Ipilimumab (Yervoy@) is a humanized IgG monoclonal antibody that specifically blocks the inhibitory signal of cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4) which results in T cell activation, proliferation and lymphocyte infiltration into tumors, leading to tumor cell death. Since its approval, by the Food and Drug Administration (2011), ipilimumab became a new tool for the treatment of metastatic melanoma leading to an improvement in survival rates worldwide.1,2 Thereafter, new types of toxicities have been described with ipilimumab (and related agents), the so called “immune-related adverse events” (irAEs). The most frequent irAEs affect the skin and gastrointestinal tract, in up to two-thirds of the patients.3–5 In November 2013, the European Commission has approved it use as a first-line agent for the treatment of advanced melanoma. Due to the widespread use of this agent, clinicians should be aware and familiarized with the adverse events related to ipilimumab.

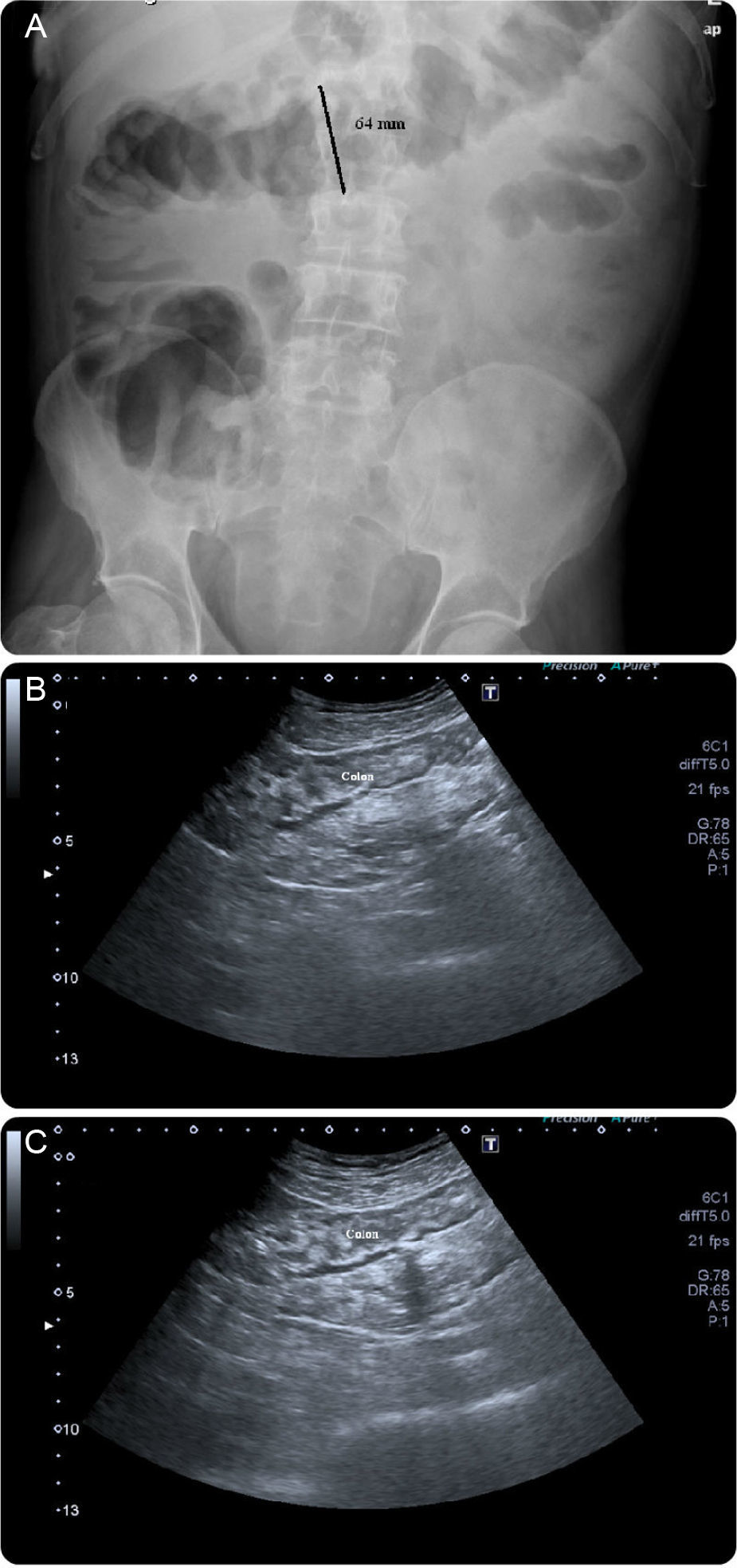

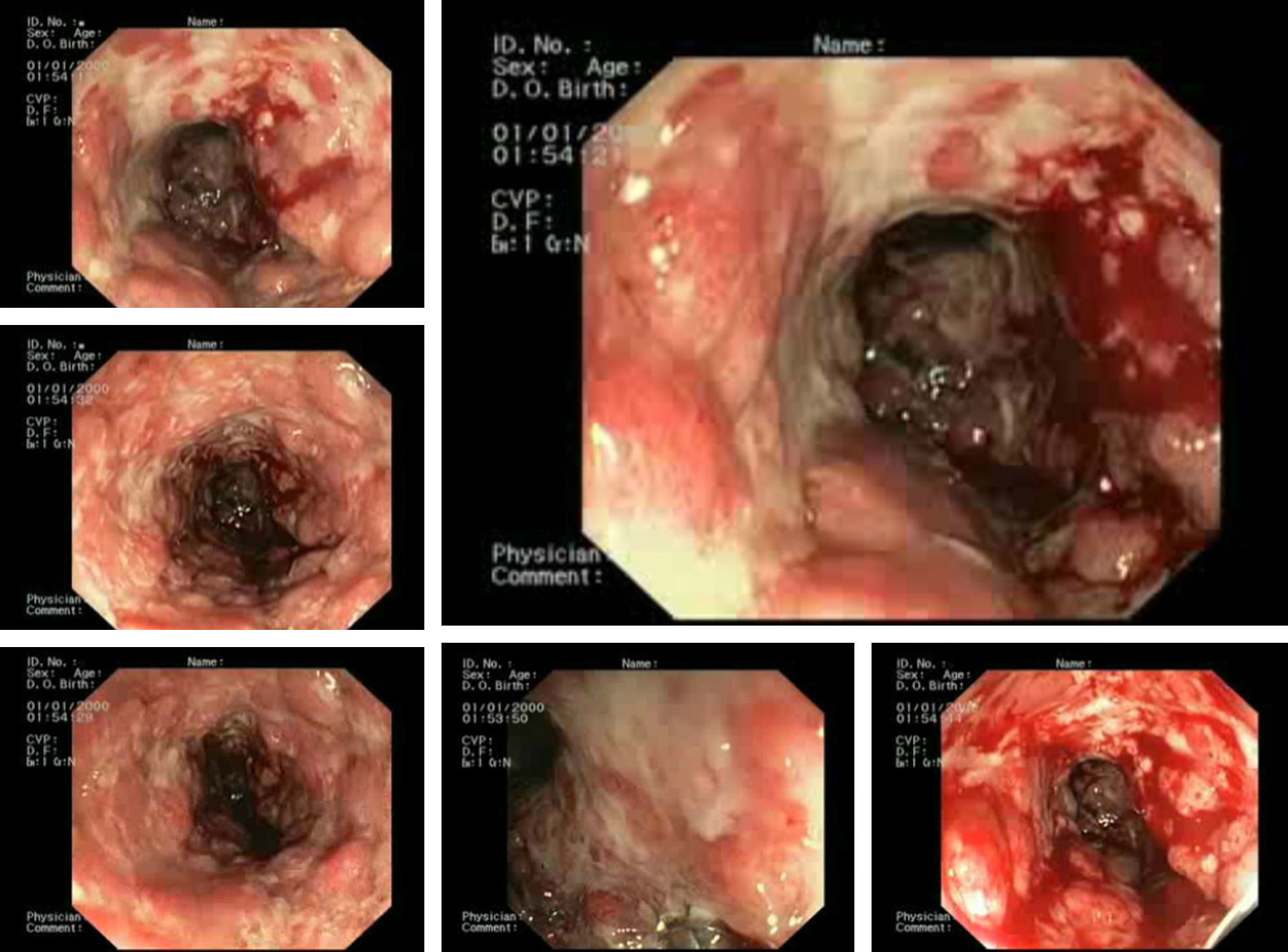

A case of a 62-year-old man with a retroauricular melanoma is reported, in whom it was decided to initiate ipilimumab as second-line chemotherapy (after tumor progression with conventional first-line chemoradiation therapy). Twenty-four hours after first infusion, the patient reported a diffuse abdominal pain and a mild bloody diarrhea (3–4 bloody stools/day). Two days after a second scheduled administration, fever (38–39°C) and vomiting were added to the previous symptoms. At this point, it was decided to withdraw ipilimumab and the patient was given loperamide and reinforced oral hydration. Despite these measures, the patient remained symptomatic leading to an admission in our ward. At presentation he was febrile (38.9°C), hemodynamically stable, moderately dehydrated and in the abdominal examination he had a localized tenderness in the left iliac fossa. The laboratory results showed no anemia ([Hb]=14g/dL), no leukocytosis but a markedly elevated C-reactive protein (20mg/dL; reference value:<0.5mg/dL). Standard stool examinations for bacteria, Clostridium difficile (toxin), ova, cysts and parasites were negative. On using plain abdominal radiograph and abdominal ultrasound (US) no sign of perforation or collection was noticed. Following a discussion with his assistant oncologist it was decided to start intravenous steroids (prednisolone 40mg/day). After seven days of treatment the symptoms improved significantly and the patient was discharged with 20mg of prednisolone/day per os. Seventy-two hours after discharge, the patient returned to our clinic complaining about an increase in the bloody stool frequency (7–10 per day). At that time, he was hypotensive, normocardic and afebrile. Remaining physical examination was unremarkable. It was decided to reinstitute prednisolone at a dose of 40mg/day, intravenously. Despite those measures, symptoms were refractory and the bloody diarrhea did not resolve so fast has it was expected to. On the seventh day of treatment, the patient had a massive hematochezia, with [Hb] drop (to 9g/dL) and C-reactive protein rouse (30mg/dL). Plain abdominal radiographs (Fig. 1A) showed a dilated transverse colon (with a diameter of 64mm) consistent with a megacolon by radiological criteria. Abdominal US showed no intra-abdominal complications, revealing only a slight thickening of the sigmoid wall (5–6mm; Fig. 1B and C). A left colonoscopy was performed (Fig. 2), demonstrating a patchy but extensive and deep ulceration of the left colon, from the splenic flexure until the sigmoid colon, sparing the rectum. The ulcers were covered with exudates and fresh blood. Histological findings were non-specific, demonstrating a mixed inflammatory component (with a lymphoplasmocytic infiltrate of B and T cells), lymphoid aggregates and eosinophils, extensive ulceration and granulation tissue. On the base of the ulcerated tissue, aspects of fibrinoid necrosis of the vessels wall and fibrin clots were visible. Immunohistochemistry excluded the presence of cytomegalovirus inclusions. Broad spectrum antibiotics were promptly initiated and steroid therapy was optimized to 100mg/day intravenously (prednisolone 1.5mg/Kg/day). After 5 days, there was a significant clinical improvement, the patient had less than 3 bowel movements/day (without blood), no abdominal pain and was afebrile. Laboratory tests revealed a marked decrease in C-reactive protein (3.7mg/dL), no leukocytosis and a stable [Hb] (10.8g/dL). After ten additional days, the patient was discharged, medicated with 100mg/day of prednisolone per os followed by a slow weaning course (lasting 8 weeks). Ipilimumab was permanently withdrawn and the patient remains asymptomatic after steroid stoppage.

As ipilimumab administration has shown a survival benefit in metastatic melanoma,1,2 more patients are likely to receive this therapy, and therefore, it is expected that ipilimumab induced gastrointestinal irAEs will be encountered more often. In such scenarios (severe hemorrhagic diarrhea), the performance of a lower endoscopy is recommended6 to confirm or rule out other possible etiologies (e.g., opportunistic infections); however, one must bear in mind that the risk of perforation has been reported to be as high as 20%.1 Our case underlines some important clinical aspects and therapeutic quandaries when facing these situations, first, the importance of offending drug withdrawal and second, optimal steroid dose administration as recommended by the manufacturer, as well as a slow steroid tapering in order to avoid an early and, sometimes, steroid-refractory recurrence.7,8 In cases of steroid-refractory colitis, infliximab therapy (5mg/kg, usually a single dose), as a second-line treatment, should be considered.9,10

Financial supportNone.

Ethical approvalInformed consent was obtained from the patient.