The formation of visceral artery pseudoaneurysms (VAPAs) as a vascular complication of pancreatitis is a very rare phenomenon. Even more exceptional is the formation of localised pseudoaneurysms in the superior mesenteric artery (SMA).

We report the case of a 58-year-old female patient with a history of chronic alcoholism, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, alcoholic liver cirrhosis, and chronic alcoholic pancreatitis with a 32×43mm pancreatic pseudocyst, according to the last CT scan performed in May 2011. No surgical history.

The patient came to the emergency department due to 6h of intense epigastric pain, which irradiated to both hypochondria and was accompanied by nausea and vomiting. No fever or accompanying symptoms were reported. An analysis was carried out showing hyperamylasaemia of 2215U/l, AST/ALT 32/18U/l, total bilirubin 2.7mg/dl, leukocytes 21,910mm3 (91%N, 4%L), Hb 15.1g/dl, Hct 42.9% and INR 1.32. Initially, it was considered an exacerbation of chronic pancreatitis, and it was decided to admit her to the gastrointestinal department to start treatment and monitoring.

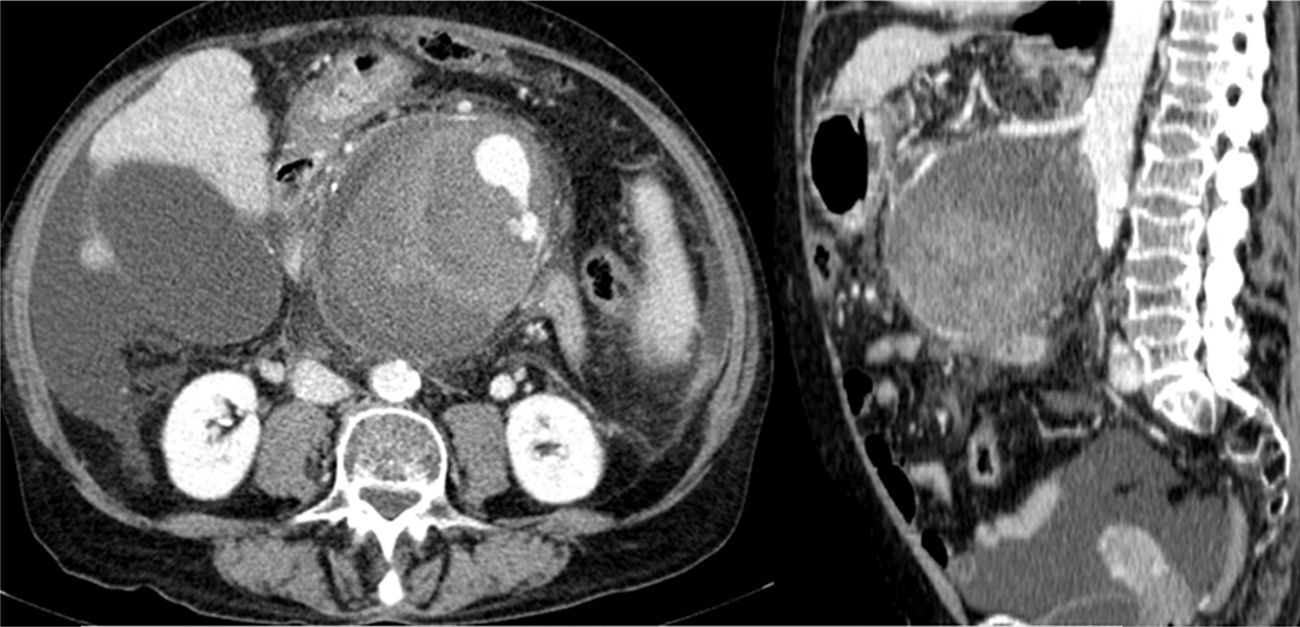

At 24h after arrival, the patient remained haemodynamically stable, although the intense abdominal pain persisted. In the follow-up analysis, acute anaemisation was observed with Hb 10.7g/dl and Hct 29.9%. A CTA was performed which showed signs of chronic pancreatitis, chronic liver disease, diffuse ascites (perihepatic, perisplenic, between bowel loops and in the pelvis) and a heterogeneous collection of blood in various stages of evolution with signs of recent bleeding encompassing SMA, which suggests a contained rupture of a pseudoaneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery (PSMA) (Fig. 1).

The case was consulted with the vascular surgery department, and it was decided to perform an arteriogram with intention to treat with endovascular treatment (EVT) to exclude the PSMA.

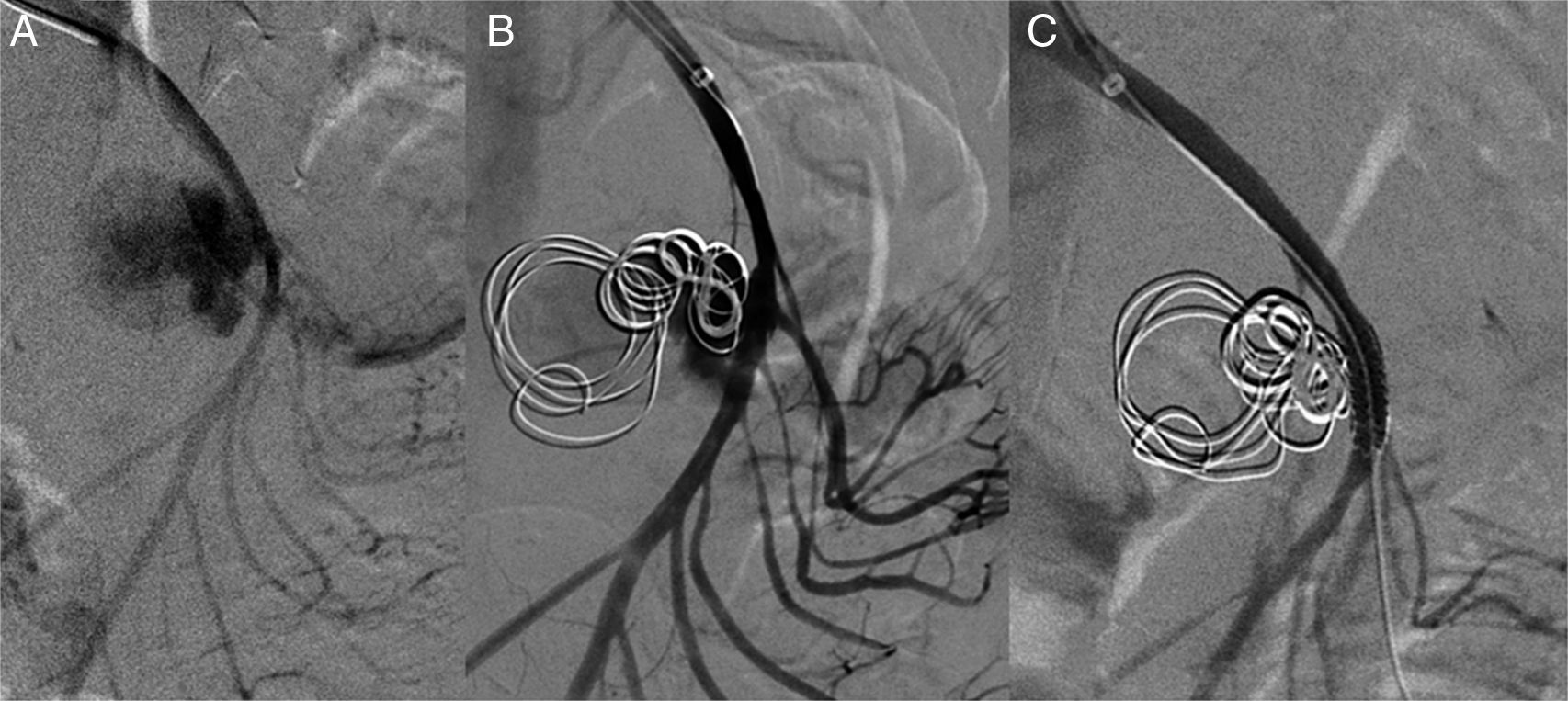

Via a left humeral access, the SMA was catheterised using a multipurpose catheter (COOK®), and a 6F introducer was placed in the origin of the SMA. A selective arteriogram was performed, showing a large wide-neck pseudoaneurysm with an irregular true lumen of approximately 25mm. Using a telescoping technique, the aneurysm sac was catheterised with a Progreat® (Terumo) microcatheter, which was inserted into the pseudoaneurysm. To prevent the coils from migrating to the SMA, a scaffolding technique was used on the sac, initially embolising it with two controlled-release 25×25mm and 20×50mm type DCS (COOK®) J microcoils creating a “cage” and then filling the ball-shaped sac with 15×8mm and 10×8mm DCS spiral microcoils. A control angiograph was performed, showing a contrast image remaining at the entrance to the aneurysm sac. It was assessed whether to continue with this technique, although due to the high risk of arterial lumen invasion by a coil, it was decided to leave the Progreat® microcatheter inside the pseudoaneurysm sac and place a coated 5×28mm stent (BeGraft®) in the SMA. Then it was embolised with a new 10×8mm DCS spiral coil to finish excluding the pseudoaneurysm.

In verifying the arteriogram, complete exclusion of the aneurysmal sac with SMA permeability was observed and with preserved collaterality except in the area where the stent was placed where there is no contrast of various jejunal branches (Fig. 2).

During her hospital stay, the patient had no complications related to vascular disease, and did not develop anaemia again. She was discharged 20 days after the EVT.

She was later monitored in outpatient consultations via CTA at one and three months after the intervention. No growth or effusions were observed in the aneurysm cavity, the stent remained permeable and there was no stenosis. The patient remained clinically asymptomatic.

In light of the previous case, we can highlight that the incidence of pseudoaneurysms as a complication after pancreatitis is low and not well established. Some reported case series establish a range of incidence of 1.2–14%,1 with an incidence of 1–6% in acute pancreatitis and a higher incidence of 7–10% in chronic pancreatitis due to its frequent association with pancreatic pseudocysts.2

Different mechanisms have been suggested to explain the formation of pseudoaneurysms. The two most accepted theories are related to: the presence of a pseudocyst that erodes and weakens the wall of an artery adjacent to the pancreas, leading to the formation of a pseudoaneurysm, and the activation of proteolytic enzymes within pancreatic tissue, which causes auto-digestion of pancreatic tissue and of the adjacent structures.3,4

The arteries most affected by proximity to the pancreas are the splenic artery (50%), followed by the gastroduodenal artery (20–50%) and the pancreatic-duodenal arteries (20–30%). The rest of the visceral arteries tend to be affected in 10% of cases.1,5

Some of the factors that increase the risk of vascular complications include necrotising pancreatitis, multiple organ failure, sepsis, abscesses, pseudocysts or pancreatic necrosis and anticoagulant therapy.2,6

Unlike true aneurysms, the majority of VAPAs are symptomatic. Abdominal pain is common and, in the case of rupture, different types of bleeding include: hemosuccus pancreaticus, gastrointestinal haemorrhage into the retroperitoneum and abdominal cavity, among others.6 Regarding the diagnosis and study of VAPAs, CTA is the first-choice test, although the gold standard in these cases would be an arteriogram, which allows for endovascular treatment at the same time.7,8

VAPAs always require treatment, independent of their size and the symptoms. Conservative treatment is not recommended due to the high rate of rupture and a mortality of up to 90% in untreated cases. The main objective of treatment is exclusion of the aneurysm sac.9 Classic treatment includes reconstructive surgery or ligation, but due to its high morbidity and mortality (50–100%) it has been replaced in most cases by endovascular treatment, since it is related to a low risk of complications and lower mortality (13–50%).3

The objective of EVT is exclusion of the aneurysm sac via embolisation and/or placement of a stent in the affected artery.9 The global technical success is high: 79–100%. However, in 6–55% of cases, more than one procedure is necessary to achieve full exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm.3

Please cite this article as: Pantoja Peralta C, Moreno Gutiérrez Á, Gómez Moya B. Pseudoaneurisma de arteria mesentérica superior por pancreatitis crónica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;40:532–534.

![Abdominal CTA: showing the PSMA (102×98×103mm [AP×LL×CC]). Abdominal CTA: showing the PSMA (102×98×103mm [AP×LL×CC]).](https://static.elsevier.es/multimedia/24443824/0000004000000008/v1_201710010015/S2444382417301347/v1_201710010015/en/main.assets/thumbnail/gr1.jpeg?xkr=ue/ImdikoIMrsJoerZ+w96p5LBcBpyJTqfwgorxm+Ow=)