Objective: Many patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators experience depressive symptoms. In addition, avoidance behavior is a common problem among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. We examined the association between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptoms in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Method: We conducted a single-center, cross-sectional study with self-completed questionnaires between May 2010 and March 2011. We measured avoidance behaviors (avoidance of places, avoidance of objects, and avoidance of situations) and depressive symptoms (using the Beck Depression Inventory, Version II) in 119 participants. An avoidance behaviors instrument was developed for this study and we confirmed its internal consistency reliability. Results: Ninety-two (77.3%) patients were aged older than 50 years, and 86 (72.3%) were men. Fifty-one (42.9%) patients reported “avoidance of places”, 34 (28.6%) reported “avoidance of objects”, and 63 (52.9%) reported “avoidance of activity”. Avoidance behavior was associated with increased odds for the presence of depressive symptoms (OR 1.31; 95% CI 1.06–1.62). Conclusions: This was the first study to identify the relationship between avoidance behavior and depressive symptoms among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators; however, there are a few methodological limitations.

Objetivo: Muchos pacientes con desfibriladores cardioversores implantables experimentan síntomas depresivos. Además, la conducta de evitación es un problema común entre estos pacientes. El objetivo fue examinar la asociación entre las conductas de evitación y síntomas depresivos en pacientes con desfibriladores cardioversores implantables. Método: Se llevó a cabo un estudio transversal en un único centro entre mayo de 2010 y marzo de 2011. Mediante autoinformes se midieron conductas de evitación (evitación a lugares, evitación a objetos y evitación a situaciones) y síntomas depresivos (mediante el Inventario de Depresión de Beck, Versión II) en 119 participantes. El instrumento de evitación se desarrolló para este estudio con adecuada fiabilidad de consistencia interna. Resultados: Noventa y dos pacientes (77,3%) tenían más de 50 años y 86 pacientes (72,3%) eran hombres. Cincuenta y un pacientes (42,9%) informaron de “evitación a lugares”, 34 pacientes (28,6%) informaron de “evitación a objetos” y 63 pacientes (52,9%) informaron “evitación a actividad”. La conducta de evitación se asoció con un aumento en la probabilidad de síntomas depresivos (OR 1,31; IC del 95%, 1,06-1,62). Conclusiones: Este es el primer estudio para identificar la relación entre la conducta de evitación y síntomas depresivos en pacientes portadores de desfibriladores cardioversores implantables, aunque existen algunas limitaciones metodológicas.

An implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) is an electronic internal device that can detect and correct fatal arrhythmia. The use of ICDs, including the cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator (CRT-D) for patients with heart failure, significantly reduces mortality from sudden cardiac death compared with anti-arrhythmic drug therapy (Alba et al., 2013; Chen, Ling, Kikuchi, Yin, & Krucoff, 2013; Connolly et al., 2000; Tan, Wilton, Kuriachan, Sumner, & Exner, 2014). However, some patients with ICDs experience psychological distress due to fear of blast or strong pain by electric shock (de Ornelas Maia, Soares-Filho, Pereira, Nardi, & Silva, 2013; Heller, Ormont, Lidagoster, Sciacca, & Steinberg, 1998). According to a recent systematic review, 5–41% of patients reported depressive symptoms and 8–63% reported anxiety symptoms (Magyar-Russell et al., 2011).

Depressive symptoms are a particularly difficult psychological problem for patients with ICDs. Indeed, 11–28% of all such patients have major depressive disorder (Magyar-Russell et al., 2011) that follows a severe clinical course. Several studies have reported that depressive symptoms were a risk factor for poor adherence (Luyster, Hughes, & Gunstad, 2009), arrhythmic episodes (Tzeis et al., 2011), phantom shock (Starrenburg, Kraaier, Pedersen, Scholten, & Van Der Palen, 2014), rehospitalization (Shalaby, Brumberg, El-Saed, & Saba, 2012), and increased mortality rates (van den Broek et al., 2013; Whang et al., 2005). In contrast, some earlier studies suggested that depressive symptoms are predicted by being younger, being female, having poor social support (e.g., living alone), having a poor physical condition (e.g., presence of heart failure), and electric shock events among patients with ICDs (Moryś, Pąchalska, Bellwon, & Gruchała, 2016). However, the personal factors that are related to depressive symptoms have not yet been fully defined, although factors related anxiety symptoms have been increasingly clarified (Sears & Conti, 2002).

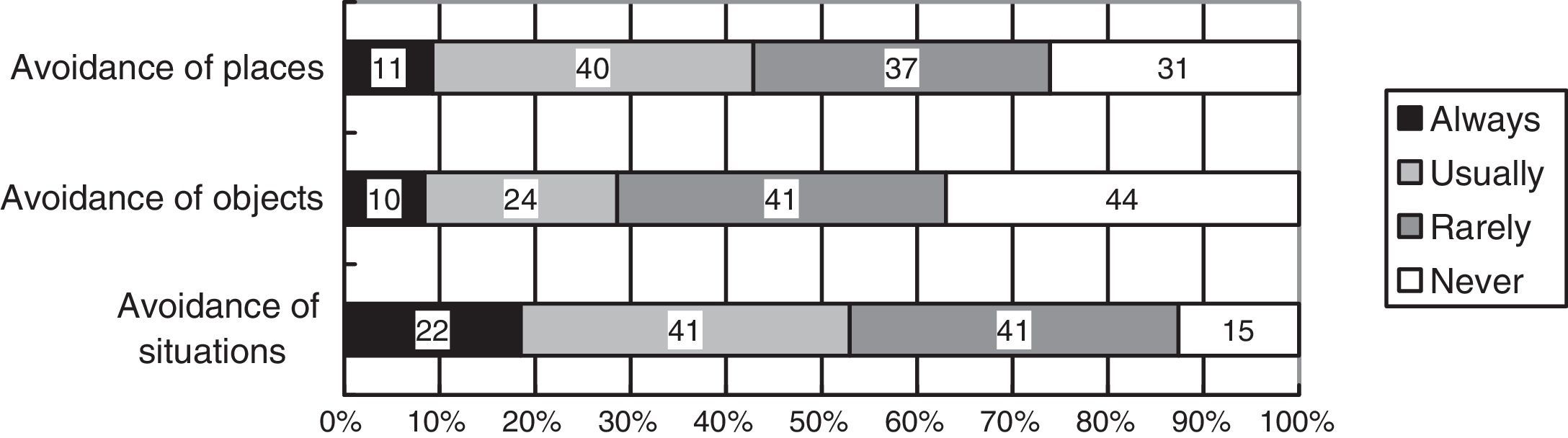

Avoidance behavior is one of the most common symptoms for patients with ICDs (Godemann et al., 2001, 2004; Ingles, Sarina, Kasparian, & Semsarian, 2013; Morken et al., 2014). Patients with avoidance behaviors characteristically reduce their routine behaviors such as using cell phones, taking showers, or going out because they fear electric shock from an ICDs (Cutitta et al., 2014). Indeed, 17% of patients reported “avoidance of places”, 27% reported “avoidance of objects”, and 39% reported “avoidance of situations” (Lemon, Edelman, & Kirkness, 2004). Avoidance behavior promotes anxiety and is a symptom of anxiety disorders such as panic disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder (Godemann et al., 2004; Pauli, Wiedemann, Dengler, Blaumann-Benninghoff, & Kühlkamp, 1999; Sears & Conti, 2002; von Känel, Baumert, Kolb, Cho, & Ladwig, 2011). In the general population, research on behavioral activation treatment has suggested that avoidance behaviors are related to depressive symptoms (Jacobson, Martell, & Dimidjian, 2006; Jacobson & Newman, 2014). However, no study has examined the association between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptoms in patients with ICDs; therefore, we examined (1) the frequency of avoidance behaviors and (2) the association between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptoms in patients with ICDs. Our primary hypothesis was that patients who have a strong avoidance tendency would be more likely to have depressive symptoms.

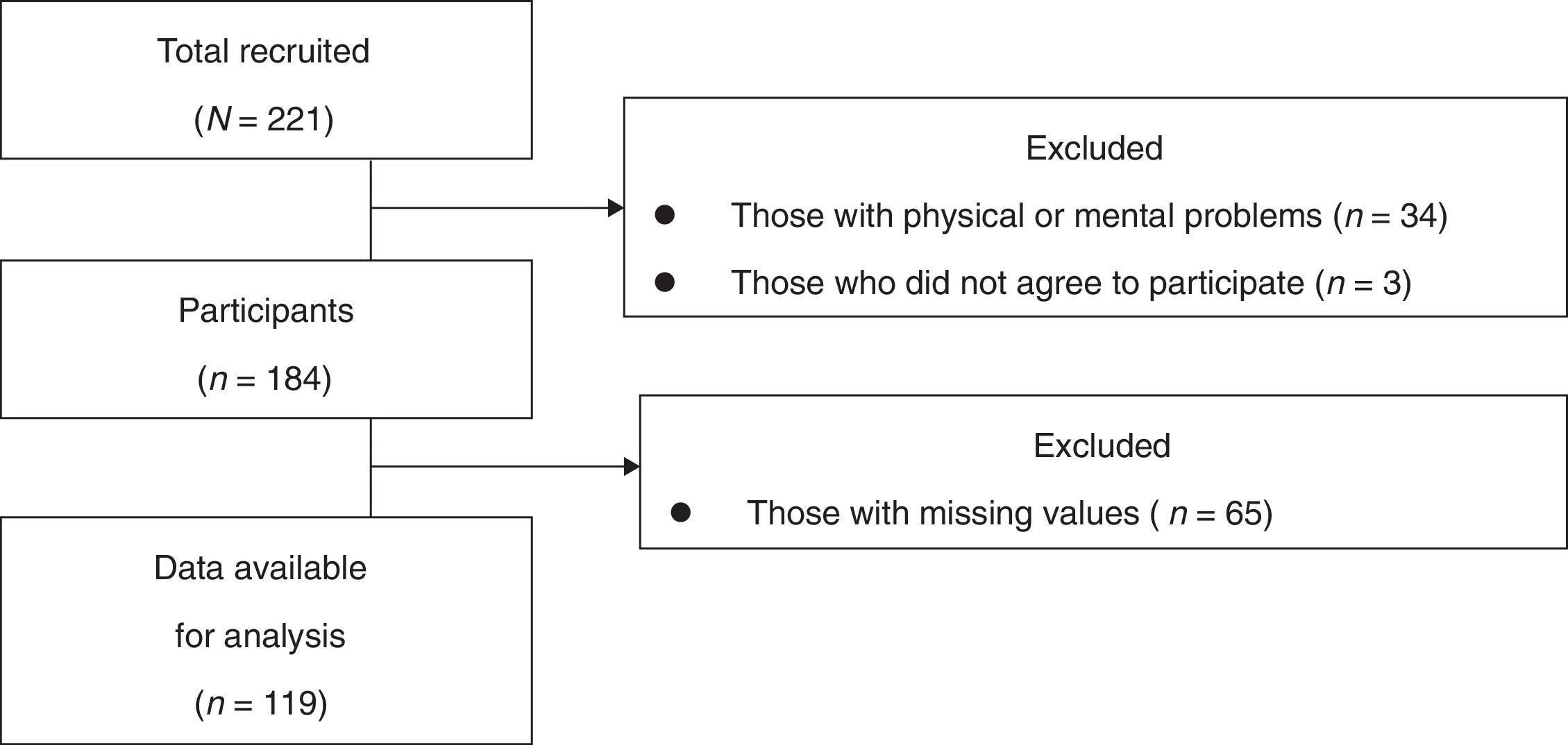

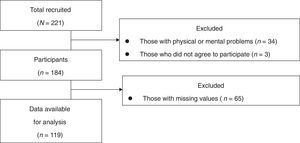

MethodParticipantsWe conducted a single-center, cross-sectional study using self-reported questionnaires. The data were collected from outpatients or inpatients in Department of Cardiology, Tokyo Women's Medical University (TWMU) Hospital between May 2010 and March 2011. Patients who have defibrillators (ICDs or CRT-Ds) were included in this study. Some patients were excluded: those were judged to have severe physical or mental problems (e.g., serious symptoms of heart failure, delirium, or dementia) or insufficient literacy skills by cardiologists, and patients older than 90 years. Sixty-five patients were excluded because they did not complete the questionnaire, resulting in data for 119 (response rate: 64.7%) being available for analysis.

InstrumentsDemographic and clinical characteristics. Demographic and clinical characteristics were collected from patients’ medical records to identify potential confounders for depressive symptoms. Data included age, sex, living situation, employment status, cardiac diseases and complications, and information about devices (i.e., type, reason for implantation, period of implantation, and experience of electric shocks).

Avoidance behaviors. Avoidance behaviors were evaluated using questionnaires we developed for a series of our studies based on a previous study (Lemon et al., 2004). This instrument had been currently under development. The questionnaire included three items: (1) “How often do you avoid places (e.g., trains or buses) where you think you are likely to get a shock?” (avoidance of places); (2) “How often do you avoid objects (e.g., cell phones or microwave) where you think you are likely to get a shock?” (avoidance of objects); and (3) “How often do you avoid situations (e.g., taking a shower) where you think you are likely to get a shock?” (avoidance of situations). Each item was scored on a four-point Likert-type scale (always=3, usually=2, rarely=1, and never=0). The total score of the three items was denoted as avoidance behaviors, and a higher score amounted to greater avoidance (range: 0–9). The content validity of the questionnaire was discussed among researchers including cardiologists, psychiatrists, and clinical psychologists. The test-retest interclass Correlation Coefficients (ICC)=.61, and Cronbach's alpha=.60 in our data for another previous study among Japanese outpatients with ICDs (Ichikura et al., 2015).

Depressive symptoms. Depressive symptoms were evaluated using the Beck Depression Inventory, Version II: BDI-II (Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996; Kojima et al., 2002). The BDI-II measures the severity of depressive symptoms rather than the presence of a depressive episode. It is a 21-item self-rated questionnaire for depressive symptoms. It utilizes a four-point Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 3 (overall score 0–63). A score of 0–13 is classified as minimal depressive symptoms, 14–19 as mild, 20–28 as moderate, and 29–63 as severe. We defined a score of more than 14 points as indicating patients with depressive symptoms. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire were sufficiently supported in some earlier studies (Beck et al., 1996), and Cronbach's alpha=.92–.93.

ProcedureWe conducted continuous sampling from all eligible patients in the TWMU Hospital. Two research students (KI and SM) who were not involved in medical practice informed patients about the aim of this study and obtained their written consent. The questionnaires were completed and collected from patients after they agreed to participate. The researchers assisted those patients who were unable to write the answers themselves because of physical problems such as dysopia or upper-limb dysfunction to keep selection bias at a minimum.

All the procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committees on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. All participants were volunteers and were not provided with any incentives to participate. This study assured participant anonymity and was approved by the ethics committee of TWMU (1832) and Waseda University (2012-157).

According to some past studies, depressive symptoms occur in 24–46% of patients with ICDs (Godemann et al., 2004; Lang et al., 2014; Sears & Conti, 2002). Using the above information as our reference range for depressive symptoms and assuming depressive symptoms in patients with ICDs without avoidance behaviors to be 20% and with avoidance behaviors to be 40%, we needed 164 participants for 80% power and 5% significance levels. One hundred and ninety-seven patients was deemed sufficient, even if 20% of patients did not agree to participate or did not complete the questionnaire (Sato, 2015).

Statistical analysisFirst, we examined the frequency distributions of all demographic and clinical characteristics. Second, we examined the Cronbach's alpha coefficient as a measure of the internal consistency reliability of avoidance behaviors scores. Then, we examined the frequency of three avoidance behaviors and compared each other using Cochran's Q test. Third, we estimated the odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of avoidance behaviors for the presence of depressive symptoms (BDI-II ≥ 14) using logistic regression models. Then, we sequentially introduced groups of variables into the model: first demographic and clinical variables and then avoidance behaviors, because these are known from previous studies to be associated with depressive symptoms (Moryś et al., 2016). The independent variables included in this model were based on a priori clinical judgment and the existing literature, and included 1) age, 2) sex, 3) family structure (living alone vs. living with family), 4) employment status, 5) presence of heart failure, and 6) having experienced electric shock. We used a likelihood ratio test to determine the statistical significance of interaction terms in the logistic regression models. Multicollinearity was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF; Katz, 2003). A VIF exceeding 10 was regarded as indicating serious multicollinearity, and values greater than 4.0 may be a cause for concern (Katz, 2003). We also examined an identical logistic regression model except for patients with CRT-Ds to show that we can achieve consistent results in the subgroup. We conducted all analyses using R version 2.15.1. with the R package “rpsychi” (R Core Team, 2012).

ResultsParticipants’ characteristicsUnfortunately, we stopped recruiting before reaching the required number of participants because Waseda University ceased the dispatch of research students to TWMU hospital because of the Great East Japan Earthquake in March 2011. Of the 221 patients with an ICD or CRT-D, data from 184 participants were considered potentially eligible (Figure 1).

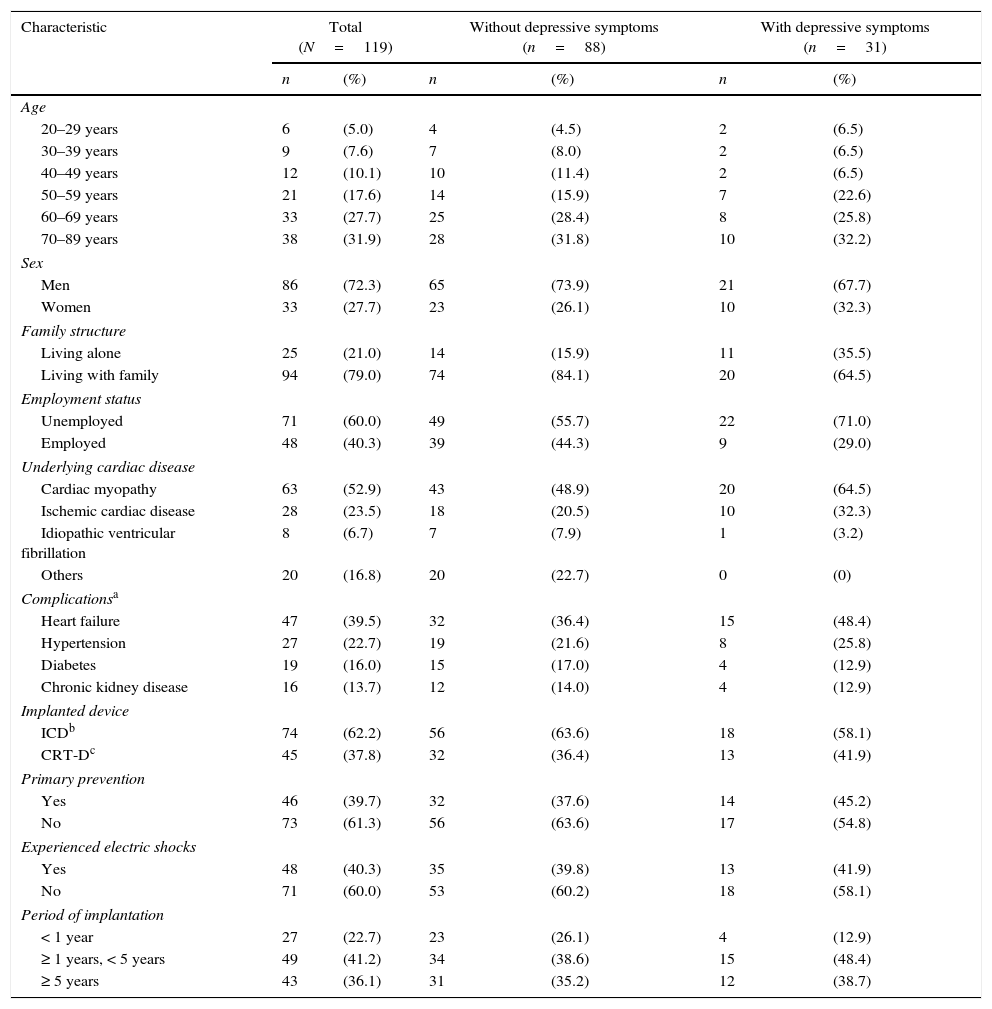

We compared the demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (Table 1). Thirty-one (26.1%) patients had depressive symptoms (BDI ≥ 14) among the ICD recipients. Ninety-two (77.3%) were more than 50-years-old, 86 (72.3%) were men, and 25 (21.0%) lived alone. More than half of all participants had cardiac myopathy (n=63, 52.0%), and 47 (39.5%) had heart failure.

Participants’ characteristics.

| Characteristic | Total (N=119) | Without depressive symptoms (n=88) | With depressive symptoms (n=31) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Age | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 6 | (5.0) | 4 | (4.5) | 2 | (6.5) |

| 30–39 years | 9 | (7.6) | 7 | (8.0) | 2 | (6.5) |

| 40–49 years | 12 | (10.1) | 10 | (11.4) | 2 | (6.5) |

| 50–59 years | 21 | (17.6) | 14 | (15.9) | 7 | (22.6) |

| 60–69 years | 33 | (27.7) | 25 | (28.4) | 8 | (25.8) |

| 70–89 years | 38 | (31.9) | 28 | (31.8) | 10 | (32.2) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Men | 86 | (72.3) | 65 | (73.9) | 21 | (67.7) |

| Women | 33 | (27.7) | 23 | (26.1) | 10 | (32.3) |

| Family structure | ||||||

| Living alone | 25 | (21.0) | 14 | (15.9) | 11 | (35.5) |

| Living with family | 94 | (79.0) | 74 | (84.1) | 20 | (64.5) |

| Employment status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 71 | (60.0) | 49 | (55.7) | 22 | (71.0) |

| Employed | 48 | (40.3) | 39 | (44.3) | 9 | (29.0) |

| Underlying cardiac disease | ||||||

| Cardiac myopathy | 63 | (52.9) | 43 | (48.9) | 20 | (64.5) |

| Ischemic cardiac disease | 28 | (23.5) | 18 | (20.5) | 10 | (32.3) |

| Idiopathic ventricular fibrillation | 8 | (6.7) | 7 | (7.9) | 1 | (3.2) |

| Others | 20 | (16.8) | 20 | (22.7) | 0 | (0) |

| Complicationsa | ||||||

| Heart failure | 47 | (39.5) | 32 | (36.4) | 15 | (48.4) |

| Hypertension | 27 | (22.7) | 19 | (21.6) | 8 | (25.8) |

| Diabetes | 19 | (16.0) | 15 | (17.0) | 4 | (12.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 16 | (13.7) | 12 | (14.0) | 4 | (12.9) |

| Implanted device | ||||||

| ICDb | 74 | (62.2) | 56 | (63.6) | 18 | (58.1) |

| CRT-Dc | 45 | (37.8) | 32 | (36.4) | 13 | (41.9) |

| Primary prevention | ||||||

| Yes | 46 | (39.7) | 32 | (37.6) | 14 | (45.2) |

| No | 73 | (61.3) | 56 | (63.6) | 17 | (54.8) |

| Experienced electric shocks | ||||||

| Yes | 48 | (40.3) | 35 | (39.8) | 13 | (41.9) |

| No | 71 | (60.0) | 53 | (60.2) | 18 | (58.1) |

| Period of implantation | ||||||

| < 1 year | 27 | (22.7) | 23 | (26.1) | 4 | (12.9) |

| ≥ 1 years, < 5 years | 49 | (41.2) | 34 | (38.6) | 15 | (48.4) |

| ≥ 5 years | 43 | (36.1) | 31 | (35.2) | 12 | (38.7) |

Note.

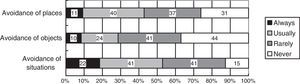

The Cronbach's alpha coefficient was .65 for the avoidance behaviors summary score. The frequency of patients’ avoidance behaviors is shown in Figure 2. Fifty-one (42.8%) patients reported “avoidance of places” with responses of “always” or “usually”, 34 (28.6%) reported “avoidance of objects”, and 63 (52.9%) reported “avoidance of situations”. According to the Cochran's Q test, the frequency of avoidance of places and avoidance of situations were significantly higher than avoidance of objects was (Q=20.55, p<.05).

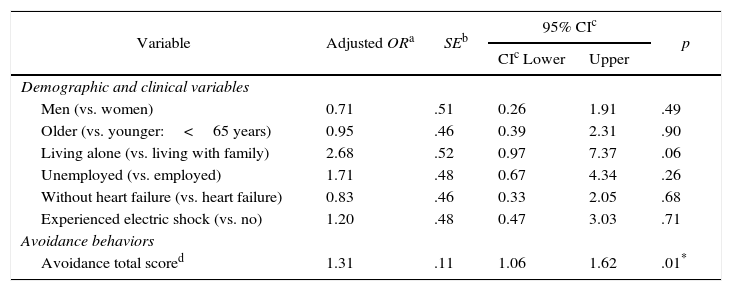

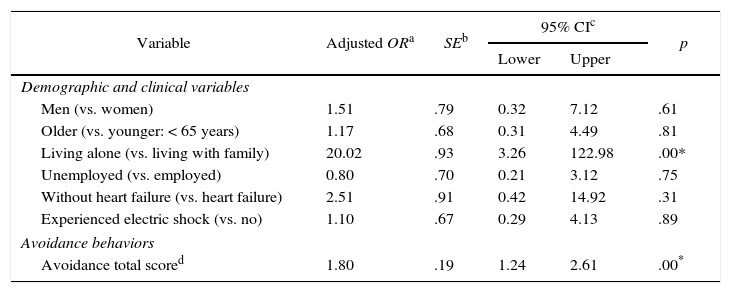

Association between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptomsThe logistic regression analysis indicated that avoidance behaviors was related to depressive symptoms (Table 2), with an odds ratio of 1.31 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.06–1.62). In the likelihood ratio test, none of the interactions of the independent variables were significant. Evidence for multicollinearity was absent because the VIF for independent variables in this model was less than 4.0 (Table 2). The subgroup analysis also indicated that avoidance behaviors and living alone were associated with increased odds for depressive symptoms (OR=1.80, 95% CI: 1.24–2.61; OR=20.02, 95% CI 3.26–122.98) (Table 3).

Depressive symptoms among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillators (N=119).

| Variable | Adjusted ORa | SEb | 95% CIc | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIc Lower | Upper | ||||

| Demographic and clinical variables | |||||

| Men (vs. women) | 0.71 | .51 | 0.26 | 1.91 | .49 |

| Older (vs. younger:<65 years) | 0.95 | .46 | 0.39 | 2.31 | .90 |

| Living alone (vs. living with family) | 2.68 | .52 | 0.97 | 7.37 | .06 |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | 1.71 | .48 | 0.67 | 4.34 | .26 |

| Without heart failure (vs. heart failure) | 0.83 | .46 | 0.33 | 2.05 | .68 |

| Experienced electric shock (vs. no) | 1.20 | .48 | 0.47 | 3.03 | .71 |

| Avoidance behaviors | |||||

| Avoidance total scored | 1.31 | .11 | 1.06 | 1.62 | .01* |

Note.

Depressive symptoms only among patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (N=74).

| Variable | Adjusted ORa | SEb | 95% CIc | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Demographic and clinical variables | |||||

| Men (vs. women) | 1.51 | .79 | 0.32 | 7.12 | .61 |

| Older (vs. younger: < 65 years) | 1.17 | .68 | 0.31 | 4.49 | .81 |

| Living alone (vs. living with family) | 20.02 | .93 | 3.26 | 122.98 | .00* |

| Unemployed (vs. employed) | 0.80 | .70 | 0.21 | 3.12 | .75 |

| Without heart failure (vs. heart failure) | 2.51 | .91 | 0.42 | 14.92 | .31 |

| Experienced electric shock (vs. no) | 1.10 | .67 | 0.29 | 4.13 | .89 |

| Avoidance behaviors | |||||

| Avoidance total scored | 1.80 | .19 | 1.24 | 2.61 | .00* |

Note.

Our study yielded two major findings. First, our results demonstrated that avoidance of situations appeared in more than 50% of patients, and avoidance of situations and places occurred at a higher frequency compared with avoidance of objects. Second, our results demonstrate that avoidance behavior was associated with depressive symptoms among patients with ICDs, and the same result was also confirmed by the subgroup analysis model, which excluded patients with CRT-Ds.

One important consequence is that many patients suffer from avoidance behaviors, particularly from avoidance of situations and places. For example, agoraphobia (i.e., avoidance of places) was a very common problem of ICD patients (Godemann et al., 2004). Other studies showed that avoidance of situations, including physical exercise, sexual activity, or taking a shower, occurred frequently and directly interrupted patients’ daily life (Cutitta et al., 2014; Lemon et al., 2004). In addition, patients would like to cope with avoidance behaviors by fear of ICDs (Humphreys, Lowe, Rance, & Bennett, 2016). Therefore, avoidance of places and situations were difficult problems for patients with ICDs.

Another finding supports our primary hypothesis that the height of avoidance tendency is more likely to be associated with depressive symptoms. One explanation is that avoidance behaviors can enhance depressive symptoms and they are mediated by activation of catastrophic interpretations. Catastrophic thinking, such as a fear of dying increased by avoidance behaviors, is defined as a factor related to depressive symptoms per the second wave of cognitive theory (Beck, 1987; Kovacs & Beck, 1978). Another explanation is that avoidance behaviors can directly lead to depressive symptoms among patients with ICDs. According to some cognitive behavioral models for depressive symptoms, experiential avoidance naturally contributes to the worsening of depressive symptoms (Jacobson et al., 2006; Lesinsohn, Hoberman, Teri, & Hautzinger, 1985).

In contrast, the cause-and-effect relationship remains unclear due to the use of the cross-sectional method. Avoidance behaviors can occur because of depressive symptoms, or they can moderate the relationship between depressive and anxiety symptoms per the fear-avoidance model (Seekatz, Meng, Bengel, & Faller, 2015). Indeed, behavioral activation that is focused on avoidance behavior is typically an effective treatment for patients with depressive symptoms (Hunot et al., 2013). Therefore, avoidance behaviors could be amenable to treatment for patients with ICDs who at risk for depression.

Our study had several limitations. First, causality cannot be inferred due to the cross-sectional study design. Therefore, longitudinal or randomized controlled trials are needed in the future. Second, potential instrument bias and recall bias might exist due to our measures. The instrument of avoidance behaviors had not been standardized, and had only a three-items with a small range. Additionally, all measures comprised self-completed questionnaires. However, we evaluated content validity with sufficient discussion, and confirmed internal consistency reliability. Third, selection bias might have occurred due to implementing a single-center study in Japan. The hospital might have had a high frequency of severe heart diseases compared to other hospitals, which typically have 28% patients with cardiac myopathy (The Japanese Circulation Society, 2011). However, the hypothetical model was supported by the subgroup analysis that was conducted with patients with mild heart failure. Fourth, there was insufficient power because of the small sample size. We regret that our study was forced to stop recruiting due to the earthquake. Fifth, the logistic regression model assumed in this study was inadequate to determine the relationship between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptoms. We did not measure factors for depressive symptoms such as family history of depressive disorder.

Our study suggests that avoidance behaviors may be a potential controllable risk factor for patients with depressive symptoms. Sears and Conti (2002) indicated there is a relationship between avoidance behaviors and anxiety symptoms. Therefore, we should develop a model of ICD patients’ psychological distress including avoidance behaviors, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms. Future research could include the development of psychological care programs focused on avoidance behaviors, as well as longitudinal or randomized controlled studies.

This is the first study to clarify the relationship between avoidance behaviors and depressive symptoms in patients with ICDs, although there were a few methodological limitations. High-quality studies that provide scientific evidence regarding the mechanism for the development of depressive symptoms among patients with ICDs should be conducted in the future.

We are grateful to Yasuyuki Okumura of the Institute for Health Economics and Policy, all Suzuki laboratory members at Waseda University, and the Psychosomatic Medicine Study Group in Cardiology at Tokyo Women's Medical University for supporting our research program. Additionally, we would like to thank all collaborators in the Department of Cardiology at Tokyo Women's Medical University hospitals for their assistance in recruiting participants.