It is widely acknowledged that inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with a high prevalence of sexual dysfunction (SD). However, there is a notable paucity of specific literature in this field. This lack of information impacts various aspects, including the understanding and comprehensive care of SD in the context of IBD. Furthermore, patients themselves express a lack of necessary attention in this area within the treatment of their disease, thus creating an unmet need in terms of their well-being.

The aim of this position statement by the Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) is to provide a review on the most relevant aspects and potential areas of improvement in the detection, assessment, and management of SD in patients with IBD and to integrate the approach to sexual health into our clinical practice. Recommendations are established based on available scientific evidence and expert opinion. The development of these recommendations by GETECCU has been carried out through a collaborative multidisciplinary approach involving gastroenterologists, gynecologists, urologists, surgeons, nurses, psychologists, sexologists, and, of course, patients with IBD.

Es ampliamente reconocido que la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) se asocia con una alta prevalencia de disfunción sexual (DS). Sin embargo, existe una notable escasez de publicaciones específicas en este ámbito. Esta falta de información repercute en diferentes aspectos, incluyendo la comprensión y atención integral de la DS en el contexto de la EII. Además, los propios pacientes expresan esta limitación dentro del tratamiento de su enfermedad, generando así una necesidad insatisfecha en términos de su bienestar.

El objetivo del presente documento de posicionamiento del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) es realizar una revisión sobre los aspectos más relevantes y las posibles áreas de mejora en la detección, evaluación y manejo de la DS en personas con EII para integrar el abordaje de la salud sexual en nuestra práctica clínica. Se establecen recomendaciones basadas en la evidencia científica disponible y la opinión de expertos. La elaboración de estas recomendaciones de GETECCU se ha efectuado a través de un enfoque colaborativo multidisciplinar en el que participan especialistas en gastroenterología, ginecología, urología, cirugía, enfermería, psicología, sexología y, por supuesto, pacientes con EII.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), mainly Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), is a chronic and progressive condition which has a significant impact on the quality of life of people who suffer from it. In recent decades, significant progress has been achieved in the treatment of IBD, thanks to a better understanding of its pathophysiological bases and the development of new drug therapies. These advances have not only enabled treatment of the associated symptoms, but also for better control to be achieved, made evident by the return to normal of biomarkers and the improvement of endoscopic lesions. Beyond these improvements, more ambitious and relevant objectives for patients are pursued in the approach to IBD, such as improving their quality of life and preventing disability.1 By adopting an approach based on the biopsychosocial model, it is recognised that not only biological, but also psychological and social aspects influence the well-being of an individual. Important in this context is the fundamental role that sexuality plays in quality of life as perceived by patients.

Throughout the 20th century, the greatest innovations occurred in the scientific study of human sexuality, especially in areas such as medicine and psychology, where more systematic theories and methods were developed to understand it. This progress has led to it being considered not only as a fundamental factor for people’s well-being and quality of life, but also as an essential element in health promotion.2 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines sexuality as a central element of the human being which includes aspects such as sexual identity and orientation, pleasure, eroticism and reproduction. It is expressed through thoughts, behaviours and relationships, and is influenced by various factors, such as physical, emotional, cognitive and sociocultural components.3 Sexual health is defined as a state of physical, emotional, mental and social well-being related to sexuality.3

Patients with IBD have a variety of disease-related characteristics that could impact sexual health. These include the incidence and prevalence of the diagnosis during a crucial period for social and sexual relationships, its chronic and intermittent nature, as well as clinical manifestations such as abdominal pain, faecal incontinence, rectal bleeding and/or perianal disease, which also interfere with personal intimacy. The potential repercussions of the condition, such as surgical interventions, malnutrition, fatigue, affective disorders and altered body image, in the case of stomas for example, can also have an impact on the sexual health of these subjects.4–6

For an integrated approach, we need to be aware of and able to detect and treat all aspects that might affect quality of life in people with chronic diseases, and sexual health should obviously be one of them.7 However, sexuality is still a taboo subject and there are significant barriers to communication in different situations, such as discussing sex with a partner, socially or with a healthcare worker. A survey of gastroenterologists from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) showed that many do not address sexual function in patients with IBD due to lack of knowledge (33%) or discomfort (20%), and only 14% discuss it regularly in their clinics.8 Subjects, however, consider their sexuality to be a priority in the treatment of their disease and perceive that this aspect is not always adequately treated during their appointments.9–12

Recognising the absence of specific guidelines to help us assess sexual dysfunction (SD) in patients with IBD in gastroenterology clinics, this position statement is aligned with the previous efforts of the Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) [Spanish Working Group on Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis], where guidelines have been outlined in aspects of this disease.13–27 Our goal is to lay the foundations for more structured clinical practice which recognises and addresses sexual health in people with IBD.

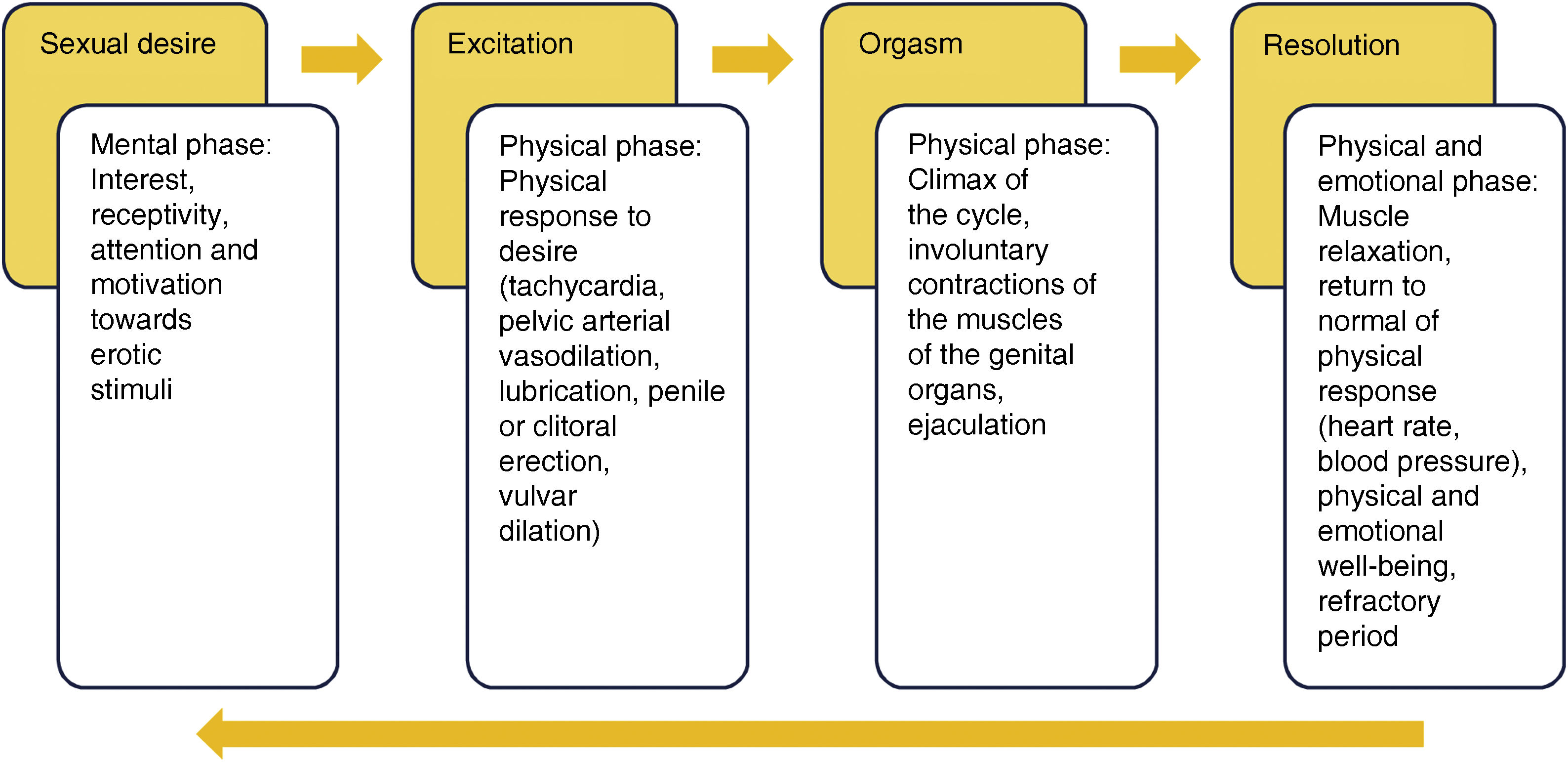

ConceptsHow is sexual dysfunction defined? Are the concepts clear?The sexual response involves a series of phases, beginning with sexual desire and ending with resolution. Each phase involves a mixture of cognitive and emotional elements which interact with each other and with the next phases (Fig. 1). SD refers to the presence of persistent or recurrent difficulties in one or more phases of the sexual response cycle, generating a negative impact on a person’s satisfaction and general well-being.

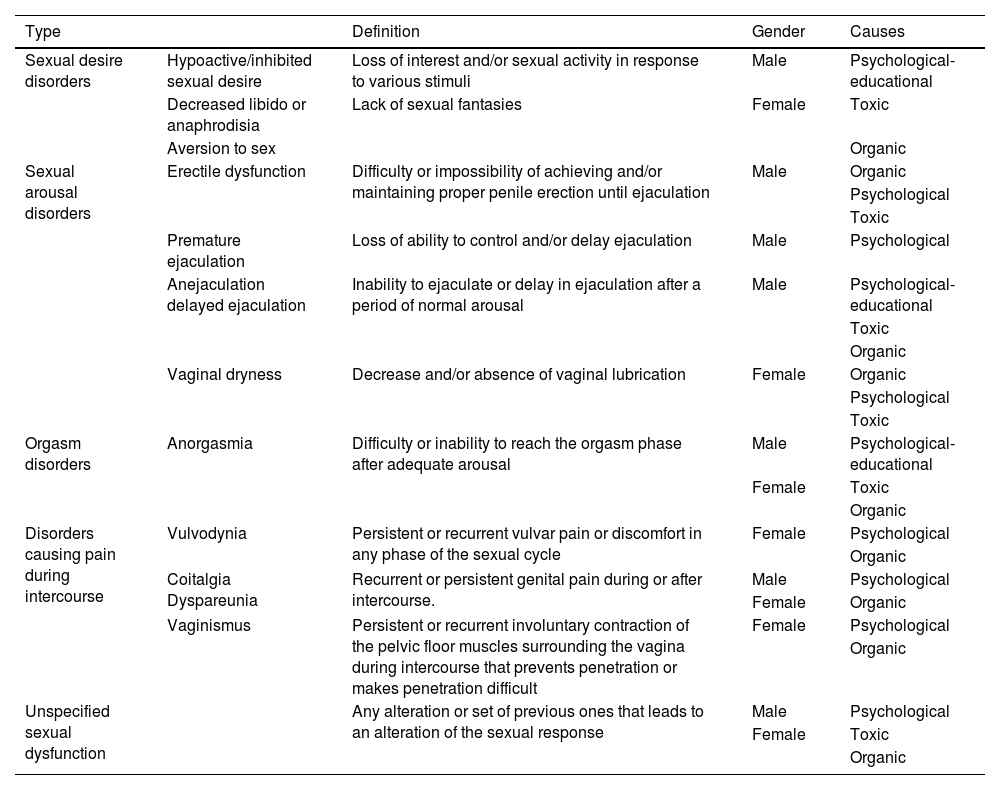

SD is a broad term and it can manifest itself in different forms, such as problems with sexual desire, arousal, orgasm, pain during intercourse and satisfaction, which can be associated with physical, emotional, interpersonal and/or social causes. The definitions and causes are shown in Table 1.

Recommendation. It is essential that in the investigation of and approach to SD in IBD, clear definitions are used and the many different ways in which it can manifest are taken into account, considering physical and emotional, interpersonal and social causes. This will allow for accurate assessment and appropriate treatment of affected patients.

Definitions and causes of SD.

| Type | Definition | Gender | Causes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual desire disorders | Hypoactive/inhibited sexual desire | Loss of interest and/or sexual activity in response to various stimuli | Male | Psychological-educational |

| Decreased libido or anaphrodisia | Lack of sexual fantasies | Female | Toxic | |

| Aversion to sex | Organic | |||

| Sexual arousal disorders | Erectile dysfunction | Difficulty or impossibility of achieving and/or maintaining proper penile erection until ejaculation | Male | Organic |

| Psychological | ||||

| Toxic | ||||

| Premature ejaculation | Loss of ability to control and/or delay ejaculation | Male | Psychological | |

| Anejaculation delayed ejaculation | Inability to ejaculate or delay in ejaculation after a period of normal arousal | Male | Psychological-educational | |

| Toxic | ||||

| Organic | ||||

| Vaginal dryness | Decrease and/or absence of vaginal lubrication | Female | Organic | |

| Psychological | ||||

| Toxic | ||||

| Orgasm disorders | Anorgasmia | Difficulty or inability to reach the orgasm phase after adequate arousal | Male | Psychological-educational |

| Female | Toxic | |||

| Organic | ||||

| Disorders causing pain during intercourse | Vulvodynia | Persistent or recurrent vulvar pain or discomfort in any phase of the sexual cycle | Female | Psychological |

| Organic | ||||

| Coitalgia Dyspareunia | Recurrent or persistent genital pain during or after intercourse. | Male | Psychological | |

| Female | Organic | |||

| Vaginismus | Persistent or recurrent involuntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles surrounding the vagina during intercourse that prevents penetration or makes penetration difficult | Female | Psychological | |

| Organic | ||||

| Unspecified sexual dysfunction | Any alteration or set of previous ones that leads to an alteration of the sexual response | Male | Psychological | |

| Female | Toxic | |||

| Organic |

SD: sexual dysfunction.

When evaluating the prevalence of SD in patients with IBD, we encounter the limitation that the assessment parameters are different for males and females. In males, they are more homogeneous, generally focused on erectile dysfunction, while in women, the assessment criteria are less defined, resulting in wide variability between studies.28,29 Despite this, the prevalence of SD in subjects with IBD is reported to be notably higher in females, with rates ranging from 49% to 97%,11,30–32 far exceeding the figures for the general population (19%–28%) and other chronic diseases, such as rheumatological conditions (31%–75%)33,34 or psoriasis (23%–71%).35 The prevalence of SD in males is between 14% and 39%,11,31,36 exceeding the 7% in the general population. Females usually report decreased sexual desire and difficulty reaching orgasm,11 while males more frequently report erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction and reduced libido.11,37 This difference in prevalence and manifestations of SD between genders in people with IBD reflects a similar trend observed in other chronic conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis.38

The studies do not offer definitive conclusions regarding the variations in the prevalence of SD between CD and UC.39–42 However, it is suggested that patients with CD, especially with perianal involvement, could be more likely to experience dyspareunia.39,40

What is the psychological impact of sexual dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease?SD in patients with IBD can interfere with a satisfactory sex life, affecting self-image, self-esteem and the relationship. It can also intensify anxiety during intimacy and, if persistent, can trigger emotional disorders and stress. This dynamic can generate a cycle of mutual influences where emotional distress aggravates SD. According to research, 45% of subjects report that IBD has interrupted their sexual activity, and for 30%, this disease has even contributed to the end of their relationships.40,42 In the young population, interference may be more pronounced, reducing sexual interest and satisfaction.32 Additionally, the lack of accurate information and myths about sexuality can lead to insecurities and feelings of guilt, which in turn can make communication and continuity of sexual relationships difficult.

Recommendation. Due to the impact of SD on the quality of life of IBD patients, it is imperative to develop robust educational strategies that provide accurate information on the interaction between IBD and sexual health. In addition, emphasis should be placed on dismantling myths about sexuality and offering psychological support to manage anxiety and other related emotional disorders.

The perception of lack of attention to sexual health felt by subjects with IBD is evident and is supported by multiple studies.8,10,43–45 Both patients and gastroenterologists acknowledge that sexual health is rarely discussed during consultations, as was demonstrated in a collaborative study carried out in our setting between GETECCU and the Asociación de Enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (ACCU) [Association of Crohn’s and Ulcerative Colitis Patients].44 Barriers to addressing SD include fear and embarrassment in starting these conversations, lack of training for professionals, and time limitations.8,10 Despite the existence of SD assessment scales, the lack of specific IBD tools validated in the Spanish population9,12 and the lack of consensus on which scales to use, together with their irregular application in clinical practice, continue to be a challenge.43,46,47 Additionally, there is a need to expand demographic representation in studies on SD in IBD. Most studies have mainly included females and people aged 30–40, introducing a gender and age bias. The causes of and clinical approach to SD vary between males and females (Tables 2 and 3), but should also be sensitive to age. A recent study challenged the stereotype of sexual inactivity in older people, showing their interest in discussing sexual expression and activity during consultations.10 In addition, the scarcity of data on sexual orientation and gender identity leaves subjects belonging to the group of lesbians, gays, bisexuals, transgender, queer, intersex, asexual or other sexual or gender diverse minorities (LGBTQIA+) in a little-explored terrain, on top of the fact that this group already tends to experience greater deterioration in health and well-being.48 The limited research available reveals specific needs and concerns in these groups, including concerns about how gender-affirming treatments might affect IBD.49–51

Recommendation. It is recommended to improve the training of healthcare professionals on SD in IBD and promote an open and non-prejudiced dialogue on sexual health in consultations. It is crucial to expand demographic diversity in future research to better understand how SD affects different groups of IBD patients. Research on the intersection of sexual orientation, gender identity, and IBD should also be encouraged to provide inclusive and targeted care that addresses the needs of the LGBTQIA+ community and other under-represented groups in studies.

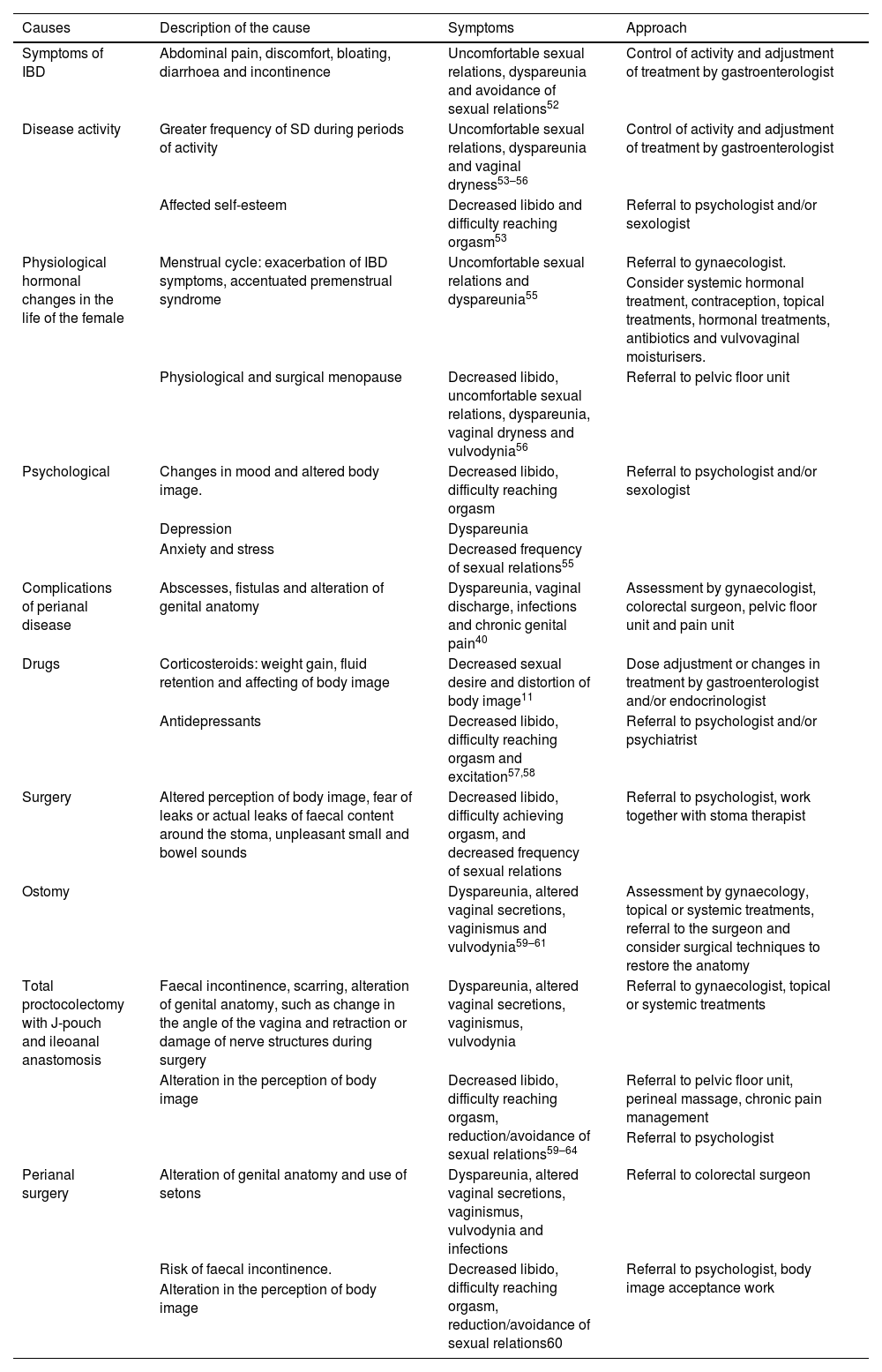

Causes and approach to SD in females with IBD.

| Causes | Description of the cause | Symptoms | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms of IBD | Abdominal pain, discomfort, bloating, diarrhoea and incontinence | Uncomfortable sexual relations, dyspareunia and avoidance of sexual relations52 | Control of activity and adjustment of treatment by gastroenterologist |

| Disease activity | Greater frequency of SD during periods of activity | Uncomfortable sexual relations, dyspareunia and vaginal dryness53–56 | Control of activity and adjustment of treatment by gastroenterologist |

| Affected self-esteem | Decreased libido and difficulty reaching orgasm53 | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist | |

| Physiological hormonal changes in the life of the female | Menstrual cycle: exacerbation of IBD symptoms, accentuated premenstrual syndrome | Uncomfortable sexual relations and dyspareunia55 | Referral to gynaecologist. |

| Consider systemic hormonal treatment, contraception, topical treatments, hormonal treatments, antibiotics and vulvovaginal moisturisers. | |||

| Physiological and surgical menopause | Decreased libido, uncomfortable sexual relations, dyspareunia, vaginal dryness and vulvodynia56 | Referral to pelvic floor unit | |

| Psychological | Changes in mood and altered body image. | Decreased libido, difficulty reaching orgasm | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist |

| Depression | Dyspareunia | ||

| Anxiety and stress | Decreased frequency of sexual relations55 | ||

| Complications of perianal disease | Abscesses, fistulas and alteration of genital anatomy | Dyspareunia, vaginal discharge, infections and chronic genital pain40 | Assessment by gynaecologist, colorectal surgeon, pelvic floor unit and pain unit |

| Drugs | Corticosteroids: weight gain, fluid retention and affecting of body image | Decreased sexual desire and distortion of body image11 | Dose adjustment or changes in treatment by gastroenterologist and/or endocrinologist |

| Antidepressants | Decreased libido, difficulty reaching orgasm and excitation57,58 | Referral to psychologist and/or psychiatrist | |

| Surgery | Altered perception of body image, fear of leaks or actual leaks of faecal content around the stoma, unpleasant small and bowel sounds | Decreased libido, difficulty achieving orgasm, and decreased frequency of sexual relations | Referral to psychologist, work together with stoma therapist |

| Ostomy | Dyspareunia, altered vaginal secretions, vaginismus and vulvodynia59–61 | Assessment by gynaecology, topical or systemic treatments, referral to the surgeon and consider surgical techniques to restore the anatomy | |

| Total proctocolectomy with J-pouch and ileoanal anastomosis | Faecal incontinence, scarring, alteration of genital anatomy, such as change in the angle of the vagina and retraction or damage of nerve structures during surgery | Dyspareunia, altered vaginal secretions, vaginismus, vulvodynia | Referral to gynaecologist, topical or systemic treatments |

| Alteration in the perception of body image | Decreased libido, difficulty reaching orgasm, reduction/avoidance of sexual relations59–64 | Referral to pelvic floor unit, perineal massage, chronic pain management | |

| Referral to psychologist | |||

| Perianal surgery | Alteration of genital anatomy and use of setons | Dyspareunia, altered vaginal secretions, vaginismus, vulvodynia and infections | Referral to colorectal surgeon |

| Risk of faecal incontinence. | Decreased libido, difficulty reaching orgasm, reduction/avoidance of sexual relations60 | Referral to psychologist, body image acceptance work | |

| Alteration in the perception of body image |

SD: sexual dysfunction; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

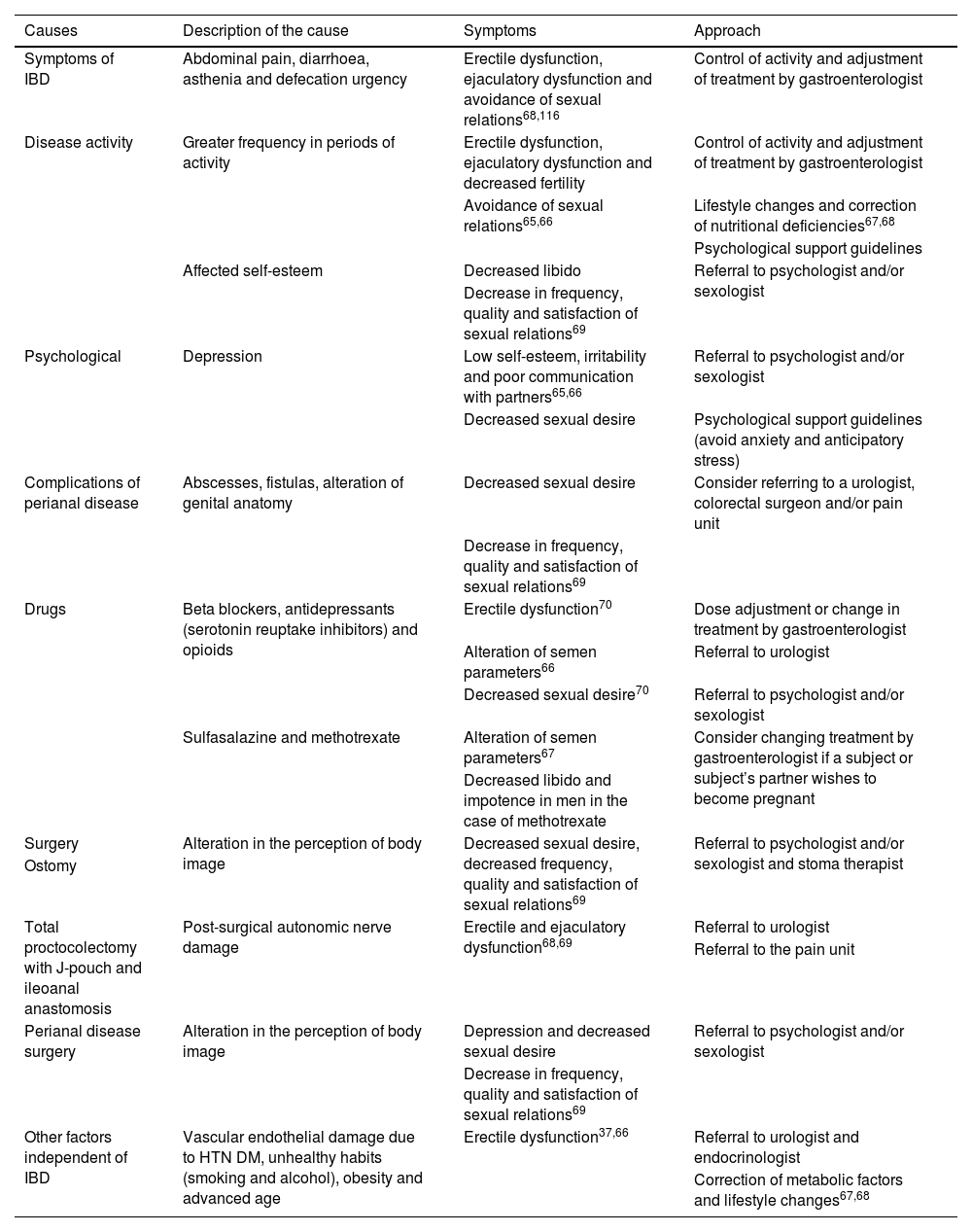

Causes and approach to SD in males with IBD.

| Causes | Description of the cause | Symptoms | Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms of IBD | Abdominal pain, diarrhoea, asthenia and defecation urgency | Erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction and avoidance of sexual relations68,116 | Control of activity and adjustment of treatment by gastroenterologist |

| Disease activity | Greater frequency in periods of activity | Erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction and decreased fertility | Control of activity and adjustment of treatment by gastroenterologist |

| Avoidance of sexual relations65,66 | Lifestyle changes and correction of nutritional deficiencies67,68 | ||

| Psychological support guidelines | |||

| Affected self-esteem | Decreased libido | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist | |

| Decrease in frequency, quality and satisfaction of sexual relations69 | |||

| Psychological | Depression | Low self-esteem, irritability and poor communication with partners65,66 | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist |

| Decreased sexual desire | Psychological support guidelines (avoid anxiety and anticipatory stress) | ||

| Complications of perianal disease | Abscesses, fistulas, alteration of genital anatomy | Decreased sexual desire | Consider referring to a urologist, colorectal surgeon and/or pain unit |

| Decrease in frequency, quality and satisfaction of sexual relations69 | |||

| Drugs | Beta blockers, antidepressants (serotonin reuptake inhibitors) and opioids | Erectile dysfunction70 | Dose adjustment or change in treatment by gastroenterologist |

| Alteration of semen parameters66 | Referral to urologist | ||

| Decreased sexual desire70 | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist | ||

| Sulfasalazine and methotrexate | Alteration of semen parameters67 | Consider changing treatment by gastroenterologist if a subject or subject’s partner wishes to become pregnant | |

| Decreased libido and impotence in men in the case of methotrexate | |||

| Surgery | Alteration in the perception of body image | Decreased sexual desire, decreased frequency, quality and satisfaction of sexual relations69 | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist and stoma therapist |

| Ostomy | |||

| Total proctocolectomy with J-pouch and ileoanal anastomosis | Post-surgical autonomic nerve damage | Erectile and ejaculatory dysfunction68,69 | Referral to urologist |

| Referral to the pain unit | |||

| Perianal disease surgery | Alteration in the perception of body image | Depression and decreased sexual desire | Referral to psychologist and/or sexologist |

| Decrease in frequency, quality and satisfaction of sexual relations69 | |||

| Other factors independent of IBD | Vascular endothelial damage due to HTN DM, unhealthy habits (smoking and alcohol), obesity and advanced age | Erectile dysfunction37,66 | Referral to urologist and endocrinologist |

| Correction of metabolic factors and lifestyle changes67,68 |

DM: diabetes mellitus; SD: sexual dysfunction; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; HTN: hypertension.

SD in females can be triggered by a variety of factors, such as age, psychological conditions (mainly depression, anxiety and stress), conflicts in relationships, fatigue, lack of privacy, history of sexual abuse, adverse effects of treatments, and chronic diseases such as endometriosis, which can lead to unsatisfactory, uncomfortable or painful sexual experiences.71–73 In the case of females with IBD, it has been recognised for more than three decades that a significant portion of patients experience sexual challenges, although these difficulties are often underdiagnosed.74,75 Recent research has shown that, compared to males, females experience and cope with IBD differently. Hormonal variations throughout life (menarche, menstrual cycle, pregnancy, menopause, surgical menopause) affect both sexual health and the manifestation of IBD, triggering or exacerbating SD.57

In relation to the causes of SD in females with IBD, a correlation has been identified with the disease’s gastrointestinal symptoms, its complications, and the medical and surgical treatments required (Table 2).

Recommendation. It is important to take into consideration the complexity and interrelation of the factors that contribute to SD in females with IBD, as they can serve as a guide to understanding how different aspects of the disease and its treatment can impact their sexual health, and so make it easier to develop more personalised and comprehensive management strategies.

IBD can have a significant impact on male sexual health and appears to be determined by the interaction of multiple different elements. A number of factors directly related to IBD have been described, such as drug treatments, surgery, psychological factors and disease activity37,65 and others independent of IBD, such as diabetes or hypertension (HTN), which contribute to the development and perpetuation of male SD, and must be taken into account to establish an appropriate comprehensive treatment66 (Table 3).

Various studies have linked certain non-specific drugs for IBD, such as beta-blockers,76 antidepressants (predominantly serotonin reuptake inhibitors)70,77 and opioids,78,79 with the development of SD in males and possible changes in the seminal parameters that could reduce their fertility.66 In relation to specific medications for IBD, it has been pointed out that both sulfasalazine and methotrexate could be associated with male infertility problems due to alterations in semen quality. Furthermore, it has been described that ciclosporin and infliximab could affect the motility and morphology of sperm. However, the evidence in this regard is limited and future studies are required to evaluate this relationship.67 Large-scale controlled studies have corroborated that filgotinib does not cause changes in semen characteristics or sex hormones in patients with IBD.80,81 Aside from the semen alterations mentioned, to date, no clear relationship has been determined between specific drug treatments for IBD and the development of SD.

Recommendation. To address SD in males with IBD, it is essential to consider physical and psychological factors, including the influence of drug treatments and disease activity. In addition, it is important to assess and control cardiovascular risk factors and offer psychological support, as well as treatment adjustment by gastroenterologists, as necessary.

There is evidence that the gastrointestinal symptoms of IBD, such as diarrhoea and abdominal pain, along with other extra-intestinal symptoms, such as asthenia, can negatively affect a patient’s sexuality.52,82,83 In fact, the association between disease activity and SD in subjects with IBD has been described in numerous studies47,52,53,82,83 and up to 34% perceive that it has a direct impact on their sexual health.47 This relationship is independent of the type of IBD, since both individuals with UC and those with active CD have higher rates of SD than people in remission (31.4% vs 8.8% and 42.4% vs 13.6% respectively).84 However, there is still debate about whether disease activity affects SD as, in other studies, the influence does not seem to be so consistent,85 especially when comparing patients with IBD to healthy controls.31,86

The analysis of the relationship between intestinal inflammation and SD in patients with IBD has not revealed significant differences in the prevalence of SD in subjects with or without endoscopic activity (54.2% vs 62.9%; p = 0.42), or in those with high faecal calprotectin levels (≥200 µg/g) (48.4% vs 59.1%; p = 0.58).87 However, a significantly higher prevalence of SD has been found in females with clinical activity (70% vs 42%; p < 0.05). Therefore, it appears that symptoms related to disease activity, rather than the activity itself, could be associated with SD in patients during periods of flare-up. These findings are consistent with surveys in females with IBD, in which decreased sexual desire has been identified (odds ratio [OR] = 1.8; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.0–3.2) and a reduction in the frequency of sexual relations linked to the severity of the disease (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.4–4.7).53

Recommendation. Despite controversy over whether IBD activity per se influences SD, an association is observed between symptoms related to disease activity and SD. Special attention should be paid to females with IBD during the clinically active phases, as they may experience decreased sexual desire and a reduction in the frequency of sexual relations linked to the severity of the disease.

Immunomodulatory and biologic drugs, frequently used in the treatment of IBD, could have a negative impact on sexual health. However, current scientific evidence on their influence is limited and does not establish a solid relationship with SD in patients with IBD.67,88 A relevant aspect to consider is the possible impact that therapies to control IBD may have on the perception of body image. Along these lines, the cosmetic effects associated with corticosteroids, such as truncal obesity, acne or hirsutism, contribute to a negative perception that can limit their sex life in 21% of females and 4% of males with IBD.11 This correlation between corticosteroids, the altered perception of body image, and the consequent decrease in sexual satisfaction and quality of life is supported by other research, although it is not observed with immunomodulators or biologic drugs.89

It is relevant to consider that patients receiving immunomodulatory, biological and corticosteroid therapies may have greater inflammatory activity or more aggressive disease patterns. It is therefore necessary to have more evidence that controls for these possible confounding factors to discern whether the treatment determines SD or whether the disease activity itself is the cause. An additional challenge in measuring the impact of IBD therapies on sexual function is that most studies have adopted a survey format, making it difficult to establish a causal association from a methodological point of view. However, a survey of IBD doctors through the AGA revealed that 62% believed the drugs used to control the disease could have a negative effect on patients’ sexual health.8

Recommendation. Although the evidence on the impact of drugs used in IBD on SD is limited, attention should be paid to the cosmetic effects of corticosteroids on the perception of body image, which can negatively affect sex life, especially in females. Further studies are required to better understand the relationship between IBD treatment and SD, considering disease activity and other confounding factors.

Remission of inflammatory activity in IBD, even through surgery, is generally accompanied by improved physical and sexual health in patients. In this context, it has been shown that intestinal resections in subjects with CD improve their quality of life.60,90 However, certain surgical approaches necessary in some individuals with IBD, which involve aggression in the pelvic area, can affect sexual function by causing alterations in the innervation of the genitals or distortion of the anatomy of the pelvis.45,91 Specifically, after pelvic surgery, there is a risk of SD in males, such as erectile dysfunction, and in females, such as dyspareunia, decreased vaginal lubrication or loss of proprioception.92,93

Although evidence suggests that total proctocolectomy with J-pouch and ileoanal anastomosis may have a beneficial effect on sexual function in both male and female patients,92,94 it is important to consider that the creation of the pouch may have an impact, probably due to a combination of nerve damage during rectal dissection and anatomical changes deriving from pelvic dissection, such as adhesions or changes in the angulation of the vagina in females. Furthermore, the proximity of the pouch to the vagina and the healing process can cause dyspareunia, which can increase in up to 25% of patients who have surgery. However, overall no change or decrease in general sexual satisfaction has been found, and sexual function even seems to improve in females approximately 12 months after surgery.92,95,96 There are also specific challenges associated with the pouch, such as faecal incontinence or increased frequency of bowel movements, which can affect various aspects, such as desire, arousal and sexual satisfaction.59 Total proctocolectomy with abdominoperineal inter-sphincter amputation has also been shown to have an unfavourable effect on sexual function in males and females, although the aggravating factor is probably the presence of an end ileostomy. Patients undergoing this procedure may experience concerns related to pouch leaks, odours or distortion of body image, which contribute to impaired sexual function.43,94,97–99

The evidence regarding sexual function in patients undergoing surgery for perianal fistulising CD is limited. Although a negative impact of this intervention is suggested, the available data only indicate a non-significant trend toward deterioration of sexual function in females.60 It should be noted that subjects who undergo these procedures have a high risk of experiencing faecal incontinence, which translates into a general deterioration in quality of life and, possibly also, in sexual function in males.60

It is important to keep in mind that patients demand a better approach to the impact that surgery could have on their sexual health. In a survey of 632 people (80% female, 65% with IBD) with intestinal/anal surgery (85% with stomas) indicated a negative effect on their sexual activity after surgery, and a lack of information and support beforehand from healthcare professionals.100

Psychological aspectsIn relation to the emotional distress that patients with IBD may experience, studies indicate that psychological factors play a fundamental role in causing, aggravating and maintaining SD, especially depression and stress.101 Depression in particular is one of the main disorders that affects desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, pain and sexual satisfaction.31,52,53,102 It is important to remember that the rate of emotional disorders in people with IBD is higher than in other chronic diseases and the general population.103,104 In addition, low self-esteem, fear of rejection, flare-ups of disease activity, fatigue, defecatory urgency, uncertainty and embarrassment about possible leaks or incontinence during the sex act can significantly interfere, leading many patients to avoid sexual relationships.

What is the current status of management strategies for sexual dysfunction in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and what methods or approaches could optimise management?GastroenterologyThe approach to SD in patients with IBD by gastroenterologists has evolved, now focusing not only on the control of inflammation, but also on improving their quality of life, this being demonstrated by the inclusion of quality-of-life indices in different studies.105,106

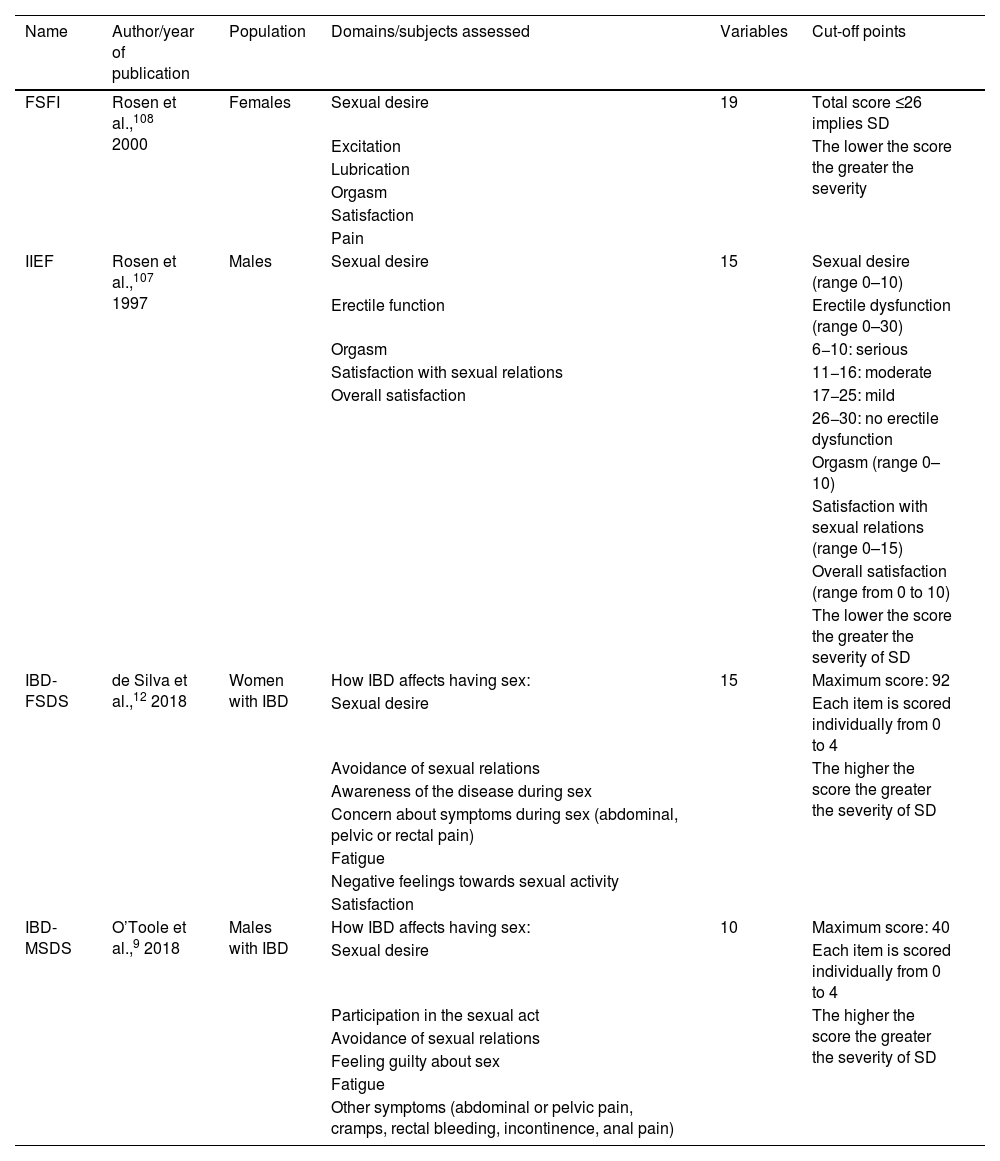

The indices used to evaluate SD in IBD, such as the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) and the International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)107,108 (Table 4), do not consider specific symptoms of IBD, such as diarrhoea or perianal complications, although they have been validated in the Spanish population (Tables 1 and 2 of the Supplementary material).109,110 However, two specific scales have been developed for IBD, Female Sexual Dysfunction Scale (IBD-FSDS) and IBD-specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale (IBD-MSDS) (Tables 3 and 4 of the Supplementary material), which demonstrate high internal validity and correlation with other indices of female and male SD used in the general population.111 However, these have not been validated in the Spanish population, which limits their clinical use.

SD assessment indices and scales.

| Name | Author/year of publication | Population | Domains/subjects assessed | Variables | Cut-off points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FSFI | Rosen et al.,108 2000 | Females | Sexual desire | 19 | Total score ≤26 implies SD |

| Excitation | The lower the score the greater the severity | ||||

| Lubrication | |||||

| Orgasm | |||||

| Satisfaction | |||||

| Pain | |||||

| IIEF | Rosen et al.,107 1997 | Males | Sexual desire | 15 | Sexual desire (range 0–10) |

| Erectile function | Erectile dysfunction (range 0–30) | ||||

| Orgasm | 6−10: serious | ||||

| Satisfaction with sexual relations | 11−16: moderate | ||||

| Overall satisfaction | 17−25: mild | ||||

| 26−30: no erectile dysfunction | |||||

| Orgasm (range 0–10) | |||||

| Satisfaction with sexual relations (range 0–15) | |||||

| Overall satisfaction (range from 0 to 10) | |||||

| The lower the score the greater the severity of SD | |||||

| IBD-FSDS | de Silva et al.,12 2018 | Women with IBD | How IBD affects having sex: | 15 | Maximum score: 92 |

| Sexual desire | Each item is scored individually from 0 to 4 | ||||

| Avoidance of sexual relations | The higher the score the greater the severity of SD | ||||

| Awareness of the disease during sex | |||||

| Concern about symptoms during sex (abdominal, pelvic or rectal pain) | |||||

| Fatigue | |||||

| Negative feelings towards sexual activity | |||||

| Satisfaction | |||||

| IBD-MSDS | O’Toole et al.,9 2018 | Males with IBD | How IBD affects having sex: | 10 | Maximum score: 40 |

| Sexual desire | Each item is scored individually from 0 to 4 | ||||

| Participation in the sexual act | The higher the score the greater the severity of SD | ||||

| Avoidance of sexual relations | |||||

| Feeling guilty about sex | |||||

| Fatigue | |||||

| Other symptoms (abdominal or pelvic pain, cramps, rectal bleeding, incontinence, anal pain) |

SD: sexual dysfunction; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; FSFI: female sexual function index; IBD-FSDS: IBD-specific Female Sexual Dysfunction Scale; IBD-MSDS: IBD-specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale; IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function.

For adequate management of SD in patients with IBD, it is advisable to take a thorough medical history, encourage open dialogues about sexuality and perform a physical examination and psychological assessment, in addition to applying specific SD indices.109,110 This should be done in conjunction with a holistic approach after the diagnosis of SD.

NursingThe role of nurses is essential to provide adequate information, as they can establish a close relationship in a favourable environment, such as a specialised clinic.112 In fact, in a study in which patients were surveyed about different aspects of their sexual function linked to the disease, they considered the IBD nurse to be the most appropriate healthcare professional setting to provide advice.100 The nurse therefore plays a vital role in the detection and management of SD in subjects with IBD, their work being recognised by the European nursing group on CD and UC (Nurses-European Crohn’s & Colitis Organisation; N-ECCO).113 The IBD nurse should be trained to identify sexual problems, provide appropriate information and support, and collaborate with other specialists for an integrated and personalised approach. Problems should be detected through normalising sexuality and asking direct questions adapted to the patient’s wishes.112 The information provided should be inclusive, covering different sexual practices, and nursing staff must be trained to avoid prejudice or biased points of view.

In this context, the PLISSIT model (permission, limited information, specific suggestions and intensive therapy), which systematises the interview in stages, could be useful. It consists of obtaining permission (P) from the patient, providing limited information (LI), giving specific suggestions (SS), and, if necessary, offering intensive therapy (IT), which includes education, changes in habits and referral to specialists if necessary.114

Recommendation. Promoting the training of nursing staff in addressing SD in patients with IBD is recommended, cultivating an integrated and personalised approach. Implementation of the PLISSIT model could better structure the interview and follow-up. Furthermore, it is vital to promote education and information on sexuality adapted to different sexual practices, helping to normalise the conversation about SD.

Gynaecological assessment in patients with IBD is crucial to identify and treat modifiable causes of SD, through specific interventions, such as topical moisturisers, hormonal treatments, lubricants, probiotics, antiseptics, antibiotics, perineal massage, dilators, pelvic floor exercises, and systemic therapies, such as contraception for suppressing menstruation or hormone replacement therapy in menopausal women. Referral to units specialised in pelvic floor and to colorectal surgeons is also relevant to assess and treat fistulas and restore perineal anatomy, if applicable, which can improve sexual function. Psychological assessment, individualised therapy and sexual counselling are vital to address the psychosocial aspects of patients and their partners (Table 2).

It is important to rule out SD in people with clinically active IBD and consider that the exacerbation of symptoms may be related to changes in the menstrual cycle, informing patients to help them understand that the worsening is temporary.73,74

Gynaecologists play a crucial role in the diagnosis and treatment of SD, requiring a comprehensive assessment of patients' sexual health and raising awareness of the specific causes of SD in people with IBD. The emphasis has to be on the need for a multidisciplinary approach to provide information and education on the relationship between IBD and sexual health, adapted to the age and sexual orientation of the female patients, enabling open communication about their sex life with the medical team. Additionally, as specialists in female sexual health, they have a key role in raising awareness, supporting research and generating educational projects to improve the early diagnosis and treatment of SD in patients with IBD.

UrologyThe urological approach to SD in patients with IBD requires a detailed medical history that includes drug treatment, cardiovascular risk factors and previous surgical procedures, accompanied by a rigorous sexual and physical assessment to identify deformities or painful areas in the genital or perineal region.115 It is important to measure testosterone levels given their influence on erectile and ejaculatory function. IBD can cause hypogonadism, affecting up to 40% of subjects, mainly due to chronic inflammation or the use of medications such as steroids and opioids.66,68

In terms of the urological treatment of SD, the first line of therapy for erectile dysfunction includes phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors, with additional alternatives such as topical or intraurethral alprostadil, penile vacuum devices, and intracavernosal injections with alprostadil if the initial interventions are not effective.69,115 Testosterone supplementation in cases of hypogonadism secondary to IBD is subject to debate. It is recommended only in cases with clinical repercussions due to erectile dysfunction, decreased libido and/or asthenia, and it is essential to consider dose adjustment or changes in medication which may affect testosterone levels.

Specific or non-IBD drug treatments that affect erectile function should be reassessed, considering dose adjustments or medication changes. Lifestyle modifications and correction of nutritional deficiencies, especially zinc, may also be beneficial.67,116,68

SurgerySurgery on patients with IBD can pose a challenge in terms of maintaining sexual function, as important anatomical structures could be damaged. However, advances in surgical techniques mean this risk can now be reduced. It is important for the intervention to be meticulous to avoid damage to the autonomic nerves, adjusting the total excision of the mesorectum according to the specific anatomy of the patient.94 Technologies such as laparoscopy and robotic surgery have shown a beneficial effect, especially in males, in whom greater preservation of erectile function has been reported, as well as a possible positive impact on sexual function in females.117 In cases of perianal disease, conservative surgery and the prudent use of setons contribute to a lower risk of SD, essentially in females.10,45,118

A proactive discussion about how surgery could affect sexual function is crucial during the preoperative assessment, considering the age and sexual orientation of the patients.10,45,105,118,119 This means that surgeons need to be well informed and use advanced techniques, while ensuring that subjects are aware of the risks and can discuss them without reservation.105 Having access to information on sexual complication rates at each medical centre helps make informed referrals to multidisciplinary units with more experience in complex procedures. Lastly, patients who require a stoma or who are to undergo surgery with potential risk of needing one would benefit from an integrated approach that includes education, emotional support, acceptance and personal growth, to help promote an improvement in quality of life and sexual function.98,120

PsychologyFrom this perspective, SD in patients with IBD is addressed by working on psychological symptoms that directly affect sexuality. Improving self-esteem and reducing the stigma associated with post-surgical physical and aesthetic changes are essential aspects. Anxiety, characterised by hypervigilance, is a known factor that impairs SD, especially in patients with IBD. Therefore, reducing hypervigilance may be useful in terms of improving sexual response in this context. Stress and low mood are also factors that can interfere with a satisfactory sexual experience. Promoting active listening by the patient with regard to their own body and improving emotional management are strategies which can contribute to optimised sexual health. Additionally, cognitive-behavioural therapy has been found to be beneficial in reducing anxiety and certain gastrointestinal symptoms, although the results are limited in this specific setting.121–123

Creating a comfortable environment in the clinic, guaranteeing privacy and cultivating an atmosphere of active listening to the patient, along with the healthcare professional taking the initiative to facilitate conversations about sexuality, are aspects that can improve the subject's feeling of security and help them express their concerns. Psychoeducation is vital for helping to resolve people’s uncertainties in this process.124

Healthcare professionals have opportunities to improve the relationship with the patient and address concerns related to sexuality at clinic visits or during hospital admissions. It is key that subjects express their difficulties or needs in this area, and this will enable open communication which will help reduce the impact and facilitate appropriate referrals to specialists if serious problems are detected.26

Recommendation. We suggest the incorporation of specialised psychologists in IBD units to ensure an integrated approach to patients’ recurrent problems and prevent possible future difficulties, enabling more effective management of SD. This, combined with the promotion of open communication, psycho-education and the adoption of cognitive-behavioural and other therapies, will provide a holistic approach to help improve subjects’ sexual functioning.

Sexology is a fundamental tool in the support of patients with IBD to reconstruct a new interest in/fascination with and experience of sex, either individually or as a couple, once their health has stabilised. Healthcare personnel play an important role here in referring subjects to sexology care to improve this aspect and alleviate the taboo surrounding SD.

The sexology approach is through cognitive-behavioural techniques adapted to the patient and the state of their disease at the time of the consultation. It begins with an in-depth interview about sex education, limiting ideas, taboos, sexual experiences and expectations. The emphasis is on an integrative vision and adaptability to the needs and desires of the subject, avoiding ableism in the interventions. The proposal of a new paradigm in sexology seeks to consider the patient from a holistic point of view with regard to their sexuality, promoting friendly spaces and a multidisciplinary approach for comprehensive care and guidance for their SD.

It is vital to know the patient’s medical history to provide adequate care and guidance, in order to have an understanding of the multifactorial nature of the SD, which could have been present before the IBD diagnosis or have become intensified afterwards. It is also crucial to maintain a gender and diversity perspective, without assuming the subject's sexual orientation or preferences.

The interventions focus on promoting connection and rediscovery with pleasure, the construction of eroticism, non-genital practices and focusing on the erotic body map. Sex complements, erotic toys and practices can be suggested that promote intimacy as a couple or individually, helping alleviate negative anticipatory thinking (hypervigilance), which in turn facilitates greater relaxation and activation of the human sexual response.

Recommendation. We recommend encouraging the incorporation of the figure of the sexologist in the holistic management of patients with IBD, promoting referral to these specialists in the case of SD. It is also advisable to move towards a paradigm in sexology that contemplates an integrative vision of sexuality, maintaining a gender and diversity perspective, and promoting friendly health spaces and personalised interventions that address the patient’s particular characteristics and desires.

The management of SD in people with IBD requires an integration of clinical and social approaches, highlighting the importance of their own perspective. Within this framework, patient associations emerge as essential platforms for reciprocal support and awareness regarding the repercussions of SD in IBD. Through awareness campaigns, these associations can demystify taboos around sexuality and IBD and provide supported information on how SD can affect them. They can also facilitate the collection of accurate data that reflects the reality of subjects with IBD, integrating the perspectives of all the social care and healthcare professionals involved.

Lastly, to improve self-identification and communication about SD, patient associations can offer training workshops. This would allow subjects to identify SD and discuss it with confidence during healthcare consultations.

Recommendation. We recommend strengthening collaboration between social care and healthcare professionals and patient associations for effective management of SD in people with IBD. Association campaigns and workshops are crucial to demystify taboos and facilitate communication about SD. Promoting data collection and analysis to identify areas for improvement and develop evidence-based strategies is encouraged.

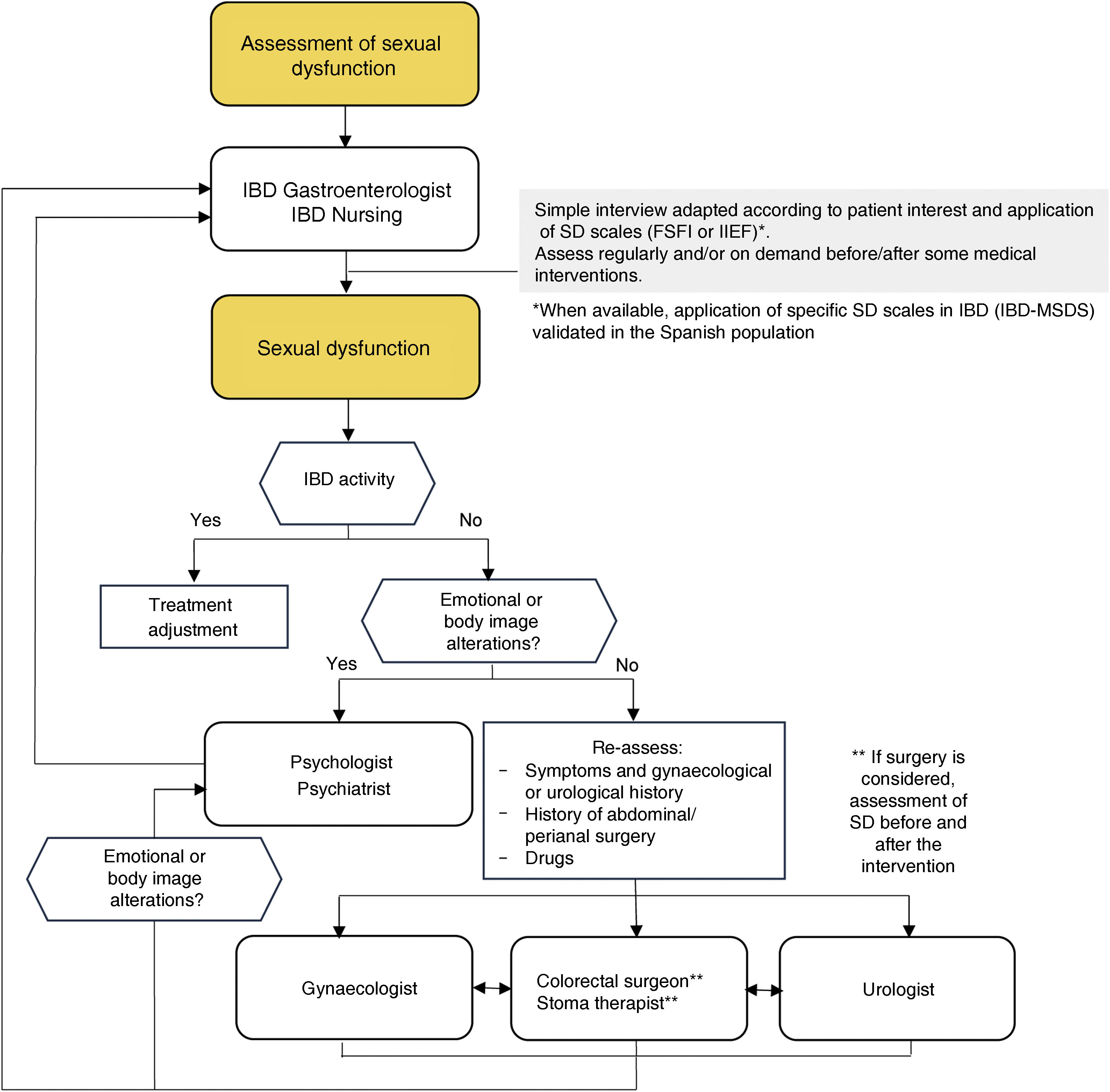

The purpose of this GETECCU positioning document is to integrate the approach to the sexual health of patients with IBD into our clinical practice. This is achieved through a collaborative and multidisciplinary approach that involves gastroenterologists, gynaecologists, urologists, surgeons, nursing staff, psychologists, sexologists and, of course, the IBD subjects themselves. We propose an algorithm for assessment, referral and collaboration between all the healthcare professionals involved, focused on the patients (Fig. 2).

SD management algorithm in patients with IBD.

SD: sexual dysfunction; IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; FSFI: female sexual function index108; IIEF: International Index of Erectile Function107; IBD-FSDS: IBD-specificFemale Sexual Dysfunction Scale12; IBD-MSDS: IBD-specific Male Sexual Dysfunction Scale.9

After carrying out an exhaustive review of the available scientific evidence and with the knowledge obtained from clinical practice, the experts participating in the consensus process have reached a unanimous agreement regarding the following statements for improving sexual satisfaction in patients with IBD:

- •

Recognise the importance of sexual health in patients with IBD and integrate the approach to this area into our clinical practice.

- •

Provide appropriate information and education on IBD-related SD, including its possible causes and treatment options.

- •

Promote open and taboo-free communication about sexuality with patients and their partners.

- •

Train different healthcare professionals so that they feel comfortable and qualified to address SD in people with IBD in collaboration with sexologists.

- •

Validate specific SD assessment scales in patients with IBD in the Spanish population.

- •

Develop specific guidelines and protocols to assess and treat SD in subjects with IBD in gastroenterology clinics.

- •

Conduct additional research on SD in specific groups of IBD patients such as the LGTBIQ + collective.

- •

Promote the incorporation of psychologists into multidisciplinary IBD units to address SD and other psychological comorbidities suffered by patients with IBD.

- •

Promote multidisciplinary collaboration between specialists in gastroenterology, gynaecology, urology, surgery, nursing, psychology and sexology to holistically address the sexual health of patients with IBD.

Marta Calvo Moya: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Lilly, Shire, Chiesi, Dr Falk Pharma, Faes Pharma, Ferring, Kern Pharma and Tillotts Pharma.

Francisco Mesonero: has received funding for educational activities, conferences and scientific advice/consulting from MSD, AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Kern Pharma, Dr. Falk Pharma, Celltrion Healthcare, Galapagos, Chiesi, Tillots Pharma and Faes Pharma.

Cristina Suárez: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from Ferring, Faes Pharma, AbbVie, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, Kern Pharma, and Tillotts Pharma.

Alejandro Hernández-Camba: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, Adacyte Therapeutics, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Kern Pharma, Faes Pharma, Takeda, Galapagos and Tillots Pharma.

Danízar Vásquez: has been a speaker or has received research funding from Gedeon Richter, Janssen, Ferring and Procare.

Fátima Benasach: has been a speaker or has received research funding from Exeltis, Italfarmaco and Faes Pharma.

Mariam Aguas: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, Faes Pharma, Ferring, Galapagos, Janssen, Kern Pharma, Pfizer, Takeda, and Tillotts Pharma.

Yago González-Lama: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Biogen, Amgen, Ferring, Faes Pharma, Chiesi, and Gebro Pharma.

Ana Echarri: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from Janssen, AbbVie, Pfizer, Galapagos, and MSD.

Pablo Bella: has been a speaker for or received research funding from Takeda, Janssen and Tillotts Pharma.

Noelia Cano: has been a speaker for or has received research funding from AbbVie, Takeda, Janssen, Lilly and Ferring.

María Isabel Vera: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from MSD, AbbVie, Pfizer, Ferring, Shire, Takeda, Tillots Pharma, Jannsen and Galapagos.

Yamile Zabana: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from AbbVie, Adacyte, Almirall, Amgen, Dr. Falk Pharma, Faes Pharma, Ferring, Janssen, MSD, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Takeda, Galapagos, Boehringer Ingelheim and Tillotts Pharma.

Míriam Mañosa: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and research consulting fees from AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, Tillotts Pharma, Faes Pharma, Gilead, Fresenius, Dr. Falk Pharma, Kern Pharma and Adacyte.

Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support, and consulting fees from AbbVie, MSD, Takeda, Ferring, Janssen, Pfizer, and Dr. Falk Pharma.

Manuel Barreiro-de Acosta: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from Pfizer, MSD, Takeda, AbbVie, Kern Pharma, Janssen, Fresenius Kabi, BMS, Ferring, Faes Pharma, Galapagos, Dr. Falk Pharma, Chiesi, Lilly, Adacyte and Tillotts Pharma.

Ana Gutiérrez: has received support for conference attendance, speaker fees, research support and consulting fees from AbbVie, MSD, Kern Pharma, Ferring, Faes Pharma, Amgen, Roche, Sandoz, Janssen, Pfizer, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma and Galapagos.

None of these activities by the authors were related to this study.

Francisco José Delgado, Mónica Millán, Isabel Alonso, Laura Camacho, Vanesa Gallardo, Ruth Serrano, Antonio Valdivia and Lourdes Pérez declare no conflicts of interest.

Marta Calvo Moya; Francisco Mesonero Gismero; Cristina Suárez Ferrer; Alejandro Hernández-Camba; Mariam Aguas Peris; Yago González-Lama; Mónica Millán Scheiding; Laura Camacho Martel; Ana Echarri Piudo; María Isabel Vera Mendoza; Yamile Zabana Abdo; Míriam Mañosa Ciria; Francisco Rodríguez-Moranta; Manuel Barreiro-de Acosta; Ana Gutiérrez Casbas.