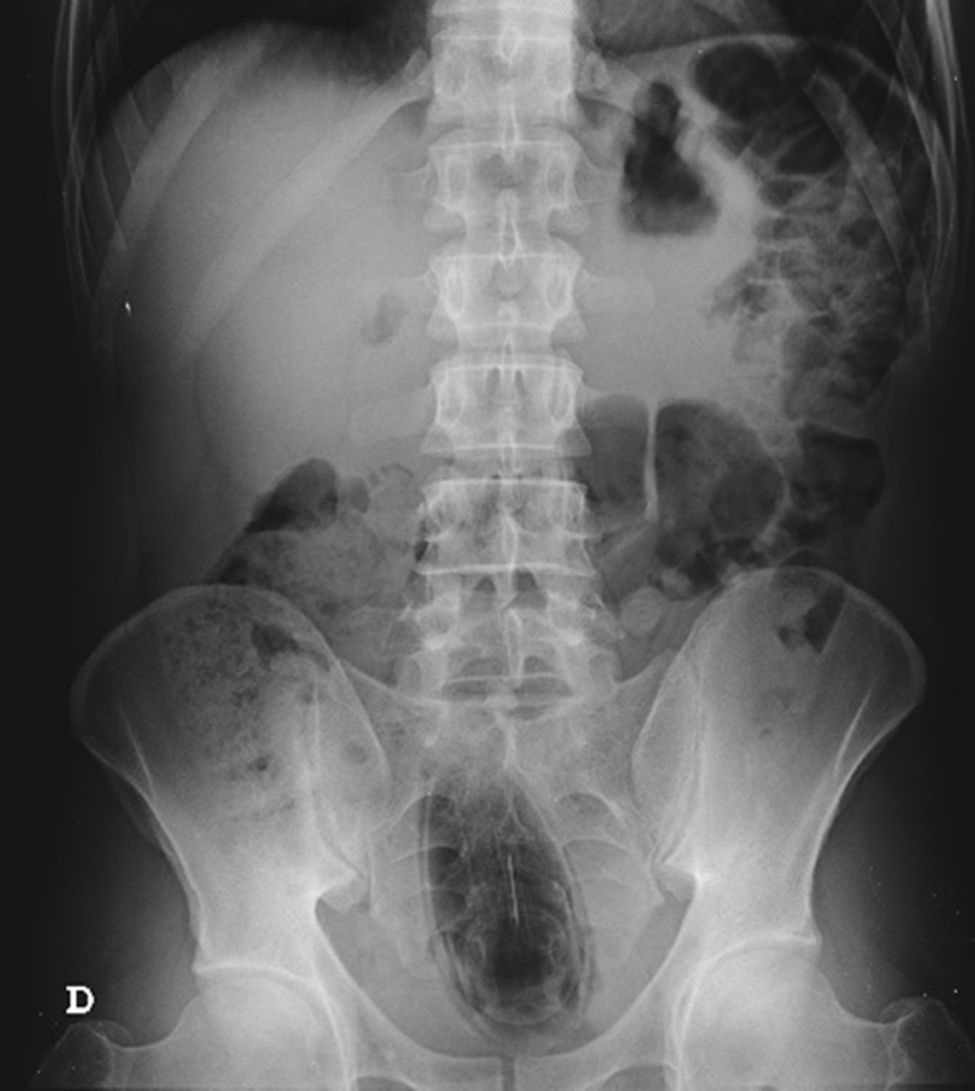

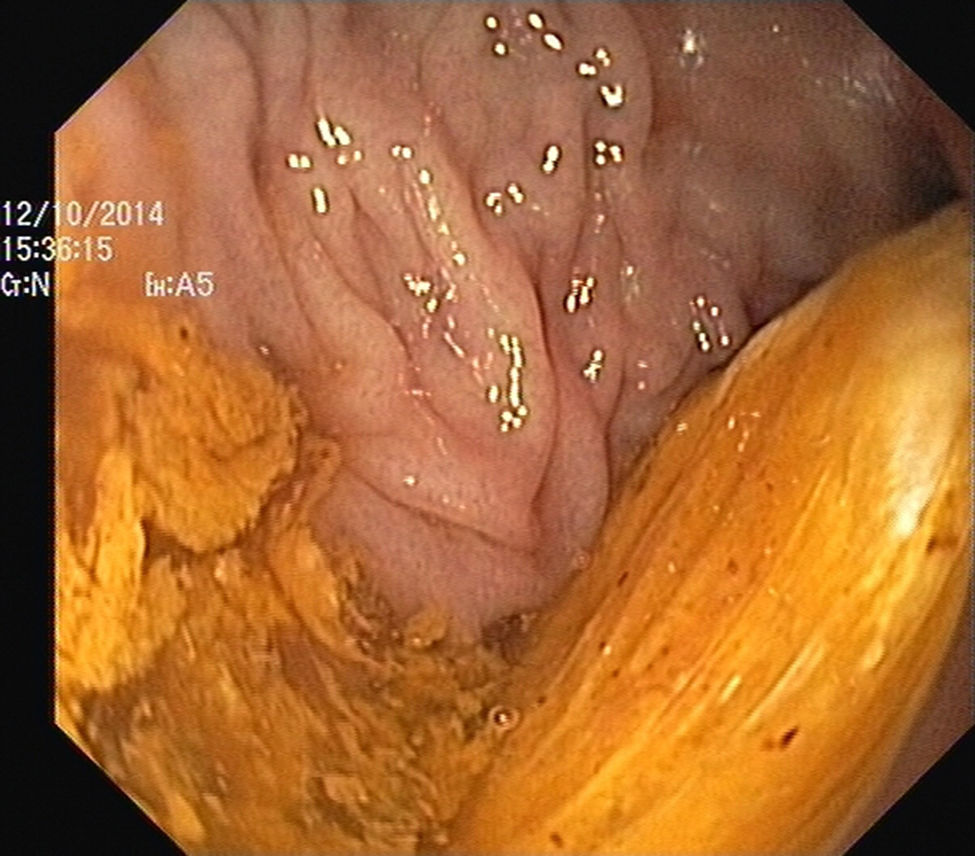

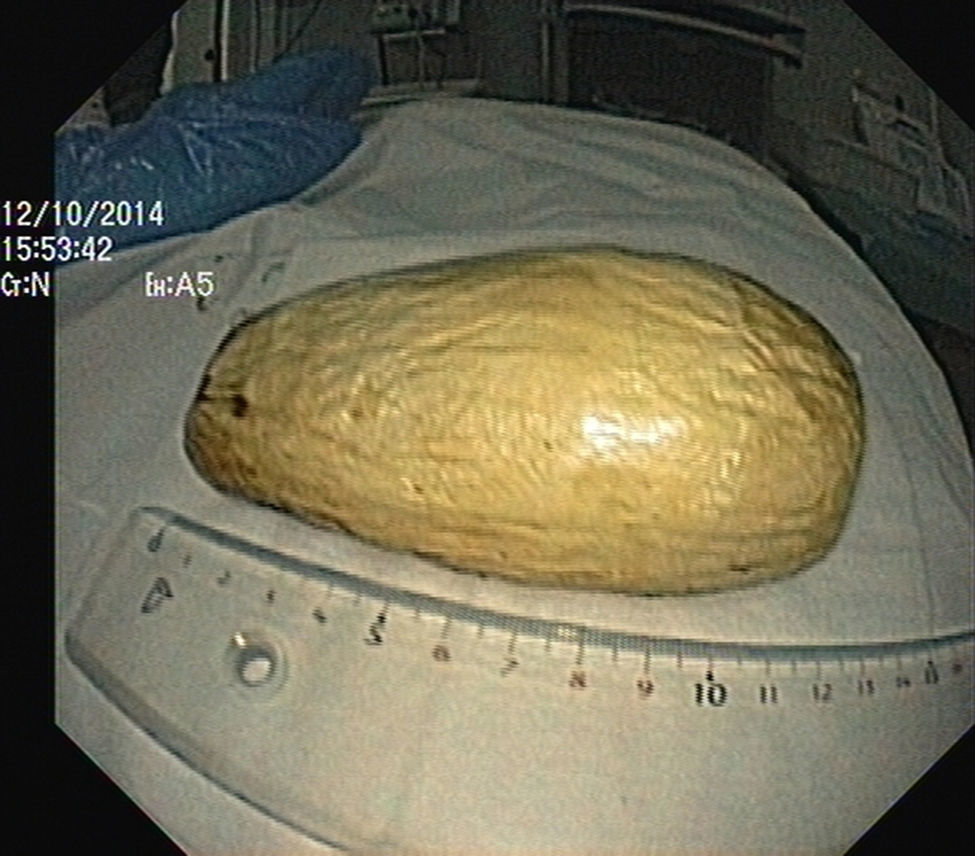

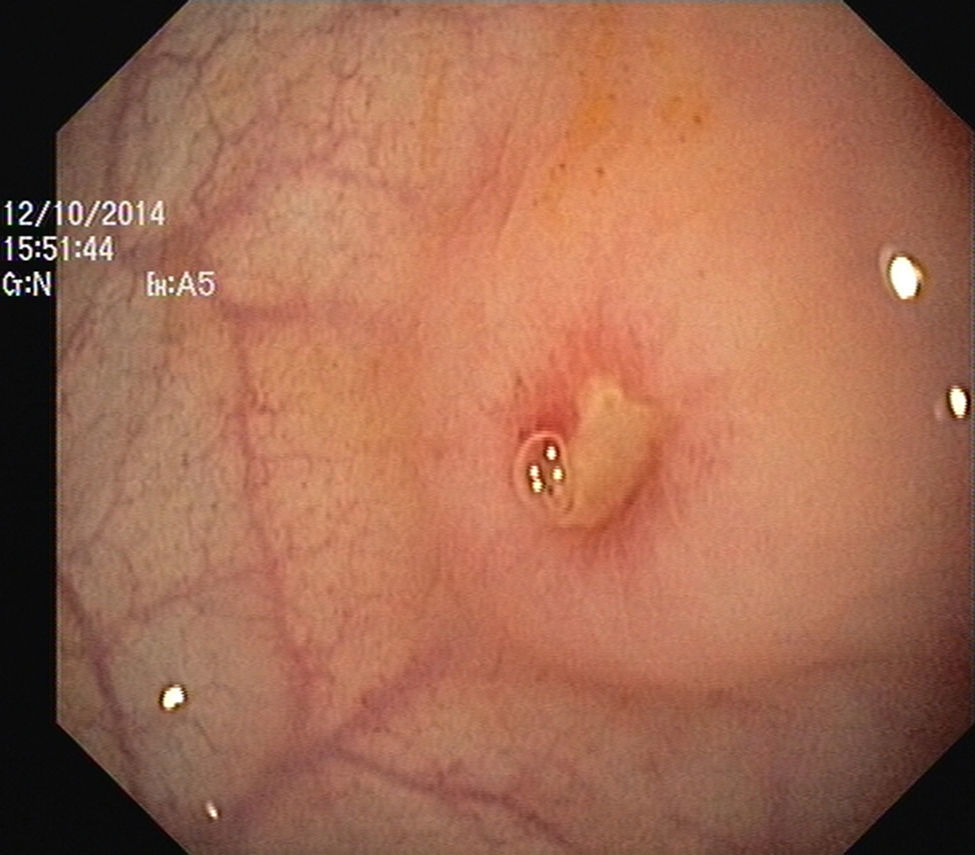

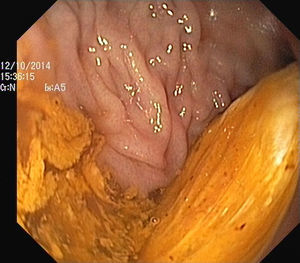

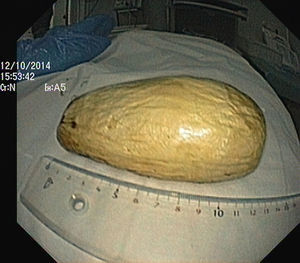

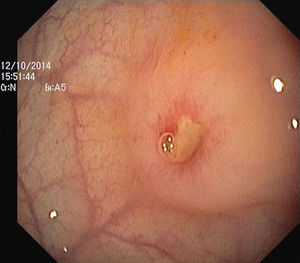

The authors report the case of a 37 year-old man, resident in prison, that was brought to the emergency room, with a suspected six day rectal foreign body retention, that the patient stated to be a deodorant cap. There was no relevant medical history except for prior consumption of drugs, and the guards who accompanied him denied current possession of illicit substances. The patient reported abdominal cramping pain and absence of stools for five days even after the use of enemas. Physical examination was unremarkable, including digital rectal inspection. In this context, an abdominal radiograph was requested and it revealed the presence of a foreign body in the small pelvis and a moderately dilated colon, without other changes (Fig. 1). In this moment, the patient still denied retention of a drug pack, even after having been warned that, in such case, its rupture could have serious consequences. So it was decided to perform a flexible sigmoidoscopy, without sedation. At 30cm from the anal verge it was noted the presence of a flexible, yellow, opaque, oval object, with 12cm in its major axis occupying the entire intestinal lumen (Fig. 2). After multiple attempts with a snare and subsequently a net, the object was finally and smoothly removed with a foreign body's forceps (Fig. 3). The underling mucosa exhibited a white base ulcer with swollen edges (Fig. 4). When asked again, the patient admitted that the object was in fact hiding a syringe for further use. However, we could not confirm its content due to legal issues. Once there were no immediate complications, the patient was then discharged.

Retained rectal foreign bodies are not an uncommon condition, and frequently present a difficult diagnostic and management dilemma. This is often because of the delayed presentation, wide variety of objects that cause the damage, and the wide spectrum of injury patterns that range from minimal mucosal injury to free intraperitoneal perforation, sepsis, and even death.1 Retained rectal foreign bodies are usually related to anal sexual behaviour.2 The important factors in dealing with these patients is fivefold: careful history and physical examination with respect for what is often an embarrassing problem, a radiographic evaluation (including computed tomography in doubtful cases or potentially difficult approach situations), a high index of suspicion for any evidence of toxicity that suggests perforation requiring emergent laparotomy, a creative approach to nonoperative removal using tools originally designed for other uses, and appropriate short-term follow-up to detect any delayed perforation, which may be a life-threatening problem.3 In this case, as there was previous drug consumption, a situation of body packing could not be totally excluded. In a prior review concerning drug packets ingestion, endoscopic removal is referred as a therapeutic option and is a reasonable alternative to surgery in particular situations.4 However, there is no evidence if this approach can be applied in suspected rectal retention of drug packers. Once the patient and the guards denied any possession of drugs, and given the clinical stability and the radiological findings, endoscopic removal was decided, keeping the patient without sedation. However we performed a second look, as it is mandatory after an anorectal foreign body removal to exclude bowel injury and ensure that the patient has not inserted more than one foreign body. This can be especially important in the presence of objects that migrate proximally, making it inaccessible to proctologic examination. Patients with mucosal abrasion, tears and edema may have to be admitted for a period of observation.5

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.