Capsule endoscopy is widely accepted as the preferred diagnostic test in the evaluation of small bowel diseases, especially in the setting of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. It has revolutionized small bowel examination and has improved the detection of small bowel tumors. However, small bowel tumors are sometimes missed by capsule endoscopy. Furthermore, there are several recent reports comparing capsule endoscopy with other diagnostic modalities, such as double balloon enteroscopy and CT/RM enterography, that challenge the reportedly high negative predictive value of capsule endoscopy in detecting small bowel tumors.

We report the case of a patient with overt obscure gastrointestinal bleeding due to a gastrointestinal stromal tumor diagnosed by CT enterography after two negatives capsule endoscopies. This case shows that capsule endoscopy may overlook significant life threatening lesions and highlights the importance of using other diagnostic modalities after a negative capsule endoscopy, especially in patients with a high index of suspicion for small bowel tumoral pathology or persistent/recurrent bleeding.

A enteroscopia por cápsula é um dos principais métodos de diagnóstico de lesões do intestino delgado, em especial no contexto da hemorragia digestiva obscura.

A enteroscopia por cápsula revolucionou a avaliação do intestino delgado e a deteção de tumores. No entanto, os tumores do intestino delgado nem sempre são diagnosticados por enteroscopia por cápsula. Vários artigos que comparam a enteroscopia por cápsula com outros métodos de diagnóstico, como a enteroscopia por duplo balão ou a enterografia por tomografia computorizada/ressonância colocam em causa o elevado valor preditivo negativo da cápsula endoscópica na deteção de tumores do intestino delgado.

Os autores descrevem o caso de uma doente com hemorragia digestiva obscura manifesta devido a um GIST diagnosticado por enterografia por TC abdominal após realização de duas enteroscopias por cápsula que foram negativas. Este caso demonstra que a enteroscopia por cápsula pode não diagnosticar lesões com significado clinico e realça a importância de utilizar outros métodos de diagnóstico, especialmente em doentes com elevado índice de suspeição de tumores do intestino delgado ou hemorragia persistente/recorrente.

Capsule endoscopy (CE) became a first-line diagnostic tool in obscure gastrointestinal bleeding (OGIB) and has gained a significant role for small bowel (SB) tumor detection and surveillance in polyposis syndromes, mostly in Peutz-Jeghers syndrome (PJS).1 CE is safe and non-invasive, it enables visualization of the entire small bowel and has been shown to be superior to push enteroscopy, small bowel follow-through and computed tomography in detecting small bowel bleeding lesions.2–4

In OGIB, a negative CE has been associated with a low rebleeding risk, and it has been suggested that further investigation of these patients can be reasonably deferred until rebleeding occurs.5,6 After a negative surveillance CE in PJS, additional investigations must only be performed if persisting clinical symptoms suggest a missed lesion.

Although highly effective, CE has technical limitations, which increase the risk of missing significant pathology: incomplete small-bowel transit, poor luminal-view quality, visualization of only the mucosal surface, inadequate luminal distension and rapid transit through the duodenum and jejunum. There is increasing evidence concluding that small bowel tumors (SBT) may be missed by CE in patients with OGIB and that a negative CE study does not exclude significant disease, suggesting that double-balloon enteroscopy and CT/MR enterography should be considered as alternative diagnostic methods when clinical suspicion persists.7–9

2Clinical caseA 46 year-old woman presented to the emergency department with melena and marked fatigue for 1 week. Two years before, she had a similar clinical episode that was thought to be caused by a duodenal ulcer associated with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection. 10-day sequential treatment was indicated and a subsequent histology was negative for H. pylori. The patient denied abdominal pain, weight loss or changes in bowel habits. She was not taking any medication including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. She was hemodynamically stable and the abdominal examination was normal.

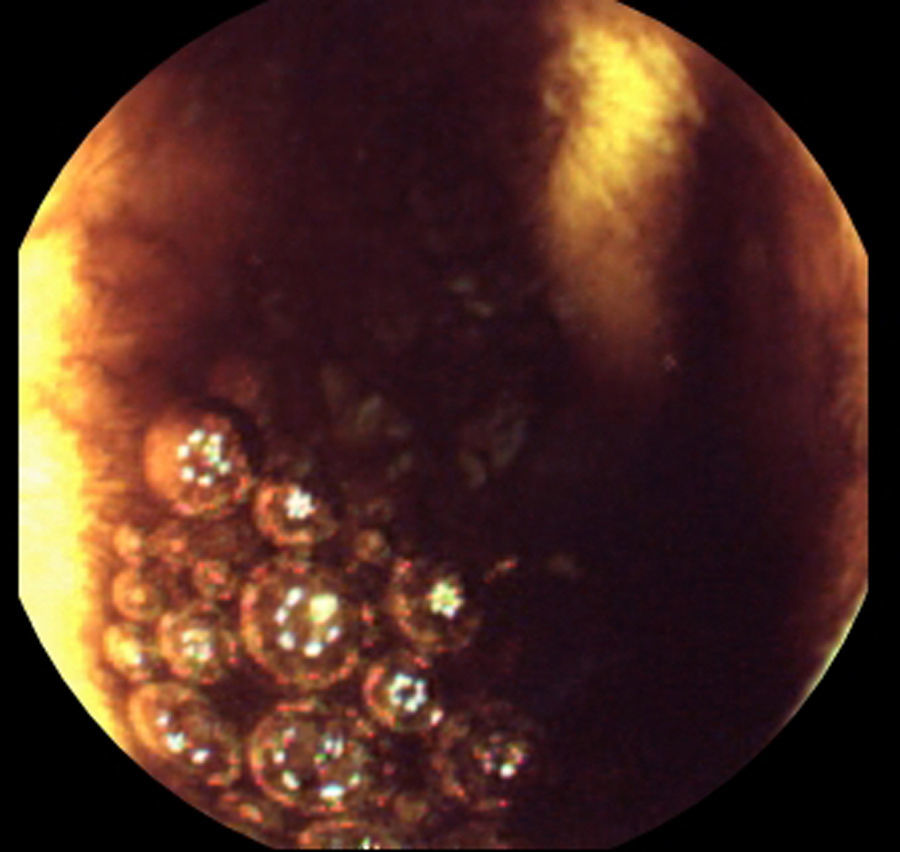

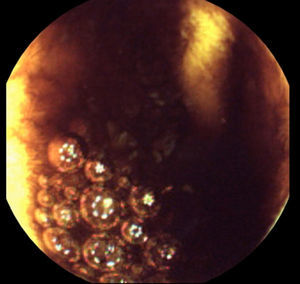

Laboratory data demonstrated a low hemoglobin level (6.8g/dl); white blood count, liver tests and C-reactive protein were in the normal range. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed an 8mm Forrest III duodenal ulcer; there was no blood in the stomach or duodenum. A same day colonoscopy revealed large amounts of blood in the colon that prevented progression beyond the splenic flexure, even after bowel preparation. The next day, ileocolonoscopy revealed very small amounts of blood in the ileum and colon that were easily removed by water and no lesions in the colon nor in the distal 15cm of ileum. Based on these results, a CE (after 12h of fasting and without bowel preparation) was performed 36h later. It revealed no blood or lesions in the entire small bowel, although the observation of the ileum was hampered by some luminal content (Fig. 1). The next day, after transfusion of two units of red blood cells, she had no more gastrointestinal bleeding and the hemoglobin level remained stable (9g/dl).

One month later, a second CE was performed after oral ingestion of 2L of polyethylene glycol. As in the first CE, the observation of the ileum was also hampered by residual luminal content. A careful retrospective review of the two CE by two experienced gastroenterologists showed no lesions in the small bowel.

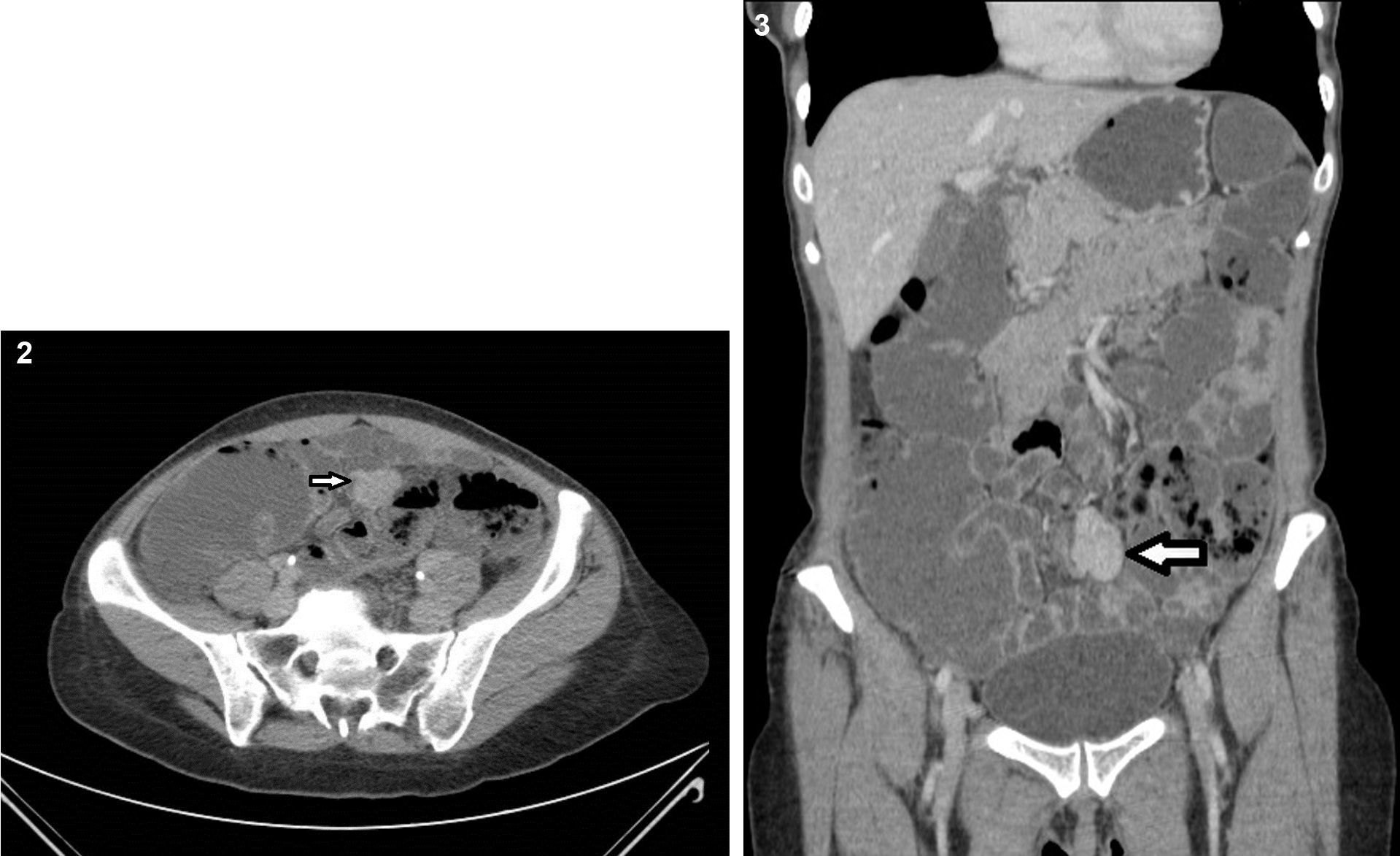

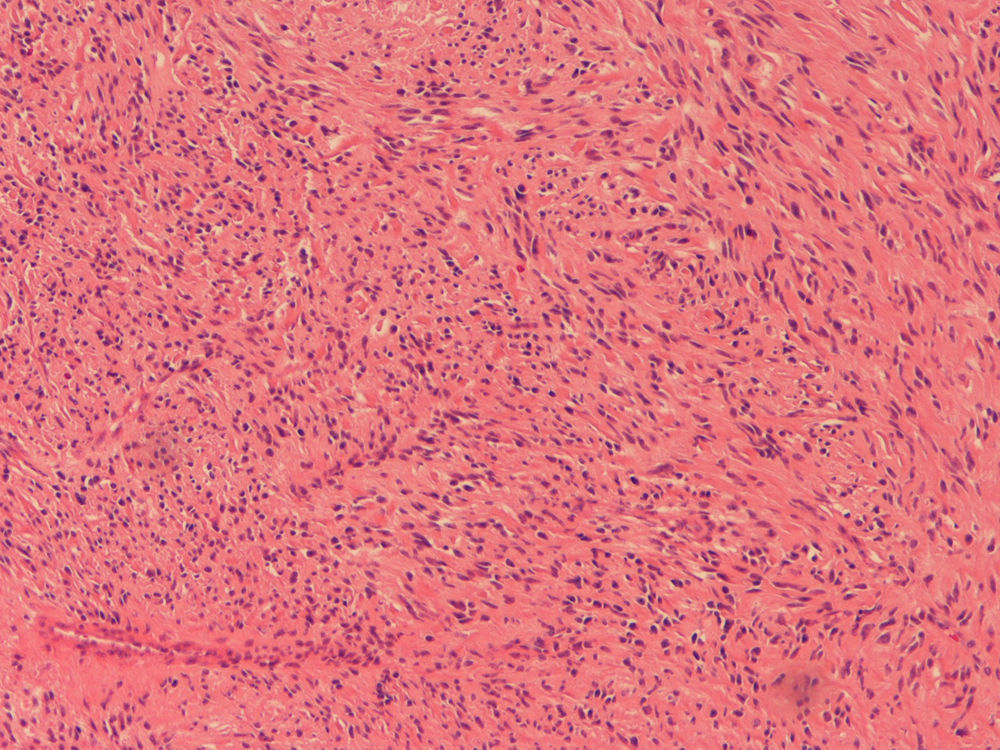

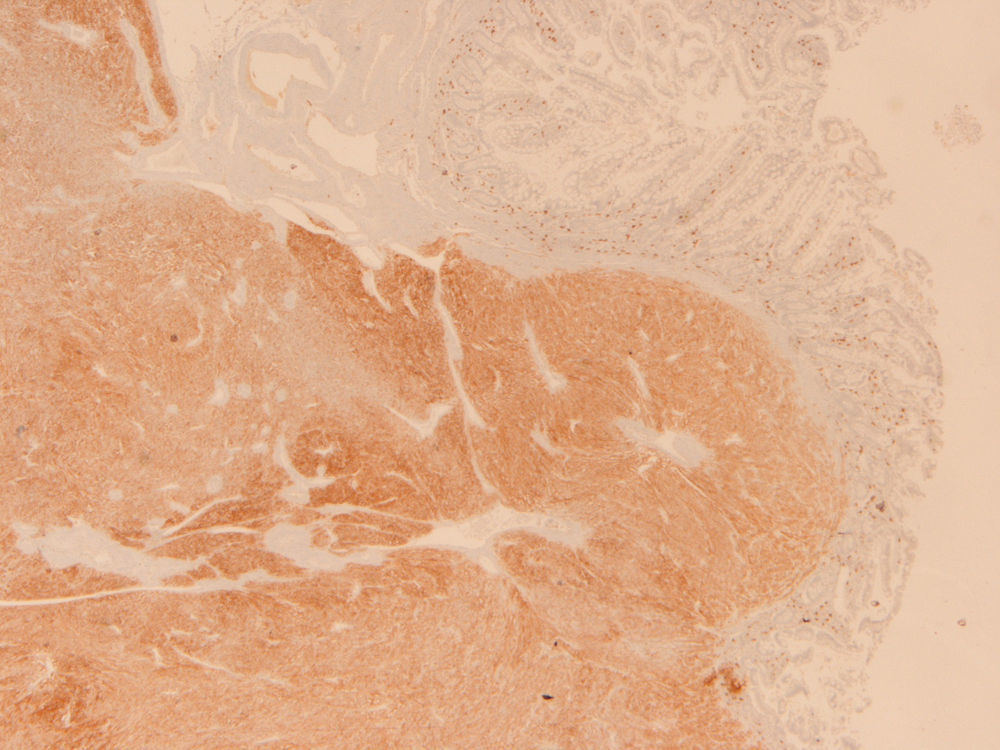

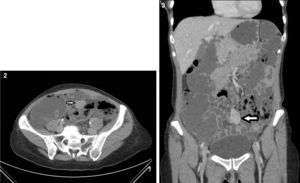

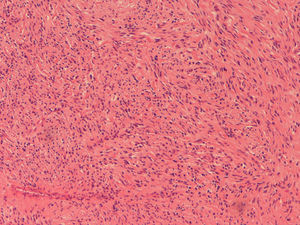

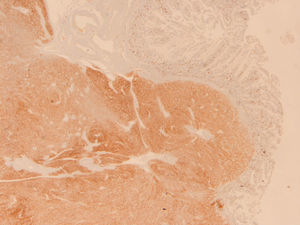

Because the patient maintained iron-deficiency anemia (hemoglobin=10g/dl; serum iron=21ug/dl; ferritin=12.3ng/ml; transferrin=9.1%) despite oral iron therapy, a CT enterography was performed. It revealed a 29mm×39mm mesenteric hypervascular lesion probably located in the mid ileum, with homogeneous contrast enhancement, although its intraluminal or extraluminal location was impossible to define. The first diagnostic hypothesis was a gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) (Figs. 2 and 3). The patient underwent an elective laparoscopy, in which a 3cm extraluminal serosal tumor was resected from the mid ileum; the respective mucosa had a 14mm procidentia without ulceration. Microscopic examination confirmed a low grade GIST (pT2N×G1R0) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Small bowel tumors (SBT) such as carcinoids, GIST and primary and metastatic cancers are responsible for OGIB in up to 10% of cases.10,11 CE is increasingly used to detect small-bowel mass lesions, and has demonstrated improved sensitivity compared with traditional radiologic techniques for SBT detection.12,13 However, several recent reports after the development of new alternative endoscopic/imaging techniques, such as double balloon enteroscopy and CT/MR enterography, have highlighted potential limitations in capsule technology, particularly in the identification of SBT. Postgate et al.1 reported four SBT diagnosed by other modalities after being missed on CE (double balloon enteroscopy in 2 patients, CT enterography and MR enterography in the 2 remaining patients). Lewis et al.,14 in a review of pooled CE data, reported that 10% of SBT were missed by CE and were identified by alternative small bowel imaging techniques. Soares et al.15 found that up to 20% of large polyps were missed by CE in patients with PJS and Zagorowicz et al.9 concluded that neoplasms may be missed by CE, especially in the proximal small bowel, suggesting that in some cases of OGIB, complementary endoscopy and/or radiologic test may be indicated.

There are several reasons why SBT may be missed by CE. CE only visualizes the luminal surface of the small bowel, and unless a tumor causes mucosal disruption, it may go undetected.16 Unlike vascular lesions, that may be present throughout the small bowel, mass lesions are typically unifocal and at the current image capture rate of 2–4 frames per second, focal lesions are more likely to be missed than those that are diffuse. Moreover, abnormalities may not be visualized due to the limitations imposed by the random movement of the capsule during transit and unidirectional views. But even large tumors may be missed on CE as showed by some reports.1,17 Also, the rapid transit time in the proximal small bowel, angulations and folds hiding lesions, incomplete studies to the cecum and poor bowel preparation are many potential reasons why false negative results occur with CE.

Our patient had two episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding, the first attributed to a duodenal ulcer. Two years later, she had a recurrence, and again, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a duodenal ulcer with the same characteristics as in the previous episode. However, taking into account that this was the second bleeding episode not totally explained by a Forrest III duodenal ulcer, a CE was promptly performed, as several studies have proved a higher diagnostic and therapeutic yield when endoscopic small bowel studies are performed closer to the bleeding event.18

A variety of lesions may result in small bowel bleeding, with the etiology being different in various age groups: in elderly patients (>65 years old) vascular lesions (54%) and ulcers are the common causes; in the middle age (41–64 years) vascular anomalies (54.4%) and SBT (31.3%) are the major causes, and in young adults (<40 years) the leading causes are Crohn's disease (34.5%) and SBT.19,20 So, considering that the major cause of OGIB in the age group of our patient is a vascular lesion, a CE was performed. It was ingested in the first 48h of bleeding, it was complete to the cecum and did not reveal any lesions; however, observation of the ileum was hampered by some luminal content.

Management of patients with a previous negative CE is controversial. Few studies have reported on repeat CE in the same patient, so data regarding this diagnostic strategy is limited. Svarta et al.21 conclude that repeat CE appears to be of benefit in patients with a previous incomplete study or poor bowel preparation before subsequent SB studies. The American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy22 recommends to repeat CE or to perform deep enteroscopy in patients with a history of recent overt OGIB who now have no evidence of ongoing bleeding. However, other options like CT enterography should be considered.

Because small bowel visualization was limited by luminal content, a second CE was performed some weeks later, before CT enterography was considered. But even after ingesting 2L of polyethylene glycol the evening before the procedure, there still was some residual luminal small bowel content. Both CE were reviewed by two experienced gastroenterologists that did not identify the lesion. Poor bowel visualization, in addition to the fact that the GIST had a predominantly extraluminal location with only a small mucosal procidentia without ulceration, may have contributed to miss the underlying mass lesion on both CE. Whatever the reason for false negatives, our case demonstrates that CE may overlook significant life threatening lesions and cast doubt on the high negative predictive value of CE.

Less invasive tests may be useful to evaluate OGIB after a negative CE. In our patient, SBT was only detected by CT enterography. Postgate et al.1 also described a patient with a large gastrointestinal stromal tumor only detected by CT enterography. CT enterography or MR enterography can be alternative techniques to identify SB lesions that have a predominantly extraluminal rather than intraluminal component. However, CT enterography has some limitations, especially in patients intolerant to oral contrast, with GI dysmotility and with inadequate bowel distention secondary to bowel obstruction. Furthermore, CT enterography can miss flat lesions like angiodysplasias, dieulafoy's lesions and ulcers, which can be better detected by CE. On the other side, in a recent report, a large jejunal polyp was found on CE in a patient with PJS that was previously missed in CT enterography.23

In most comparative studies, CE has been proved to be superior to CT in the evaluation of OGIB. However, in a recent prospective study comparing CE and multiphase CT enterography in OGIB the authors showed that the sensivity of CT enterography in identifying small bowel bleeding was superior to CE (88% vs 38%, p=0.008).7 The improved sensitivity of CT enterography in this study was mostly due to improved detection of SBT, with CE depicting only three of the nine lesions identified in CT enterography. In another blinded prospective study, CT enterography detected 9/9 (100%) SBT compared with 2/9 (22%) by CE.24 Other investigators have also shown that CE may fail to depict clinically significant small bowel masses, particularly as some SBT such as carcinoids or GIST may not have a mucosal component.1 But even large lesions can be missed. Grupta et al.25 found that CT enterography may be less prone to miss large polyps than CE in patients with PJS and may be more reliable in their assessment.

Although CE has greatly facilitated SB imaging and is considered the gold standard in evaluating patients with SB disease, especially those with OGIB, this case shows that CE may overlook significant life threatening lesions and highlights the importance of using other diagnostic modalities after a negative CE in patients with a high index of suspicion for small bowel tumoral pathology or persistent/recurring bleeding. In younger patients, where SBT are one of the most important causes of OGIB, CT enterography should be considered the first diagnostic test for small bowel evaluation after a negative CE.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.