Intestinal lipomas are the most common benign tumours after adenomatous polyps. They can originate in any segment of the gastrointestinal tract, although they are more common in the large intestine. The prevalence in the general population is estimated to be in the range of 0.2% to 4.4% and they represent 1.8% of all benign lesions of the colon. They are usually small (less than 2 cm), their size is positively correlated with the presence of symptoms and they can cause potentially serious complications when they become larger than 4 cm (also called giant lipomas1).

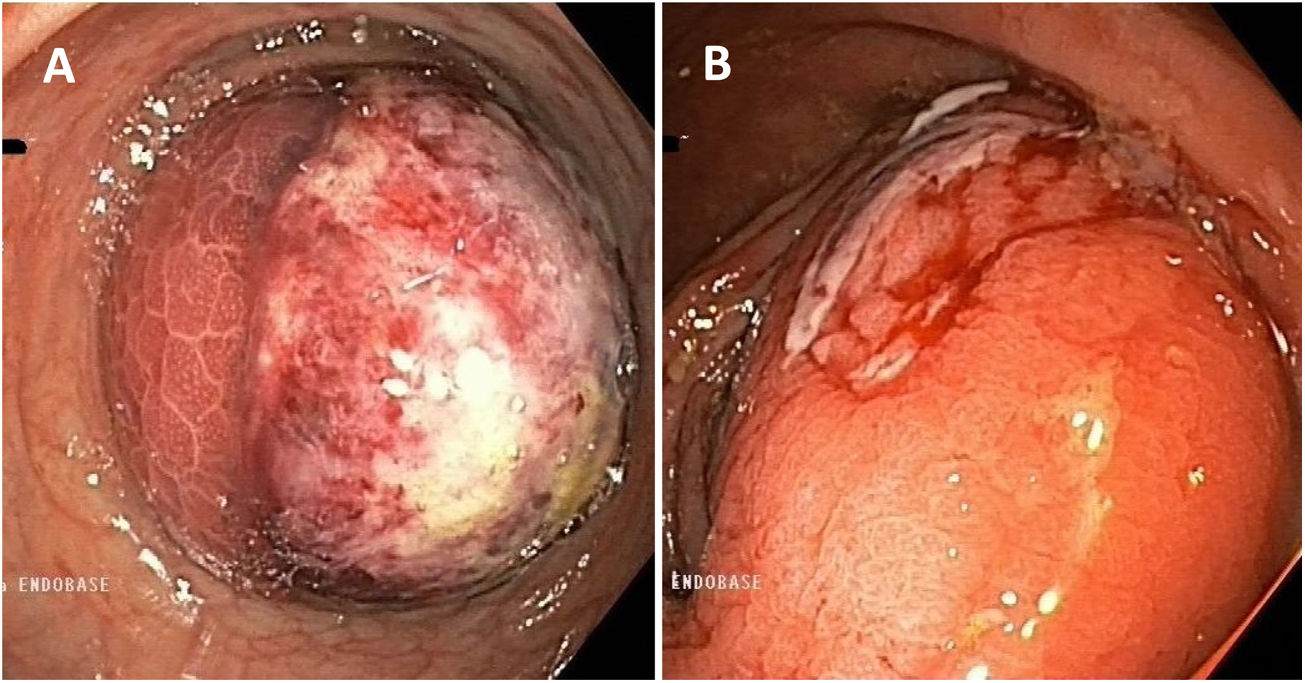

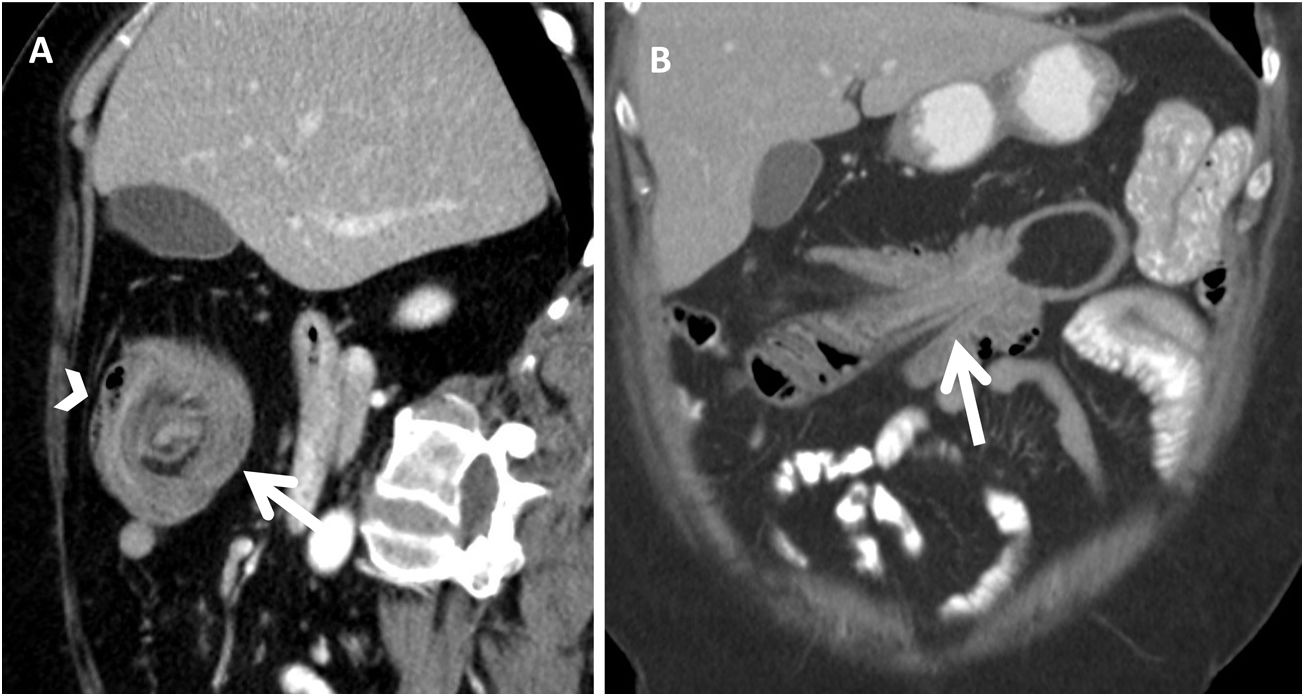

We describe the case of a 56-year-old female with a history of obesity, multinodular goiter and fibromyalgia. She went to the Accident and Emergency department complaining of right abdominal pain and haematochezia; she had no changes in bowel habit, weight loss, anorexia or fever. Blood analysis showed mild anaemia (Hb 11.3 g/dl); other parameters were normal. Colonoscopy revealed a pedunculated polypoid lesion about 5 cm in diameter in the hepatic flexure, with no clear glandular pattern and ulcerated areas oozing blood on the surface, causing almost complete stricture of the lumen of the colon (Fig. 1). Despite having active bleeding, management was conservative due to the small amount and diffuse nature. The colonoscopy was completed with no other findings; biopsies were taken from the non-bleeding areas of the lesion, the histology of which revealed focal hyperplastic changes. As malignancy was suspected and the patient had persistent bleeding (even though of small amounts), an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan was performed, which showed a rounded image with concentric rings of different densities (sagittal sections) and an image of the colon within the colon (in the coronal sections), findings compatible with colocolic intussusception caused by a mass with lipomatous characteristics, without signs of intestinal obstruction or distension of loops (Fig. 2). In view of these findings, we decided to perform an extended right hemicolectomy with ileocolic anastomosis. Pathology examination of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of a 55 × 43 mm submucosal lipoma, with mucosal ulcerations and erosions. There was no evidence of dysplasia or carcinoma in the surgical specimen, or pathological lymphadenopathy. At the postoperative check-up, the patient was asymptomatic, with normal intestinal transit and no complications.

Computed tomography. A) Transverse view of intestinal intussusception; a “target” or “doughnut” image can be seen (arrow) with a lipoma in its centre, as well as mesenteric vessels and fat in the periphery (arrowhead). B) Longitudinal view of the intussusception; the colon can be seen with thickened walls and mesenteric fat and vessels entering the intussusception.

Lipomas of the colon are slow-growing mesenchymal tumours which originate in the submucosal (90%) or subserosal (10%) layers and mainly affect women in their forties and fifties.1,2 The majority of cases are diagnosed incidentally during colonoscopies, when they are identified by their typical yellowish colouring and well defined, smooth borders. Endoscopic diagnosis is reliable in over 60% of cases. The presence of necrosis, superficial ulceration or hardness when taking biopsies can make it difficult to differentiate lipomas from a malignant lesion, so in these cases CT or magnetic resonance imaging is needed. Sometimes, however, in the event of diagnostic uncertainty or complications, segmental resection of the colon is opted for at an early stage, with the diagnosis confirmed after pathology examination of the surgical specimen.1

Lipomas larger than 4 cm in size, considered as giant lipomas, cause symptoms in 75–100% of cases and complications such as anaemia, intussusception and intestinal obstruction.1 With regard to bleeding, although rare, there have been reports in the literature of lipomas with ulceration of the mucosa that cause gastrointestinal bleeding.2 Taking biopsies in these cases is a debated issue, as it can increase the risk of bleeding and the possibility of sampling errors means the presence of malignancy cannot be ruled out.

Intestinal intussusception is the introduction of a proximal segment of the intestine into a more distal segment; it represents only 1–5% of intestinal obstructions and can be caused by malignancy (lymphoma, adenocarcinoma) or have a benign cause, such as intraluminal lipomas. The diagnosis of intussusception is confirmed by imaging tests, with CT being the most sensitive and specific (83–100%). The characteristic finding is the presence of colon within colon or ileum within colon, as was found in the case we present here. CT will also show the existence of proximal occlusion and any distension of intestinal loops.3,4

Due to their benign nature, most colon lipomas do not require treatment, except when there is uncertainty about the diagnosis, the patient has symptoms or they are more than 2 cm in size. Endoscopic resection assisted by endoloops or endoclips can be a treatment option in experienced hands. A prior endoscopic ultrasound is advisable to identify the size, borders, vascularisation, layer of origin and extension of the serosa or muscle within the peduncle and to minimise the risk of perforation.1,2 Surgical resection is the most widely used treatment for colon lipomas: it is indicated in cases of giant, sessile lipomas, suspected malignancy, serious complications (obstruction, intestinal intussusception, perforation or haemorrhage) or muscle or serous layer involvement (in which endoscopic resection is contraindicated). These days, segmental resections of the colon are most common, using a laparoscopic or open approach, with the rate of complications being low.2,5

We are able to conclude that giant lipomas of the colon are uncommon findings in routine colonoscopies and that the coexistence of two complications in the same patient, in addition to endoscopic characteristics indistinguishable from a neoplastic lesion, is very rare. Therefore, when we detect a giant lipoma, particular attention must be paid to its endoscopic characteristics, using endoscopic ultrasound to assess its resectability, as the likelihood of future complications is high and they can potentially be serious.

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Martín Domínguez V, Moreno-Monteagudo JA, Santander C. Lipoma cólico gigante complicado con intususcepción y hemorragia digestiva baja. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:126–128.