Klebsiella pneumoniae, a common bacteria, is pathogenic in many nosocomial infections of the respiratory, urinary and gastrointestinal tract. However, liver abscess caused by K. pneumoniae (KLA) presents as an invasive syndrome, especially on the Asian continent. Described only in Taiwan in 1980, currently it extends throughout Southeast Asia in areas such as China (23%),1 Hong Kong (52%),2 South Korea (78.2%)3 and Taiwan (75%).1,3,4 It is a potentially serious syndrome due to its extrahepatic complications.

The reason for the higher prevalence of KLA in Asia is unclear. However it seems to be related to the virulence of the bacteria itself. KLA in Southeast Asia tends to be caused by K. pneumoniae strains, K1 or K2 capsular serotypes, associated with a phenotype of hypermucoviscosity and hypervirulence, compared to other non-Asian countries.1,4,5 Lin et al. suggest colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract by K. pneumoniae via the portal vein as the primary cause of the liver abscess,1 after isolating the bacteria in faeces from a healthy Chinese and foreign population residing in China. In recent years, the prevalence has increased in non-Asian patients (America, Europe and Australia) and also in Asians living in other countries due to migration. However, the literature is mainly in the form of case reports.6 In a series in the United States, 48% of patients were not Asian.4

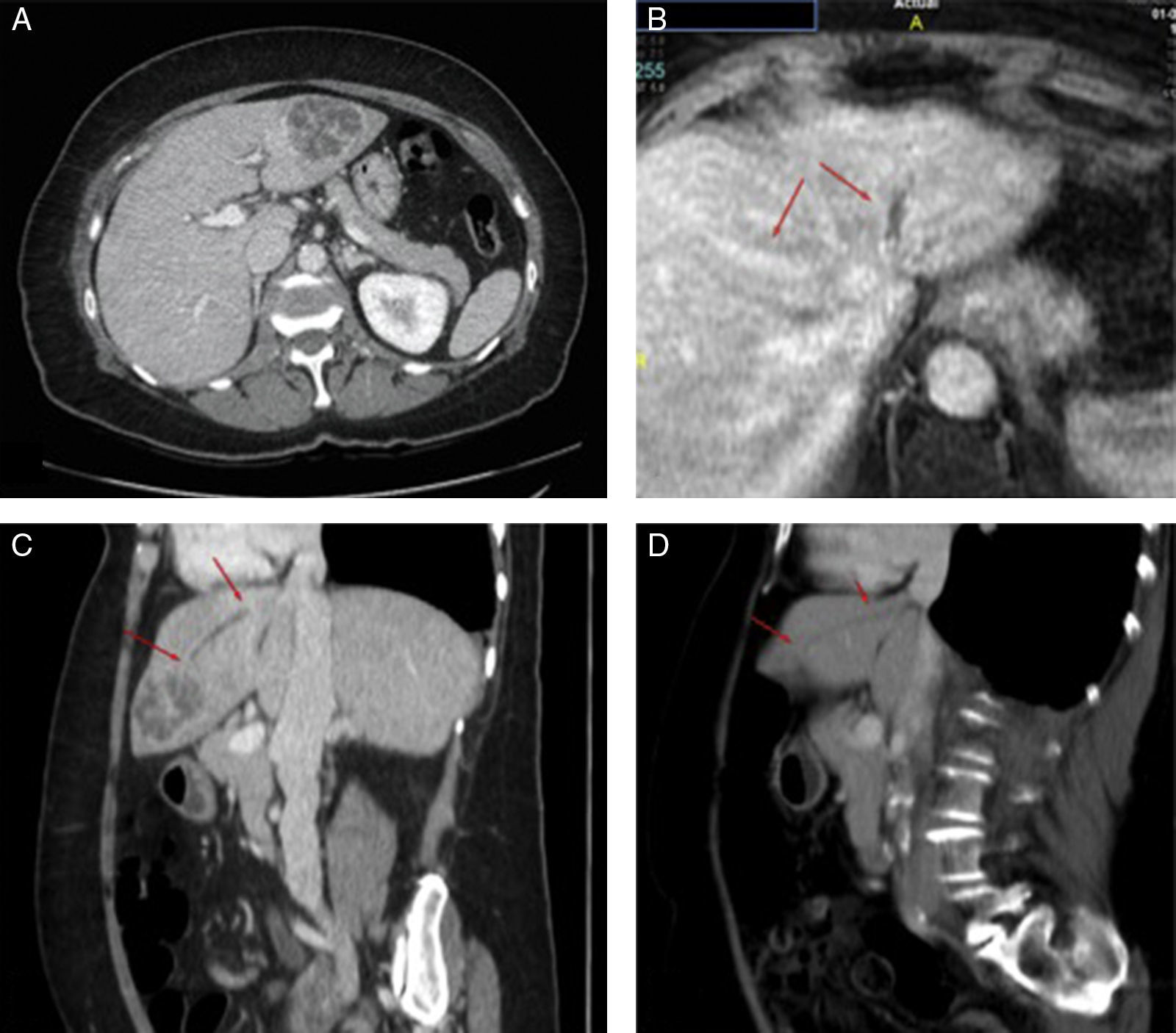

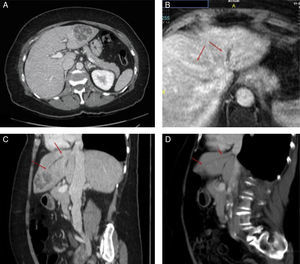

We present four diagnosed cases of KLA at our site (Table 1). The three cases of Chinese nationality had a mean age of 37 years, while the only Spanish woman was 71 years old. We consider it plausible that the Chinese nationality is predominant due to migration flows, and the probable mechanism of colonisation of the gastrointestinal tract, as mentioned before. The four cases came to the emergency department as a result of abdominal pain and fever. None had risk factors associated with KLA such as diabetes mellitus (DM) or immunosuppression, and none developed distant complications. In three of the four cases, the imaging study diagnosed a single multiloculated abscess. Contrary to the published information, the predominant location was in the left liver lobe.4 The Spanish patient had thrombophlebitis in the left hepatic vein (risk factor for extrahepatic complications). Even so, she did not develop a metastatic infection (Fig. 1). All were treated with percutaneous drainage and antibiotics with good results.

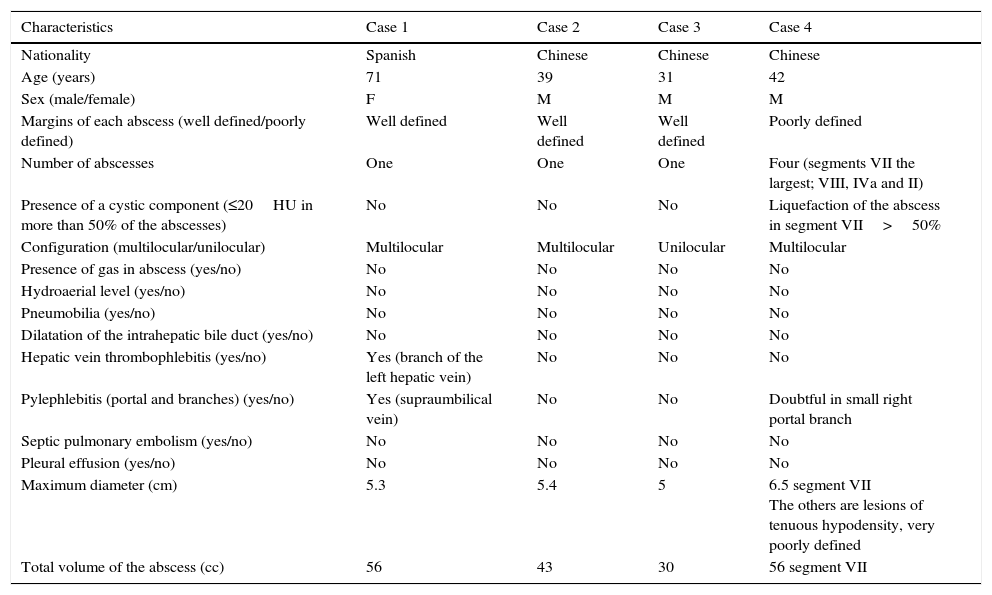

Clinical and radiological characteristics of the patients studied.

| Characteristics | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nationality | Spanish | Chinese | Chinese | Chinese |

| Age (years) | 71 | 39 | 31 | 42 |

| Sex (male/female) | F | M | M | M |

| Margins of each abscess (well defined/poorly defined) | Well defined | Well defined | Well defined | Poorly defined |

| Number of abscesses | One | One | One | Four (segments VII the largest; VIII, IVa and II) |

| Presence of a cystic component (≤20HU in more than 50% of the abscesses) | No | No | No | Liquefaction of the abscess in segment VII>50% |

| Configuration (multilocular/unilocular) | Multilocular | Multilocular | Unilocular | Multilocular |

| Presence of gas in abscess (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Hydroaerial level (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Pneumobilia (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Hepatic vein thrombophlebitis (yes/no) | Yes (branch of the left hepatic vein) | No | No | No |

| Pylephlebitis (portal and branches) (yes/no) | Yes (supraumbilical vein) | No | No | Doubtful in small right portal branch |

| Septic pulmonary embolism (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Pleural effusion (yes/no) | No | No | No | No |

| Maximum diameter (cm) | 5.3 | 5.4 | 5 | 6.5 segment VII The others are lesions of tenuous hypodensity, very poorly defined |

| Total volume of the abscess (cc) | 56 | 43 | 30 | 56 segment VII |

(A) Abdominal CT with diagnosis of liver abscess in segment II/III 5.3×4.8×4.4cm. (B) Abdominal MRI on which thrombophlebitis is identified in the left hepatic vein. With the two arrows the difference in left hepatic vein refill (thrombophlebitis) from the mean (normal) is marked. (C and D) Comparison between the diagnostic abdominal CT (C) and the abdominal CT two months after placement of the percutaneous drainage (D). The arrows indicate the trajectory of the thrombophlebitis in the left hepatic vein in the sagittal section. A marked reduction in the abscess is noted along with persistent thrombophlebitis in the left hepatic vein (arrows). In the follow-up ultrasound at 7 months, full resolution is confirmed.

Invasive KLA syndrome is characterised by its association with extrahepatic infection complications, especially endophthalmitis (with a high probability of blindness in diabetic patients4), septic pulmonary emboli, osteomyelitis, cerebral abscesses and necrotising fasciitis, which may require adjusting the dose of antibiotics. KLA is different from the usual pyogenic abscess as it is not related to cholangitis, and is usually associated with DM. In long series on KLA, around 40–78% had DM or glucose intolerance and 8–15% of these had serious distant infections.1,6,7 Poorly-controlled diabetic patients with HbA1c>9% had greater risk of presenting hepatic vein thrombophlebitis, gas production and distant infections, than non-diabetics or well-controlled diabetics.7 This is attributed to immune system changes, vasculopathy, neuropathy and metabolic disorders of the individual, which makes them more prone to infections.

Tissue hyperglycaemia and immunological changes foster a micro-environment that favours bacterial growth and gas production. The radiological finding of a large accumulation of gas is usually related to the size of the abscess and should be a sign of alarm for other possible distant infections. Wang et al. found that 72.7% of patients with distant infections had hepatic vein thrombophlebitis in the computed tomography (CT) and these findings were more common in the group with worse glycaemic control.7

Thrombophlebitis would explain the mechanism by which the pathogen passes into the bloodstream and later spreads, causing distant infections. This radiological sign could be an indicator of a possible extrahepatic infection. In accordance with this, none of our patients had DM or gas production within the abscess. KLAs are often single and multiloculated. They may also be associated with thrombophlebitis and/or portal and/or hepatic vein thrombosis, although the incidence of this is not well established.8

The aggression of this syndrome stems from various risk factors studied to date: magA, specific gene for the K1 capsular serotype, which increases resistance to phagocytosis; rmpA, gene that regulates the phenotype of hypermucoviscosity; aerobactin, an iron siderophore; and kfu, an iron uptake system.9,10 A positive spring test determines the hypervirulence phenotype (K1 and K2). This test is determined by the growth of colonies on agar plates in chains longer than 5mm.4

The treatment of choice is percutaneous drainage, guided by ultrasound or CT, along with antibiotic therapy (ampicillin-sulbactam, third-generation cephalosporins or quinolones).4,8

In conclusion, the clinical suspicion is essential to direct the study and not delay intravenous antibiotic therapy and percutaneous drainage. Keeping its virulence in mind, when K. pneumoniae is confirmed in blood cultures and/or abscess cultures, the capsular serotype should be identified (string test) and radiological signs with the greatest plausibility of spreading haematogenically should be identified, such as thrombophlebitis or gas production.

Please cite this article as: Pañella C, Flores-Pereyra D, Hernández-Martínez L, Burdío F, Grande L, Poves I. Absceso hepático primario por Klebsiella pneumoniae: una entidad en auge. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:525–527.