The use of immunomodulatory and biological drugs is associated with an increased risk of infection, including colonisation by opportunistic germs.1 Although most infections are viral and bacterial, they can also be caused by a wide spectrum of microorganisms, including fungi. We present a case of skin infection by Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans) in a patient with ulcerative colitis and pyoderma gangrenosum (PG).

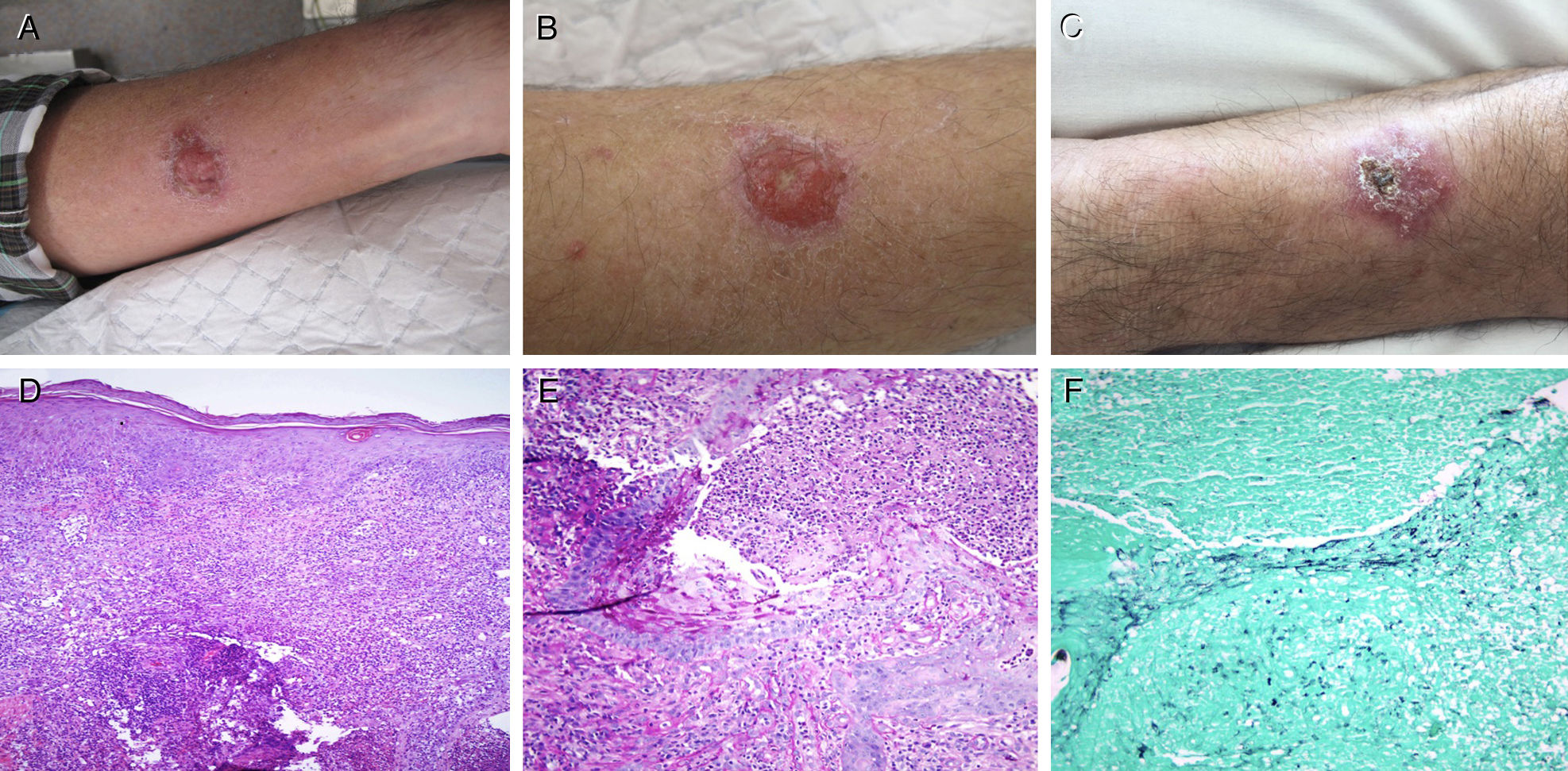

This was a 59-year-old male who owned hens and had pigeons within the vicinity of his home, diagnosed with ulcerative colitis (E2S2) in 2011. The disease was in remission under combined treatment with infliximab and azathioprine, which he had been taking since July 2015. In September of that year, he presented with two ulcerated lesions, one on each forearm, suggestive of PG. A histopathological study of the lesions confirmed the clinical suspicion, and infection by fungi and mycobacteria was ruled out by culture (in Sabouraud and Löwenstein media) and staining (haematoxylin–eosin, PAS and Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver). After treatment with prednisone, the PG on the left forearm resolved, but the right forearm lesion persisted, so oral ciclosporin was added. Given the patient's failure to respond despite quadruple immunosuppressive therapy (azathioprine, infliximab, prednisone and ciclosporin), a new biopsy was performed, with histological findings of PG, staining negative for fungi (Fig. 1), and a culture that grew C. neoformans. Disseminated cryptococcosis was ruled out (normal cranial CT, fundus examination and chest X-ray and negative culture for soluble antigens associated with C. neoformans in blood and cerebrospinal fluid). The lesion resolved after two weeks of intravenous amphotericin B and oral flucytosine, and four weeks of oral fluconazole. During the antifungal therapy, the immunosuppressive and biological therapy was suspended, maintaining oral mesalazine 3g/day.

(A) Pyoderma gangrenosum in the left forearm at diagnosis. (B) Ulcerated lesion on the right forearm with growth of C. neoformans in culture. (C) Cutaneous cryptococcosis on the right forearm, after antifungal treatment. (D) Haematoxylin–eosin stain 10×. (E) PAS staining 20×. (F) Grocott-Gomori stain 20×.

C. neoformans is an opportunistic fungus present in soil containing bird droppings (pigeons and hens). The infection is typically associated with immunocompromised individuals (HIV/AIDS, transplant recipients or patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy) and the main route of transmission is inhalation. Lung infection is usually asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals, while in immunocompromised patients the infection can spread through the bloodstream and may affect the central nervous system (meningoencephalitis), the skin or other organs, with a high risk of death. Diagnosis is made by detection of fungal growth in culture media (Sabouraud agar), by direct vision under a microscope (India ink staining of CSF), or by the identification of its soluble antigen in biological fluids. The most common histological stains may be used, such as haematoxylin–eosin, PAS and Grocott-Gomori methenamine silver, or more specific stains, such as Mayer's mucicarmine (stains the capsule of the fungus magenta) and Fontana-Masson stain (stains melanin reddish-brown).2

Two forms of skin manifestations of C. neoformans infection have been described. Primary cutaneous cryptococcosis is caused by superinfection of a previous, usually isolated lesion on exposed areas of the skin. It is similar to PG in appearance, and systemic involvement is uncommon. Skin involvement secondary to haematogenous spread usually involves multiple lesions in both exposed and unexposed areas. The lesions appear as umbilicated papules and are accompanied by systemic symptoms. Irrespective of the appearance or characteristics of the skin lesions associated with C. neoformans infection, systemic disease must always be ruled out.3

C. neoformans infections have been described in patients with IBD4 but no cases of PG and primary cutaneous cryptococcosis have been reported in any such patient. Given the high sensitivity of the culture, we believe that C. neoformans infected a previous PG lesion on the right forearm, although the possibility that a low concentration of cryptococci in the area chosen for the first biopsy precluded their detection in the initial culture cannot be completely ruled out. By the time the second biopsy was taken, cryptococci had multiplied due to the immunosuppressive action of prednisone and ciclosporin.5 Either way, the practical conclusion is that before adding further immunosuppressants in patients with IBD, biopsy of PG lesions refractory to standard treatment should be repeated (histology, staining and culture) to rule out fungal and bacterial infections.

Please cite this article as: Fraile López M, de Francisco R, Pérez-Martínez I, García García B, Vivanco Allende B, Asensi V, et al. Pioderma gangrenoso y criptococosis cutánea primaria en un paciente con colitis ulcerosa. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:107–108.