Although there is broad agreement that perceived risks determine risk-taking behavior, previous research has shown that this association may not be as straightforward as expected. The main objective of this study was to investigate if the levels of impulsivity can explain part of these controversial findings.

MethodA total of 1579 participants (Mage = 23.06, from 18 to 60 years; 69.4% women) were assessed for levels of risk perception, risk-taking avoidance, and impulsivity.

ResultsThe results showed that while impulsivity was significantly and negatively related to both risk perception and risk-taking avoidance, the relationship with risk-taking avoidance was significantly stronger than with risk perception. The levels of impulsivity predicted risk-taking avoidance even when controlling for risk perception.

ConclusionsThese findings indicate that impulsivity can differentially affect risk perception and risk-taking. We propose that the stronger influence of impulsivity on risk-taking is due to the greater reliance of risk-taking, compared with risk perception, on automatic processes guided by impulses and emotions.

In the literature on risk, it is well accepted that risk-taking behavior is largely determined by perceived risk (Brewer et al. 2007; Sheeran, 2014; Weber et al., 2002; Weller & Tikir, 2011). In general, there is agreement that higher levels of perceived risk are related to a lower tendency to engage in risky behavior. However, it is not difficult to recall instances where our decisions were not made in accordance with the perceived risk.

Sometimes people may engage in risks due to a lack of experience or information about the context where their behavior is performed. In these cases, people may not have a clear perception of the risk or could misunderstand the consequences that their decision entails. Nevertheless, research has revealed that often risk behaviors are undertaken knowing the risks and being aware that these actions may lead to severe negative consequences (see Reyna and Farley (2006) for a review of the topic). For example, it has been observed that daily smokers perceive a higher likelihood of getting lung cancer than non-smokers or that adolescents engaging in unprotected sex perceive a higher risk of being infected with a sexually transmitted disease (Johnson et al., 2002; Sneed et al., 2001). Likewise, drivers are aware that risky behaviors are one of the main causes of road fatalities, and yet these behaviors continue to underlie the number of fines and accidents recorded (Cestac, & Delhomme, 2012; Dénommée et al., 2020; IRTAD, 2020). Moreover, in the literature on risk behavior, it is even possible to find studies reporting positive correlations between perceived risk and the decision to take risks (Mills et al. 2008; Reyna & Farley, 2006; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). Thus, the relationship between risk perception and risk-taking seems to be somewhat less straightforward than first expected.

Along with risk perception, previous research has demonstrated that numerous variables can account for the variance in risk-taking behavior such as the perceived benefits of our actions, sensitivity to reward, risk propensity, feelings of invulnerability, social context, emotional states, memory cues, or levels of impulsivity (Baltruschat et al., 2021; Bohm & Harris, 2010; Gerrard et al., 1996; Megías et al., 2011; Megías et al., 2014; Mills et al., 2008; Reniers et al., 2016; Reyna & Farley, 2006; Sánchez-López et al., 2022; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992; Yates, 1992). Among the mentioned factors, impulsivity has been the one most closely linked to risk behavior (Chamorro, 2012; Reniers et al., 2016; Stevens, 2017; Zuckerman & Kuhlman, 2000). Higher levels of impulsivity are associated with risk-taking behaviors such as substance abuse (Perry & Carroll, 2008; Torres et al., 2013), gambling (Cyders & Smith, 2008; Navas et al., 2017), risky driving (Baltruschat et al., 2020; Navas et al., 2019), or risky sexual behaviors (Deckman & DeWall, 2011; Dir et al., 2014).

The previous literature has shown that impulsivity influences both the process of risk perception and risk-taking (Lozano et al, 2017; Reniers et al., 2016). However, as we will see below, we proposed that impulsivity could differentially impact risk perception and risk-taking given the contextual differences that usually characterize both tasks (Megías et al., 2015). For example, decisions in risk contexts are often accompanied by intense emotional states and time pressure. In such circumstances, a deliberative analysis of the situation can be difficult and too demanding, requiring excessive time to process the information. Thus, our actions are usually guided by more automatic processes when taking risks, characterized by fast responses and a greater influence of impulses, emotions, and stimulus-response associations learned by previous experience. Conversely, when we ask people to rate the level of risk perceived in a situation, they rely on a more rational and controlled cost-benefit analysis of the situation given that responses are not so imperative — these do not involve immediate negative consequences — which leads to a lower influence of impulsive mechanisms (Megías et al. 2011, 2015; Maldonado et al., 2020).

AimsThe primary aim of the present study was to investigate whether individuals' levels of impulsivity can help to explain the differences observed between risk perception and risk-taking. To this end, a sample of 1579 participants were assessed for levels of risk perception and risk-taking through the DOSPERT scale, and levels of impulsivity through the UPPS-P impulsive behavior scale. We pursued our objective by testing two hypotheses. First, we hypothesize that impulsivity is related to both risk perception and risk-taking, although impulsivity will have a greater influence on risk-taking given its stronger reliance on automatic processes guided by impulses and emotions. In the case of risk perception, the more deliberate assessment of the situation would weaken the influence of impulsive mechanisms. Second, given the expected relationship between impulsivity and the variables of risk perception and risk-taking, we were interested in testing the predictive value of impulsivity and risk perception for risk-taking-avoidance. We hypothesize that levels of impulsivity are related to risk-taking avoidance even when controlling for levels of risk perception.

MethodParticipantsOne thousand five hundred seventy-nine volunteer participants took part in this study. A total of 69.4% of the sample were women. The mean age was 23.06 years (SD = 6.26), ranging from 18 to 60. The participants were recruited via advertisements at the Campus of the University of Granada and via social networks related to this university.

Before joining the study, participants were informed of the confidentiality and anonymity of the collected data and all of them signed an informed consent form. They were always treated in accordance with the Helsinki declaration (World Medical Association, 2008). The Research Ethics Committee of the University of Málaga approved the study protocols (approval number: 10-2019-H) as part of the research project UMA18-FEDERJA-13.

Procedure and instrumentsParticipants were assessed on impulsivity and risk behavior (risk perception and risk-taking) by the UPPS-P and DOSPERT scales. This assessment was part of a larger project aimed to investigate the factors underlying risk behavior. The scales were available online through the Limesurvey platform (http://limesurvey.org). Access was provided via email invitation from the authors. Details of each of the scales are described below.

The UPPS-P Short Version (Cándido et al. 2012; Cyders, & Smith, 2007) is a 20-item self-report scale used for the assessment of impulsivity. Participants are asked to indicate their level of agreement with the statements of each item on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“I strongly agree”) to 4 (“I strongly disagree”). The scale covers five subdimensions of impulsivity: positive urgency (e.g., ‘‘I tend to lose control when I am in a great mood’’), negative urgency (e.g., ‘‘When I am upset I often act without thinking’’), (lack of) premeditation (e.g., ‘‘My thinking is usually careful and purposeful’’), (lack of) perseverance (e.g., ‘‘Once I get going on something I hate to stop’’), and sensation seeking (e.g., ‘‘I quite enjoy taking risks’’). In the present study we worked with the total score of the scale. The internal consistency of the total score in our sample was α = .83.

The DOSPERT (Lozano et al., 2017; Weber et al., 2002) is a self-report scale that assesses risk behavior in various domains of everyday life (ethical, financial, health/ security, recreational, and social) through three different aspects: risk-taking, risk perception, and expected benefits. Each one of these aspects is assessed by a 40-item subscale with a 7-point Likert format. All the items are common across the three subscales, but the subscales differ in the type of response required. In our study we used the total score of the subscales of risk-taking and risk perception. In the risk-taking subscale the individuals are asked to assess how likely they would be to engage in a particular behavior (ranging from 1 [extremely unlikely] to 7 [extremely likely]) and in the risk perception scale they are asked to rate how risky they consider the behavior (from 1 [not at all risky] to 7 [extremely risky]). The internal consistency of the total score in our sample was α = .85 for the risk-taking subscale and α = .86 for the risk perception subscale.

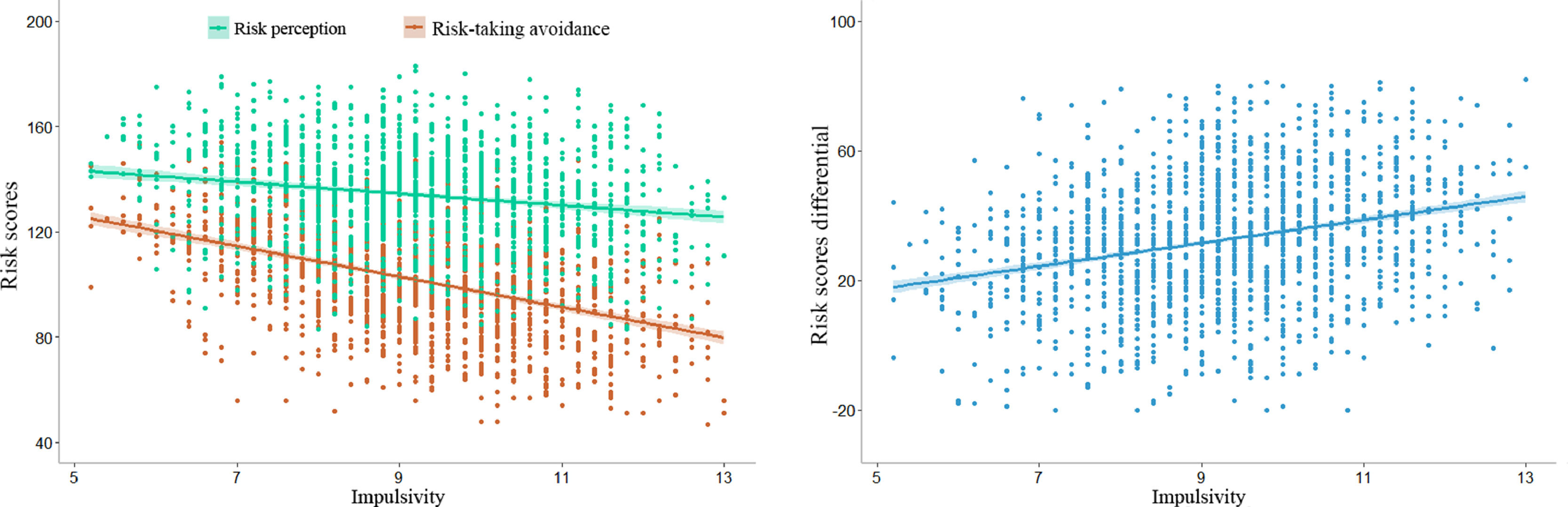

Statistical analysesWe computed two new measures from the original scores of the DOSPERT scale: The scores of the risk-taking subscale were reversed (hereinafter referred to as risk-taking avoidance). This change allows the subscales of risk-taking and risk perception to follow the same direction, so that the higher the scores, the higher the perceived risk and the higher the risk avoidance. We also computed a second new variable by subtracting risk-taking avoidance from risk perception (risk perception – risk-taking avoidance; hereinafter referred to as risk scores differential). This variable was computed only with the aim of facilitating a better graphical interpretation of the differences between risk perception and risk-taking avoidance as a function of impulsivity. This variable was not included in the analysis, given the methodological problems associated with the use of difference scores (Edwards, 1994; Laird, 2020).

Descriptive statistics were first calculated for the variables included in the study (impulsivity, risk perception, and risk-taking avoidance). Moreover, gender differences and age effects on these variables were examined using t-test and Pearson's correlation coefficient, respectively. Second, we studied the relationship between study variables by Pearson's correlation coefficient. Possible interaction effects of gender and age on these relationships were also examined by conducting multiple regression analysis. Third, we were interested in analysing if there were differences in the strength of the relationship between impulsivity and the variables of risk perception and risk-taking avoidance. To this end, Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z test was conducted to compare both correlations (Meng et al., 1992). Finally, a multiple regression analysis was conducted to study in more depth the relationship between risk-taking avoidance, risk perception and impulsivity. Risk-taking avoidance was entered as criterion and risk perception, impulsivity, gender, age, and the interaction term between risk perception and impulsivity were entered as predictors. Descriptive statistics, t-tests, Pearson's correlations and regressions were performed using SPSS version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk NY, USA) and Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z test was conducted using Cocor package in R (Diedenhofen & Musch, 2015).

ResultsDescriptive statistics (for the total sample and separately for gender) and Pearson's correlations for each of the variables under study are shown in Table 1. Analysis of gender differences (independent t-tests) revealed that women, compared with men, perceived higher levels of risk (t(1577) = 5.67, p < .001, d = 0.31) and avoided making risk decisions with a higher probability (t(1577) = 6.15, p < .001, d = 0.33). The remaining variables did not show any gender differences. Age correlated positively with risk perception (r = 0.07, p < .01) and risk-taking avoidance (r = 0.15, p < .001), and negatively with impulsivity (r = -0.18, p < .001).

Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for the total sample and divided by gender) and Pearson's correlation matrix of the studied variables.

Pearson's correlation analyses for the variables of interest revealed that impulsivity was negatively correlated with risk perception (r = -0.18, p < .001) and risk-taking avoidance (r = -0.44, p < .001; see Table 1 and Fig. 1). Moreover, a positive relationship was observed between risk perception and risk-taking avoidance (r = 0.49, p < .001; see Table 1). This pattern of relationships was similar for both genders and through age (interaction effects: all p > .05).

Left panel: Relationship between impulsivity and the variables of risk perception and risk-taking avoidance. Right panel: Visual representation of the relationship between impulsivity and risk scores differential (i.e., risk perception – risk-taking avoidance). The shaded area around each regression line indicates the 95% confidence interval.

The statistical comparison of the correlations between impulsivity and the subscales of risk perception and risk-taking avoidance using Meng, Rosenthal, and Rubin's z test revealed a significant stronger negative relationship between impulsivity and risk-taking avoidance than between impulsivity and risk perception (Z = 10.92, p < .001). These differences can be better visualized in Fig. 1.

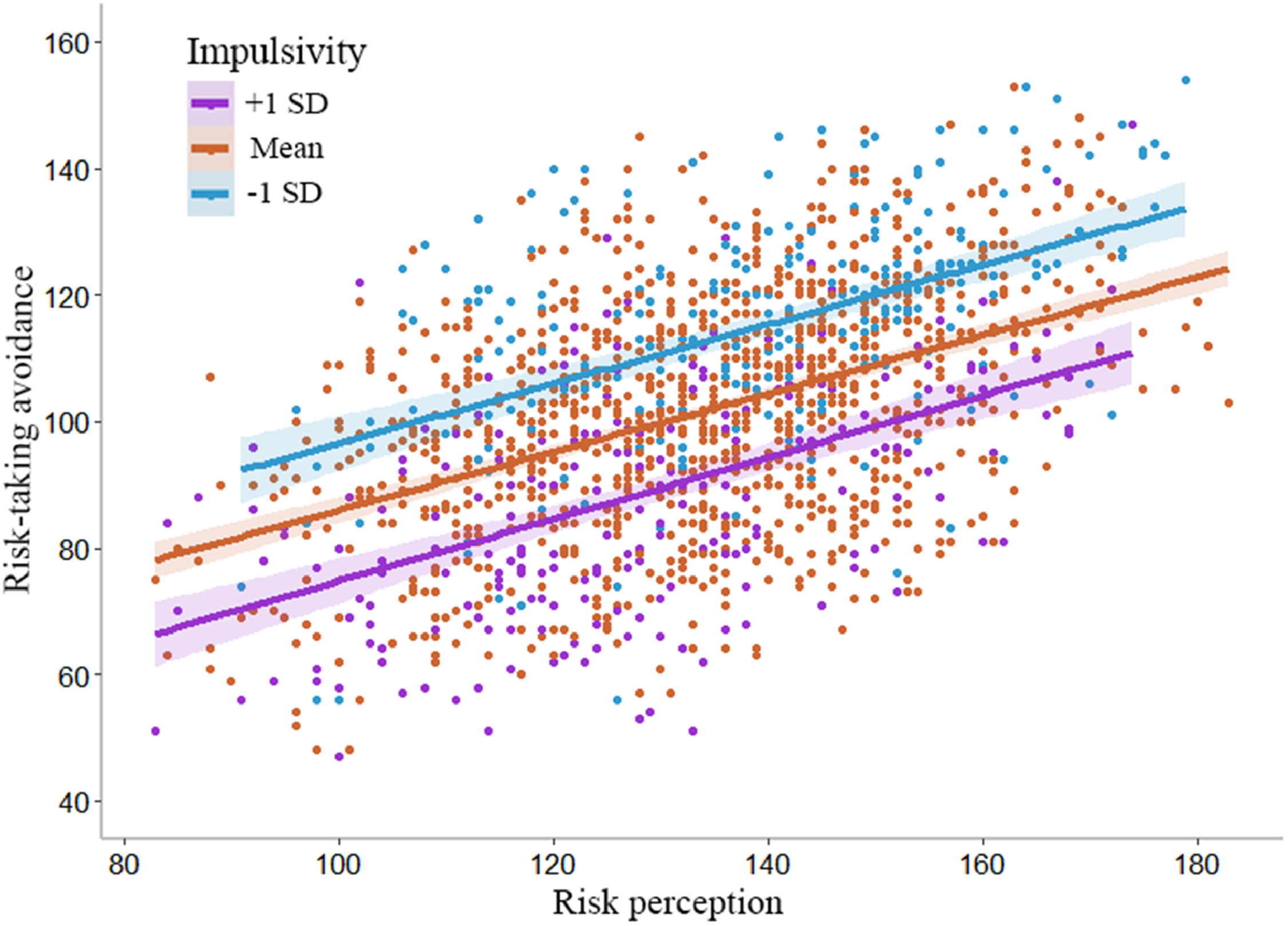

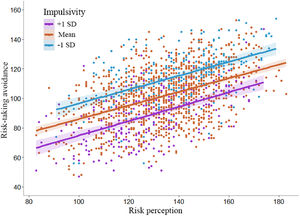

Finally, as shown in Table 2, the results of the multiple regression analysis revealed that risk-taking avoidance was predicted by risk perception (β = .40, p < .001), impulsivity (β = -.36, p < .01), gender (β = .09, p < .001), and age (β = .06, p < .01). The interaction term between risk perception and impulsivity showed no significant relationship with risk-taking avoidance (p < .05). See Fig. 2 for a visual representation of the most relevant results.

Results for the multiple regression model predicting risk-taking avoidance.

R2 = 0.38, p < 0.001

Relationship between risk perception and risk-taking avoidance as a function of the levels of impulsivity. For graphical representation, values for impulsivity have been discretized into three categories: 1 SD below the mean, mean, 1 SD above the mean. The shaded area around regression lines indicates the 95% confidence interval.

There is a broad consensus that risk perception is a protective factor for risk-taking (Reniers et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2002). However, people often engage in risk-taking behaviors even when their risk perception is accurate and when they are aware of the possible negative consequences of their actions. The previous literature has tried to address these inconsistencies from several perspectives such as differences in risk propensity or in the type of cues retrieved from memory (Mills et al., 2008; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). The current study aimed to investigate if the levels of impulsivity can explain part of the contradictory findings concerning the relationship between risk perception and risk-taking.

Three are the main findings of the present research: a) we observed a significant negative relationship between impulsivity and the variables of risk perception and risk-taking avoidance. That is, higher levels of impulsivity were associated with a lower tendency to perceive risks and less avoidance of these risks; b) interestingly, the relationship with impulsivity was significantly stronger for risk-taking avoidance than for risk perception. This led to an increased difference between the risk perception and risk-taking avoidance scores in those individuals with higher levels of impulsivity; c) both risk perception and impulsivity independently predicted the scores on risk-taking avoidance, but there was no interaction between these two factors.

Taken together, these findings suggest that impulsivity could be one of the factors that might explain the individual differences between the reported perceived risk and the risk behavior eventually executed. Focusing on the first hypothesis of this study, our results support those of the previous literature showing that greater impulsivity leads to a stronger tendency towards risk (Chamorro, 2012; Reniers et al., 2016), which, in our case, was reflected in both lower risk perception and lower avoidance of risk-taking. Likewise, the present study also provided new evidence to better understand this relationship. According with our hypothesis, we observed that the levels of impulsivity were more strongly associated with risk-taking than with risk perception. Thus, those participants with higher levels of impulsivity showed a more pronounced difference between the risk perception and risk-taking avoidance scores, revealing a higher tendency to take risks even though the perception of risk does not increase proportionally.

The stronger influence of impulsivity on the process of risk-taking, compared with risk perception, could be explained by the higher reliance of risk-taking on automatic processes (Megías et al. 2011, 2015; Maldonado et al., 2020). As already mentioned in the Introduction section, risk-taking behavior is usually carried out in contexts characterized by intense emotions and time pressure. These features create the appropriate conditions for behavior to be guided by impulses and automatic stimulus–response associations, thus allowing for faster responses to risk than a deliberative reasoning (Megías et al., 2015). However, in the case of risk perception, when people are asked to estimate the perceived risk in a particular situation, the response can be less rushed and rely on a more rational cost-benefit analysis, which is less susceptible to the impact of impulsivity.

With respect to our second hypothesis, our results are in accord with the literature supporting the idea that the level of perceived risk determines risk-taking (Reniers et al., 2016; Weber et al., 2002). In addition, the levels of impulsivity also predicted risk-taking, even when controlling for the variance shared with risk perception (and there was no interaction between risk perception and impulsivity). Risk perception and impulsivity were independent predictors of risk-taking. As impulsivity increases, risk-taking avoidance decreases regardless of the perceived risk. Thus, two people who perceive similar risks can behave differently depending on their level of impulsivity.

To further integrate these findings into the current models of risk decision-making, it will be necessary to address some limitations of the present study. First, future research should employ experimental methodology to explore the possible causal relationships among the studied variables, thus overcoming the limitations of correlational methodology. Second, the literature has shown several additional individual and contextual factors that influence risk behavior, such as risk propensity, sensitivity to reward, emotional states, or social pressure (Baltruschat et al., 2021; Megías et al., 2011; Reniers et al., 2016; Sitkin & Pablo, 1992). These factors should be considered to clarify how risk perception is related to risk-taking and to better specify the role of impulsivity in this relationship. Finally, it would be interesting to investigate risk behavior in more realistic environments, using, for example, computerized tasks, simulation systems, or virtual reality that allow us to evaluate the participants' performance in risky contexts rather than a self-reported perception of their risk-taking tendency.

ConclusionThe findings of this study can contribute towards a better understanding of the mechanisms involved in risk perception and risk-taking behavior. Our study suggests that impulsivity can differentially affect these two processes and could thus (at least partially) explain the inconsistent results found in the previous literature about how risk perception is related to risk-taking. We anticipate that these findings could help to inform the development of more complete risk decision-making models with the ultimate objective of improving prevention and intervention programs for risk behavior and, thus, reducing the high cost of these behaviors to society.

Data availability statementsThe datasets generated during and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

This research has been funded by the Regional Ministry of Economy and Knowledge, Junta de Andalucía, to Alberto Megías Robles (UMA18-FEDERJA-13 and EMERGIA20_00056).