Globally, the incidence of pancreatic adenocarcinoma is rising, making it the most likely diagnosis in a patient with radiological suspicion of a pancreatic tumour. However, there are other neoplasms that, although less common, from a radiological viewpoint lead us to suspect a pancreatic cancer, such as autoimmune pancreatitis, certain neuroendocrine tumours (NET) or even pancreatic metastases of other origins. Correct diagnosis of neoplasms of this type is crucial when considering the optimal therapeutic strategy.

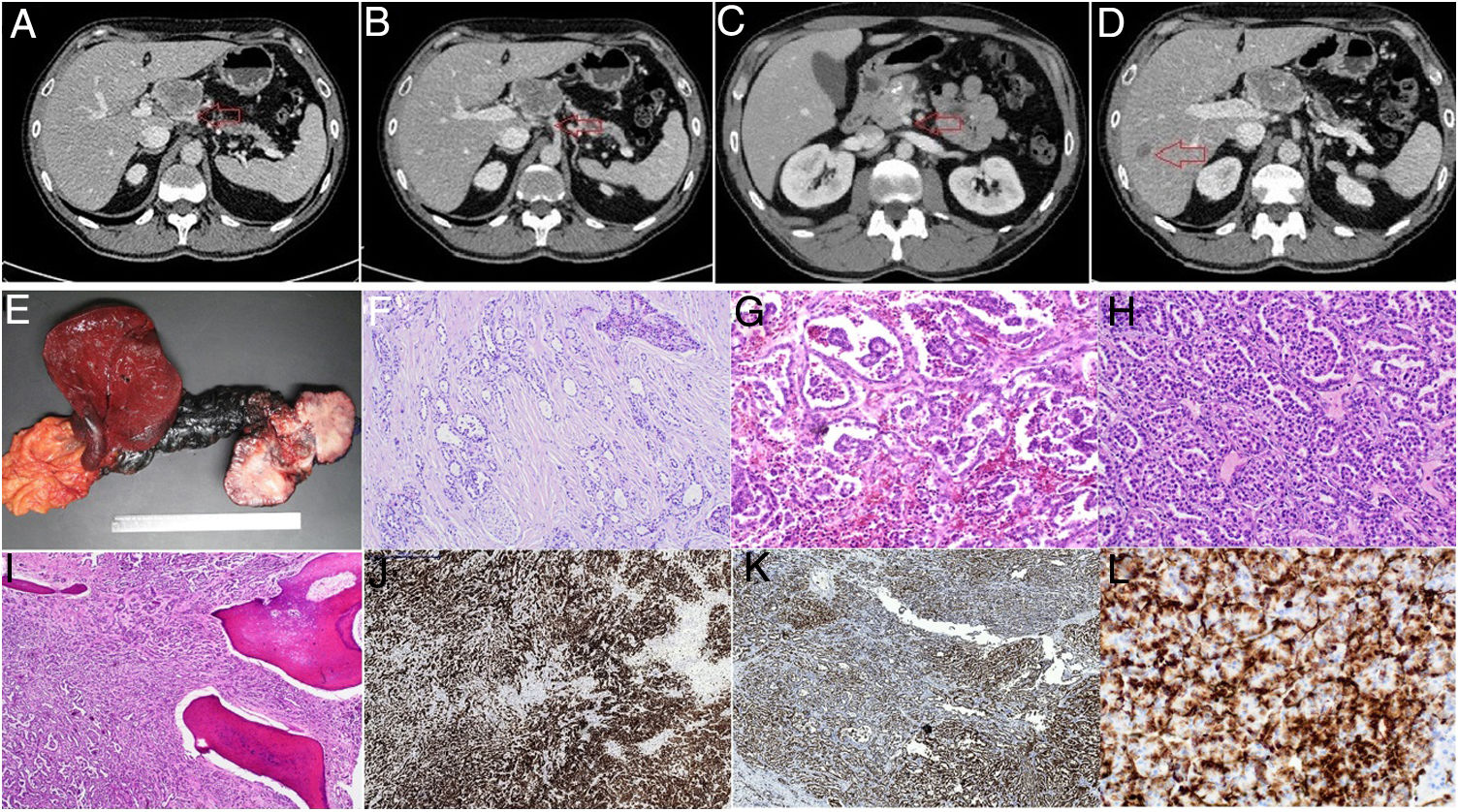

We present the case of a 58-year-old male, incidentally diagnosed by computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 1) with a solid lesion in the neck of the pancreas with distal atrophy and duct of Wirsung dilation (7 mm), in intimate contact with the hepatic artery, splenic artery (<180°) and coeliac trunk; he also presented >50% contact with the superior mesenteric vein and <50% contact with the portal vein, without arterial involvement. Further radiological alterations were observed that could correspond to liver metastases in segments VI and VII.

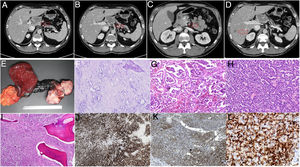

Images from the preoperative CT and the anatomical pathology study: A: contact with the hepatic artery. B: contact with the coeliac trunk. C: contact with the superior mesenteric vein. D: metastasis in segment VI. E: surgical specimen: extended corporeo-caudal pancreatectomy and liver resection. F: haematoxylin-eosin (HE) stain, infiltrative growth with perineural invasion. G: HE stain, pseudoglomerular formations. H: HE stain, tubular growth pattern. I: HE stain, osseous metaplasia. J: CK19. K: inhibin. L: vimentin.

A study of the tumour was initiated and tumour markers sought, with negative results for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and positive results for carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 (46.53 U/ml).1

An endoscopic ultrasound was ordered, with findings consistent with the CT.

A cytology sample taken by endoscopic ultrasonography-guided transgastric biopsy completed the study; on analysis, it was reported to be pancreatic parenchyma consisting of a proliferation with a morphological pattern suggestive of a neuroendocrine tumour.

The immunohistochemical study showed intense expression of antibodies for cytokeratins AE1/AE3 and for CD56, although cytokeratin 7, chromogranin and synaptophysin were not detected. The Ki-67 index was 5%.

The lesion’s appearance, suggestive of NET, and CD56 expression oriented the diagnosis toward neuroendocrine carcinoma, probably with low tumour cell secretion and, therefore, negativity for the antibodies mentioned above.

In view of these findings, an octreotide scan was ordered, which showed no pathological accumulations other than the known pancreatic mass, without significant uptake of the tracer.

With the results obtained in the preoperative tests and a presumptive diagnosis of NET, and given that the level of suspicion of liver metastasis was low and that the only curative treatment for these tumours, when localised, is surgery,4 taking into account the World Health Organisation (WHO) 2017 NET classification,5 the decision was made to treat surgically.

The patient underwent intraoperative biopsies of the suspicious liver lesions (with findings of focal steatosis) and extended corporeo-caudal pancreatectomy with resection of the superior mesenteric vein.

Following an exhaustive anatomical pathology study of the surgical specimen, which included pathologists from several national and international centres, it was reported to be a 7.4 cm tumour located in the body of the pancreas, with a macroscopic appearance of a polilobulated solid mass with a central calcification (Fig. 1).

Microscopically, it presented expansive growth with loose stroma and extensive areas of osseous metaplasia, forming cords, tubules, pseudopapilas and glomeruloid structures. Areas with clear cells and signet ring cells were observed. The tumour was composed of medium-sized cells with ample eosinophilic cytoplasm, with an oval nucleus and not particularly prominent nucleolus with the presence of nuclear clefts, with slight atypia. Occasional signs of mitosis and apoptosis were observed.

Extensive angiolymphatic, venous and perineural invasions and infiltration in the peripancreatic fat were observed, as well as infiltration in the superior mesenteric vein. Metastases were found in two of 25 lymph nodes (the largest of 1 cm) with capsule rupture and invasion of the perinodular soft tissues.

The proliferation index estimated using Ki-67 was 10%.

The immunohistochemical study revealed positivity for cytokeratin 8/18 and 19, CD56, E-cadherin, MUC-1 and inhibin alpha. Focal expression of CD10, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) and vimentin, and cytoplasmic expression of beta-catenin were also found.

Immunohistochemical stains were negative for synaptophysin, chromogranin, cytokeratin 7, racemase, TTF-1, napsin A, cytokeratin 20, CDX2, calretinin, WT-1, CD30, HMF-1beta, alpha-foetoprotein, OCT3/4, GATA3, S-100, Melan A, oestrogen receptor, progesterone and androgen receptors, Glypican 3, MUC5, CD99, HMBE-1, ERG, D2-40, PAX8, PLAP and hepatocyte antigen.

The molecular study of the mutation of exon 3 of the beta-catenin gene and the next-generation sequencing (NGS) study were both negative. No significant changes were identified in the regions analysed (KRAS exons 2, 3 and 4, NRAS exons 2, 3 and 4, BRAF exon 15, GFR exons 18, 19, 20 and 21 and PIK3CA exons 10 and 21).

Following the full study and in view of the histological appearance and immunohistochemical profile, the first diagnostic option given was a metastasis of a renal or testicular carcinoma; the other diagnostic option towards which we lent was an unclassifiable primary pancreatic tumour with aberrant morphological, molecular and immunohistochemical features. The patient’s preoperative images were reviewed, finding no renal or testicular lesions, and a positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan was performed with no evidence of pathological contrast uptake. Physical examination of the patient was always unremarkable, and he presented no symptoms or clinical picture of any kind. No adjuvant treatment was given and after a year and a half of follow-up no recurrence has been identified.

Anatomical pathology analysis plays an essential role in cancer, providing confirmatory diagnosis of the pathology with therapeutic implications, allowing targeted adjuvant treatment to be planned and giving a prognosis.

In this case, the anatomical pathology examination firstly ruled out the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma, neuroendocrine tumour or an inflammatory process of any type. Nevertheless, it was still inconclusive as it offered a diagnosis of either a metastatic tumour from an unidentified primary or an unclassifiable pancreatic tumour, in an asymptomatic patient with a normal physical examination. The histological findings gave a poor prognosis2 with regard to the risk of both local and remote recurrence, with lymph node, vascular and perineural invasion with involvement of the margin and invasion of the large vessels.

These results have a significant impact on the patient's prognosis. For metastatic tumours from an unidentified primary, survival is low (median five to 10 months) and response to treatment is often limited.3 In our case, the patient continues to show no signs of disease at one year of follow-up, now testing negative for tumour markers and with no signs of recurrence in follow-up imaging tests.

For an unclassifiable primary tumour, the choice of adjuvant treatment is difficult and the response may be inadequate.

In spite of our lack of knowledge of the tumour's origin, we believe that its full description may be of interest with regard to the possible identification of a previously unknown and very rare primary neoplasm.

Please cite this article as: Pareja Nieto E, Zhou JY, Rodríguez Blanco M, Sánchez Cabús S, Szafranskay J. Tumor pancreático no clasificable. A propósito de un caso. Gastroenterología y Hepatología. 2021;44:559–561.