Lynch syndrome is the most common form of hereditary colorectal cancer (CRC) (0.9%–2%). It has an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance with high penetrance (80%), and is characterized by the early development of CRC, with distinctive features with respect to sporadic CRC (more common in the right colon, synchronous or metachronous neoplasms and lymphocytic infiltration). Lynch syndrome is associated with tumours in other locations (endometrium, ovary, stomach, small intestine, bile ducts, pancreas, urinary tract, skin and brain). Pathogenically, it is associated with alterations in the DNA mismatch repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 and PMS2), with mutations accumulating in highly repetitive DNA fragments called microsatellites. In addition, tumours in these patients show loss of expression of the protein corresponding to the germline mutation (detectable by immunohistochemistry [IHC]). The strategy for identifying patients with Lynch syndrome is based on the fulfilment of clinical criteria (revised Bethesda guidelines) and/or study of the DNA repair system in the tumour (by IHC for DNA repair proteins or microsatellite instability study). When these alterations are present, suspicion should be confirmed by studying the germline mutation in the DNA repair genes in peripheral blood. Once the causal mutation has been identified, first-degree relatives of carriers of the mutation can be tested for the mutation if they wish. Most cases are due to mutations in genes MSH2 (38%) and MLH1 (59%), and a small proportion in MSH6 and PMS2.1,2

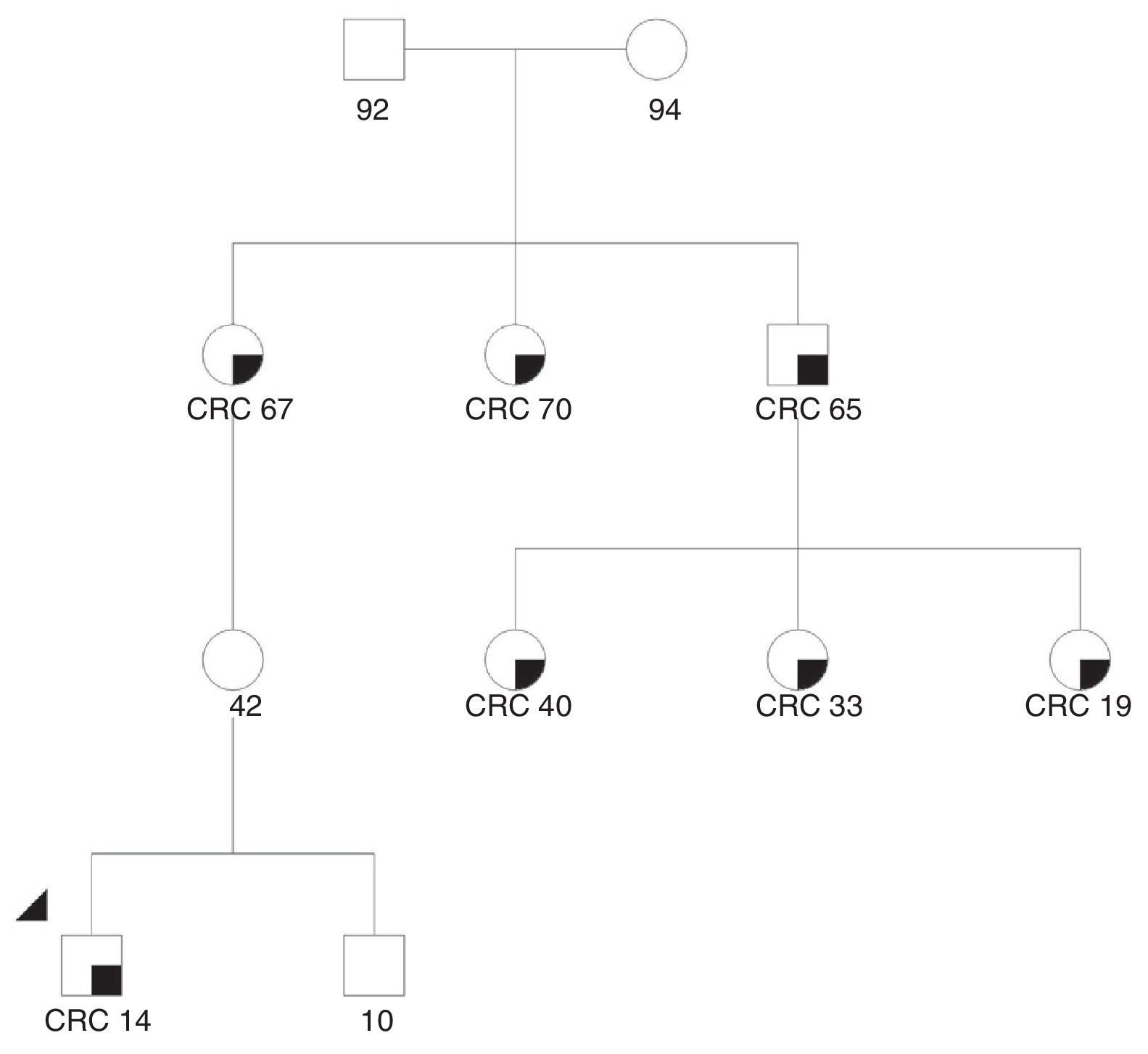

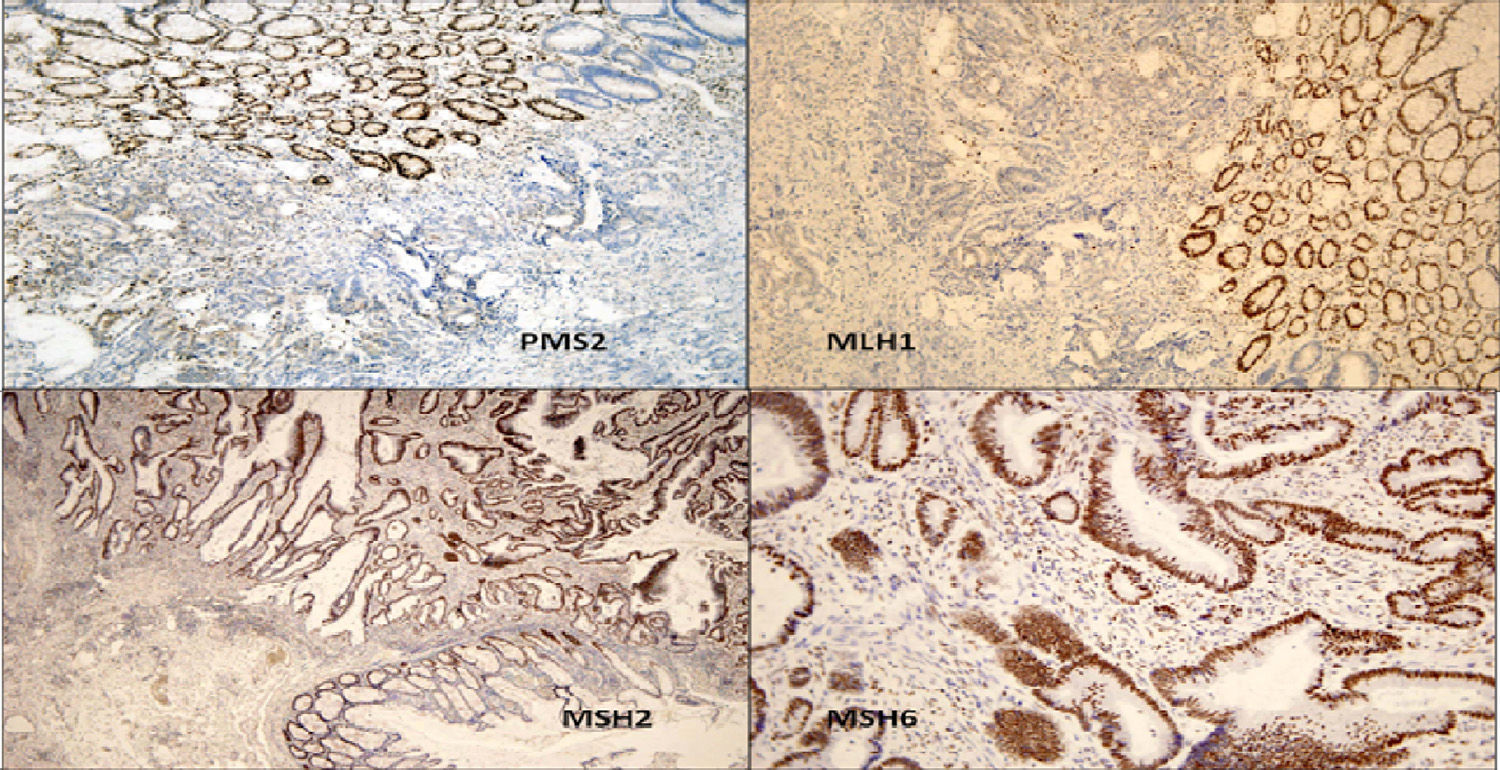

We present the case of a 14-year-old Paraguayan boy with a family history of colon cancer (Fig. 1): his grandmother and 2 siblings had the disease. He was admitted for chronic, bloody diarrhoea. Colonoscopy showed a tumour in the proximal rectum, which on biopsy turned out to be an adenocarcinoma. An extension study with magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography delimited a 6×6cm mass infiltrating the posterior wall of the bladder, with no evidence of metastasis. The patient underwent neoadjuvant radio- and chemotherapy followed by surgery, with total resection of the mesorectum and posterior wall of the bladder. The macroscopic specimen showed ulcerated infiltrating adenocarcinoma invading the outer muscle layer of the bladder, with mucosecretory differentiation, intact mesorectal fascia, 12 negative lymph nodes and absence of vascular and perineural invasion. The patient underwent adjuvant treatment with oxaliplatin and capecitabine. An IHC study for MLH1/MSH2/MSH6/PMS2 in the patient's tumour detected loss of expression of the proteins MLH1 and PMS2 in the tumour cells (Fig. 2). A genetic study confirming Lynch syndrome was not performed as the patient returned to his country of origin. After 58 months of follow-up, he is disease free. To date, 3 daughters of a great-uncle have been diagnosed with CRC, all aged under 40 years.

Immunohistochemical study to detect expression of the proteins associated with DNA repair genes: loss of expression of PMS2 and MLH1 in the tumour cells can be seen, while the normal mucosa retains nuclear expression of both proteins. MSH2 and MSH6 are positive in the tumour and in the normal mucosa.

The diagnosis of Lynch syndrome is a challenge in clinical practice. After a suspected diagnosis based on symptoms and study of the DNA repair genes in the tumour, diagnosis is confirmed by the presence of germline mutations in these genes and at-risk relatives can screened.3 However, genetic analysis seldom forms part of routine clinical practice, and interpretation of results can be complex. The study and follow-up of these patients in specialized genetic counselling units is therefore recommended. Endoscopic screening (colonoscopies every 1–2 years) can focus on members who carry the causal mutation, in order to identify precursor lesions or early-stage carcinomas. Chromoendoscopy has been shown to increase the detection of lesions in patients with Lynch syndrome.4

We were unable to find any reported cases of hereditary CRC in such young patients in the literature. In the case described in this report, differential diagnosis with constitutional mismatch repair deficiency syndrome, defined by the presence of biallelic mutations in DNA repair genes, could have been an option. However, the absence of cases in the paternal branch, normal expression of MLH1/PMS2 in normal mucosa, and absence of other manifestations (café au lait spots, haematological tumours) all but ruled out this syndrome.5 In this family, therefore, we believe that Lynch syndrome due to a mutation in MLH1is the most likely diagnosis. If the suspected diagnosis is confirmed, endoscopic screening of at-risk relatives should start at 10 years of age. Similarly, endometrial and extra-colonic neoplasm screening should also be performed according to the familial predisposition for a particular type of tumour. Treatment of colorectal tumours in these patients is extensive surgical resection to prevent metachronous neoplasms, with subsequent endoscopic follow-up every 1–2 years. Tumours in patients with Lynch syndrome are associated with a better prognosis, which could explain the long disease-free survival, despite being a locally advanced tumour.

Please cite this article as: Santos Santamarta F, Arenal Vera JJ, Sánchez Ocaña R, Tinoco C, Torres MA, Citores MA, et al. Neoplasia maligna de recto en paciente adolescente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:239–240.