Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease of the digestive tract and up to 20–30% of UC patients may suffer a severe flare-up during the course of the disease. Although there are national and international recommendations about its clinical management, there is not enough information about the treatment of acute severe UC in clinical practice.

MethodsAn electronic and anonymous survey with 51 multiple-choice questions was performed among all the members of the Spanish Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Working Group (GETECCU).

ResultsOut of the 164 responders (20%), most were gastroenterologists (95%), with 59% from tertiary hospitals treating a median of 5 patients per year (IQR: 3–8) with a severe flare-up of ulcerative colitis. An endoscopic examination was routinely performed in 86% of patients (62% at admission). The most commonly used corticosteroid was methylprednisolone, usually at a dose of 60mg/day, and its response was assessed after a median of 3 days (IQR: 3–5). Both in thiopurine-naïve and thiopurine-refractory patients, infliximab was the drug most frequently prescribed as rescue therapy. Half of responders (55%) had ever prescribed a first dose of infliximab higher than 5mg/kg, and a higher proportion (73%) had ever prescribed an earlier dose of infliximab in the second or third infusion.

ConclusionsAcute severe UC is generally managed according to current treatment guidelines in our setting. The rescue therapy most commonly prescribed is infliximab, and the use of intensified or accelerated regimens with this biological drug is not unusual.

La colitis ulcerosa es una enfermedad crónica del tracto digestivo, y hasta el 20-30% de los pacientes sufren un brote grave durante su evolución. Aunque existen guías nacionales e internacionales sobre el tratamiento de la colitis ulcerosa aguda grave, desconocemos cómo se manejan en la práctica clínica estos pacientes en nuestro medio.

MétodosRealizamos una encuesta electrónica y anónima entre los miembros del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU), compuesta por 51 preguntas con respuestas predefinidas.

ResultadosParticiparon 164 miembros (20%), en su mayoría especialistas de aparato digestivo (95%). El 59% trabajaban en hospitales terciarios, atendiendo a una mediana de 5 pacientes al año (RIC: 3-8) con un brote grave de colitis ulcerosa. El 86% realizan un estudio endoscópico rutinario, habitualmente al ingreso (62%). El corticoide más empleado es la metilprednisolona, habitualmente a una dosis de 60mg/día, y se evalúa su respuesta pasados 3días (mediana, RIC: 3-5). El tratamiento de rescate usado con más frecuencia es infliximab, tanto en pacientes naïve como refractarios a tiopurinas. El 55% han indicado en alguna ocasión una dosis de infliximab mayor de 5mg/kg durante la inducción, y el 73% han adelantado alguna de las sucesivas infusiones.

ConclusionesEl manejo de la colitis ulcerosa aguda grave en nuestro entorno se ajusta en general a las recomendaciones de tratamiento actuales. El tratamiento de rescate más frecuentemente prescrito es el infliximab, y no es excepcional el empleo de pautas intensificadas o aceleradas de este biológico.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic disease affecting the colon which usually involves flare-ups with symptoms such as diarrhoea and rectal bleeding.1 Among patients with UC, 20–30% can suffer a serious flare-up (severe acute ulcerative colitis [ASUC]) requiring hospital admission.2 The diagnosis of ASUC is based on the classic Truelove and Witts criteria, which require ≥six stools with blood a day plus any of the following: heart rate >90bpm; body temperature >37.8°C; haemoglobin <10.5g/dl; and erythrocyte sedimentation rate >30mm/h.3 Before the introduction of intravenous corticosteroid treatment and emergency colectomy, ASUC was associated with a mortality rate of 70%, but the rate has decreased dramatically in recent years and is now below 1%.4 The keys to management of ASUC are based on early diagnosis, admission to hospital and the introduction without delay of medical treatment with intravenous corticosteroids. Despite these measures, 30–40% of patients do not improve and require other medical treatment alternatives or surgery.5

There is still a lack of consensus over some aspects of ASUC, but recent guidelines and recommendations are available that set out how these patients should be managed.6–8 However, we lack information on the actual usual clinical practice in our region. The aim of this study was to assess the fundamental aspects of the management of ASUC in clinical practice in our environment.

MethodsWe designed an electronic survey containing 51 questions covering the most important aspects of the management of ASUC. The surveyed population consisted of the entire membership of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis], which at the time of the survey consisted of 810 people. The project followed the usual review process established in GETECCU, being completed with approval of the final version of the survey. The questions were designed to analyse the usual patterns of initial medical treatment with corticosteroids and aminosalicylates, active search for some infections such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), prophylaxis and treatment of other infections, the endoscopic examinations performed, the patterns of use of the different rescue treatments available and how assessment for surgery was carried out in this situation.

Three invitations were sent out by email from February to April 2018. The survey was designed through the electronic platform REDCap, provided by the Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastroenterology].9 The AEG is a non-profit scientific association that provides this service free of charge with the aim of promoting multicentre research sponsored by independent researchers. The REDCap platform is a web application designed to collect information for research studies consisting of an intuitive interface, with tools for data monitoring and export to the main statistical programs, as well as the ability to import data from other sources. The survey was designed on this platform and was completed anonymously in all cases.

Out of a total of 810 members, taking into account 15% losses due to errors in the delivery or receipt of the invitations, and with an estimated participation of 20%, the expected number of responses was 137. The results were entered into an electronic database, where the statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS program version 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). For quantitative variables, mean and standard deviation were calculated if they had a normal distribution, or median and interquartile range (IQR) otherwise. The responses were compared using the chi-square statistical test (χ2). Differences with a p value below 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

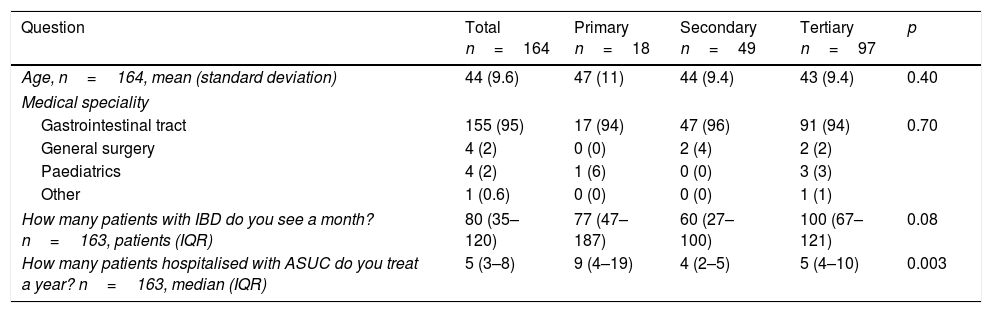

ResultsA total of 164 members participated (20% of the total). The results of all the responses relating to demographic aspects are shown in Table 1. The participants had a mean age of 44 (standard deviation: 9.6). In 95% of cases they were specialists in gastroenterology and 59% of the total worked in tertiary hospitals. They stated that they saw approximately 80 patients (IQR: 35–120) with inflammatory bowel disease a month. In addition, each year they treated a median of five patients (IQR: 3–8) with a flare-up of ASUC.

Epidemiological aspects.

| Question | Total n=164 | Primary n=18 | Secondary n=49 | Tertiary n=97 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, n=164, mean (standard deviation) | 44 (9.6) | 47 (11) | 44 (9.4) | 43 (9.4) | 0.40 |

| Medical speciality | |||||

| Gastrointestinal tract | 155 (95) | 17 (94) | 47 (96) | 91 (94) | 0.70 |

| General surgery | 4 (2) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 2 (2) | |

| Paediatrics | 4 (2) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |

| Other | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| How many patients with IBD do you see a month? n=163, patients (IQR) | 80 (35–120) | 77 (47–187) | 60 (27–100) | 100 (67–121) | 0.08 |

| How many patients hospitalised with ASUC do you treat a year? n=163, median (IQR) | 5 (3–8) | 9 (4–19) | 4 (2–5) | 5 (4–10) | 0.003 |

ASUC: acute severe ulcerative colitis; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; IQR: interquartile range.

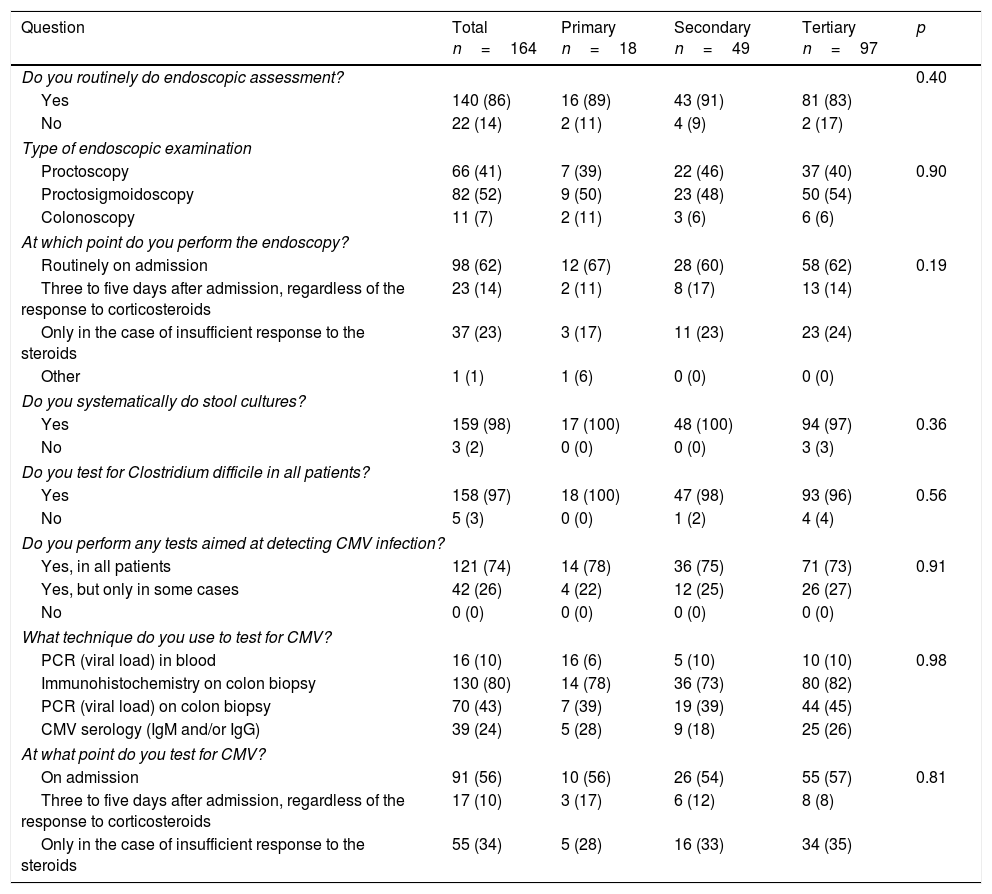

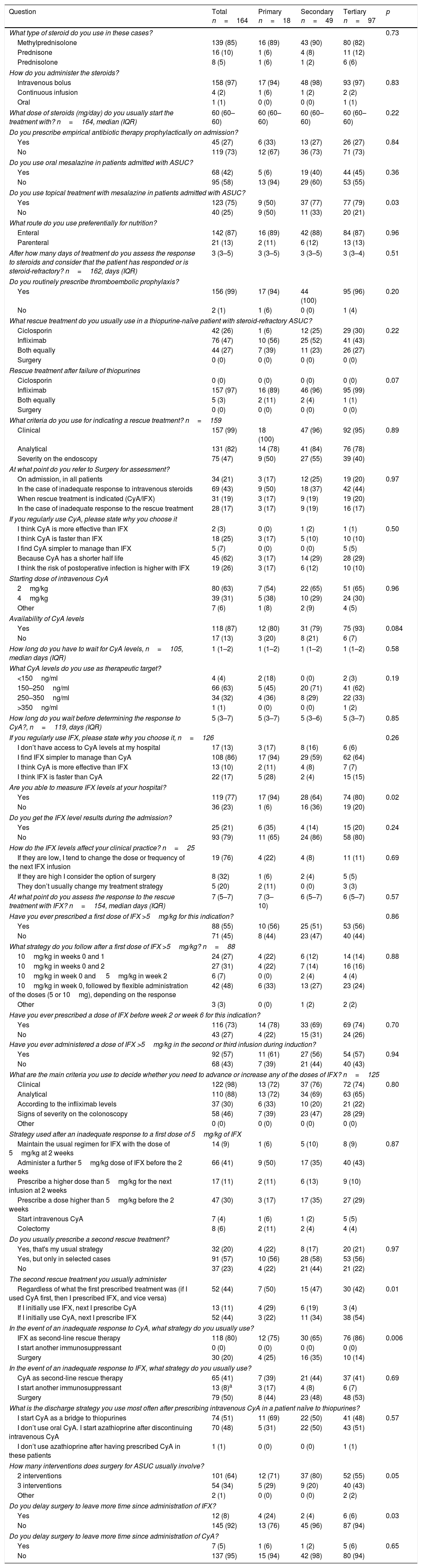

The results from the questions relating to diagnostic aspects are shown in Table 2, and those relating to treatment in Table 3. A total of 98% of participants ordered a stool culture and 97% a determination of Clostridium difficile toxin on admission; 99% administered thromboembolic prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin; and 27% prescribed empirical antibiotic therapy. Testing for CMV infection was performed routinely by 74% of the participants, often on admission (56%) or in the case of an inadequate response to corticosteroids (34%). The technique most used to test for CMV was immunohistochemistry (80%) and, less frequently, PCR on colon biopsy (43%). Endoscopy was performed routinely by 86%, on admission in 62% of cases. The most common examination performed was proctosigmoidoscopy (52%), followed by proctoscopy (41%), while 7% performed colonoscopy. For the initial treatment with corticosteroids in these cases, the majority of participants chose methylprednisolone (85%) at a dose of 60mg/day administered by intravenous bolus injections (97%).

Diagnosis.

| Question | Total n=164 | Primary n=18 | Secondary n=49 | Tertiary n=97 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Do you routinely do endoscopic assessment? | 0.40 | ||||

| Yes | 140 (86) | 16 (89) | 43 (91) | 81 (83) | |

| No | 22 (14) | 2 (11) | 4 (9) | 2 (17) | |

| Type of endoscopic examination | |||||

| Proctoscopy | 66 (41) | 7 (39) | 22 (46) | 37 (40) | 0.90 |

| Proctosigmoidoscopy | 82 (52) | 9 (50) | 23 (48) | 50 (54) | |

| Colonoscopy | 11 (7) | 2 (11) | 3 (6) | 6 (6) | |

| At which point do you perform the endoscopy? | |||||

| Routinely on admission | 98 (62) | 12 (67) | 28 (60) | 58 (62) | 0.19 |

| Three to five days after admission, regardless of the response to corticosteroids | 23 (14) | 2 (11) | 8 (17) | 13 (14) | |

| Only in the case of insufficient response to the steroids | 37 (23) | 3 (17) | 11 (23) | 23 (24) | |

| Other | 1 (1) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Do you systematically do stool cultures? | |||||

| Yes | 159 (98) | 17 (100) | 48 (100) | 94 (97) | 0.36 |

| No | 3 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |

| Do you test for Clostridium difficile in all patients? | |||||

| Yes | 158 (97) | 18 (100) | 47 (98) | 93 (96) | 0.56 |

| No | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 4 (4) | |

| Do you perform any tests aimed at detecting CMV infection? | |||||

| Yes, in all patients | 121 (74) | 14 (78) | 36 (75) | 71 (73) | 0.91 |

| Yes, but only in some cases | 42 (26) | 4 (22) | 12 (25) | 26 (27) | |

| No | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| What technique do you use to test for CMV? | |||||

| PCR (viral load) in blood | 16 (10) | 16 (6) | 5 (10) | 10 (10) | 0.98 |

| Immunohistochemistry on colon biopsy | 130 (80) | 14 (78) | 36 (73) | 80 (82) | |

| PCR (viral load) on colon biopsy | 70 (43) | 7 (39) | 19 (39) | 44 (45) | |

| CMV serology (IgM and/or IgG) | 39 (24) | 5 (28) | 9 (18) | 25 (26) | |

| At what point do you test for CMV? | |||||

| On admission | 91 (56) | 10 (56) | 26 (54) | 55 (57) | 0.81 |

| Three to five days after admission, regardless of the response to corticosteroids | 17 (10) | 3 (17) | 6 (12) | 8 (8) | |

| Only in the case of insufficient response to the steroids | 55 (34) | 5 (28) | 16 (33) | 34 (35) | |

CMV: cytomegalovirus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction.

Results expressed as frequency (%).

Treatment.

| Question | Total n=164 | Primary n=18 | Secondary n=49 | Tertiary n=97 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| What type of steroid do you use in these cases? | 0.73 | ||||

| Methylprednisolone | 139 (85) | 16 (89) | 43 (90) | 80 (82) | |

| Prednisone | 16 (10) | 1 (6) | 4 (8) | 11 (12) | |

| Prednisolone | 8 (5) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 6 (6) | |

| How do you administer the steroids? | |||||

| Intravenous bolus | 158 (97) | 17 (94) | 48 (98) | 93 (97) | 0.83 |

| Continuous infusion | 4 (2) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Oral | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| What dose of steroids (mg/day) do you usually start the treatment with? n=164, median (IQR) | 60 (60–60) | 60 (60–60) | 60 (60–60) | 60 (60–60) | 0.22 |

| Do you prescribe empirical antibiotic therapy prophylactically on admission? | |||||

| Yes | 45 (27) | 6 (33) | 13 (27) | 26 (27) | 0.84 |

| No | 119 (73) | 12 (67) | 36 (73) | 71 (73) | |

| Do you use oral mesalazine in patients admitted with ASUC? | |||||

| Yes | 68 (42) | 5 (6) | 19 (40) | 44 (45) | 0.36 |

| No | 95 (58) | 13 (94) | 29 (60) | 53 (55) | |

| Do you use topical treatment with mesalazine in patients admitted with ASUC? | |||||

| Yes | 123 (75) | 9 (50) | 37 (77) | 77 (79) | 0.03 |

| No | 40 (25) | 9 (50) | 11 (33) | 20 (21) | |

| What route do you use preferentially for nutrition? | |||||

| Enteral | 142 (87) | 16 (89) | 42 (88) | 84 (87) | 0.96 |

| Parenteral | 21 (13) | 2 (11) | 6 (12) | 13 (13) | |

| After how many days of treatment do you assess the response to steroids and consider that the patient has responded or is steroid-refractory? n=162, days (IQR) | 3 (3–5) | 3 (3–5) | 3 (3–5) | 3 (3–4) | 0.51 |

| Do you routinely prescribe thromboembolic prophylaxis? | |||||

| Yes | 156 (99) | 17 (94) | 44 (100) | 95 (96) | 0.20 |

| No | 2 (1) | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (4) | |

| What rescue treatment do you usually use in a thiopurine-naïve patient with steroid-refractory ASUC? | |||||

| Ciclosporin | 42 (26) | 1 (6) | 12 (25) | 29 (30) | 0.22 |

| Infliximab | 76 (47) | 10 (56) | 25 (52) | 41 (43) | |

| Both equally | 44 (27) | 7 (39) | 11 (23) | 26 (27) | |

| Surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Rescue treatment after failure of thiopurines | |||||

| Ciclosporin | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.07 |

| Infliximab | 157 (97) | 16 (89) | 46 (96) | 95 (99) | |

| Both equally | 5 (3) | 2 (11) | 2 (4) | 1 (1) | |

| Surgery | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| What criteria do you use for indicating a rescue treatment? n=159 | |||||

| Clinical | 157 (99) | 18 (100) | 47 (96) | 92 (95) | 0.89 |

| Analytical | 131 (82) | 14 (78) | 41 (84) | 76 (78) | |

| Severity on the endoscopy | 75 (47) | 9 (50) | 27 (55) | 39 (40) | |

| At what point do you refer to Surgery for assessment? | |||||

| On admission, in all patients | 34 (21) | 3 (17) | 12 (25) | 19 (20) | 0.97 |

| In the case of inadequate response to intravenous steroids | 69 (43) | 9 (50) | 18 (37) | 42 (44) | |

| When rescue treatment is indicated (CyA/IFX) | 31 (19) | 3 (17) | 9 (19) | 19 (20) | |

| In the case of inadequate response to the rescue treatment | 28 (17) | 3 (17) | 9 (19) | 16 (17) | |

| If you regularly use CyA, please state why you choose it | |||||

| I think CyA is more effective than IFX | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 0.50 |

| I think CyA is faster than IFX | 18 (25) | 3 (17) | 5 (10) | 10 (10) | |

| I find CyA simpler to manage than IFX | 5 (7) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (5) | |

| Because CyA has a shorter half life | 45 (62) | 3 (17) | 14 (29) | 28 (29) | |

| I think the risk of postoperative infection is higher with IFX | 19 (26) | 3 (17) | 6 (12) | 10 (10) | |

| Starting dose of intravenous CyA | |||||

| 2mg/kg | 80 (63) | 7 (54) | 22 (65) | 51 (65) | 0.96 |

| 4mg/kg | 39 (31) | 5 (38) | 10 (29) | 24 (30) | |

| Other | 7 (6) | 1 (8) | 2 (9) | 4 (5) | |

| Availability of CyA levels | |||||

| Yes | 118 (87) | 12 (80) | 31 (79) | 75 (93) | 0.084 |

| No | 17 (13) | 3 (20) | 8 (21) | 6 (7) | |

| How long do you have to wait for CyA levels, n=105, median days (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–2) | 0.58 |

| What CyA levels do you use as therapeutic target? | |||||

| <150ng/ml | 4 (4) | 2 (18) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 0.19 |

| 150–250ng/ml | 66 (63) | 5 (45) | 20 (71) | 41 (62) | |

| 250–350ng/ml | 34 (32) | 4 (36) | 8 (29) | 22 (33) | |

| >350ng/ml | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | |

| How long do you wait before determining the response to CyA?, n=119, days (IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–7) | 5 (3–6) | 5 (3–7) | 0.85 |

| If you regularly use IFX, please state why you choose it, n=126 | 0.26 | ||||

| I don’t have access to CyA levels at my hospital | 17 (13) | 3 (17) | 8 (16) | 6 (6) | |

| I find IFX simpler to manage than CyA | 108 (86) | 17 (94) | 29 (59) | 62 (64) | |

| I think CyA is more effective than IFX | 13 (10) | 2 (11) | 4 (8) | 7 (7) | |

| I think IFX is faster than CyA | 22 (17) | 5 (28) | 2 (4) | 15 (15) | |

| Are you able to measure IFX levels at your hospital? | |||||

| Yes | 119 (77) | 17 (94) | 28 (64) | 74 (80) | 0.02 |

| No | 36 (23) | 1 (6) | 16 (36) | 19 (20) | |

| Do you get the IFX level results during the admission? | |||||

| Yes | 25 (21) | 6 (35) | 4 (14) | 15 (20) | 0.24 |

| No | 93 (79) | 11 (65) | 24 (86) | 58 (80) | |

| How do the IFX levels affect your clinical practice? n=25 | |||||

| If they are low, I tend to change the dose or frequency of the next IFX infusion | 19 (76) | 4 (22) | 4 (8) | 11 (11) | 0.69 |

| If they are high I consider the option of surgery | 8 (32) | 1 (6) | 2 (4) | 5 (5) | |

| They don’t usually change my treatment strategy | 5 (20) | 2 (11) | 0 (0) | 3 (3) | |

| At what point do you assess the response to the rescue treatment with IFX? n=154, median days (IQR) | 7 (5–7) | 7 (3–10) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) | 0.57 |

| Have you ever prescribed a first dose of IFX >5mg/kg for this indication? | 0.86 | ||||

| Yes | 88 (55) | 10 (56) | 25 (51) | 53 (56) | |

| No | 71 (45) | 8 (44) | 23 (47) | 40 (44) | |

| What strategy do you follow after a first dose of IFX >5mg/kg? n=88 | |||||

| 10mg/kg in weeks 0 and 1 | 24 (27) | 4 (22) | 6 (12) | 14 (14) | 0.88 |

| 10mg/kg in weeks 0 and 2 | 27 (31) | 4 (22) | 7 (14) | 16 (16) | |

| 10mg/kg in week 0 and 5mg/kg in week 2 | 6 (7) | 0 (0) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | |

| 10mg/kg in week 0, followed by flexible administration of the doses (5 or 10mg), depending on the response | 42 (48) | 6 (33) | 13 (27) | 23 (24) | |

| Other | 3 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) | 2 (2) | |

| Have you ever prescribed a dose of IFX before week 2 or week 6 for this indication? | |||||

| Yes | 116 (73) | 14 (78) | 33 (69) | 69 (74) | 0.70 |

| No | 43 (27) | 4 (22) | 15 (31) | 24 (26) | |

| Have you ever administered a dose of IFX >5mg/kg in the second or third infusion during induction? | |||||

| Yes | 92 (57) | 11 (61) | 27 (56) | 54 (57) | 0.94 |

| No | 68 (43) | 7 (39) | 21 (44) | 40 (43) | |

| What are the main criteria you use to decide whether you need to advance or increase any of the doses of IFX? n=125 | |||||

| Clinical | 122 (98) | 13 (72) | 37 (76) | 72 (74) | 0.80 |

| Analytical | 110 (88) | 13 (72) | 34 (69) | 63 (65) | |

| According to the infliximab levels | 37 (30) | 6 (33) | 10 (20) | 21 (22) | |

| Signs of severity on the colonoscopy | 58 (46) | 7 (39) | 23 (47) | 28 (29) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Strategy used after an inadequate response to a first dose of 5mg/kg of IFX | |||||

| Maintain the usual regimen for IFX with the dose of 5mg/kg at 2 weeks | 14 (9) | 1 (6) | 5 (10) | 8 (9) | 0.87 |

| Administer a further 5mg/kg dose of IFX before the 2 weeks | 66 (41) | 9 (50) | 17 (35) | 40 (43) | |

| Prescribe a higher dose than 5mg/kg for the next infusion at 2 weeks | 17 (11) | 2 (11) | 6 (13) | 9 (10) | |

| Prescribe a dose higher than 5mg/kg before the 2 weeks | 47 (30) | 3 (17) | 17 (35) | 27 (29) | |

| Start intravenous CyA | 7 (4) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 5 (5) | |

| Colectomy | 8 (6) | 2 (11) | 2 (4) | 4 (4) | |

| Do you usually prescribe a second rescue treatment? | |||||

| Yes, that's my usual strategy | 32 (20) | 4 (22) | 8 (17) | 20 (21) | 0.97 |

| Yes, but only in selected cases | 91 (57) | 10 (56) | 28 (58) | 53 (56) | |

| No | 37 (23) | 4 (22) | 21 (44) | 21 (22) | |

| The second rescue treatment you usually administer | |||||

| Regardless of what the first prescribed treatment was (if I used CyA first, then I prescribed IFX, and vice versa) | 52 (44) | 7 (50) | 15 (47) | 30 (42) | 0.01 |

| If I initially use IFX, next I prescribe CyA | 13 (11) | 4 (29) | 6 (19) | 3 (4) | |

| If I initially use CyA, next I prescribe IFX | 52 (44) | 3 (22) | 11 (34) | 38 (54) | |

| In the event of an inadequate response to CyA, what strategy do you usually use? | |||||

| IFX as second-line rescue therapy | 118 (80) | 12 (75) | 30 (65) | 76 (86) | 0.006 |

| I start another immunosuppressant | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Surgery | 30 (20) | 4 (25) | 16 (35) | 10 (14) | |

| In the event of an inadequate response to IFX, what strategy do you usually use? | |||||

| CyA as second-line rescue therapy | 65 (41) | 7 (39) | 21 (44) | 37 (41) | 0.69 |

| I start another immunosuppressant | 13 (8)a | 3 (17) | 4 (8) | 6 (7) | |

| Surgery | 79 (50) | 8 (44) | 23 (48) | 48 (53) | |

| What is the discharge strategy you use most often after prescribing intravenous CyA in a patient naïve to thiopurines? | |||||

| I start CyA as a bridge to thiopurines | 74 (51) | 11 (69) | 22 (50) | 41 (48) | 0.57 |

| I don’t use oral CyA. I start azathioprine after discontinuing intravenous CyA | 70 (48) | 5 (31) | 22 (50) | 43 (51) | |

| I don’t use azathioprine after having prescribed CyA in these patients | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | |

| How many interventions does surgery for ASUC usually involve? | |||||

| 2 interventions | 101 (64) | 12 (71) | 37 (80) | 52 (55) | 0.05 |

| 3 interventions | 54 (34) | 5 (29) | 9 (20) | 40 (43) | |

| Other | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | |

| Do you delay surgery to leave more time since administration of IFX? | |||||

| Yes | 12 (8) | 4 (24) | 2 (4) | 6 (6) | 0.03 |

| No | 145 (92) | 13 (76) | 45 (96) | 87 (94) | |

| Do you delay surgery to leave more time since administration of CyA? | |||||

| Yes | 7 (5) | 1 (6) | 1 (2) | 5 (6) | 0.65 |

| No | 137 (95) | 15 (94) | 42 (98) | 80 (94) | |

CyA: ciclosporin; ASUC: acute severe ulcerative colitis; IFX: infliximab; IQR: interquartile range.

We found that the response to corticosteroids was assessed after three days of treatment and that this was consistent across the different types of hospitals studied (IQR: 3–5); 66% of the members analysed the response to intravenous corticosteroids after three days of treatment. In patients who do not respond to corticosteroid treatment and who have not received treatment with thiopurines, 47% of the respondents said they usually started infliximab (IFX) and 26% ciclosporin (CyA), while 27% had no preference for either of the two drugs. In patients suffering from a flare-up of ASUC and already on treatment with thiopurines, the physicians surveyed used IFX in most cases (97%), while 3% were indifferent about using IFX or CyA. When CyA is used, it is most often chosen because of its shorter half-life (62%) or its faster mechanism of action (25%). The initial CyA dose was usually 2mg/kg (63% of the participants). Among the participants who most frequently used IFX, it was chosen primarily for its ease of use (86%). The determination of IFX levels was available in 77% of the hospitals, but despite that, the results were not usually available during the time the patient was in hospital for the ASUC flare-up (79% of the cases).

Approximately half of the respondents (55%) had used an initial dose of IFX higher than 5mg/kg at some point. Among those who had done so, the previous strategy was most often followed by flexible administration of the doses (5 or 10mg/kg) for the second infusion, depending on the response (48%). A proportion similar to that observed with the initial dose (57%) had at some point used a higher dose of IFX (>5mg/kg) in the second or third infusion. When the therapeutic objectives were not achieved with IFX, 41% of the participants brought forward the second or third dose of IFX, while a third had brought forward a dose and administered higher doses during the induction period.

Overall, 20% of the participants used a second rescue treatment (IFX after the failure of CyA, or vice versa) on a routine basis, while 23% never did so. More respondents preferred to use IFX after CyA than vice versa (44% vs 11%), although 44% used a second rescue treatment regardless of the first drug prescribed. Among participants who routinely used IFX, after an inadequate response, they usually indicated surgery (50%) or CyA (41%).

SurgeryIn most cases, assessment by a surgeon was requested once it was decided that the ASUC flare-up was steroid refractory (43%) and less often routinely on admission (21%). Surgery was usually performed in two interventions (64%), and the previous administration of IFX (92%) or CyA (95%) did not affect the timing of the intervention.

Results according to the type of hospitalThe results of the survey are shown in Tables 1–3 divided by the type of hospital the respondents were working at. As the figures show, the participants who worked at primary-level hospitals dealt with a slightly larger number of cases of ASUC (p=0.003). For rescue treatment in thiopurine-naïve patients, CyA was used more frequently in tertiary hospitals, while IFX was used with a slightly higher frequency in primary or secondary level hospitals, although these differences were not statistically significant (p=0.22). In cases refractory to thiopurines, the use of IFX was the most common approach, with no differences found according to the type of hospital (p=0.07). Although the differences were not statistically significant (p=0.19), a slightly higher proportion of participants from primary-level hospitals had target levels of CyA of <150ng/ml, compared to those in secondary or tertiary level hospitals (18% vs 0% and 3% respectively). We found that accelerated or intensified IFX regimens were used with the same frequency regardless of the type of hospital, and that the strategy in the subsequent regimens during induction was also similar. Although the extent of use of a second rescue treatment was similar in the groups analysed, in the tertiary hospitals, IFX after CyA was most common for rescue treatment, whereas in the primary or secondary level hospitals, the reverse order was more commonly used (p=0.01).

DiscussionASUC is a complication with high morbidity and mortality rates which, in our environment, is generally managed in accordance with current clinical practice recommendations.6–8 However, as the results of this survey suggest, there is still a great deal of variation in the management of ASUC in routine practice. In steroid-refractory ASUC, IFX is the most commonly used option, over and above CyA. In addition, up to half of the respondents use an IFX regimen with intensified or accelerated dosing strategies.

The disease course of UC in terms of clinical activity was recently analysed in a systematic review.10 The authors found that the majority of patients with UC have mild-to-moderate clinical activity, with the predominance of activity closest to the time of diagnosis. In any event, it must be borne in mind that over the course of the disease 20–30% of patients require hospitalisation for a serious flare-up.2 Moreover, in general, the risk of suffering from new flare-ups beyond 10 years post-diagnosis is 70–80%, and the risk of hospitalisation is 50%. Another very relevant aspect clinically is that 10–15% of patients will require a colectomy 5–10 years after diagnosis.

A survey was recently conducted in the United States by the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of the American Clinical Research Alliance and active members of the International Organisation for Inflammatory Bowel Disease with the aim of assessing the use of modified IFX regimens.11 In that survey, it was found that only 24% of physicians used the usual doses of IFX during induction in patients with ASUC (5mg/kg at weeks 0, 2, and 6). The most commonly used criteria for deciding the use of an accelerated IFX regimen were based on symptoms, C-reactive protein and IFX levels. In patients in whom the administration of the drug was brought forward, this decision was based on clinical severity (68%), but in other cases (22%) it was made taking C-reactive protein, albumin and severity of endoscopic lesions into account. Among the different strategies used, 25% of the respondents used an initial dose of 5mg/kg followed by a dose of 10mg/kg in week two if the response was unsatisfactory. The second most common strategy (18%) was the use of 10mg/kg from the start, with flexible administration of the doses.

In our setting, among the members of GETECCU, the management of ASUC flare-ups is generally in line with current recommendations on the management of such cases in clinical practice.6–8 We can see that these specialists, the majority gastroenterologists, see a large number of outpatients with inflammatory bowel disease, although the cases of ASUC remain consistent at approximately five a year. One of the most fundamental aspects is the establishment of clear therapeutic targets, especially in the first three to five days of corticosteroid treatment. We were able to confirm that in our setting, and in the different types of hospitals analysed, the period for considering a patient as steroid refractory conforms to international recommendations.6–8 Other important aspects, such as stool cultures and the determination of C. difficile toxin, are generalised, although 2–3% of the participants do not perform them routinely. It is worth noting that neither endoscopic examination nor testing for CMV infection are carried out systematically (86% and 74% respectively), despite the fact that recommendations state they should be assessed in this situation.6,12 Among the respondents who test for CMV infection, the analysis is usually requested on admission (56%), although a significant proportion of respondents only test for it in the case of an inadequate response to corticosteroids (34%). This aspect is important in routine practice, as it was recently found that there is no association between treatment with IFX or CyA in patients with active UC hospitalised for a moderate/severe flare-up who are being treated for CMV infection and a higher rate of colectomy.13 As part of the general management of the cases of ASUC, we also found that the use of mesalazine, both oral (42%) and topical (75%), is relatively common, even though there is no clear evidence for its use in this context.

We found in this survey that the rescue treatment most used in ASUC is IFX, regardless of whether the patients are receiving azathioprine at the time of the flare-up. An additional aspect that we assessed is the use of different-from-the-usual IFX regimens, as it has been suggested that these patients may need a different dosing strategy because of the particular pathophysiology of ASUC.14 In these cases, in addition to a greater clearance of the drug, aided by the higher systemic inflammatory load, there may be an increase in intestinal permeability, leading to a loss of drug in the faeces.15–17 For that reason, it has been suggested that in certain situations, it may be necessary to modify the usual IFX regimen, either by reducing the interval between doses (accelerated regimen) or increasing the dose of each infusion (intensified regimen).14 Few studies have assessed the use of accelerated or intensified IFX regimens. The evidence on doses, administration intervals and management decisions is therefore still very limited and is not included in the main guidelines on the management of IFX in this disease. In the principal study that has been conducted in this area, the administration of three doses of IFX within a 24-day period (IQR: 21–29) was associated with a lower risk of colectomy at three months compared to the usual IFX regimen.18 Other studies did not find any clear differences in the rate of colectomy after three and 12 months with administration of a 20-day accelerated induction regimen (IQR: 1–26).19 In our setting, according to the results of the survey, approximately half of the specialists have at some point used a higher than usual dose (intensified regimen) during induction in these patients. In cases where therapeutic targets are not achieved with a first infusion of 5mg/kg, a significant proportion of the respondents (82%) has used a second or third modified dose of IFX. A second rescue treatment is routinely used by 20%, while the majority (57%) only prescribe it in selected cases. Among the participants of the survey we found this strategy to be more common when the first drug used was CyA. Although we did not assess the time interval between the two medications in our survey, in the literature, the median interval ranges from 2 to 19 days, whereas if the first drug was IFX the interval was from 19 to 21 days.20

There are two main limitations to the results of our study. On the one hand, the limited participation in the survey (20%) affects generalisation of the data to routine clinical practice. Moreover, it is possible that the participants had a greater interest in or knowledge of the subject and this could lead to better results than in real life. On the other hand, certain variables analysed were obtained directly from the participants, without seeking objective data on aspects such as the number of patients treated, the dose of the drugs or the timing of assessing response to corticosteroids. This has to be taken into account, as we are relying on participants’ memories of these aspects and that may add bias to our results.

A recent study, also conducted by GETECCU, found that the mortality rate in cases of ASUC varied according to the type of hospital analysed.21 There was also an association between death and other factors such as age, the extent of the disease, emergency surgery and complications.21 In our survey we analysed the results according to the type of hospital where the participants worked, and did not find significant differences in the management of these patients. This shows that clinical practice in our environment is homogeneous in this context. An interesting finding was the trend towards more frequent use of IFX in primary level hospitals, possibly influenced by less availability of testing for CyA levels in these hospitals, but also the fact that these specialists believed that IFX may be more effective or faster-acting. However, there are no statistically significant differences in these responses (p=0.26). A general analysis of the results of this survey shows that management of cases of ASUC is homogeneous regardless of the type of hospital, highlighting that there are treatment criteria which are shared by the majority of specialists in our region.

ConclusionsBased on the results obtained in this survey, we can conclude that the management of ASUC in our environment adheres relatively well to the treatment recommendations established by the current consensus guidelines. The rescue treatment most commonly used in cases refractory to corticosteroid therapy is IFX, and the modified regimens for this biological drug (accelerated or intensified) are used with increasing frequency. However, more evidence is required to support their use.

Conflict of interestIR-L: funding to attend conferences, participation in training activities or scientific consultancy: MSD, Pfizer, Abbvie, Takeda, Janssen, Tillotts Pharma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Ferring, Dr. Falk Pharma and Otsuka Pharmaceutical.

RF-I: funding to attend conferences, participation in training activities or scientific consultancy: MSD, Abbvie, Takeda, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Casen Fleet.

PN: scientific consultancy, research support and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals and Otsuka Pharmaceutical. No participation in consultancies during time of presidency of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis].

JPG: scientific consultancy, research support and/or training activities: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

This study has been possible thanks to the participation of members of GETECCU.

We are also grateful for Urko Aguirre's (Research Unit, Hospital de Galdakao) contributions to the statistical analysis.

Please cite this article as: Rodríguez-Lago I, Ferreiro-Iglesias R, Nos P, Gisbert JP, en representación del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU). Manejo de la colitis ulcerosa aguda grave en España: Resultados de una encuesta sobre práctica clínica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:90–101.