To study the multidisciplinary management of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and perianal disease (perianal Crohn's disease, PCD), as well as to analyse a possible relationship between the recurrence of perianal symptoms, the type of fistula and the treatment used.

Patients and methodsDescriptive, retrospective study of patients with PCD who were treated in the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Unit. Epidemiological, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic variables were collected, as well as clinical outcome and response to treatment.

ResultsOf the 300 patients who attended the outpatient clinic at a university hospital, 65 had PCD. Sixteen simple fistulas (24.6%) and 49 complex fistulas (75.4%) were diagnosed. The most commonly used diagnostic technique was the endoanal ultrasound (45%). Antibiotics were used in 77.4% of patients, and 70% needed anti-TNF therapy to manage the PCD. Surgery was performed on 75.4% of the patients overall. PCD recurred in 41.5% of cases, requiring a change of the biological drugs administered and/or surgery. Complex fistulas were more likely to require surgery (p=0.012) and recurrence of PCD was also more common with complex fistulas (p=0.036).

ConclusionManagement of PCD must be multidisciplinary and combined. Most patients with complex PCD require treatment based on biological drugs. Despite therapy, remission of perianal symptoms is not achieved in a percentage of patients, supporting the need to develop new therapies for refractory cases.

Estudiar el manejo multidisciplinar de los pacientes con enfermedad de Crohn (EC) y enfermedad perianal (EPA) asociada y analizar la posible relación entre la recidiva de la sintomatología perianal, el tipo de fístula y los tratamientos empleados.

Pacientes y métodosEstudio retrospectivo descriptivo en pacientes con EPA asociada a la EC seguidos en la Unidad de Enfermedad Inflamatoria Intestinal. Se recogieron variables epidemiológicas, clínicas, diagnósticas y terapéuticas, la evolución clínica y respuesta a los tratamientos administrados.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 65 pacientes con EC y EPA de los 300 pacientes controlados en consulta externa de un hospital universitario. Se diagnosticaron 16 fístulas simples (24,6%) y 49 fístulas complejas (75,4%). La técnica diagnóstica más empleada fue la ecografía endoanal (45%). Se utilizaron antibióticos en el 77,4% de los pacientes y el 70% precisaron utilización de un fármaco anti-TNF para el control de la EPA. Se realizó cirugía en el 75,4% del conjunto de la muestra. La EPA recidivó en el 41,5% precisando cambio de fármaco biológico y/o cirugía. Las fístulas complejas necesitaron con más frecuencia tratamiento quirúrgico (p=0,012) y la recidiva de la EPA fue más frecuente en las fístulas complejas (p=0,036).

ConclusiónLa mayor parte de los pacientes con EC y EPA compleja necesita tratamiento con fármacos biológicos. El manejo de la EPA deber ser multidisciplinar y combinado. Sin embargo, hay un porcentaje de casos en los que no se consigue la remisión de la clínica perianal lo que justifica el desarrollo de nuevas terapias para los casos refractarios.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic systemic disorder affecting the gastrointestinal tract in which complications may appear in the perianal area. This is seen in approximately a third of patients with Crohn's disease (CD). Perianal lesions may constitute a complication of IBD or even appear before IBD is diagnosed. They are responsible for significant morbidity in these patients. Perianal Crohn's disease (PCD) manifests in the form of fissures, fistulas, abscesses, skin flaps and ulcers.1 Fistulas may be classified as simple or complex, according to a classification proposed by Sandborn in 2003.2 According to this classification, a fistula may be complex either due to the origin of the fistula tract (high intersphincteric, high trans-sphincteric, extrasphincteric or suprasphincteric) or due to multiple external openings, pain, fluctuation or anal stenosis. Rectovaginal fistulas and fistulas with inflammatory activity on rectoscopy are also considered complex. Diagnostic methods include endoanal ultrasound, pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (pMRI) and perianal examination under anaesthesia. The latter is considered the gold-standard diagnostic tool in the assessment of PCD.1 In recent years, new treatment methods have been developed to manage PCD. This should be personalised and combined, and overly aggressive surgical manoeuvres should be avoided.

The objective of this study was to analyse the characteristics of PCD in the patients at our centre, the treatments used and the response to these treatments. The management of recurrence and its possible association with the baseline characteristics of the patients and with the treatments used were analysed as well.

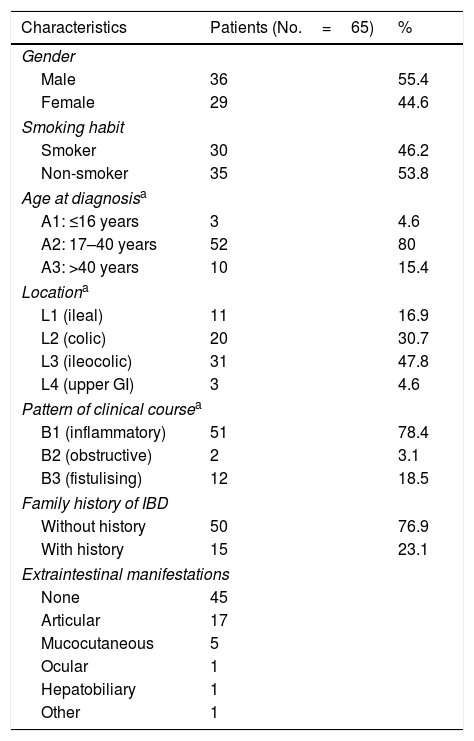

MethodsA retrospective review was conducted of all cases of patients with PCD associated with CD from 2004 to June 2016 followed up at a secondary university hospital in Madrid caring for a population of around 225,000 inhabitants, a significant percentage of whom are patients under 40 years of age (Table 1). Treatment decisions were made by consensus at regular meetings of the IBD medical–surgical committee involving gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons and radiologists specially dedicated to IBD.

Demographic characteristics of the study patients.

| Characteristics | Patients (No.=65) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 36 | 55.4 |

| Female | 29 | 44.6 |

| Smoking habit | ||

| Smoker | 30 | 46.2 |

| Non-smoker | 35 | 53.8 |

| Age at diagnosisa | ||

| A1: ≤16 years | 3 | 4.6 |

| A2: 17–40 years | 52 | 80 |

| A3: >40 years | 10 | 15.4 |

| Locationa | ||

| L1 (ileal) | 11 | 16.9 |

| L2 (colic) | 20 | 30.7 |

| L3 (ileocolic) | 31 | 47.8 |

| L4 (upper GI) | 3 | 4.6 |

| Pattern of clinical coursea | ||

| B1 (inflammatory) | 51 | 78.4 |

| B2 (obstructive) | 2 | 3.1 |

| B3 (fistulising) | 12 | 18.5 |

| Family history of IBD | ||

| Without history | 50 | 76.9 |

| With history | 15 | 23.1 |

| Extraintestinal manifestations | ||

| None | 45 | |

| Articular | 17 | |

| Mucocutaneous | 5 | |

| Ocular | 1 | |

| Hepatobiliary | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease; GI: gastrointestinal.

Fistulas were classified as simple or complex according to Sandborn's classification.2 If a patient had a simple fistula and a complex fistula at the same time, his or her fistulas were classified as complex fistulas.

The following variables were collected by reviewing electronic medical records:

Qualitative variablesEpidemiological: sex, smoking habit, family history of IBD.

Clinical: IBD type, location and pattern of progression of bowel disease according to the Montreal classification,3 other non-bowel signs, date of diagnosis of IBD and PCD, fistula type and associated perianal abscess.

Initial diagnostic methodTherapeutic: antibiotic treatment (metronidazole, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin), immunomodulators (azathioprine or mercaptopurine), biologic drugs (infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab pegol).

Clinical course and response to treatments administered: Complete response was defined as closure of the fistula opening and cessation of drainage in all fistulas. Partial response was defined as a decrease at least 50% of fistulas. Clinical indicators were monitored and, in some cases, pMRI or endoanal ultrasound was performed to evaluate response.

Quantitative variablesAge, time since diagnosis of luminal disease, number of fistulas, posology of medical treatment and number of surgeries.

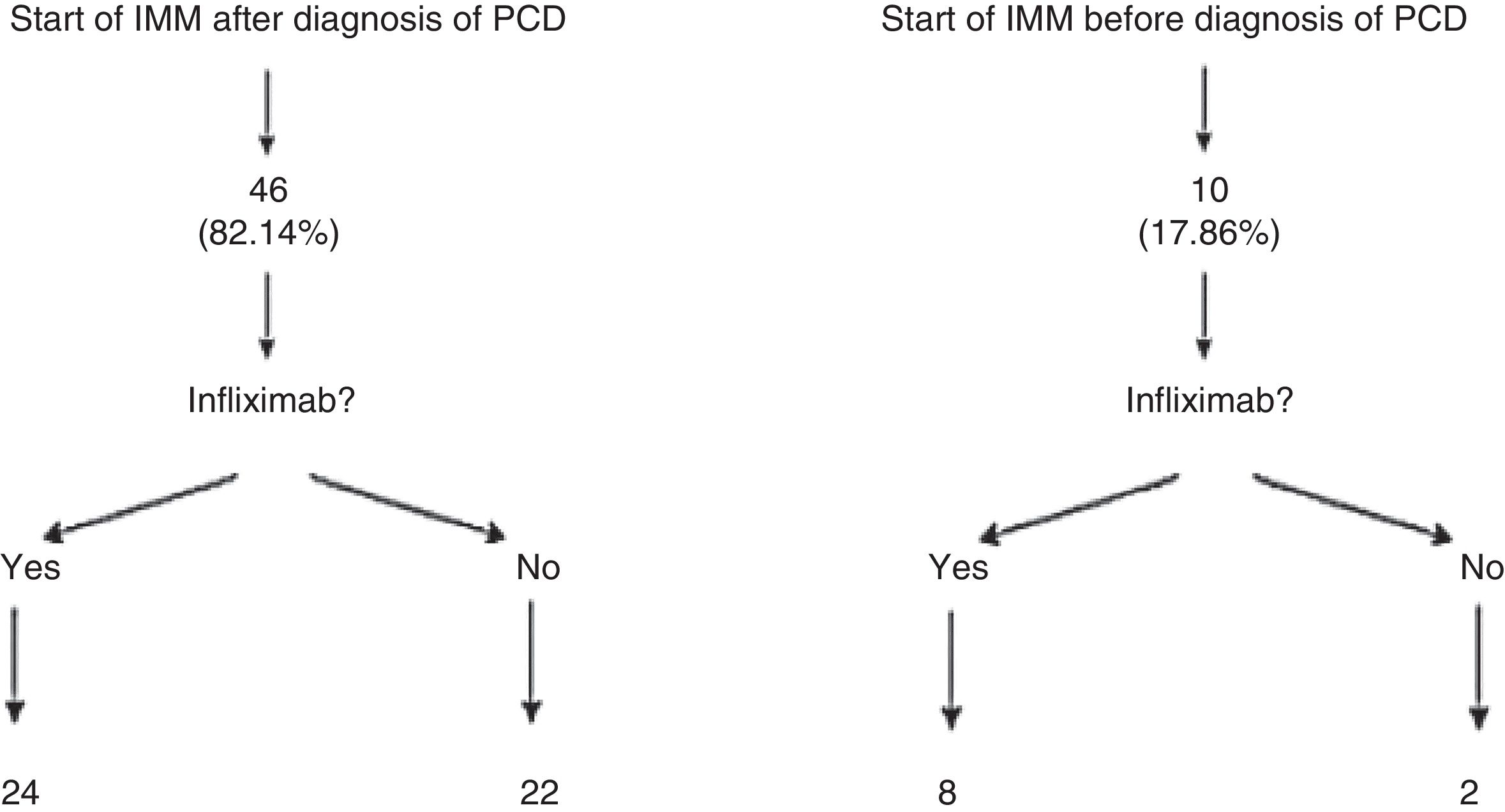

The clinical course of PCD was analysed in patients who started treatment with immunomodulators after being diagnosed with PCD and in patients who were already receiving immunomodulator treatment before developing a perianal event. Response following administration of anti-TNF biologic drugs was analysed as well. In patients who had a recurrence of PCD, the treatments that they had been administered and their baseline clinical characteristics were reviewed.

The data obtained were analysed using the SPSS statistical program. Qualitative variables were expressed in terms of frequencies and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Quantitative variables were represented in terms of mean±standard deviation if the variable had a normal distribution or median and interquartile range if it did not. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to evaluate the normality of the continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared test. Quantitative and qualitative variables with 2 categories were compared using Student's t test (when the variable had a normal distribution) or the Mann–Whitney U test (when it did not). Quantitative and qualitative variables with 3 or more categories were compared using analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal–Wallis non-parametric test. A multivariate analysis using logistic regression was performed to identify possible risk factors related to a recurrence of PCD. A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

ResultsOut of a total of 300 patients with CD managed on the IBD unit at our centre, 65 patients with CD and PCD were enrolled. The prevalence of PCD in our patients with CD was 22% (95% CI: 17.1–26.8). Table 1 shows the baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients enrolled in the study.

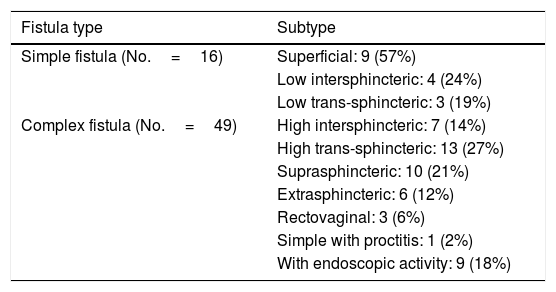

Mean time to diagnosis of PCD was 43±63 months following diagnosis of CD, and diagnosis of the fistula preceded diagnosis of luminal disease in 8 patients (12.1%). In total, 16 simple fistulas (24.6%) and 49 complex fistulas (75.4%) were diagnosed (Table 2).

Classification of perianal fistulas.

| Fistula type | Subtype |

|---|---|

| Simple fistula (No.=16) | Superficial: 9 (57%) |

| Low intersphincteric: 4 (24%) | |

| Low trans-sphincteric: 3 (19%) | |

| Complex fistula (No.=49) | High intersphincteric: 7 (14%) |

| High trans-sphincteric: 13 (27%) | |

| Suprasphincteric: 10 (21%) | |

| Extrasphincteric: 6 (12%) | |

| Rectovaginal: 3 (6%) | |

| Simple with proctitis: 1 (2%) | |

| With endoscopic activity: 9 (18%) |

At our centre, the most common initial technique was endoanal ultrasound (45% of cases) performed by colorectal surgeons, followed by pMRI with 36.7% and examination under anaesthesia with 18.3%. In complex fistulas (49 patients), a second technique was performed in 37 patients (to place a seton, or to perform pMRI to complete the study).

A perianal abscess associated with the diagnosis and requiring drainage was also present in 79% of cases.

Regarding the medical treatment used, overall, 77.4% (95% CI: 65.9–87.9) of patients received the antibiotics metronidazole, ciprofloxacin and/or levofloxacin as a complementary treatment, and improvement of perianal symptoms was seen in 97.5; 89.5% and 87.5%, respectively.

Patients who presented frequent or early relapses (despite improvement on antibiotics) or had complex fistulas underwent surgical treatment, immunosuppressive treatment with thiopurines (azathioprine or mercaptopurine) and/or anti-TNF treatment. In our sample, 56 patients (84.8%; 95% CI: 76.9–95.3) required immunomodulators; 46 of them did so following diagnosis of PCD, whereas the remaining 10 had started azathioprine or mercaptopurine before developing the perianal event. It is important to note that 24 of the 56 patients treated with immunomodulators did not need to start treatment with a biologic drug. Among those 24 cases, 16 complex fistulas (32.6%) were found (Fig. 1).

Anti-TNF biologic drugs were used to treat PCD in fistulas that did not respond to other treatments, in fistulas in which other treatments caused toxicity or intolerance and in complex fistulas with a high risk of sphincter destruction and secondary incontinence. At our centre, biologic drugs were used to treat PCD in 34 of the 49 complex fistulas: 69.4%; 95% CI: 55.5–83.3.

The first-line biologic drug was infliximab, used in 32 of the 34 patients. Fourteen patients (43.7%) achieved a complete response; 6 (18.7%) achieved a partial response and 12 (37.5%) achieved no response. In 9 of the cases with no response to infliximab, a decision was made to switch to another anti-TNF drug, adalimumab; 4 of those 9 patients achieved a complete response. Regarding the management of the remaining 5 cases, 2 patients started treatment with vedolizumab (one did not respond and therefore underwent end ileostomy). One patient had to stop adalimumab following a diagnosis of breast cancer and required bowel resection (and colostomy). Another patient started treatment with methotrexate due to the onset of extraintestinal manifestations, predominately articular, with maintenance of a seton and slight suppuration. The last patient died following a complication subsequent to surgery for intestinal fistulas in a context of serious abdominal sepsis after having been lost to follow-up for several years.

Regarding surgical treatment, surgery was performed in 49 of the 65 patients with perianal fistulas (75.4%; 95% CI: 64.1–86.7). The most common surgical technique was cleansing of the tract and placement of a seton (77.5%). In most cases (73.7%) the seton was maintained for more than 12 months (in 21% it was maintained for less than 3 months and in 5.3% it was maintained for 3–6 months). Following surgery, a complete response was achieved in 93.7% of simple fistulas. Of the patients with complex fistulas who underwent surgery, 65.3% had a complete response (it should be noted that approximately 3 out of every 4 patients who responded to surgical treatment were being treated with an anti-TNF drug).

Regarding radiological response following treatment, response was evaluated with pMRI in 13 patients and with endoanal ultrasound in 23 patients.

In our entire sample, 27 patients (41.5%; 95% CI: 28.8–54.3) had a recurrence of their PCD. Therapeutic management of recurrence consisted of placing a seton in 59.2%, a combination of placing a seton and intensifying biologic drug treatment in 25.9% and intensifying anti-TNF drug treatment alone in 14.8%. Finally, following personalised medical–surgical treatment, the overall clinical response of the patients was analysed against their PCD. Complete clinical response was reported in 78.7%, partial clinical response was reported in 14.8% and no response was reported in 6.6%. A bivariate analysis compared the probability of requiring surgery based on fistula type and found that patients with complex fistulas required surgical treatment more often (p=0.012). The most common surgical treatment overall was cleansing of the fistula tract and placement of a seton. In addition, a multivariate analysis using logistic regression was performed to identify risk factors associated with the development of recurrence. This showed that recurrence of PCD was more common in complex fistulas (p=0.036). Gender, smoking habit, age at diagnosis, location of luminal disease and behaviour thereof showed no influence in this model. In addition, there were no differences between smokers and non-smokers.

DiscussionAt present, due to the complexity and heterogeneity of patients with CD and PCD, diagnosis and treatment thereof should be multidisciplinary, involving gastroenterologists and colorectal surgeons specially dedicated to managing patients with CD. In our experience, having a committee with regular meetings in which these patients are evaluated according to the most up-to-date scientific evidence is very useful in management by consensus of these patients.

pMRI is an excellent method, although if there is no rectal stenosis then endoanal ultrasound is a good alternative in expert hands due to its accessibility.4 A recent meta-analysis reported that endoanal ultrasound and pMRI had the same sensitivity (87%) but different specificities (43% for endoanal ultrasound, 59% for pMRI). pMRI not only is a less operator-dependent test, but also may identify clinically silent abscesses and inflammation.5 Computed tomography and fistulography have been replaced by the above-mentioned techniques due to their lower diagnostic sensitivity. Examination under anaesthesia is the gold standard for diagnosis of perianal fistulas. It not only has high specificity (close to 90%), but also enables treatment in the affected area. A combination of examination under anaesthesia and endoanal ultrasound achieves a specificity close to 100%.6 In our series, nearly half of patients underwent an initial study using endoanal ultrasound since this is a more accessible, cost-effective method that may be performed shortly after it has been indicated. Moreover, it should be noted that a simple fistula with activity on rectoscopy should be considered and treated as a complex fistula. Therefore, this test is mandatory in all patients. Our sample, due to its limited number of cases, featured just one case of a simple fistula with proctitis which required anti-TNF treatment.

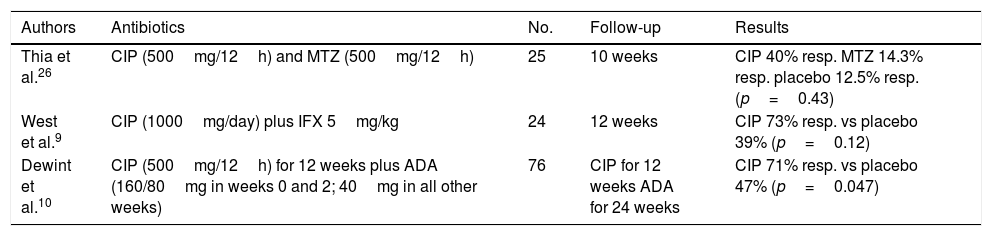

More than three-quarters of our patients received antibiotics in the initial management of their PCD. The use of antibiotics with no other adjuvant treatment is not indicated at present5 and, although the effectiveness of antibiotics in PCD has not been evaluated in studies with a high level of evidence, some series have demonstrated their benefit in the treatment of this disease, as shown in Table 3. Ciprofloxacin and metronidazole form part of first-line treatment and improve perianal symptoms, thereby decreasing fistula suppuration and pain (RR=0.8; 95% CI: 0.66–0.98).7 The standard dose of ciprofloxacin is 500mg/12h. Regarding metronidazole, doses of up to 1000mg/day are normally used. Most adverse effects related to antibiotic treatment are mild and linked to gastrointestinal intolerance. In general, they do not require suspension of treatment. The duration of treatment with antibiotics is a matter of controversy; some studies have suggested that it should be 8–12 weeks.8 At our centre, most patients had initially received treatment with ciprofloxacin, metronidazole and/or levofloxacin at the usual doses and had achieved clinical improvement with fistula drainage decreasing or ceasing altogether, at least temporarily. This is consistent with the few studies published to date. Levofloxacin could play a role in symptom management—in a single dose vs 2 doses of ciprofloxacin—as we report in our experience. Therefore, we believe that levofloxacin could be included in future research as a study objective. For the moment, there is limited evidence establishing the differences between the antibiotics administered in PCD and the optimum combination of antibiotics, immunomodulators and biologic drugs to achieve management of perianal signs and symptoms. Evaluation with an imaging test such as pMRI could aid in selecting those cases which require scaling treatment. A combination of antibiotics and anti-TNF drugs (ciprofloxacin with infliximab9 and ciprofloxacin with adalimumab10) achieves responses in up to 70%–73%. These rates are superior to those achieved with the administration of an anti-TNF drug in monotherapy. Antibiotics are often used in patients with PCD who undergo placement of a seton.5

Studies published on antibiotic treatment in fistulising Crohn's disease.

| Authors | Antibiotics | No. | Follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thia et al.26 | CIP (500mg/12h) and MTZ (500mg/12h) | 25 | 10 weeks | CIP 40% resp. MTZ 14.3% resp. placebo 12.5% resp. (p=0.43) |

| West et al.9 | CIP (1000mg/day) plus IFX 5mg/kg | 24 | 12 weeks | CIP 73% resp. vs placebo 39% (p=0.12) |

| Dewint et al.10 | CIP (500mg/12h) for 12 weeks plus ADA (160/80mg in weeks 0 and 2; 40mg in all other weeks) | 76 | CIP for 12 weeks ADA for 24 weeks | CIP 71% resp. vs placebo 47% (p=0.047) |

ADA: adalimumab; CIP: ciprofloxacin; IFX: infliximab; MTZ: metronidazole; resp: response.

Thiopurines (azathioprine and mercaptopurine) were the most commonly used immunosuppressant drugs in our patients with PCD. Their most common side effect is gastrointestinal discomfort. They may also cause bone marrow toxicity, infections and pancreatitis. In some cases, these call for stopping the drug and require clinical and laboratory monitoring. There are no studies with the primary objective of evaluating the effectiveness of these immunomodulators in PCD. Some studies, including a meta-analysis by Pearson et al.,11 have concluded that thiopurines are an effective treatment in induction of remission and maintenance. When data collection was performed for this study, the most recent ECCO consensus had been published in 201012 and had been based on the conclusions of those studies.

They recommended using azathioprine or mercaptopurine as a first-line treatment in patients with complex fistulas and leaving anti-TNF drugs as second-line treatments. Therefore, many of our patients started treatment with azathioprine before starting treatment with a biologic drug based on the evidence at that time.

In the statistical analysis that we performed in our patients, we wished to distinguish between those who were already receiving immunomodulators before the perianal event and those who started it after they were diagnosed with PCD (Fig. 1). This analysis by subgroups was performed in the ACCENT I study13 since in daily clinical practice it is not uncommon for patients on immunomodulators for their luminal disease to start some time after they develop perianal events. In our opinion, this may represent a source of significant bias in data analysis and extrapolation.

Most of our patients with CD and complex PCD required treatment with biologic drugs to manage their disease. The anti-TNF drugs with which there is extensive experience are infliximab and adalimumab. The role of these drugs in simple fistulas has not been studied (Table 4). Absence or loss of response to anti-TNF agents may be addressed by intensifying treatment or switching to another biologic drug. In daily clinical practice, luminal activity and formation of anti-TNF antibodies must be ruled out, and through blood infliximab levels must be evaluated. The latter measure is particularly interesting since its usefulness in deciding on treatment modifications is currently being investigated. Recent studies have indicated that elevated levels of infliximab (>9–10mcg/ml) are related to better management of PCD. If a patient has low levels, it is recommended that the dose of the anti-TNF drug used be intensified.

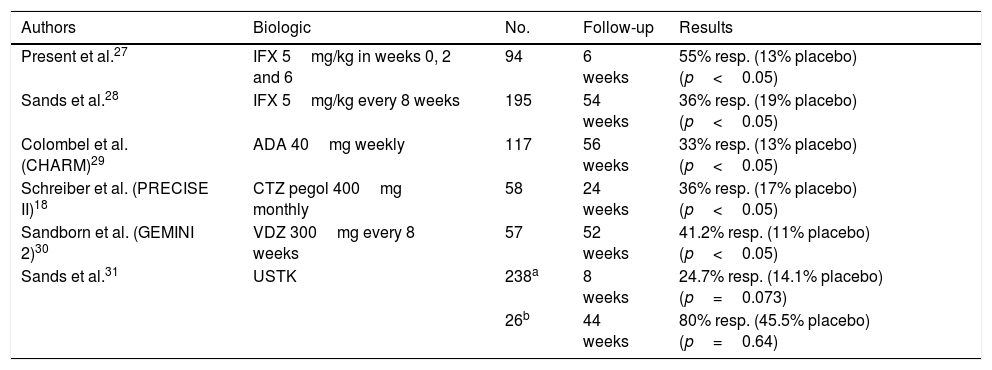

Studies published on the efficacy of biologic drugs in complex fistulas.

| Authors | Biologic | No. | Follow-up | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Present et al.27 | IFX 5mg/kg in weeks 0, 2 and 6 | 94 | 6 weeks | 55% resp. (13% placebo) (p<0.05) |

| Sands et al.28 | IFX 5mg/kg every 8 weeks | 195 | 54 weeks | 36% resp. (19% placebo) (p<0.05) |

| Colombel et al. (CHARM)29 | ADA 40mg weekly | 117 | 56 weeks | 33% resp. (13% placebo) (p<0.05) |

| Schreiber et al. (PRECISE II)18 | CTZ pegol 400mg monthly | 58 | 24 weeks | 36% resp. (17% placebo) (p<0.05) |

| Sandborn et al. (GEMINI 2)30 | VDZ 300mg every 8 weeks | 57 | 52 weeks | 41.2% resp. (11% placebo) (p<0.05) |

| Sands et al.31 | USTK | 238a | 8 weeks | 24.7% resp. (14.1% placebo) (p=0.073) |

| 26b | 44 weeks | 80% resp. (45.5% placebo) (p=0.64) |

ADA: adalimumab; CTZ: certolizumab; IFX: infliximab; resp: response (disappearance of fistula drainage or closure of fistula); USTK: ustekinumab; VDZ: vedolizumab.

If by contrast a patient has low drug levels but with antibodies against the drug, it may be recommended that the patient switch anti-TNF drugs.14 Our results were similar to those reported in the ACCENT II study,15 which was specifically designed to evaluate the results of infliximab in complex PCD, finding that in week 52 fistula closure occurred in 36% of patients treated with infliximab compared to 19% in the group administered placebo. In addition, maintenance treatment with infliximab reduced hospitalisations and need for surgery. The effectiveness of adalimumab was reviewed in a study by Colombel et al. (CHARM).16 Lichtiger et al. designed a study in patients with PCD who did not respond to infliximab and concluded that adalimumab could be an option in these patients (with response in 39% of cases).17

The PRECISE II study evaluated the efficacy of certolizumab pegol in patients with fistulising disease and concluded that this biologic drug could be a therapeutic option in patients with fistulising disease compared to placebo.18 For the moment, no studies favour choosing one anti-TNF drug over another. In a meta-analysis by De Groof et al.,19 of 1449 patients treated with anti-TNF, there were no differences with respect to closure of the fistula opening. However, this was a heterogeneous meta-analysis featuring studies with different levels of evidence and different follow-up periods. It also concluded that combined treatment (an anti-TNF drug with or without an immunomodulator) and surgery show better results than any one of them separately.

Three-quarters of our patients required some sort of surgical technique to manage their PCD. A significant percentage of patients with CD eventually develop perianal abscesses which must be drained. In addition, proctitis temporarily contraindicates fistulectomy, not only due to infectious complications but also because the procedure has been seen to increase the risk of faecal incontinence.4 Surgical drainage has been reported to result in a decreased risk of infectious complications compared to spontaneous drainage.20 Surgical techniques in PCD associated with CD seek to preserve the function of the perianal area with minimally invasive approaches. The essential treatment of simple fistulas is surgery involving placement of a seton and, in select cases, fistulotomy.

In complex fistulas, medical treatment combined with placement of setons is usually the most suitable option.19 The question of when to remove a seton has been extensively debated. Usually, a decision is made on a case-by-case basis in follow-up in surgery visits.15 Most of our patients had a seton in place for more than a year, which enabled suitable management of PCD. Patients who are refractory to the above measures sometimes undergo ileostomies or derivative colostomies. This was true of some of our patients. However, this measure is best avoided and used as a last resort.

The development of new biologic drugs which have a different therapeutic target, and which are already being used in patients with IBD, represents a possible treatment option in refractory cases.

Vedolizumab is a monoclonal antibody that binds to intestinal α4β7 integrin, thereby inhibiting leucocyte adhesion and migration at that level. Studies on this new drug had the primary objective of evaluating luminal response. However, many of the patients enrolled had a fistulising phenotype; therefore, preliminarily, a positive response of this drug for PCD has been seen.21 In our sample, 2 patients started treatment with vedolizumab due to PCD refractory to the biologic drugs approved to date. One of them had a clinical response, and the other ended up undergoing unloading colostomy due to a poor clinical course. Ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody very recently approved for CD, inhibits the activity of human cytokines IL-12 and IL-23 by interfering with the binding of these cytokines to their receptor protein IL-12Rβ1, which is expressed on the surface of immune cells. The preliminary results of the UNITI 1, UNITI 2, CERTIFI and IM-UNITI studies22 (also designed to evaluate effectiveness in luminal disease) indicated that ustekinumab could be a therapeutic alternative in PCD. In a Spanish series,23 61% of patients who received ustekinumab experienced clinical improvement. Further studies with the primary objective of evaluating PCD will elucidate the usefulness of these new treatments in patients with CD and complex PCD.

Despite all the new drugs developed in recent years, complete closure of the fistula is not achieved in a significant percentage of patients (close to 50%). Some of them end up undergoing surgeries with bowel resections which generate significant morbidity. As of late, studies with local injection of mesenchymal stem cells into the fistula tract are under way. These non-hematopoietic multipotent cells are capable of differentiating into different cell types and possess anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating properties; therefore, it seems that they could play a role in PCD.24

Recurrence of PCD occurs in a significant percentage of patients with recurrence of pain and drainage through the fistula opening. In recent years there has been support for a confirmatory imaging test (preferably pMRI due to its specificity) to aid in deciding on the continuity of clinically effective treatments such as anti-TNF drugs.

In cases in which recurrence is confirmed through signs and symptoms (or, ideally, imaging tests), the patient's current and prior treatments should be analysed. The most widely accepted options for the moment are a switch in biologics and surgery.4 Recurrence of PCD involves factors such as fistula type (complex fistulas recur more often and therefore require optimisation of treatment, by means of either a switch in biologic drugs or surgery25). This has also occurred in the series of patients at our centre: those with complex fistulas had significantly more recurrences and a significantly greater need for surgical procedures.

Our study has limitations inherent to its nature. It is a retrospective study with a limited number of cases. In addition, outcomes were measured in terms of clinical response according to findings on physical examination of tracts, and were confirmed with an imaging test in only a fraction of cases. At our centre, we have been able to determine trough anti-TNF levels and anti-TNF antibodies as of only recently. Therefore, this study features no data in this regard, as we were unable to make these determinations when the patients involved were treated. However, we believe that the study offers information on clinical practice in the complex scenario of PCD associated with CD.

ConclusionsPCD should be managed using a multidisciplinary approach (including gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons and radiologists) and combined medical treatment (antibiotics, immunomodulators and biologic drugs plus surgical techniques). The use of antibiotics improves perianal symptoms but does not achieve fistula closure. In our experience, many patients with complex PCD require biologic drugs to manage the condition. These patients had PCD which recurred more often and required more surgeries. Despite recurrences, the effectiveness of biologic drugs is good in this patient type, and these drugs represent first-line treatment in complex PCD. A certain percentage of patients have PCD refractory to current treatments.

Further studies are needed to aid in determining the efficacy and positioning of new biologic drugs and treatments such as local stem cell therapy in PCD associated with CD which could be useful in improving these patients’ quality of life.

Conflicts of interestAlicia Algaba received research funding from MSD. Fernando Bermejo has acted as a speaker and consultant for MSD, Abbvie, Pfizer, Takeda and Janssen. Cristina Rubín de Célix, Iván Guerra, Ángel Serrano, Estíbaliz Pérez-Viejo and Carolina Aulló did not declare any conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rubín de Célix Vargas C, Algaba A, Guerra I, Serrano Á, Pérez-Viejo E, Aulló C, et al. Recursos empleados en el tratamiento de la enfermedad de Crohn perianal y sus resultados en una serie de vida real. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:353–361.