Ulcerative colitis (UC) is an intermittent chronic pathology of the colon characterised by continuous inflammation of the mucosa that affects the rectum and, subsequently, the rest of the colon. Various cytokines (interleukin [IL]-12, tumour necrosis factor [TNF]-α, interferon-γ, IL-23) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of UC.1 Selective targeting of pro-inflammatory cytokines with biological therapies is the main therapeutic approach. The recent UNIFI study has shown ustekinumab to be useful for inducing remission and maintenance in patients with UC.2 Ustekinumab is a human monoclonal antibody that binds to the shared p40 protein subunit of IL-12 and IL-23, and it has been found to be useful as rescue therapy in refractory patients. We present a case of UC treated with ustekinumab in combination with cyclosporine as rescue therapy.

A 42-year-old woman was diagnosed with steroid-dependent UC pancolitis in 2012. Initially, she developed an acute pancreatitis secondary to azathioprine. She started infliximab but due to a secondary failure, was replaced by adalimumab.

After one year, the patient presented an outbreak with osteoarticular symptoms, leading to the withdrawal of adalimumab and the start of golimumab, with subsequent loss of response and severe endoscopic activity. Vedolizumab was started and clinical remission was achieved during 3 years.

A severe UC outbreak caused the initiation of tofacitinib, but it was withdrawn due to the appearance of dyspnoea and cough, suspecting a pulmonary thromboembolism, which was subsequently ruled out. After ceasing treatment, a severe outbreak required intravenous steroid therapy and admission. A colonoscopy showed a severe flare, with UCEIS of 7. Colectomy was recommended due to steroid resistance and patient's status, but the patient dismissed the surgical option.

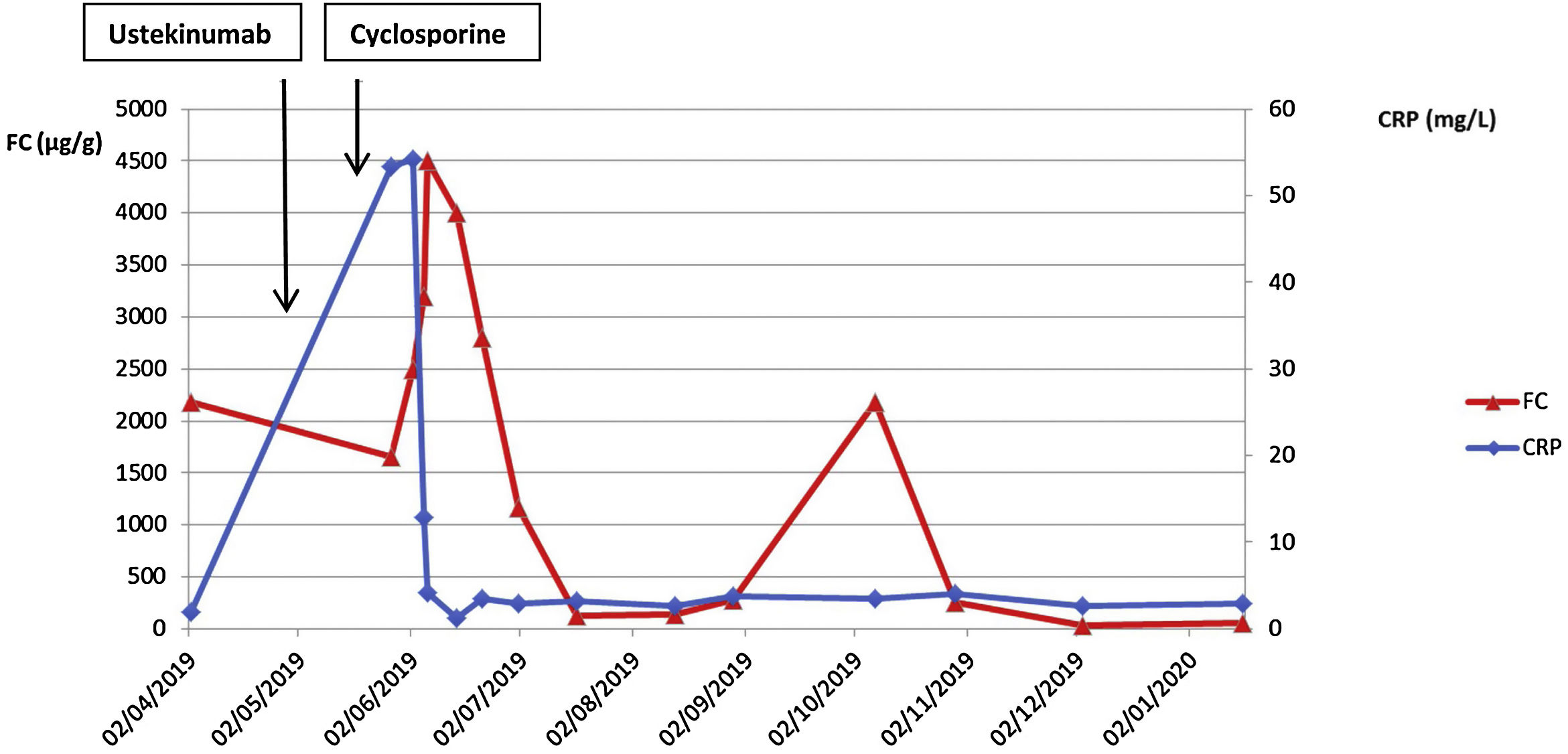

Finally, an intravenous induction dose of 6mg/kg of ustekinumab was administered. Five days after induction, no clear improvement had occurred (Fig. 1). Due to steroid resistance, previous failure of anti TNF drugs and knowing that studies had reported ustekinumab results appeared at week 8,2 we started oral cyclosporine (4mg/kg/12h) as a rescue therapy. An early clinical response was observed with an acute drop in inflammatory parameters (Fig. 1). The patient was discharged 10 days after starting cyclosporine. Cyclosporine was removed progressively, reducing by 100mg every 2 weeks until the steroids were completely tapered. The second dose of ustekinumab was administered the same day the patient finished the steroids, 8 weeks after the induction, achieving FC normalisation. From that moment on, cyclosporine was tapered by 50mg every week, and its removal was coincident with the third dose of ustekinumab (ustekinumab levels before this third dose were 1.8μg/ml). Four weeks later, while on monotherapy, she presented a clinical worsening and FC began to rise. Given the levels of ustekinumab were in the low range and the available evidence about the need and efficacy of ustekinumab treatment intensification,3 we reintroduced 6mg/kg intravenous ustekinumab and intensified maintenance treatment to every 4 weeks. The aim was to attempt to keep ustekinumab for maintenance. Eight weeks after intensification, the patient reached clinical remission, ustekinumab levels of 15 mcg/l and normalisation of the inflammatory parameters (CRP 2.7mg/l and FC 36.2μg/g). One year after starting ustekinumab, the patient is asymptomatic, FC 22μg/ml, ustekinumab levels of 7.9mcg/ml, and mucosal healing.

Some recent studies have shown that ustekinumab is a safe and effective treatment option for refractory moderate-to-severe UC.2,4 The UNIFI study had determined that ustekinumab reaches a clinical response of 57.2% at week 8 of administration of an intravenous induction dose of 6mg/kg.2 Here we present a clinical case in which ustekinumab was used for a steroid-resistant severe flare of UC that had previously failed multiple therapies. There is little evidence in clinical practice on the efficacy of ustekinumab in such an acute flare.5

With this case we suggest that achieving remission requires higher levels of ustekinumab, at least in these refractory situations. Similarly, we should note that combined therapies can be taken into consideration, especially when severe situations arise, such as steroid resistance in a multi-failure scenario. We hypothesise that the inflammatory burden could be limiting the response to drugs. In this scenario, the need for combined therapies that could affect various immunological pathways concomitantly, could be an option to facilitate consistent drug efficacy but also prevent a therapeutic line loss.