Hepatoblastoma is the most common hepatic tumour in children, accounting for 90% of all malignant liver tumours. It is usually diagnosed during the first 3 years of life.1,2 Signs and symptoms are very subtle, with the main clinical manifestations including abdominal distension and a palpable abdominal mass. For diagnosis, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, compatible imaging studies and suggestive signs and symptoms are required; however, histological diagnosis of the tumour also plays an important role.1 Survival rates of these patients have improved significantly over the last 3 decades, currently achieving rates of around 75–80%. This improvement is due to advances in therapy.2

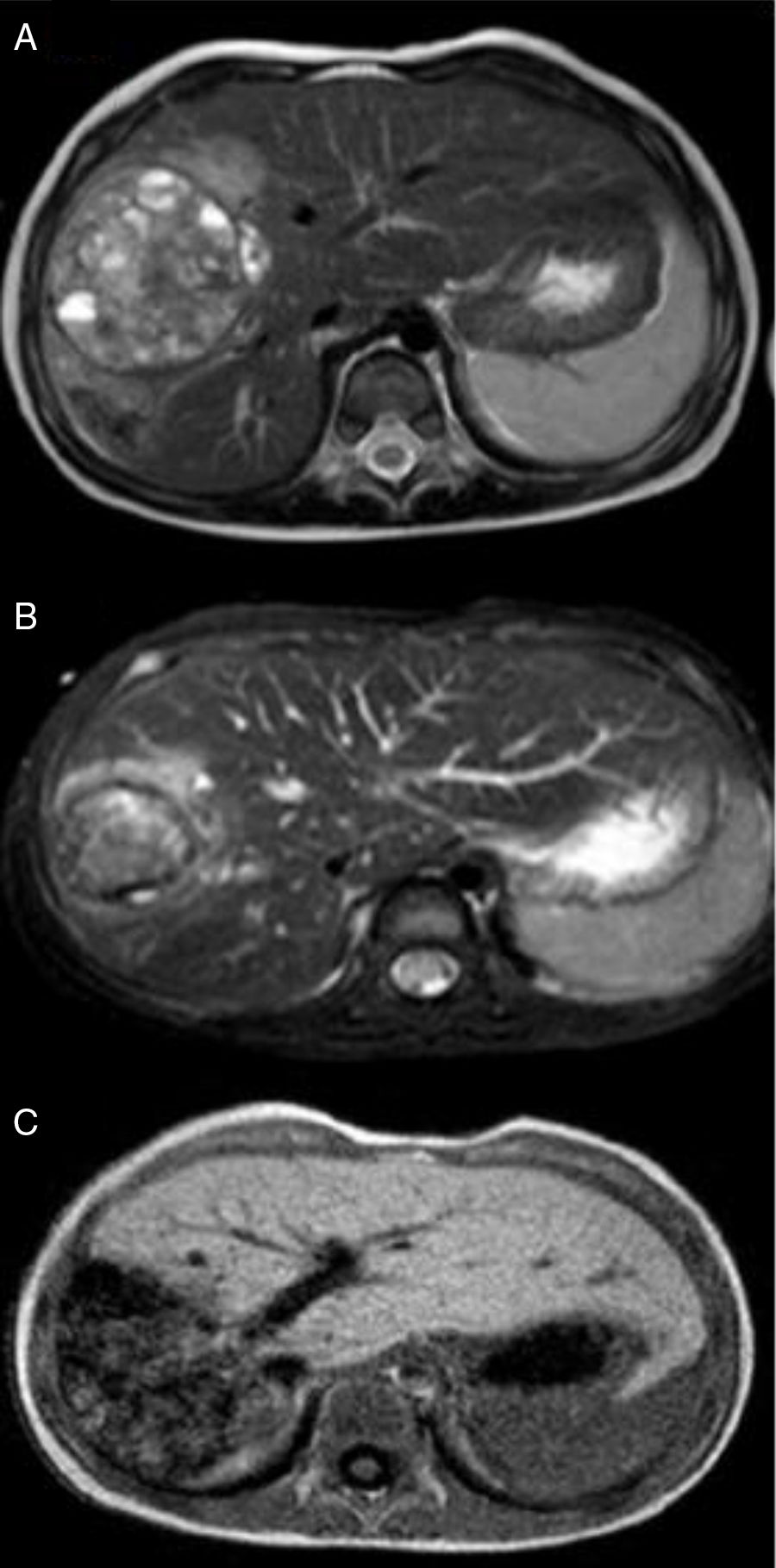

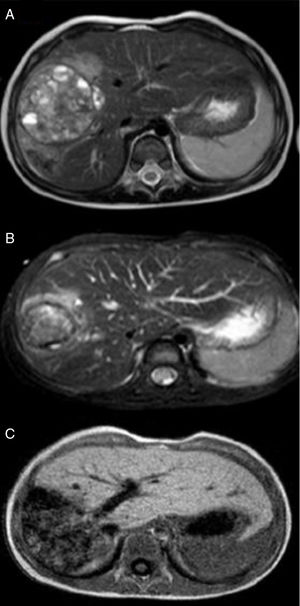

Our case study involves a 2-year-old child with no personal or family history of disease, good overall health and no previous symptoms. The child visited the paediatric emergency department with symptoms of bronchiolitis. Upon physical examination, hepatomegaly was detected with no other findings. As a result, an abdominal ultrasound (hepatomegaly) and AFP tests (152,370ng/ml) were performed. Since a liver tumour was suspected, the child was referred to the paediatric oncology clinic where he underwent imaging studies (Fig. 1: bulky tumour measuring 11cm long×6cm thick, confined to the right lobe of the liver, without exceeding beyond the round ligament, with no portal vein thrombosis, but with compression/encasement of the hepatic hilar vessels) and a liver biopsy, which confirmed the diagnosis of foetal hepatoblastoma. Taking into consideration the Pretreatment Extent of Disease (PRETEXT) staging and risk stratification system proposed by the Société Internationale d’Oncologie Pédiatrique-Epithelial Liver Tumor Study Group (SIOPEL), the tumour was classified as PRETEXT III, considered inoperable, and therefore treatment was started with cisplatin.3 The subsequent decision to start more aggressive chemotherapy with cisplatin, carboplatin and doxorubicin was due to suspected encasement of the hepatic hilar vessels. After 3 cycles of chemotherapy, an MR angiogram was performed which revealed overall reduction of the tumour mass, consisting of 3 adjacent nodules: the most central region had a transverse and anteroposterior diameter of 5.4cm and a craniocaudal diameter of 6.7cm; the posterior region showed a mass with a transverse diameter of 4.2cm and the most anterior region showed a third tumour component measuring around 2cm, with no evidence of portal vein thrombosis and with questionable vascular encasement (Fig. 2AFig. 2). At this point, the decision was made to combine chemotherapy with embolisation, given the hypervascular nature of the tumour, in order to reduce the tumour mass and due to the risk of extensive surgery (trisegmentectomy). Therefore, selective embolisation was performed with polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) microspheres and metal coils. A hepatic angiography revealed a large, hypervascular mass measuring approximately 7–8cm in liver segments V, VI and VIII. Microspheres were selectively released into the respective nutritive arterioles of the tumour and microcoils were released into the main nutritive arteries. Another MT angiogram was performed once month later, which revealed a significant reduction in tumour size, with reductions of 7mm in the central component, 4mm in the anterior component and 7mm in the most posterior component (Fig. 2B). This reduction in tumour size allowed for right hepatectomy, with a resection plane running along the middle hepatic vein, corresponding to the usual limit for this type of resection (Fig. 2C). The anatomical pathology description describes a narrow hepatic resection margin of 0.5cm for the resected specimen. The child completed the cycle of chemotherapy 2 months after surgery, obtaining a favourable response with a gradual decrease in AFP levels, which are currently normal.

The treatment for hepatoblastomas has advanced in recent years, resulting in better survival rates. Although treatment depends on the stage of the tumour, complete surgical resection (macroscopic and microscopic) is essential to achieve a cure.1,2 However, surgery is not possible in 50% of patients due to the advanced stage of the tumour.4 Since hepatoblastoma is more sensitive to chemotherapy, pre-operative chemotherapy helps reduce tumour volume, making resection easier, which results in a better prognosis.1,2 Unresectable, high-risk hepatoblastomas can be made resectable with chemotherapy; however, this is not always effective.4 Since they are usually hypervascular tumours, pre-operative embolisation may be effective in cases that do not respond to chemotherapy.4,5 In this child, embolisation produced satisfactory results since a significant reduction in tumour size was achieved, allowing complete surgical resection. Although pre-operative embolisation is a viable and attractive outcome, it must be analysed with caution since it may produce some complications.6

Despite the promising results of embolisation in cases of hepatoblastoma, prospective studies must be conducted in order to evaluate the risk-benefit of this approach before it can be considered a potential first-line treatment.

Please cite this article as: Ferreira H, São Simão T, Maia I, Maia A, Castro J, Gonçalves B, et al. Hepatoblastoma: éxito de terapia combinada con embolización arterial preoperatoria. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:262–264.