To describe the microorganisms present on surface areas of surgical rooms, in a medium-sized hospital in Sao Paulo state (Brazil).

Materials and methodSixty samples were collected with the aid of sterile swabs soaked in peptone water and rubbed into quadrants of 20cm2. The surfaces investigated were: medication tables, surgical tables, marble countertops and air conditioning grilles.

ResultsStaphylococcus aureus, coagulase negative, was the microorganism most frequently found on the surgical tables and on the medication tables (50.7% of the samples). This microorganism is also the most frequent cause of post-surgical infection at the same hospital.

ConclusionsProphylactic measures should include proper hand washing, the use of personal protective equipment, appropriate uniforms, and cleaning and sterilization of surface and medical and hospital equipment.

Describir los microorganismos presentes en las superficies del área de quirófanos de un hospital de tamaño medio en el estado de Sao Paulo (Brasil).

Materiales y métodosSe recolectaron y cultivaron 60 muestras con la ayuda de hisopos estériles en agua peptonada y aplicadas sobre cuadrantes de 20cm2. Las superficies investigadas fueron: tabla de medicamentos, mesa operatoria, terminaciones de mármol de la sala y grillas del aire acondicionado.

ResultadosEl organismo aislado de manera más frecuente fue Staphylococcus aureus coagulasa negativa y se encontró sobre la mesa operatoria y en la mesa de drogas (50,7% de las muestras). Este es el microorganismo reportado como la causa más frecuente de infecciones post-quirúrgicas en el mismo hospital.

ConclusionesLas medidas profilácticas deben incluir un apropiado lavado de manos, uso de equipo personal protector y limpieza y esterilización del equipo médico y hospitalario y de las superficies de trabajo.

The Ministry of Health of Brazil, defined health-care associated infections (HAIs) as any infection acquired after admission of the patient which become manifested during hospitalization or after 72h of hospital admission, or even after discharge.1–3 However, it is important to note that infections developed in the first year after surgery can also be considered as HAIs.2,3 Among the main factors reported in the literature for acquiring HAIs can be mentioned older age, malnutrition, obesity, diabetes mellitus, infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), the presence of distant infectious focus and previous arthroscopy or arthroplasty infection. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis also have a higher risk of postoperative infections, being estimated to be three to eight times higher than in other patients.4

A study related to orthopedic implants found that the majority of infections are due to Gram-positive facultative aerobic, predominantly Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis (44–50%).6 Yet, in the case of orthopedic infections, these should be treated with antibiotics that have action in the hospital microbiota service in which surgery was carried out, even before results of culture are available.4 For this reason there is a constant need for information of the microorganisms circulating in surgical rooms in order to orientate preventive measures, education and control to reduce nosocomial infection rates.5

This study was undertaken to characterize the microorganisms that are present in the surface of operating rooms and to determine their profile of antimicrobial resistance. This will afford valuable information to propose preventive measures in the hospitals for HAIs.

Materials and methodsThis study was carried out in the pre-operative elective orthopedic surgery rooms in a surgical center of a midsize hospital in São Carlos (Sao Paulo, Brazil). The project was evaluated and approved by the ethics institutional board and the internal Infection Control and Management of Nursing committee. The hospital has 360 beds, 20 of them dedicated to intensive care. Monthly, the hospital attends about 2500 urgencies, 800 surgery and 200 deliveries. Approximately 100 orthopedical surgeries are done each month.

The microbiological samples were collected in the following areas: medication on the table, operating table, a table of drugs and marble countertops. In total, 60 samples from November 2010 to February 2011 were collected. We used a swab (sterile wood, approximately 10cm long, with a cotton sheath on one end) soaked in sterile water and sterile peptone (PA), and then pressed and rubbed on 20cm2 of each surface area during 5s. The swab was identified and placed within a test tube containing PA by using aseptic procedures and transported in polystyrene boxes containing ice to the Laboratory of Teaching, Research and Diagnostic in Microbiology. The transport period does not exceeded 2h until the start of the microbiological analysis.

The culture media was prepared according to the manufacturer's instructions and distributed as required on plates or in sterile test tubes. All swabs were incubated in brilliant green agar, MacConkey agar, mannitol salt agar, cetrimide agar and blood agar. After incubation for 24–48h at 37°C, typical colonies for each of the bacterial groups were evaluated and classified. For detecting coagulase-positive bacteria we used Mannitol Salt Agar. Mannitol positive colonies (small and yellow isolates) were transferred to trypticase soy agar (TSA), incubated at 37°C for 24h and kept under refrigeration (7°C). From TSA colonies we prepared some smears of the samples on slides that were fixed and Gram-stained. Thereafter, we made a screening of samples containing clusters of Gram-positive cocci that were submitted to the coagulase test. The reagents used were of commercial origin. Tubes with plasma coagulation were considered to be positive for coagulase. Results are expressed as the mean and standard deviation for continuous variables and N (%) for categorical variables.

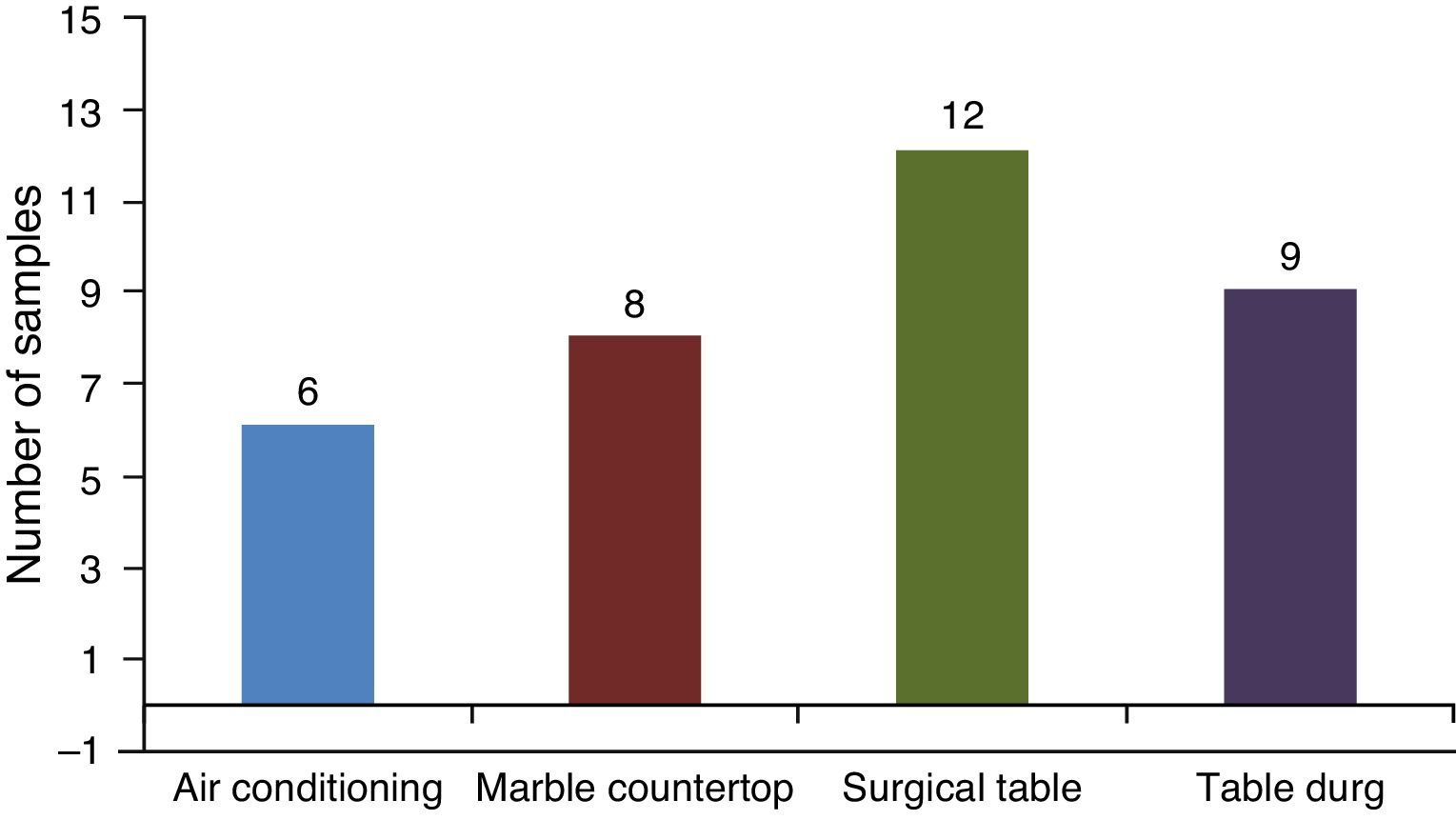

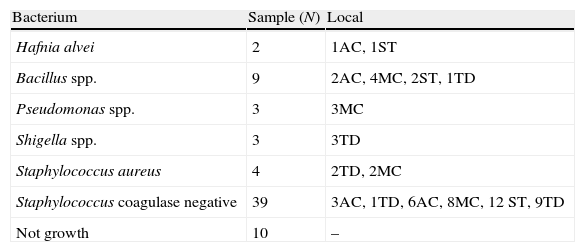

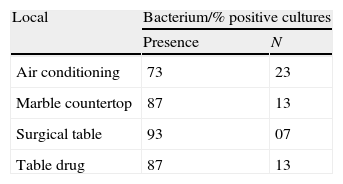

ResultsIn total, 60 samples in different areas of the surgical center were studied with a varied distribution of microorganisms (Tables 1 and 2). There was growth of bacteria in 73% of samples collected from the bars of air conditioners, 87% of marble countertops and table of drugs and 93% of surgical tables (Table 2). By analyzing the locations where samples were collected, its percentage of contamination was of 40%, 53%, 80% and 60% in air conditioning, marble countertops, operating table and table of drugs, respectively.

Mesophilic aerobic bacteria according to sample locations in a midsize Surgery Center Hospital in São Carlos (SP).

| Bacterium | Sample (N) | Local |

| Hafnia alvei | 2 | 1AC, 1ST |

| Bacillus spp. | 9 | 2AC, 4MC, 2ST, 1TD |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 3 | 3MC |

| Shigella spp. | 3 | 3TD |

| Staphylococcus aureus | 4 | 2TD, 2MC |

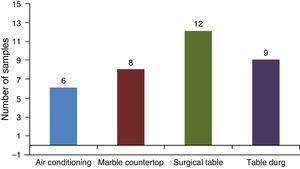

| Staphylococcus coagulase negative | 39 | 3AC, 1TD, 6AC, 8MC, 12 ST, 9TD |

| Not growth | 10 | – |

AC, air conditioner; MC, marble countertops; ST, surgical tables; TD, table of drugs.

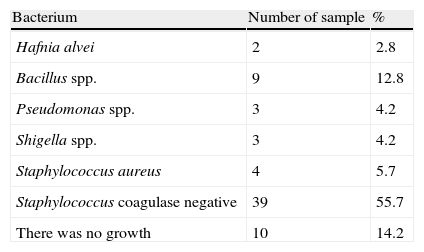

Staphylococcus species identification was obtained by simplified classical methodology.8 According to this, 5.7% and 55.7% of S. aureus were coagulase positive and coagulase negative isolates, respectively. Some Staphylococcus samples could not be identified at species level, because there was not enough growth of bacteria to obtain usable amounts. The surgical table showed the higher percent of Staphylococcus-contaminated surfaces (20%) when compared to other locations in this study (Fig. 1). Overall, there was a predominance of Gram positive microorganisms. S. aureus coagulase negative was the microorganism most frequently found (50.7% of the samples) on the surgical table and on the tables of drugs.

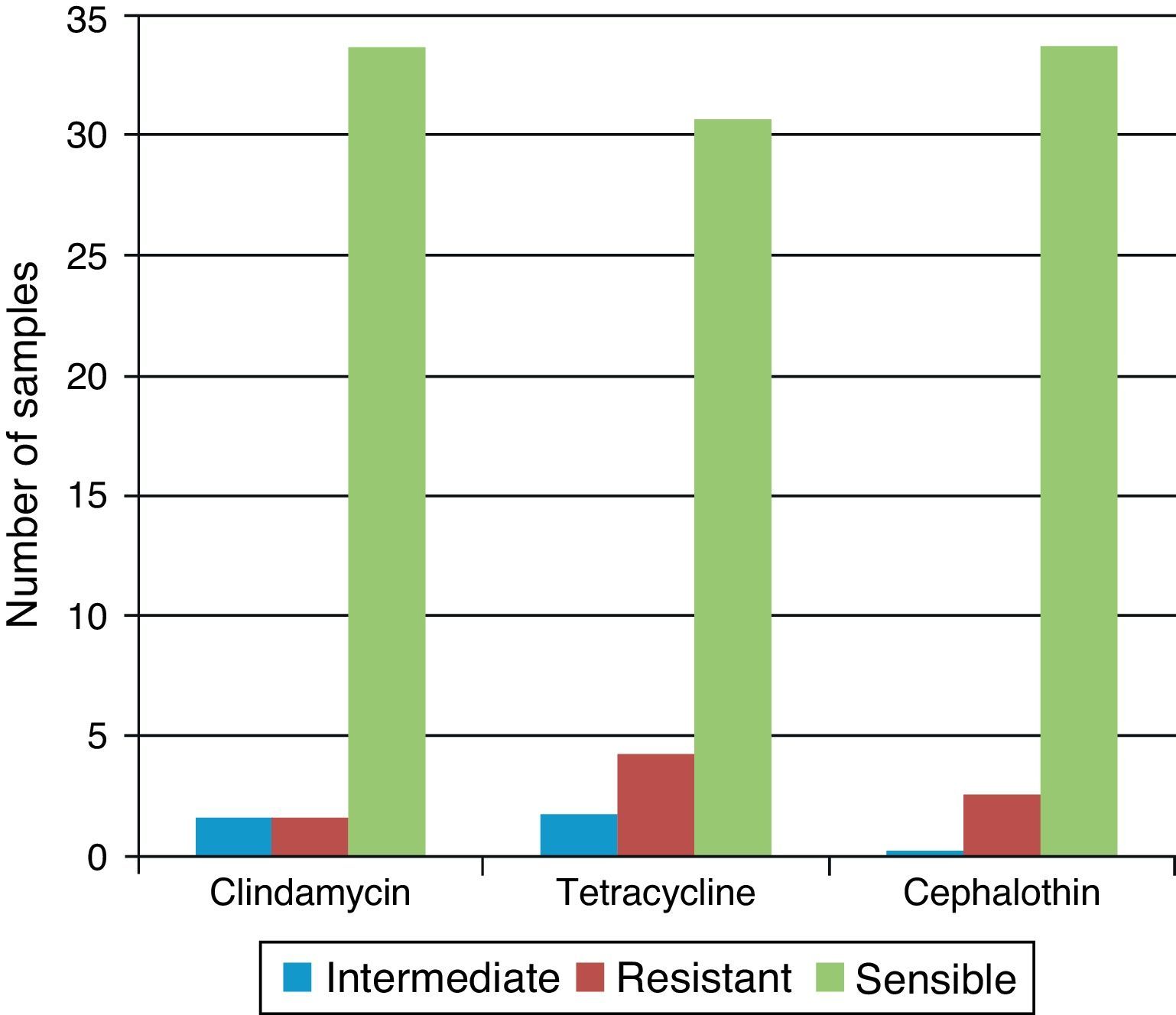

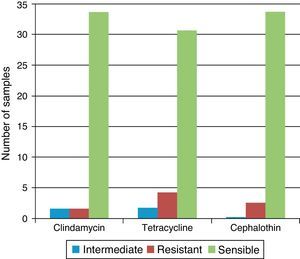

50% of the strains of Staphylococcus spp. and S. aureus were resistant to penicillin, amoxicillin and oxacillin, whereas 50% were susceptible or with intermediate susceptibility for cephalothin, clindamycin, and tetracycline. Of the four samples where Staphylococcus coagulase negative were isolated, three were found in air conditioning grills and in one sample of the table of medication. All were resistant to Novabiocin. All of the 35 Staphylococcus coagulase negative strains were resistant to penicillin G, oxacillin and amoxicillin. One sample was resistant to clindamycin, four samples presented resistance to cephalothin and two were resistant to tetracycline. In 83% of the samples we detected some other bacterial species: Hafnia alvei, Pseudomonas spp., Shigella spp, S. aureus, Staphylococcus coagulase negative and Staphylococcus spp. (Table 3).

Between Gram-negative bacteria, we isolate H. alvei and Shigella spp. Pseudomonas spp. was obtained in selective medium cetrimide-agar in three samples of marble countertops. All these bacteria were susceptible to aztreonam, metilmicin, gentamicin, and amikacin (Fig. 2).

DiscussionIn our study Staphylococcus spp. was the most frequent bacteria isolated on surfaces of the surgical room area. This is in agreement with previous reports where S. aureus is the most common agent isolated from patients readmitted after surgery.9,10S. aureus has been found in surgical materials and it has been also reported that half of the strains shown multidrug resistance.9,10 The large prevalence of this microorganism in hospital surgical rooms could be attributed to his association with human nose and hands. Other authors reported similar results.7S. aureus is the microorganism most frequently found in the case of osteomyelitis. S. aureus is capable of producing a series of factors such as hydrolytic exotoxins that adhere to endothelial cells, facilitating his penetration into tissues.11 According to some authors, cardiac surgery can result in osteomyelitis of the sternum, where coagulase-negative staphylococci are the most frequent cause.11

In our hospital, the prophylaxis is indicated for joint prosthesis and for osteosynthesis. In surgeries that involve only soft tissue, muscle tissue and tendons, the prophylaxis is not recommended. For allergic patients and early operations, vancomycin and gentamicin are the antibiotics of first choice. In open fracture, the patients should receive amoxicillin and cefazolin or sulfabactam during 5 days, according to trauma severity and patient outcomes.11 Previous reports from our hospital showed that the main microorganisms diagnosed in surgical site infections were Klebsiella pneumoniae (22%), S. aureus (20%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (14%), Acinetobacter sp. (13%), Escherichia coli (10%), Enterobacter sp. (9%) and Candida sp. (9%).12 Therefore the bacteria found in surgical infection follows partly to those detected on the surfaces of surgical room area in this study. In another study conducted in air samples from a Brazilian hospital, high levels of Staphylococcus spp. (86.9%) were detected.6 Higher levels of contamination of the surfaces may occur by factors such as greater movement of people in the premises or failure to disinfect surfaces. A previous study13 showed the importance of airborne microorganisms in orthopedic surgery. This is particularly important when considering S. aureus methicilin resistant strains.7

Regarding the antimicrobial tests, similar results were found in this study, when considering the isolation of Staphylococcus spp. in hospital. Researchers found that over 13% of the isolates were resistant to all antibiotics except vancomycin, teicoplanin, and linezolid.8

The infection is considered a risk to any surgery, but is of particular concern to orthopedic patient, because of the high risk of osteomyelitis, leading to prolonged treatment with intravenous antibiotics. However, if this particular case occurs, the infected bone, prosthesis or internal fixation device should be removed by surgery.14 Lima and Oliveira (2010)4 showed that several pre-operative preventive measures in orthopedic surgery such as the restriction in hair removal and not use of depilatory creams and cutting equipment and appropriate antibiotic prophylaxis (starting from time zero to the 60min before induction of anesthesia and maintained for 24h), reduces HAIs. The use of antibiotics should be controlled by prescription, providing information and data to all medical staff.

Prophylactic measures such as awareness of staff regarding proper hand washing; use of personal protective equipment, appropriate uniforms, and cleaning and sterilization of medical and hospital equipment, seems to be necessary. It is very important to carry out the practice of surface cleaning and handling hospital waste appropriately. Other important practices are the appropriate use of surgical masks and caps, leaving no hair in sight, surgical gown in good usage without tears or lint – for example, as well to avoid as much traffic overcrowding in the operating room by closing the doors when they are not in use.

It must be considered the adequate air conditioning usage in the room of the surgical center. Optionally, the use of laminar flow filters for air conditioning must be given constant attention, contributing to the prevention of the spread of potentially pathogenic microorganisms and, consequently, minimizing hospital infections. When controlling all the mechanisms of action of the air in indoor environment, this can prevent outbreaks and infection, thus contributing to lower hospital costs and, most importantly of all, the patient will have a better quality of life without physical limitations or reductions.15 Thus, it can be expected that the nurse will play a very important role for the hospital infections control by developing activities such as teaching and research in different areas. It is needed to develop new research to evaluate the efficacy of these recommendations.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare not to have any conflict of interest.