Listeria monocytogenes (LM) is a Gram-positive bacteria, facultative anaerobic pathogen involved in serious food-borne diseases, which is responsible for listeriosis.1 It mainly affects elderly patients, pregnant women and immunocompromised people. Infection in immunocompetent patients is rare.1,2 There are three main clinical presentations: septicaemia, central nervous system involvement, and maternal and neonatal infections.1–3 Although it is known that LM can colonise the intestine and the bile, bile duct infections and acute cholecystitis are uncommon symptoms.1,2,4 From 1963 to the present day, in the PubMed database, there are only 8 articles about LM-induced acute cholecystitis, using the terms “Listeria”, “listeriosis”, “cholecystitis”, “cholangitis”, “liver” and “bile” in the search, which means they are isolated cases.2–9

A 76-year-old male, not institutionalised, with a personal history of high blood pressure, COPD, stroke, and an appendicectomy, who was admitted to hospital due to 3 days of abdominal pain in the right hypochondrium, along with vomiting after eating. Upon examination, the patient was afebrile, haemodynamically stable, with a globular and painful abdomen in the right hypochondrium and a positive Murphy's sign. Analytically, only leukocytosis was seen (15,300/μL), with 85.3% neutrophilia. The abdominal ultrasound reported an acute calculous cholecystitis. He underwent emergency surgery, and acute cholecystitis was observed in a gangrenous phase with perivesical fluid. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed and drainage placed. After the operation, antibiotic treatment was implemented with intravenous amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (1g/8h), due to the advanced stage of cholecystitis symptoms, the age and the comorbidity of the patient. After the operation, there was only mild and self-limited bleeding because of the drainage. The microbiological study of the bile showed the presence of amoxicillin-sensitive LM. The patient was discharged 7 days after the procedure, thus completing a total of 10 days of antibiotic treatment with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid. After being discharged from hospital, a stool test was carried out, with no evidence of LM. The pathology report confirmed the diagnosis of acute cholecystitis.

It is known that LM can colonise the human intestine, with 1–12% of healthy individuals being asymptomatic carriers.9 Despite the antimicrobial activity of the bile, LM has evolved to be able to survive in the bile and in the proximal region close of the small intestine and thus infections of bile ducts, including cholecystitis, should not be surprising even if the pathogenesis of it is unknown.8,10

The capacity of LM to survive in the bile has several clinically significant consequences. Firstly, the asymptomatic colonisation of the bile by LM may not be pathogenic per se, but it acts as a reservoir, being able to enter into the proximal intestine and cross the intestinal barrier.10 Secondly, the above fact could also constitute a long-term defecation reservoir, making it easier for the germ to spread, with resulting significant implications in the public health sector, as is the case with Salmonella typhimurium. This has only been able to be confirmed with studies in mice.8,10 Finally, the presence of cholelithiasis and/or choledocolithiasis and the bile duct obstruction in a patient with a prior LM colonisation could trigger symptoms of cholangitis or acute cholecystitis,8–10 as happened in the case that we described in this paper.

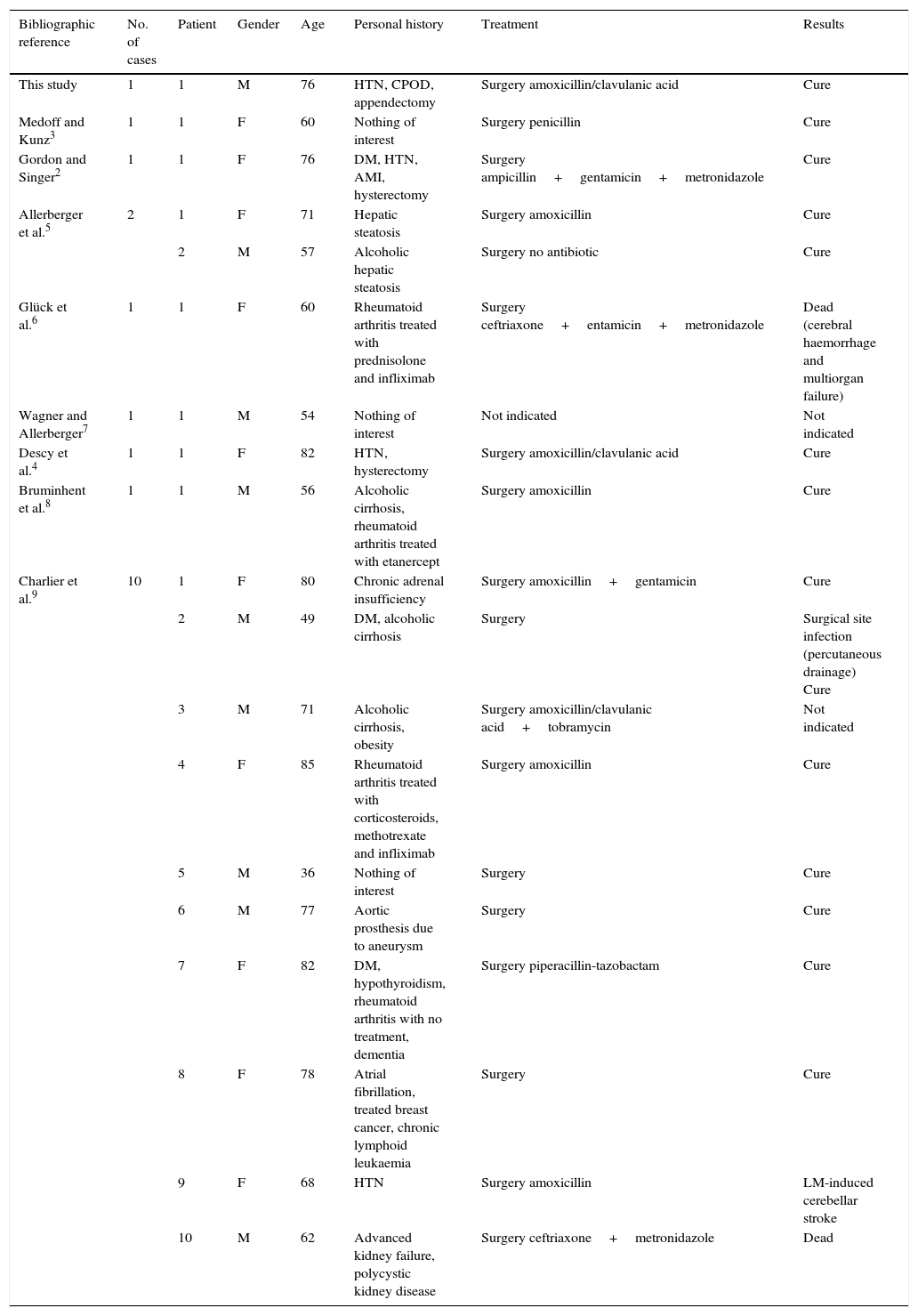

LM is a germ that in recent years has been attracting more attention due to its role in food poisoning, manifesting itself with gastroenteritis symptoms on most occasions. It was able to systemic involvement in patients changes in cell immunity, and especially so in patients receiving treatment with tumour necrosis factor inhibitors where LM can cause morbimortality.6,8,9 Unlike most of the few published cases in the literature, our case presents the characteristic of being an immunocompetent patient, who does not take immunosuppressive medication, although it is an elderly patient with associated chronic diseases (Table 1).

Published papers in the literature about acute Listeria monocytogenes-induced cholecystitis.

| Bibliographic reference | No. of cases | Patient | Gender | Age | Personal history | Treatment | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| This study | 1 | 1 | M | 76 | HTN, CPOD, appendectomy | Surgery amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Cure |

| Medoff and Kunz3 | 1 | 1 | F | 60 | Nothing of interest | Surgery penicillin | Cure |

| Gordon and Singer2 | 1 | 1 | F | 76 | DM, HTN, AMI, hysterectomy | Surgery ampicillin+gentamicin+metronidazole | Cure |

| Allerberger et al.5 | 2 | 1 | F | 71 | Hepatic steatosis | Surgery amoxicillin | Cure |

| 2 | M | 57 | Alcoholic hepatic steatosis | Surgery no antibiotic | Cure | ||

| Glück et al.6 | 1 | 1 | F | 60 | Rheumatoid arthritis treated with prednisolone and infliximab | Surgery ceftriaxone+entamicin+metronidazole | Dead (cerebral haemorrhage and multiorgan failure) |

| Wagner and Allerberger7 | 1 | 1 | M | 54 | Nothing of interest | Not indicated | Not indicated |

| Descy et al.4 | 1 | 1 | F | 82 | HTN, hysterectomy | Surgery amoxicillin/clavulanic acid | Cure |

| Bruminhent et al.8 | 1 | 1 | M | 56 | Alcoholic cirrhosis, rheumatoid arthritis treated with etanercept | Surgery amoxicillin | Cure |

| Charlier et al.9 | 10 | 1 | F | 80 | Chronic adrenal insufficiency | Surgery amoxicillin+gentamicin | Cure |

| 2 | M | 49 | DM, alcoholic cirrhosis | Surgery | Surgical site infection (percutaneous drainage) Cure | ||

| 3 | M | 71 | Alcoholic cirrhosis, obesity | Surgery amoxicillin/clavulanic acid+tobramycin | Not indicated | ||

| 4 | F | 85 | Rheumatoid arthritis treated with corticosteroids, methotrexate and infliximab | Surgery amoxicillin | Cure | ||

| 5 | M | 36 | Nothing of interest | Surgery | Cure | ||

| 6 | M | 77 | Aortic prosthesis due to aneurysm | Surgery | Cure | ||

| 7 | F | 82 | DM, hypothyroidism, rheumatoid arthritis with no treatment, dementia | Surgery piperacillin-tazobactam | Cure | ||

| 8 | F | 78 | Atrial fibrillation, treated breast cancer, chronic lymphoid leukaemia | Surgery | Cure | ||

| 9 | F | 68 | HTN | Surgery amoxicillin | LM-induced cerebellar stroke | ||

| 10 | M | 62 | Advanced kidney failure, polycystic kidney disease | Surgery ceftriaxone+metronidazole | Dead |

AMI, acute myocardial infarction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; DM, diabetes mellitus; HTN, hypertension.

After surgery, there is no evidence of the need of an antibiotic treatment for cases of uncomplicated cholecystitis caused by the typical germs. Although, the majority of the patients that are hospitalised with this disease usually receive it.8 In bile tract infections, the clinical guidelines recommend agents such as cefazolin, ceftriaxone, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin and vancomycin, alone or in combination with metronidazole.1,8 Resistance to these agents has been found in LM, with the exception of cefazolin and vancomycin.8 Although, ampicillin and penicillin are the antibiotics of choice for LM due to their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and the risk of central nervous system involvement.8 Adding aminoglycosides is recommended in cases of severe infection.8 Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole is considered the best alternative in cases of penicillin allergies.8

In conclusion, we could confirm that the LM-induced bile duct infection must be considered as an uncommon cause of cholecystitis, not just the asymptomatic or transitory bile colonisation, which should be taken into consideration by physicians. LM-induced cholecystitis must be treated surgically with cholecystectomy, and adding an antibiotic treatment, mainly ampicillin or amoxicillin, must be proposed in those cases that present an added risk of systemic complications, mainly in immunocompromised patients.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Palomeque Jiménez A, Rubio López A, Jiménez Ríos JA, Pérez Cabrera B. Colecistitis aguda por Listeria monocytogenes en paciente inmunocompetente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:31–33.