality in EGC at 4.1% (including anastomotic dehiscence and other perioperative complications); and in long-term follow-up (5 or 10 years), pneumonia was a common cause.36 Given the limited number of patients with EGC, these 4 cases may have had a greater impact on the survival analysis.

The purpose of our study was not to evaluate surgical technique or chemotherapy type. However, our study's definition of EGC was based on surgical specimen examination and did not take into account whether or not the patient had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The European guidelines establish neoadjuvant chemotherapy as standard treatment in a selected group of patients (clinically operable GC >T1N0), whereas the Japanese guidelines do not.6,11 Pathology-based staging is the best prognostic factor, and based on this, clinical staging is known to perhaps over- or under-stage GC (by up to 23%).37 Consequently, in the group of patients with EGC who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy, we might have introduced bias by initially including over-staged patients (true EGC) and responders to neoadjuvant treatment (initial involvement deeper than the submucosa). Nevertheless, due to the introduction of neoadjuvant treatment in recent years, studies that are attempting to evaluate the prognosis for ypTNM and pTNM staging are being conducted.38 On this basis, future studies should take this factor into account and evaluate the prognosis for ypT1 and pT1 patients.

While our data did not come from a population registry, they did correspond to patients seen in a well-defined health area where care was provided at 3 county hospitals with endoscopy units, with surgical care for GC (non-cardia GC) and the pathology unit centralised at one of them.

The main weakness of our study was its retrospective design, which hampered the collection of data such as HP treatment before GC diagnosis and use of proton pump inhibitors, which in some cases may mask or delay the diagnosis of GC. The absence of a computerised registry in prior years made it impossible for us to compare the current frequency of EGC to previous data from our same healthcare area. In addition, we lacked access to death certificates; therefore, vital status at the end of the study was considered for the survival analysis.

The Spanish clinical practice guidelines recommend an OGD in patients over 55 years of age with dyspepsia and in patients with recurrence of symptoms or any warning symptom4; however, the diagnosis of EGC in patients of an age similar to advanced GC with a high frequency of alarm symptoms led us to suspect a lack of treatment adherence. Similarly, in Spain the diagnosis of GC may reportedly go unnoticed, in many cases due to a failure to recognise subtle mucosa lesions in an OGD.39,40 To improve ECG detection, it is important to learn to detect EGC and to improve OGD quality. The European clinical practice guidelines on OGD quality16 recommend a meticulous inspection of the gastric mucosa (at least 7min), suitable photographic documentation (at least 10 photographs altogether, and at least 5 photographs of the gastric cavity) and the performance of biopsies according to protocols (2 biopsies of the antrum and 2 biopsies of the body of the stomach) in patients with a high risk of GC. The quality of an OGD can be enhanced by means of a simple training programme.41 Moreover, the frequency of EGC is easy to measure (cases of T0-1 GC out of all cases of GC in a given period) and the definition thereof has remained unchanged over time; hence, it could serve as an indicator on endoscopy units to evaluate strategies in secondary prevention of GC.

ConclusionThe frequency of EGC was low in our health area (12% of cases of GC) and similar to figures previously reported in Spain. EGC presented in assocation with a high percentage of warning symptoms, was located mainly in the distal third of the stomach (antrum and angular incisure) and had a better prognosis than AGC. Measures must be implemented to increase the proportion of cases of EGC. In view of the better prognosis of early-stage GC and the possibility of endoscopic treatment, endoscopists must be trained to recognise these lesions and perform an OGD according to the recommended quality criteria.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Delgado-Guillena P, Morales-Alvarado V, Ramírez Salazar C, Jimeno Ramiro M, Llibre Nieto G, Galvez-Olortegui J, et al. Frecuencia y aspectos clínicos del cáncer gástrico precoz en relación con el avanzado en un área sanitaria de España. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:506–514.