Background/Objective: Training in conflict resolution strategies is a goal in different intervention contexts, and the Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory is a proven, useful tool for assessing these skills. Two studies were conducted, one aimed at analyzing psychometric properties of this instrument, and the other at verifying its ability to discriminate between violent and non-violent adolescent dating partners. Method: In the first study, with 592 adolescents, confirmatory factor analyzes were performed with the two subscales (self and partner). The second study, with 1,938 adolescents, tested whether the factorial structure obtained discriminates between levels of dating violence involvement. Results: Besides verifying the adequacy of items, the results of the first study showed the same three-factor structure in both versions: a positive approach to conflicts and two non-constructive styles, engagement and withdrawal. The second study demonstrated the discriminative capacity of both scales. Conclusions: The final tool, which consisted of 13 items with a good internal consistency, may be useful for assessing the effectiveness of interventions to improve conflict resolution skills, as well as for screening and classification purposes.

Antecedentes/Objetivo: El entrenamiento en resolución de conflictos es objeto de intervención en diferentes contextos, y el Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory ha demostrado su utilidad para evaluar dichas habilidades. Se realizaron dos estudios, uno orientado a analizar las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento, y otro a demostrar su capacidad para discriminar entre parejas de adolescentes violentas y no violentas. Método: En el primer estudio, con 592 adolescentes, se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio con las dos sub-escalas (para sí mismo y para la pareja). El segundo estudio, con 1.938 adolescentes, comprobó si la estructura factorial encontrada discrimina entre niveles de implicación en violencia. Resultados: Además de verificar la adecuación psicométrica de los ítems, los resultados del primer estudio mostraron la misma estructura trifactorial en ambas versiones: una aproximación positiva a los conflictos y dos estilos no constructivos, implicación y retirada. El segundo estudio demostró la capacidad discriminante de ambas escalas. Conclusiones: La versión final del instrumento, con 13 ítems y buena consistencia interna, puede ser útil para evaluar la eficacia de las intervenciones para mejorar la resolución de conflictos y con fines de screening y clasificación.

Romantic relationships during adolescence and emerging adulthood have important implications for development and well-being (van de Bongardt, Yu, Deković, & Meeus, 2015). In addition to helping with the acquisition of specific relational skills, these experiences may influence successive relationships, modifying adolescents’ conceptions. Thus, the way in which adolescents deal with conflicts may lead to various significant health problems (Ha, Overbeek, Cillessen, & Engels, 2012). Overall, satisfactory relationships are characterized by effective strategies of conflict resolution and repair, which favor adequate coping and prevent negative exchanges (Rholes, Kohn, & Simpson, 2014). By contrast, dysfunctional interactions predict poor subjective well-being and increase the likelihood that conflicts will worsen (Siffert & Schwarz, 2011). Defined as interpersonal behaviors used to deal with disagreements, conflict resolution strategies were initially classified into constructive and destructive styles. While the former shows a positive emotional tone and helps to preserve affection, the latter damages the individuals and the relationships due to hostility and disrespect displayed (Flora & Segrin, 2015). Starting from this point, scholars have attempted to describe conflict management styles in more detail.

Kurdek (1994) designed the Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory (CRSI) for assessing the conflict resolution strategies used by both partners. Initially, the scale consisted of four conflict resolution styles: (1) positive, which involves compromise and negotiation; (2) conflict engagement referring to the use of personal attacks and loss of control; (3) withdrawal, which implies refusing to discuss a problematic issue, tuning out the partner; and (4) compliance, which occurs when the person gives in and does not defend his or her own opinion. Subsequently, Kurdek depicted three styles instead of four. Conflict engagement and withdrawal appeared in both, but the third factor varied from compliance (Kurdek, 1995) to positive (Kurdek, 1998). Research on adolescent romantic couples has also shown that constructive, withdrawal and conflict engagement are common strategies to manage their conflicts (Shulman, Tuval-Mashiach, Levran, & Anbar, 2006).

The CRSI has been used across different romantic relationships (opposite and same-sex couples, with or without children), and has proved able to predict changes in couples. For example, the communication pattern in which one partner engages and the other partner withdraws has been related to dissatisfaction and poor subjective well-being (Siffert & Schwarz, 2011). The CRSI has also two versions (CRSI-Self/CRSI-Partner), which makes it possible to evaluate the conflict resolution styles of both partners. Training individuals in conflict resolution strategies is an important goal in different intervention contexts, and is also a common target in programs to prevent teen dating violence (TDV). In this regard, the CRSI has proved to be a useful tool for assessing improvements in these skills (Antle, Sullivan, Dryden, Karam, & Barbee, 2011). In Spain, there are no scales that have been adapted to assess different conflict resolution styles in adolescent dating relationships. Given that dysfunctional early relationships may have numerous negative consequences on health and development (Exner-Cortens, 2014; Fernández-González, O’Leary, & Muñoz-Rivas, 2014), it is essential to have instruments for this purpose. Some questionnaires such as CADRI (Fernández-Fuertes, Fuertes, & Pulido, 2006) or M-CTS (Muñoz-Rivas, Andreu, Graña, O’Leary, & González, 2007) contain a few items that indicate conflict resolution strategies. However, these instruments do not discriminate between different strategies, and some of the items are interpreted as indicators of psychological aggression (e.g., leaving the room annoyed or refusing to discuss the issue). Looking ahead to the intervention, it is important to have measures to distinguish dysfunctional forms of conflict resolution from other more complex types of emotional abuse (Cortés-Ayala et al., 2014; Ureña, Romera, Casas, Viejo, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2015). Moreover, evidence also indicates that Spanish adolescents show some cultural differences in severity of TDV compared with other countries (Viejo, Monks, Sánchez, & Ortega-Ruiz, 2015), which underlines the interest on a Spanish questionnaire adaptation.

A twofold purpose guides the studies described below: first, to adapt the two versions of the CRSI (Kurdek, 1994) in a sample of Spanish adolescents; and second, to verify its ability to discriminate between violent and non-violent adolescent partners.

Study 1In the first study, the psychometric properties of the items and evidence of validity were analyzed through a related construct (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007). Specifically, the relationships between conflict resolution strategies and trait anxiety were examined. As occurs with other facets of neuroticism, higher scores on anxiety have been related to both contending and avoiding as a conflict resolution strategy (Coleman, Deutsch, & Marcus, 2014). Also, research has demonstrated a robust association between anxiety and quality of interaction in adolescent partners (Exner-Cortens, 2014). While teens without emotional problems are more capable of using negotiating tactics that lead to acceptable solutions for both partners (Ha et al., 2012), those who report higher levels of dating anxiety display less positive and more negative interactions in their romantic relationships (La Greca & Mackey, 2007).

MethodParticipantsParticipants were 592 adolescents (47.3% boys and 52.7% girls) aged from 13 to 21 (M=15.67; SD=1.26). All claimed to have or have had at least one dating partner who was of the opposite sex (N=562) or same sex (N=18). Also, nine teens stated they were bi-sexually oriented, and three did not report any sexual orientation. At the time of the study, 44.1% were involved in an intimate relationship. The mean length of their dating relationships was 9.26 months with a median of 5 months (SD=9.86).

Instruments- -

Conflict resolution strategies. The Conflict Resolution Styles Inventory (CRSI; Kurdek, 1994) consists of 16 items, which were initially grouped into four styles: Positive, Conflict engagement, Withdrawal, and Compliance. Participants indicated the frequency of use of these 16 strategies by themselves (CRSI-Self) and their partners (CRSI-Partner). Both subscales ranged from 1 (never) to 5 (always). In the first version of the CRSI, Kurdek (1994) showed good face validity, evidence for construct validity, and evidence for concurrent and predictive criterion-related validity. Also, moderate correlations (from -.20 to .42) were found between conflict resolution styles and dissimilar constructs, like marital satisfaction. Later, Kurdek (1998) used the three-factor version of the CRSI: conflict engagement, positive, and withdrawal. Cronbach's alphas for the composite scores of both partners were between .78 and .87. Other researchers have also found evidence of a good internal consistency of the CRSI in different samples. Ha et al. (2012) found Cronbach's alphas ranged from .77 to .84 in a sample of adolescents.

- -

Anxiety. Anxiety was measured through The Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI; Spielberger, Gorssuch, Lushene, Vagg, & Jacobs, 1983). This self-report subscale consists of 20 items which measure anxiety level as a personal characteristic (α=.79). Participants’ answers to each item ranged from 0 (almost never) to 3 (almost always).

Prior to analyzing the psychometric properties of the CRSI (Self/Partner), a (English-Spanish-English) reverse translation of items and instructions was performed, taking into account cultural and linguistic differences (Muñiz, Elosua, & Hambleton, 2013). Two independent translators, with a good knowledge of both languages, performed the translation from English to Spanish. These two versions were subsequently compared and any discrepancy discussed to reach a consensus on the items. From this set of items, a bilingual translator, unrelated to the previous process, proceeded to translate the scale back from Spanish to English. Finally, the quality of the translation was assessed by comparison with the initial release, while considering possible intercultural differences.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the university to which the authors belong. Also, permission from the families was requested. Participation was voluntary and anonymity was ensured in advance. This instrumental study was carried out using an transversal design (Montero & León, 2007).

Data analysisCFA were performed with LISREL 8.80 (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2006), using weighted least squares. Three models were tested for each of the two subscales, and then compared with each other to see which best fit the data: the four-factor model proposed by Kurdek (1994) and two other three-factor models (Kurdek, 1995, 1998). For these latter models, item loadings were left free to vary on the subscales proposed, and were fixed at zero for the remaining subscales. Goodness of fit of the specified models was evaluated through χ2. Given that virtually any deviation from perfection may produce a statistically significant chi-square with a large sample, three fit indices independent of sample size were also used: (1) the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR, absolute character), where values less than .08 are considered optimal fit, and fit improves as the value approaches .00; (2) the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA, parsimonious character), where values close to .06 are considered optimal fit; and (3) the Comparative Fit Index (CFI, incremental character), where values .95 or higher are indicative of a good fit (Carretero-Dios & Pérez, 2007). The goodness of fit of the models was determined according to the method proposed by Hu and Bentler (1999), who suggested a two-index presentation format. This always includes the SRMR (.08 or lower) with RMSEA (.06 or lower) or with CFI (.95 or higher). To calculate reliability indices and to assess convergent validity, the SPSS v.22 program was used.

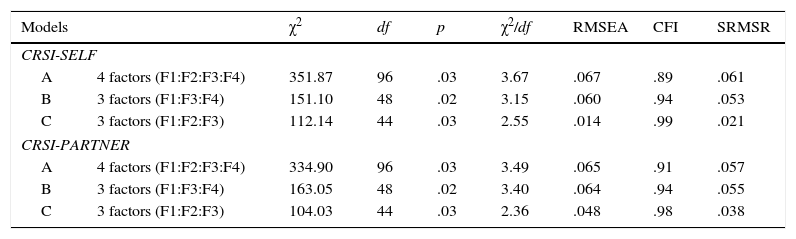

ResultsConfirmatory Factor Analyses, item analysis and reliabilityTo test whether the factor structures proposed by Kurdek were suitable for the data, a CFA was performed for each model and subscale (Table 1). All the models allowed correlation between the three factors.

Goodness of fit indices for each tested model.

| Models | χ2 | df | p | χ2/df | RMSEA | CFI | SRMSR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRSI-SELF | ||||||||

| A | 4 factors (F1:F2:F3:F4) | 351.87 | 96 | .03 | 3.67 | .067 | .89 | .061 |

| B | 3 factors (F1:F3:F4) | 151.10 | 48 | .02 | 3.15 | .060 | .94 | .053 |

| C | 3 factors (F1:F2:F3) | 112.14 | 44 | .03 | 2.55 | .014 | .99 | .021 |

| CRSI-PARTNER | ||||||||

| A | 4 factors (F1:F2:F3:F4) | 334.90 | 96 | .03 | 3.49 | .065 | .91 | .057 |

| B | 3 factors (F1:F3:F4) | 163.05 | 48 | .02 | 3.40 | .064 | .94 | .055 |

| C | 3 factors (F1:F2:F3) | 104.03 | 44 | .03 | 2.36 | .048 | .98 | .038 |

Note. F1: Conflict engagement; F2: Positive; F3: Withdrawal; F4: Compliance

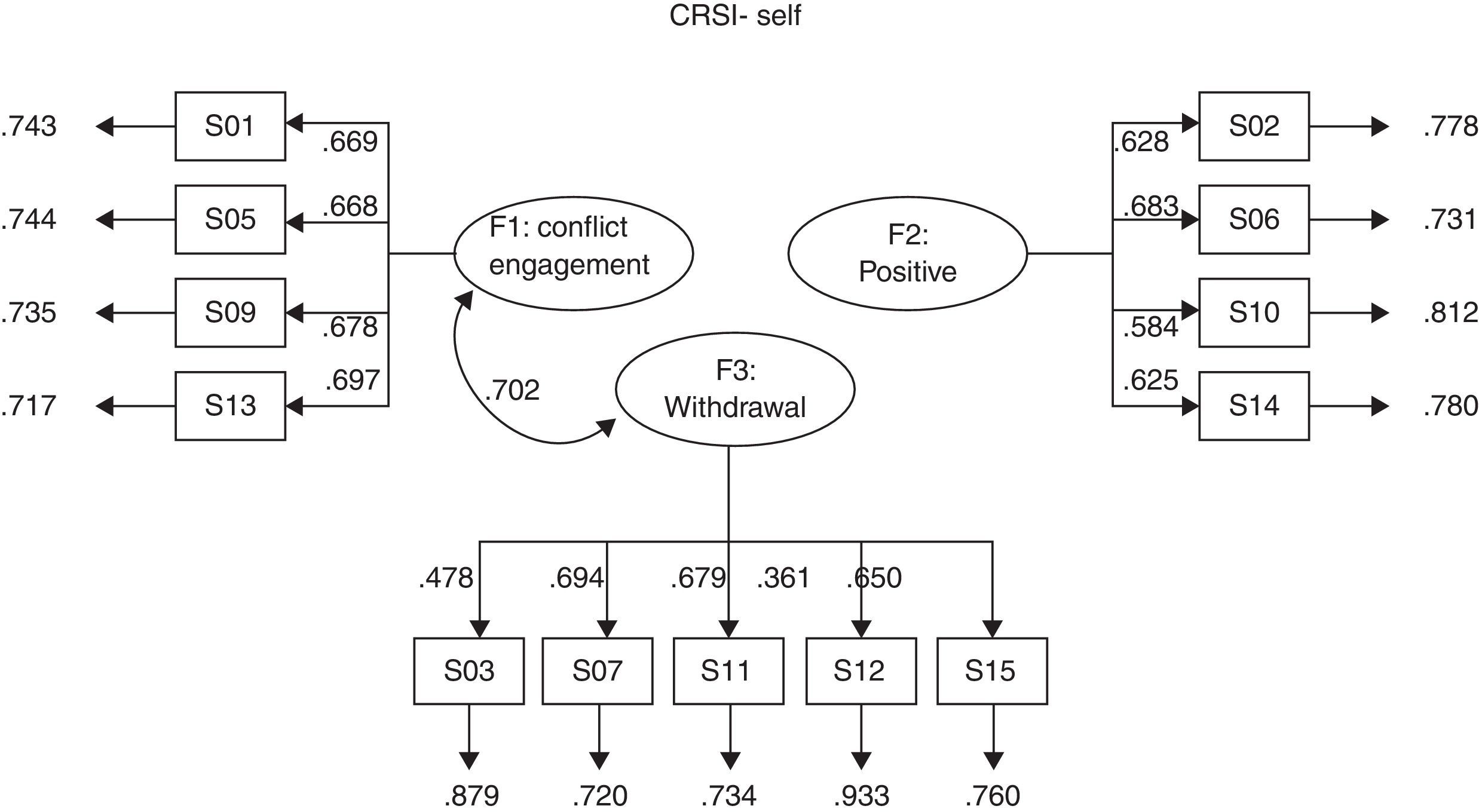

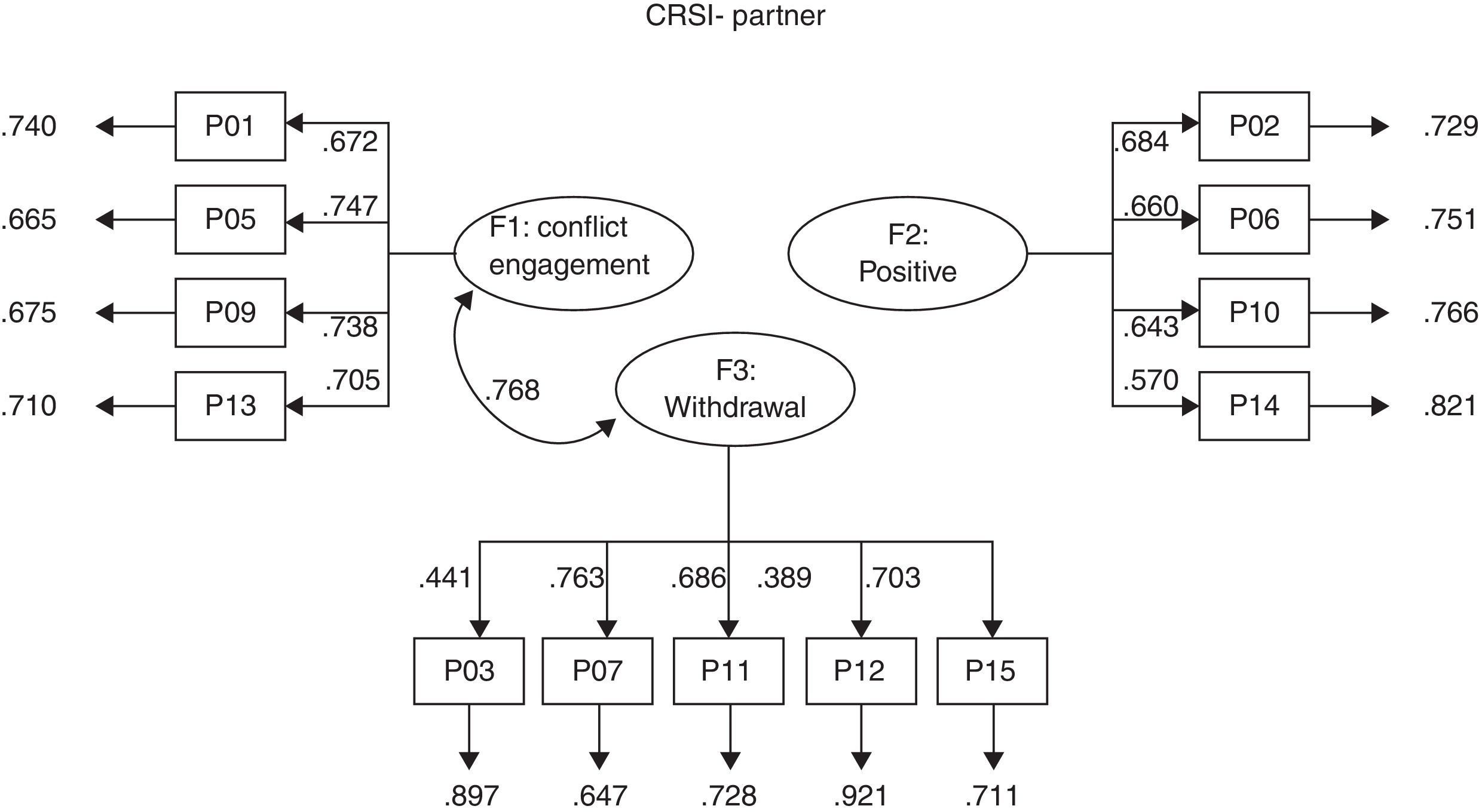

Model A, which represents the original 4-factor model (1994), did not show a good fit because RMSEA>.06 and CFI<.95. Model B, which excludes factor 2 (Positive) of the four original factors (Kurdek, 1995), also yielded inadequate fit values because CFI<.95. Finally, Model C (Kurdek, 1998) excludes factor 4 (Compliance) of the four original factors. By recovering item 12 (which comes from Compliance) for factor 3 (Withdrawal), model C shows the best fit to meet all criteria (SRMR<.08, RMSEA<.06 and CFI>.95). The CFA also showed that all items had loadings on the expected factors over .30, with p values<.001. The best-fitting solution for both subscales (modelC) is a three-factor structure composed of Withdrawal, Conflict engagement, and Positive, adding a new item to the former factor “not defending my position” (Figures 1 and 2).

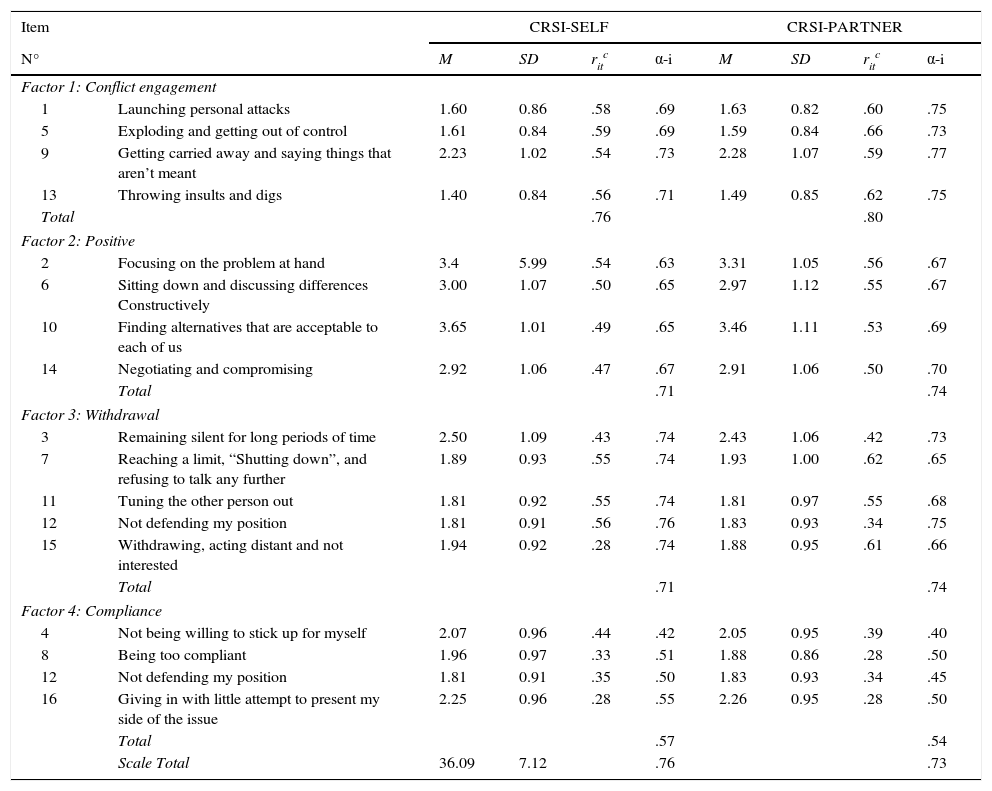

While analyzing the overall internal consistency of both subscales, none of the elements revealed inappropriate behavior (Table 2). The standard deviations are almost 1, so it is possible to assume adequate variability in the ratings. All items show a corrected homogeneity index greater than .30. The subscales exhibited adequate reliability, reaching Cronbach's alphas of .76 (CRSI-Self) and .73 (CRSI-Partner). While no alpha increase would be observed if any item was deleted in the former subscale, two items could be deleted in the latter case.

Mean (M), Standard Deviation (SD), corrected homogeneity index (ritc), and Cronbach's alpha if item is deleted (α-i) of each factor.

| Item | CRSI-SELF | CRSI-PARTNER | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N° | M | SD | ritc | α-i | M | SD | ritc | α-i | |

| Factor 1: Conflict engagement | |||||||||

| 1 | Launching personal attacks | 1.60 | 0.86 | .58 | .69 | 1.63 | 0.82 | .60 | .75 |

| 5 | Exploding and getting out of control | 1.61 | 0.84 | .59 | .69 | 1.59 | 0.84 | .66 | .73 |

| 9 | Getting carried away and saying things that aren’t meant | 2.23 | 1.02 | .54 | .73 | 2.28 | 1.07 | .59 | .77 |

| 13 | Throwing insults and digs | 1.40 | 0.84 | .56 | .71 | 1.49 | 0.85 | .62 | .75 |

| Total | .76 | .80 | |||||||

| Factor 2: Positive | |||||||||

| 2 | Focusing on the problem at hand | 3.4 | 5.99 | .54 | .63 | 3.31 | 1.05 | .56 | .67 |

| 6 | Sitting down and discussing differences Constructively | 3.00 | 1.07 | .50 | .65 | 2.97 | 1.12 | .55 | .67 |

| 10 | Finding alternatives that are acceptable to each of us | 3.65 | 1.01 | .49 | .65 | 3.46 | 1.11 | .53 | .69 |

| 14 | Negotiating and compromising | 2.92 | 1.06 | .47 | .67 | 2.91 | 1.06 | .50 | .70 |

| Total | .71 | .74 | |||||||

| Factor 3: Withdrawal | |||||||||

| 3 | Remaining silent for long periods of time | 2.50 | 1.09 | .43 | .74 | 2.43 | 1.06 | .42 | .73 |

| 7 | Reaching a limit, “Shutting down”, and refusing to talk any further | 1.89 | 0.93 | .55 | .74 | 1.93 | 1.00 | .62 | .65 |

| 11 | Tuning the other person out | 1.81 | 0.92 | .55 | .74 | 1.81 | 0.97 | .55 | .68 |

| 12 | Not defending my position | 1.81 | 0.91 | .56 | .76 | 1.83 | 0.93 | .34 | .75 |

| 15 | Withdrawing, acting distant and not interested | 1.94 | 0.92 | .28 | .74 | 1.88 | 0.95 | .61 | .66 |

| Total | .71 | .74 | |||||||

| Factor 4: Compliance | |||||||||

| 4 | Not being willing to stick up for myself | 2.07 | 0.96 | .44 | .42 | 2.05 | 0.95 | .39 | .40 |

| 8 | Being too compliant | 1.96 | 0.97 | .33 | .51 | 1.88 | 0.86 | .28 | .50 |

| 12 | Not defending my position | 1.81 | 0.91 | .35 | .50 | 1.83 | 0.93 | .34 | .45 |

| 16 | Giving in with little attempt to present my side of the issue | 2.25 | 0.96 | .28 | .55 | 2.26 | 0.95 | .28 | .50 |

| Total | .57 | .54 | |||||||

| Scale Total | 36.09 | 7.12 | .76 | .73 | |||||

The factor scores in each of the two subscales were calculated. Pearson product-moment coefficients were computed for the total score of STAI and for each of the factors. Conflict engagement and Withdrawal factors were correlated significantly with STAI from .16 to .61 (p<.001). The Positive factor was only correlated significantly in the subscale partner (r=.09, p<.05). Additionally, the 33rd and 66th percentiles on the STAI were determined to classify each participant as “low” (those who scored below the 33 percentile), “medium” (between 33 and 66 percentile), or “high” (those who scored higher than the 66 percentile) in trait anxiety. Subsequently, ANOVA were performed to detect significant differences in conflict resolution strategies used by participants with low, medium, and high anxiety.

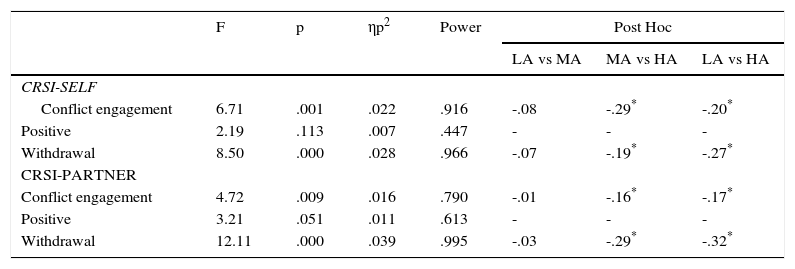

Results were consistent with what was expected, showing the same pattern in both subscales. While high anxiety adolescents showed greater engagement and withdrawal than low and medium anxiety ones, there were no differences regarding positive strategy (Table 3).

ANOVA and post-hoc for factor and anxiety group.

| F | p | ηp2 | Power | Post Hoc | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LA vs MA | MA vs HA | LA vs HA | |||||

| CRSI-SELF | |||||||

| Conflict engagement | 6.71 | .001 | .022 | .916 | -.08 | -.29* | -.20* |

| Positive | 2.19 | .113 | .007 | .447 | - | - | - |

| Withdrawal | 8.50 | .000 | .028 | .966 | -.07 | -.19* | -.27* |

| CRSI-PARTNER | |||||||

| Conflict engagement | 4.72 | .009 | .016 | .790 | -.01 | -.16* | -.17* |

| Positive | 3.21 | .051 | .011 | .613 | - | - | - |

| Withdrawal | 12.11 | .000 | .039 | .995 | -.03 | -.29* | -.32* |

Note. df: 2,589; LA: low-anxiety group; MA: medium-anxiety group; HA: high-anxiety group

Research interested in TDV has increased over the last decades in Spain, indicating a high prevalence and negative correlates (Cortés-Ayala et al., 2014; Fernández-González et al., 2014; Gonzalez-Mendez, Yanes, & Ramírez-Santana, 2015). TDV is often characterized by be moderate and bidirectional (Viejo et al., 2015), which suggests that most of cases do not follow a gender violence pattern. However, little attention has been paid to relationship communication compared to other processes (Messinger, Rickert, Fry, Lessel, & Davidson, 2012). This has meant putting the focus on aggressive tactics and failing to analyze conflict resolution styles that predict escalation to aggression, despite young people in violent relationships use both escalating strategies and temporary avoidance more frequently than those in nonviolent relationships (Bonache, Gonzalez-Mendez, & Krahé, in press; Messinger et al., 2012).

Moreover, effective prevention programs in different areas are oriented towards strengthening positive skills and not only reducing risks (American Psychological Association, 2013). Thus, having instruments to measure conflict resolution strategies is critical to assess relational dynamics from a preventive point of view. Immaturity and poor skills favor high prevalence of aggression in adolescent couples, and it also explains desistence detected in most cases (Orpinas, Hsieh, Song, Holland, & Nahapetyan, 2013). In this sense, treating TDV exclusively as a problem of gender inequality may be a limited contribution to preventing the problem, as long as teens are not provided with adequate tools to do things right. According to these ideas, the ability of the CRSI to discriminate between violent and non-violent dating partners was tested.

MethodParticipantsIn this second study, participants were 1,938 adolescents (942 boys and 996 girls), with ages ranging from 13 to 18 (M=15.50; SD=1.12). All claimed to have or have had at least one dating partner (38.4% were involved in a romantic relationship at the time of the study). Regarding their sexual orientation, 95.1% indicated a preference for opposite-sex partners, 1.8% same-sex partners, 2.8% partners of both sexes and 0.3% did not report any sexual orientation. The dating relationships had lasted an average of 9.46 months (SD=9.81) with a median of 5 months.

InstrumentsDating violence victimization/perpetration. A subscale developed by Safe Dates-Psychological Abuse Victimization (Foshee et al., 1998) was used for assessing both psychological abuse victimization and perpetration. This subscale consists of 14 items that measure: verbal aggression (said things to hurt my feelings on purpose, brought up something from the past to hurt me, etc.), control of the intimate partner (told me I could not talk to someone of the opposite sex, etc.), and interrupted physical aggression (threw something at me but missed, etc.). In addition, three items from a shortened version of the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS; Straus & Douglas, 2004) were used to measure physical aggression (pushing, hitting, and causing injury). All responses ranged from 0 (never) to 3 (very often). Cronbach's alpha reached .87 for victimization and .83 for perpetration.

ProcedureThe study was approved by the ethics committee of the university to which the authors belong. Also, prior authorization was requested from educational centers and families. All students responded to the same questionnaire, and all received identical instructions. The data set was collected in the classrooms, with participation being voluntary. However, the data from participants who had never had a dating relationship were later excluded from the analysis.

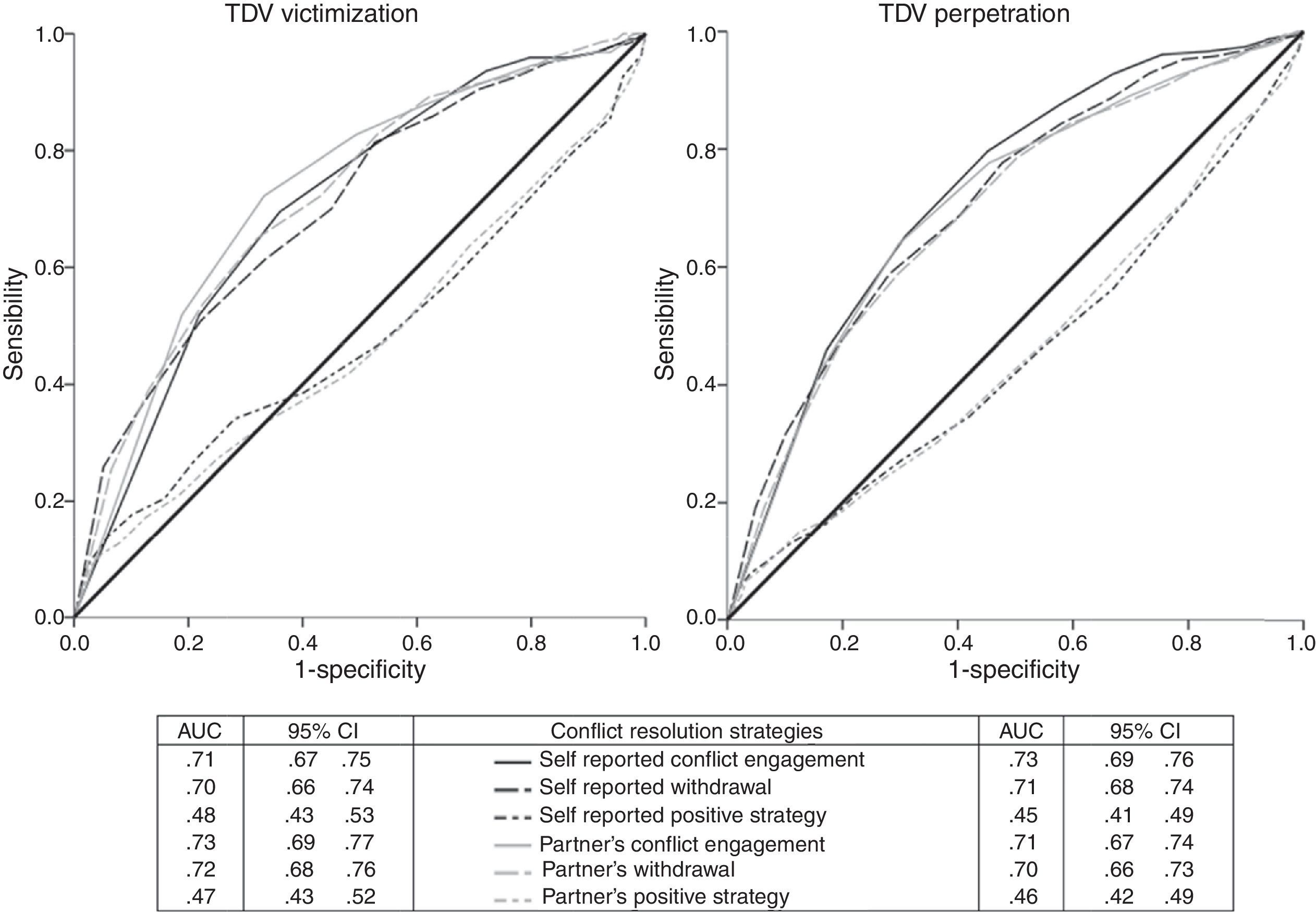

ResultsFirst, the 33rd and 66th percentile composite scores on TDV perpetration and victimization were determined separately. Then, participants were classified as “low” (those who scored below the 33rd percentile) or “high” (those who scored above the 66th percentile) in each measure and selected for further analyses. Also, the different conflict resolution strategies measured through CRSI-Self and CRSI-Partner were used. Subsequently, ROC curves were generated, confirming that the strategies withdrawal and conflict engagement show great discriminatory power, while the positive resolution strategy shows no ability to discriminate, neither victimization nor perpetration (Figure 3). Discrimination between high and low perpetrators showed a sensitivity of 88.0% and a specificity of 65.3% with an accuracy of 75.7%. In victimization case, it had a sensitivity of 82.3% and a specificity of 75.3% with an accuracy of 78.6%.

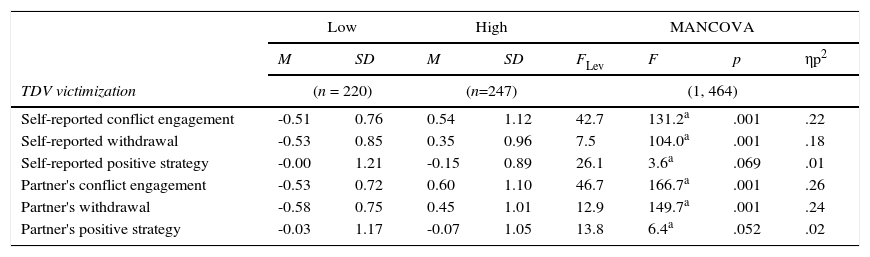

Finally, a multivariate analysis was computed using participants’ age as a covariate to verify these results. Multivariate contrasts showed significant differences according to both the level of victimization (F(6, 459)=37.39, p < .001, μp2=.33) and the level of perpetration (F(6, 627)=39.02, p<.001, μp2 = .27). As shown in Table 4, significant between-subject effects were detected for both TDV perpetration and victimization. Those who scored higher in victimization or perpetration reported conflict engagement and withdrawal, both by their partners and themselves, more often than those who scored lower. Moreover, no significant differences were detected regarding positive strategy.

Comparison between conflict resolution strategies reported by participants high or low in TDV perpetration and victimization.

| Low | High | MANCOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | FLev | F | p | ηp2 | |

| TDV victimization | (n = 220) | (n=247) | (1, 464) | |||||

| Self-reported conflict engagement | -0.51 | 0.76 | 0.54 | 1.12 | 42.7 | 131.2a | .001 | .22 |

| Self-reported withdrawal | -0.53 | 0.85 | 0.35 | 0.96 | 7.5 | 104.0a | .001 | .18 |

| Self-reported positive strategy | -0.00 | 1.21 | -0.15 | 0.89 | 26.1 | 3.6a | .069 | .01 |

| Partner's conflict engagement | -0.53 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 1.10 | 46.7 | 166.7a | .001 | .26 |

| Partner's withdrawal | -0.58 | 0.75 | 0.45 | 1.01 | 12.9 | 149.7a | .001 | .24 |

| Partner's positive strategy | -0.03 | 1.17 | -0.07 | 1.05 | 13.8 | 6.4a | .052 | .02 |

| Low | High | MANCOVA | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | FLev | F | p | ηp2 | |

| TDV perpetration | (N = 382) | (N=253) | (1, 632) | |||||

| Self-reported conflict engagement | -0.47 | 0.72 | 0.60 | 1.19 | 79.42 | 195.7a | .001 | .24 |

| Self-reported withdrawal | -0.46 | 0.83 | 0.39 | 1.02 | 19.89 | 128.2a | .001 | .17 |

| Self-reported positive strategy | 0.09 | 1.10 | -0.04 | 0.93 | 6.98 | 3.7a | .064 | .01 |

| Partner's conflict engagement | -0.42 | 0.76 | 0.44 | 1.11 | 48.49 | 131.5a | .001 | .17 |

| Partner's withdrawal | -0.44 | 0.85 | 0.36 | 1.04 | 14.06 | 109.6a | .001 | .15 |

| Partner's positive strategy | 0.09 | 1.09 | -0.02 | 0.97 | 2.91 | 2.4 | .121 | .01 |

Note. FLev: Levene's test

The first study was aimed at adapting the CRSI (Kurdek, 1994) in a sample of Spanish adolescents. The analysis of the 16 items showed adequate psychometric properties in its two versions (Self/Partner). Given that the structure of the CRSI has changed in successive studies (Kurdek, 1994, 1995, 1998), the different dimensional possibilities were examined. CFAs were performed with the two subscales separately, and then compared to each other. The Spanish adolescent final version of the CRSI shows a common dimensional structure for both subscales, composed of three factors with 13 items in total. It is shorter than the original because some items have been removed to ensure consistency and homogeneity of the factors (Appendix). The dimensions detected are Positive, Conflict engagement, and Withdrawal. While the former two have the original composition, a fifth item, originally from Compliance, had to be added to Withdrawal (“not defending my position”). This three-dimensional structure partially replicates that depicted by Kurdek (1998) and finds support in other studies as discussed below. Compliance has been elusive for researchers, showing low reliability. Therefore, its absence in this study is consistent with previous evidence. In fact, it may not be easy to observe in the partner because it may be confused with avoidance or withdrawal (Zacchilli, Hendrick, & Hendrick, 2009), which might explain the transfer of an item from compliance to withdrawal. Although Kurdek was unable to replicate the positive strategy after his first study, the current confirmatory factor analysis preserves this strategy without changing the valence of any item. Keeping this positive style is interesting for prevention because it facilitates the evaluation of strengths.

By contrast, conflict engagement and withdrawal have emerged as distinct styles through the CRSI and other instruments. These styles correspond with the demand/withdraw pattern, which has been consistently linked to low satisfaction in relationships (Flora & Segrin, 2015). In this pattern, while one partner attempts to discuss conflictive issues and demands changes, the other partner withdraws, through silence, defensiveness, or refusal to discuss the issue. Conflict engagement and withdrawal are used by both genders, depending on who generates the conflict topic (Christensen, Eldridge, Catta-Preta, Lim, & Santagata, 2006). Finally, it is worth mentioning that the three conflict resolution styles detected in this study have also been found using this instrument by other researchers (Kosic, Noor, & Mannetti, 2012).

Evidence of construct validity was obtained by confirming that the CRSI (Self/Partner) discriminates between the high-anxiety group and the other two groups (medium and low anxiety) in both dysfunctional conflict resolution strategies. Specifically, the more anxious the teens are, the more likely they are to use conflict engagement and withdrawal. These results are consistent with previous research indicating that highly anxious teens are more likely to inadequately address conflicts than those who score low in anxiety (Exner-Cortens, 2014; Ha et al., 2012).

As noted in the introduction, early romantic experiences have implications for development and well-being (van de Bongardt et al., 2015), and dysfunctional dynamics may adversely affect health, academic achievement, and even future income (Exner-Cortens, 2014). This makes it necessary to have instruments capable of evaluating conflict resolution styles in adolescent partners. By analyzing its psychometric properties, the Spanish version of the CRSI has showed it can be a useful tool in both research and intervention with adolescents.

The purpose of the second study was to test the ability of the CRSI to discriminate between violent and non-violent dating partners. In this sense, the results confirmed that adolescents classified as high or low in TDV victimization/perpetration differ significantly in the destructive strategies reported. Thus, highly victimized teens reported higher engagement and withdrawal by their partners and themselves than the less victimized. In addition, those high in perpetration also reported higher engagement and withdrawal by their partners and themselves than those low in perpetration. These results clearly show that the two subscales of the CRSI make it possible to distinguish between the strategies of those who have been involved in violence and those who have not. By contrast, no differences were found in the use of positive problem solving. This latter result is consistent with evidence indicating that violent dating relationships do not differ in levels of love, intimate self-disclosure, or perceived partner caring (Giordano, Soto, Manning, & Longmore, 2010; Viejo et al., 2015).

Emotional and physical abuse is highly prevalent in adolescent population and it is associated with important consequences on health and development (Fernández-González et al., 2014; Vagi, Olsen, Basile, & Vivolo-Kantor, 2015). However, while it is claimed that interventions should be geared towards strengthening resilience (Grych, Hamby, & Banyard, 2015), underlying processes of TDV, such as communication patterns, have received peripheral attention. In this sense, conflict resolution strategies are an adequate target, since they may increase the individual's capacity to both manage negative affect and maintain positive affect. This Spanish version of the CRSI may be useful as a tool for evaluating the effectiveness of this type of intervention, as well as for screening and classification purposes. Specifically, it may help detect those teens at high risk of becoming involved in dating violence.

The study's results should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. Despite having detected a clear three-factor structure in adolescents, this structure is not directly transferable to other populations. In addition, although this three-factor structure has been found in relationships with parents and friends (Kosic et al., 2012), further research is required to confirm whether it is applicable to other types of relationship. Moreover, the usefulness of the instrument to predict different consequences arising from dysfunctional dating relationships should be tested through longitudinal designs.

FundingThis research was funded in part by the Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad (Spain) and European Social Fund under Grant 53/12.

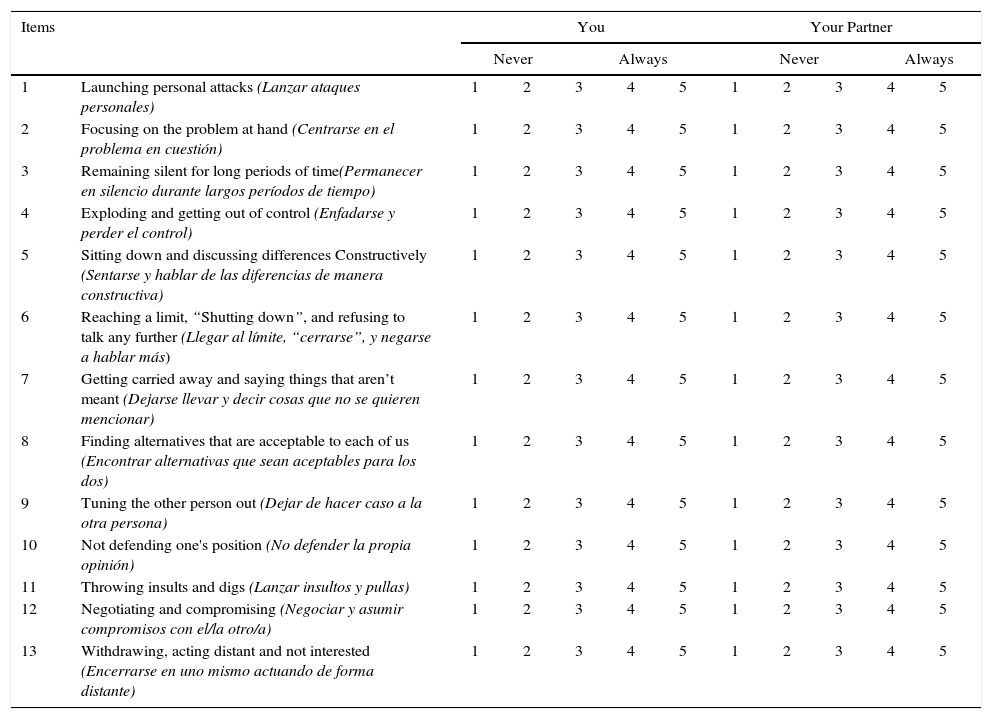

Instructions: From 1= Never to 5=Always, indicate how often YOU or YOUR PARTNER use the following strategies to deal with the arguments or disagreements.

| Items | You | Your Partner | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never | Always | Never | Always | ||||||||

| 1 | Launching personal attacks (Lanzar ataques personales) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2 | Focusing on the problem at hand (Centrarse en el problema en cuestión) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3 | Remaining silent for long periods of time(Permanecer en silencio durante largos períodos de tiempo) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4 | Exploding and getting out of control (Enfadarse y perder el control) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5 | Sitting down and discussing differences Constructively (Sentarse y hablar de las diferencias de manera constructiva) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6 | Reaching a limit, “Shutting down”, and refusing to talk any further (Llegar al límite, “cerrarse”, y negarse a hablar más) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7 | Getting carried away and saying things that aren’t meant (Dejarse llevar y decir cosas que no se quieren mencionar) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8 | Finding alternatives that are acceptable to each of us (Encontrar alternativas que sean aceptables para los dos) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9 | Tuning the other person out (Dejar de hacer caso a la otra persona) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10 | Not defending one's position (No defender la propia opinión) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11 | Throwing insults and digs (Lanzar insultos y pullas) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12 | Negotiating and compromising (Negociar y asumir compromisos con el/la otro/a) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13 | Withdrawing, acting distant and not interested (Encerrarse en uno mismo actuando de forma distante) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

Items for each factor: Conflict Engagement: 1, 4, 7, and 11; Positive: 2, 5, 8, and 12; Withdrawal: 3, 6, 9, 10, and 13.