Anal tumours are quite rare and account for 2% of all colorectal malignant neoplasms. Most are either epithelial tumours or melanoma.1 Soft tissue tumours only account for 2.3% of all cases.2

We present the case of a gastrointestinal stromal tumour (GIST) with atypical location, which could represent a diagnostic challenge.

The case concerns a 52-year-old female patient originally from south-east Mexico, with seven prior pregnancies and bilateral tubal occlusion at the age of 35, with no other prior history of interest. The patient attended our centre with a 10cm mass in the anal region. It was first detected by a general practitioner as a 2cm mass one year previously and was diagnosed as probable haemorrhoids without associated symptoms. However, the mass grew rapidly with the onset of bleeding, painful bowel movements and changed stool consistency. The physical examination revealed an irregular tumour in the anal region that extended from the left ischioanal fossa to the retrorectal space with ulceration of the mucosa, with sphincter involvement and avulsion of the left levator ani.

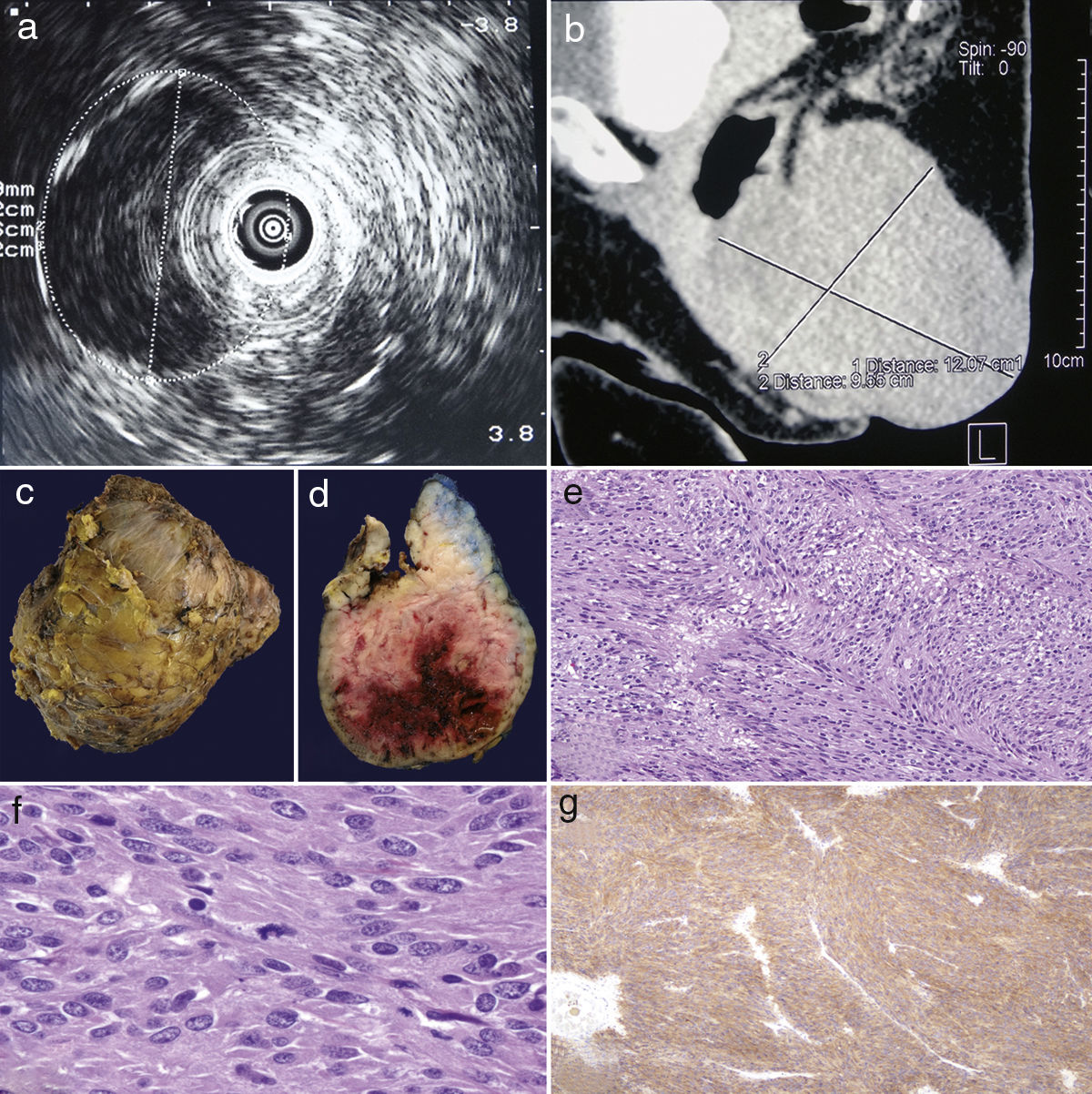

The endoanal ultrasound (Bruel & Kjaer model 1849 [Gentofte, Denmark] with Bruel & Kjaer model 1850 7MHz axial device and transducer) identified a 14× 10cm hypoechoic lesion, attached to the middle and lower rectal wall without mucosal infiltration and without apparent involvement of the anal sphincter (Fig. 1a). The CT scan revealed a well-defined lesion with irregular edges measuring 12×10×8cm, with soft tissue density, from the distal rectal wall extending caudally to the exterior of the anus (intergluteal portion), obliterating 40% of the lumen (Fig. 1b). A transanal approach was used to resect the tumour, with the patient in the prone position and with the buttocks stretched apart. A parasacral incision was made followed by vertical dissection from the subcutaneous tissue to the gluteus muscles, and the lower edge of the tumour and the ischial tuberosity were identified. The sacrotuberous ligament was sectioned and the tumour released from the gluteus maximus (resection would have been considered in the event of muscle invasion, or resection of the lower part of the sacrum below S3 to preserve the root of the pudendal nerve, if necessary), followed by medial and cranial dissection with release of the rectum, the anal sphincter and the levator ani. As the tumour involved part of the external sphincter, this was resectioned and reconstructed. The dissection plane was located in the intersphincteric space, which allowed us to preserve the internal anal sphincter in its entirety. The wound was closed by planes. This curative approach was similar to that performed for any mesenchymal tumour in the intersphincteric space, trying to complete the resection with negative surgical margins. The patient had no faecal consistency abnormalities in the post-operative period.

(a) Endoanal ultrasound with hypoechoic lesion attached to the rectal wall, (b) sagittal plane CT scan, a neoplastic lesion in the anorectal region is identified, (c) external macroscopic appearance, (d) macroscopic appearance upon section, (e) a neoplastic lesion composed of irregular and intertwined cell bundles is observed (haematoxylin and eosin, 10×), (f) the neoplastic cells are tapered with ovoid nuclei, note atypical mitoses, and (g) positive immunoreaction for CD117 in the neoplastic cells.

Macroscopically, the lesion was a dark yellow irregular ovoid with a firm consistency, measuring 14×11×9cm and weighing 635g. Upon section, the surface was observed to be fasciculated, whitish-grey and with haemorrhagic areas (Fig. 1c and d). Microscopically, a neoplastic lesion composed of long and wide cell bundles was observed. The cells were tapered and polygonal with dispersed granular chromatin nuclei and the immunohistochemistry was positive for CD117 and CD34, and negative for desmin, PS-100 and smooth muscle actin (Fig. 1e–g). In addition, numerous mitoses were identified (120–140 mitoses in 50 high-power fields). A diagnosis of high-risk gastrointestinal stromal tumour was established. The patient's clinical course was favourable and she was discharged eight days after the surgery. She was offered an appointment to assess the start of adjuvant therapy with imatinib, but she withdrew from follow-up. Because there was no evidence of metastasis, abdominal–pelvic resection following histopathological diagnosis was not considered.

Although gastrointestinal stromal tumours are the most common mesenchymal neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract, they tend to occur in the stomach and are rarely reported in the anorectal region.1–3 The originate in the cells of Cajal, which act as a pacemaker in intestinal peristalsis, and they often express CD117 (c-kit) and CD34.2–5 GISTs of the anal region are rare, accounting for just 0.1% of all GISTs, and primarily affect men in their 50s.2,4

They clinically manifest as an exophytic mass in the intersphincteric space with haematochezia, pain, feeling of a mass, constipation or anaemia, although they can also be asymptomatic.2–5 This makes it difficult to establish a suspected diagnosis as these symptoms are similar to those of other tumours that may manifest in the anal canal, such as squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, melanoma or sarcomas.6

Imaging studies reveal a well-defined intramural mass with soft tissue density and exophytic growth, sometimes with central necrosis,5 allowing them to be distinguished from carcinomas that tend to have irregular edges and may be associated with perirectal lymphadenopathy. However, no radiological criteria have been established to distinguish GISTs from other tumours of the anal region.7 In our case, surgery was chosen based on the results of the imaging studies performed, which could act as a guide for other cases to conduct preoperative diagnosis to decide the best surgical approach.

Diagnosis is made by histopathological study; it should be differentiated from other benign and malignant soft tissue lesions and confirmed with a positive CD117 and CD34 immune profile.2 To date, cases published in the literature of GISTs in the anal canal that express CD117 have been positive for this marker and no atypical patterns have been reported. As such, unlike the example of succinate dehydrogenase-deficient gastric GISTs, no factors have been identified on either a microscopic or molecular level that could be used to classify them into a separate group.8

Factors associated with malignancy are mitotic activity (>5 mitoses/50 HPF), tumour size (>5cm) and necrosis2–5; the first two were present in our case, which is why it was considered a high-risk tumour.

The treatment of choice is surgery and the approach depends on each individual case; either local excision with transanal approach or radical resection (abdominal–pelvic resection).2,3 Adjuvant therapy with imatinib (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) has been shown to improve survival2 and tends to be used to treat recurrence, unresectable tumour or metastasis.4 As recurrence can be as high as 62% in the first three years, close follow-up is important.2 Incomplete resection is an independent risk factor that has a negative impact on disease-free survival.9 As such, every effort must be made during surgery to achieve resection with negative margins for neoplastic cells.

Because anal GISTs are rare, there is a lack of consensus over which treatment is most effective. The reporting of these cases, their management and the clinical outcomes is therefore extremely important. A pathological study is vital to rule out other causes of malignancy, and long-term follow-up is essential due to the high rate of recurrence.

FundingNo sponsorship of any kind was received for the conduct of this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: TecoCortes JA, Grube-Pagola P, Maldonado-Barrón R, Remes-Troche JM, Alderete-Vázquez G. Tumor del estroma gastrointestinal en canal anal: a propósito de un caso con localización atípica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:389–391.