Depression is a common mental health condition and a main risk factor for suicide. Narrative therapy aims to reframe beliefs through storytelling. Despite evidence of effectiveness, there is a lack of evaluation for specific adult populations. This meta-analysis evaluated the effect of narrative therapy on depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. Only 2 of the included studies examined patients with depression, highlighting the need for further research on this specific population.

MethodsA comprehensive search of PubMed, Web of Science (all databases), the Cochrane Library, CINAHL, CNKI, and CBMdisc was conducted in April 2024. Study selection and data extraction were conducted by two researchers independently. The Cochrane tool and GRADEPro GDT tool were utilised to determine risk of bias and methodological quality of included studies. Stata17.0 was used for statistical analysis.

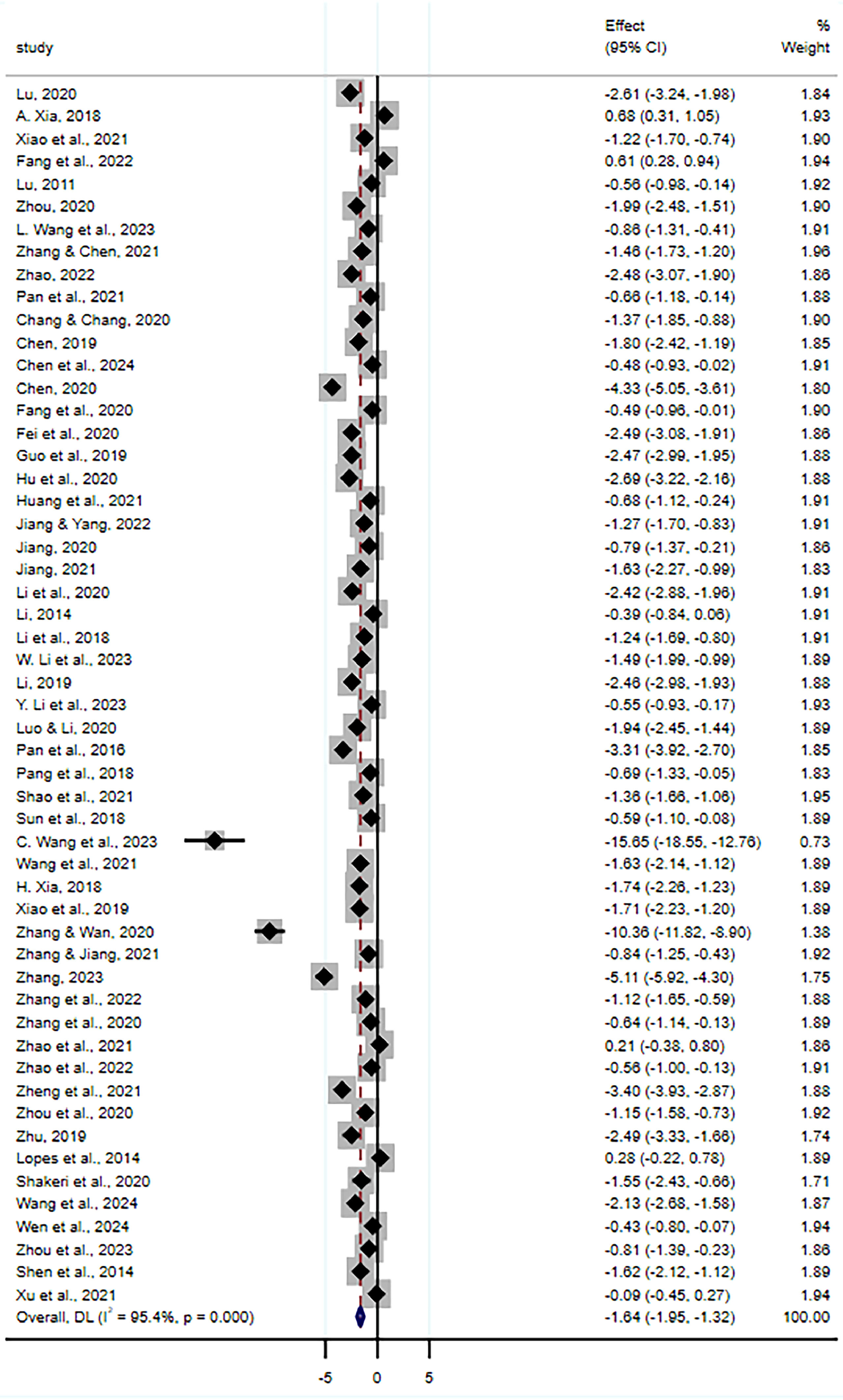

ResultsThe results showed that narrative therapy had a significant effect on depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders (SMD=-1.64; 95% CI, -1.95 to -1.32; p<.001; 4,879 participants; low-quality evidence). Sensitivity analysis showed that the results were robust and reliable.

DiscussionThis meta-analysis found that narrative therapy appears to have a significant effect on depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. However, the study is limited by a predominance of Chinese studies and low quality of evidence. Future research is needed to confirm these findings.

Depression is a common mental health condition, affecting millions of people. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global prevalence of clinical depression is currently estimated to be 4.4%, equal to more than 340 million people worldwide ("Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates," 2017). The prevalence of clinical depression is increasing and is estimated to be the number one disease burden globally in 2030 (Malhi & Mann, 2018). The Lancet-World Psychiatric Association Major Report on Depression reported that depression is a leading cause of avoidable suffering. It calls for policy makers to consider the social and structural determinants of depression and to devise a coordinated public health approach to prevention and intervention (Herrman et al., 2022). Depression not only causes serious psychological and emotional distress to individuals but also imposes a significant socio-economic burden via unemployment, reduced productivity and increased healthcare costs. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study shows that depression is one of the most disabling mental disorders and one of the top 25 leading causes of global burden in 2019 (Vos et al., 2020). Another serious hazard of depression is reflected in its potential to lead to an increased risk of suicide. A meta-analysis reported that people with depression have almost 20 times the risk of dying by suicide, with a standardized mortality rate of 19.7% (Chesney et al., 2014). Thus, depression is not only an individual health problem but also a public health challenge that requires global attention and intervention.

Currently, the most effective treatments for depression are medication and psychotherapy (Kamenov et al., 2016). Psychotherapy is considered the first-line treatment for depression (Cuijpers et al., 2023). Narrative therapy, as a relatively new approach to psychotherapy, aims to adapt the life story a person tells to bring about positive change and better mental health (Effat Ghavibazou et al., 2022). By listening to the negative narratives of depressed patients, therapists look for unique experiences of successful problem-solving in the past. By focusing on positive explanations, they help the patient to "rewrite" the story and develop an alternative, more positive narrative of life (Seo et al., 2015). Therefore, narrative therapy may be beneficial in the treatment of depression.

The popularity of narrative therapy is closely related to the postmodernist trend in contemporary philosophy (Polkinghorne, 2004). In this regard, it is necessary to distinguish the influence of modernism and postmodernism on the ideas and methods of psychotherapy. Modernism emphasizes the truth of objective facts, which is considered immutable and not affected by observers or methods of observation (Sherry, 2017). Post-modernism is more inclined to the subjective truth, that is, the truth changes with the observation process and is affected by the language and background environment (Epstein, 1995). The combination of narrative theory and postmodernism provides the foundation for the development of narrative psychology.

In the 1980s, the founders and representatives of narrative therapy, Australian clinical psychologist Mike White and New Zealand's David Epston, put forward the theory of narrative therapy and systematically elaborated their views and methods about narrative psychotherapy in their seminal book Story, Knowledge, Power - The Power of Narrative Therapy (White & Epston, 1990). Narrative therapy focuses on the relationship between the person and the problem, emphasizing that the problem itself is the problem, not the person (Zadehmohammadi et al., 2013). Pioneers of narrative therapy such as Mike White noted that people feel problems because their life stories do not adequately represent their true experiences, resulting in inconsistencies between internal experiences and external narratives (White & Epston, 1990). Traditional psychotherapy tends to explain the visitor's problem through diagnosis, but this may lead to internalization of the problem by the visitor as a label for themselves. This in turn creates a sense of self-problem, which is not conducive to the resolution of the problem. Conversely, narrative therapy strives to separate the person from the problem to solve the problem in a more effective way (Hutto & Gallagher, 2017).

Narrative therapy involves several methods and strategies. Firstly, orchestration and interpretation: the therapist helps the individual to organize the story so that they become an observer of their own story. They examine it with the therapist, exploring the events in their life and their significance and jointly examining the issues present in the story (Petrovic et al., 2022). Secondly, problem externalization: separating the problem from the individual and helping the individual to view the problem objectively and to have the ability and motivation to solve it (Rice, 2015). Thirdly, deconstruction: the therapist works with the individual to break down the story into smaller parts, clarifying the issues and making them easier to understand and process (Wallis et al., 2010). Fourthly, looking for unique outcomes: life cannot always be affected by negative events, there are always positive moments and this is where narrative therapy pays special attention to the unique outcomes. With the help of therapists, individuals will begin to focus on the positive parts of their lives, reinterpreting their life stories and coping with their problems (Gonçalves et al., 2009).

There have been several studies exploring narrative therapy with encouraging results. Studies have shown that narrative therapy can be effective in aiding the psychological recovery of cancer survivors (Benish-Weisman et al., 2013) and reducing levels of depression and anxiety in patients with amphetamine addiction (Shakeri et al., 2020). Another study using a one-sample repeated measures design showed that narrative therapy improved depressive symptoms and interpersonal outcomes in adults with major depressive disorder (Vromans & Schweitzer, 2011). In addition, nurses intervening with depressed patients in narrative therapy with an emotional approach appeared to be effective in improving positive emotions, cognitive-emotional outcomes such as hope and reducing depressive symptoms (Seo et al., 2015). These studies provide preliminary evidence to support the effectiveness of narrative therapy in improving symptoms of depression.

However, it is not clear how effective narrative therapy is in clinical practice, especially as a treatment for depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. This may be in part due to small sample sizes, short follow-up periods in existing trials and the absence of systematic evaluations of the effectiveness of interventions in which narrative therapy has been applied to depressive symptoms in adults. Therefore, this study conducted a systematic review and synthesis of the existing literature to determine the overall effectiveness of narrative therapy on depressive symptoms in adults.

Materials and methodsRegistrationThis review is registered with PROSPERO (Number: CRD42024524680). Results are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (see Supplementary Table S1).

Data sources and Search strategyFour English electronic databases were searched: PubMed, Web of Science (all databases), the Cochrane Library and CINAHL, and two Chinese electronic databases: CNKI and CBMdisc from inception to March 15, 2024. The latest update to the search occurred on April 30, 2024. In addition, the list of references included in the studies were searched manually to identify studies that might meet the eligibility criteria. Details of the search strategy for each database are given in Supplementary Text S1.

Eligibility criteriaThe selection of included studies followed predefined criteria established through the Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study (PICOS) strategy. The focus of the review is randomized controlled trials of the effects of narrative therapy on depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders (aged≥18 years). Narrative therapy, as described in this study, aims to reframe beliefs through storytelling. It focuses on the relationship between the person and the problem, emphasizing that the problem itself is the problem, not the person. It involves methods such as orchestration and interpretation, problem externalization, deconstruction, and looking for unique outcomes. Narrative medicine and narrative nursing examined in the included studies share the core elements and mechanisms with narrative therapy. For example, they also involve listening to patients' stories, identifying problems, and working towards positive change. The focus on the patient's narrative and the use of storytelling as a therapeutic tool are common features among these approaches, which justifies their inclusion in our study. We excluded studies in which changes in depressive symptoms could not be assessed by standardized assessment scales or other relevant outcomes. There are no restrictions set for year of publication. For more information on eligibility criteria, see Supplementary Table S2.

Study selectionStudy selection was completed by two researchers Firstly, we imported literature retrieved from various databases into EndnoteX9 (a literature management software) and excluded duplicates. The two researchers then independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the literature and screened the literature for further review of the full text based on predetermined eligibility criteria. Once the studies to be included were identified, the two researchers again independently performed data extraction. Where disagreements existed between the two researchers during the study selection process, these were resolved through discussion or arbitration with a third researcher.

Data extractionTwo researchers independently carried out the data extraction using a pre-designed standardized data extraction form and any disagreements were discussed and resolved by a third researcher. The high percentage of agreement (96.30%) between the raters indicates a reliable assessment method. The two researchers were in agreement on 52 out of 54 samples, suggesting that the data screening and coding process was consistent. This high level of consistency suggests that our data collection and analysis methods were robust.

Extracted data elements included publication details (first author, year of publication, and country/region of publication), participant information (sample size, age, gender, and participant characteristics), intervention details (treatment duration and characteristics of the intervention group versus the control group), and outcome metrics (assessment of depressive symptoms, dislodgement, whether or not analyses of intent were conducted, risk of bias assessed using ROB2, and pre-and post-intervention means and standard deviations for each study group). When studies reported results at different time points, only the results of the first assessment after the completion of all interventions were extracted. At the time of data extraction, we contacted authors if the data required for meta-analysis were not provided in the original literature. If we did not hear back within a week, we contacted them again. If no response was received, the article was excluded.

Quality evaluationThe quality assessment covered both the risk of bias assessment and the quality of evidence assessment of the studies. Two researchers independently assessed the risk of bias using the Cochrane tool for assessing the Risk of Bias in Randomized Trials, version 2 (RoB 2). We followed the five assessment domains set out in RoB 2, including: randomization process, deviations from the intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported results. The risk of bias in each area is categorized into three levels: low risk of bias, partial concern, and high risk of bias. Disagreements arising between two researchers were discussed and resolved with the involvement of a third researcher.

Two researchers used GRADEpro GDT (Recommendation, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation Profiler Guideline Development Tool) to assess the quality of evidence. The quality of evidence was graded into four levels: high, moderate, low, and very low. The decline in the quality of evidence can be due to study limitations (risk of bias), inconsistent results, circumstantial evidence, and biased reporting.

Statistical analysisStata 17.0 software (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA) was used for meta-analysis in this study. We used standardized mean differences (SMD) as the aggregated effect size measure. The SMD was calculated using Cohen's d method, which is defined as the difference in means between the experimental and control groups divided by the pooled standard deviation. This approach allowed us to combine the results from different studies and obtain an overall estimate of the treatment effect on depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. For the meta-analysis of continuous data, we used maximum likelihood estimation and calculated prediction intervals to reflect the 95% confidence intervals for the true standardized mean deviation (SMD) expected in similar studies (IntHout et al., 2016). The Q statistic was applied to test for heterogeneity, with a p-value of less than 0.05 indicating heterogeneity between studies. In addition, the I² statistic was used to assess the degree of heterogeneity, graded as low (I²=25%), moderate (I²=50%) or high (I²=75%). A small p-value for the Q statistic or a high I² statistic (I²≥50%) would indicate significant heterogeneity. In such cases, a random effects model was used to calculate weighted effect sizes. To explore the reasons for heterogeneity, subgroup analyses, sensitivity analyses, and meta-regressions were conducted, considering factors such as age, country/region of publication, type of study population, duration of intervention, and type of control group. Plot, Egger's test, and Begg's test were analyzed to detect publication bias, with p<.05 indicating possible publication bias.

ResultsStudy selectionThe study selection process has been presented in detail in Fig. 1. The initial search located 6,783 studies from six literature repositories. Using the automatic de-duplication tool within EndnoteX9, 407 duplicates were excluded. 5,991 studies were excluded during title and abstract screening. During the full-text assessment stage, 330 studies were excluded for the following main reasons: non-randomized trials (n=83), not meeting the inclusion criteria (n=242), non-English or Chinese literature (n=1), retractions (n=3), and full-text unavailability (n=2). In addition, 2 additional studies that met the criteria were included by reading the reference lists of existing review articles. Overall, 54 studies were included in the systematic evaluation and meta-analysis. All included references are listed in Supplementary Text S2.

Characteristics of the included studiesParticipantsParticipant-related information for each study has been listed in Table 1. The studies were published in the period 2014–2024. The regions in which these studies were conducted included China (n=52), Portugal (n=1) and Iran (n=1). The total sample size was 4,879 participants with sample sizes ranging from 40 to 280 participants. Of the studies reporting age (n=44), 13 studies (29.55%) had participants with a mean age ≥65 years, and these studies were considered to have participants who were elderly for this study. Of the studies that reported gender (n=47), the percentage of female participants ranged from 17.19% to 100.00%, with 8 studies (17.02%) having all female participants. All studies reported participant withdrawals, with 47 studies (87.04%) having 0 withdrawals and the remaining studies having between 2–19 dropouts.

Basic characteristics and quality evaluation of the included literature.

| Study | Participants | Treatments | Experiment | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Country | N(Exp/Con) | Gender(Exp/Con) | Age (Mean±SD) | Inclusion | Experimental group | Control group | Frequency and duration | Drop-outs (Exp/Con) | ITT | Risk of bias | Depression measurement | |

| Lu, 2020 | 2020 | China | 36/36 | Female:38.89%/41.67% | Exp: 58.14±6.29Con: 58.53±6.47 | Patients with advanced cancer | A five-step narrative therapy | Routine education and psychological counseling intervention | 30–45 min/time, 1–3 times/week, for 2 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | PHQ-9 |

| A. Xia, 2018 | 2018 | China | 60/60 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 30.6±3.4Con: 31.4±3.1 | Patients with laparoscopic polycystic ovary syndrome | Routine nursing and Narrative psychotherapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Xiao et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 40/40 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 35.68±6.75Con: 35.95±4.21 | High-risk pregnant women | Routine nursing and Narrative psychotherapy | Routine nursing | 45 min/time, at least 3 times/week, for 8 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Fang et al., 2022 | 2022 | China | 74/73 | Female:48.65%/50.68% | Exp: 52.89±5.88Con: 52.66±6.15 | Patients with advanced gastric cancer | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Lu, 2011 | 2011 | China | 45/45 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 27.5±4.1Con: 26.3±3.6 | Parturients after delivery | General supportive psychological nursing and Narrative therapy | General supportive psychological nursing | 60 min/time, Once a week in the first month, once every two weeks in the second and third months | 0/0 | No | L | HAMD |

| Zhou, 2020 | 2020 | China | 50/50 | Female:26.00%/30.00% | Exp: 60.23±3.05Con: 59.21±3.03 | Lung cancer patients | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| L. Wang et al., 2023 | 2023 | China | 39/45 | / | / | Patients with radiotherapy for advanced cervical cancer | Routine psychological nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine psychological nursing | 1.5h/time, 1 time/week, for 6 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhang & Chen, 2021 | 2021 | China | 138/142 | Female:46.38%/46.48% | Exp: 66.45±5.6Con: 66.36±5.3 | Elderly patients with coronary heart disease | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, 2 times/week, for 4 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhao, 2022 | 2022 | China | 40/40 | Female:42.50%/47.50% | Exp: 48.93±5.46Con: 48.89±5.41 | Patients with liver cirrhosis and ascites | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SCL-90 |

| Pan et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 30/30 | Female:50.00%/53.33% | / | Convalescent patients with occupational acute chemical toxic encephalopathy | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, 1 time/week, for 6 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Chang & Chang, 2020 | 2020 | China | 40/40 | Female:40.00%/47.50% | Exp: 48.93±5.46Con: 48.89±5.41 | Patients on hemodialysis | Routine dialysis nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine dialysis nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Chen, 2019 | 2019 | China | 29/29 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 36.17±1.54Con: 36.13±1.57 | Nurses in the outpatient and emergency departments | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine nursing | 2 times/week, for 3 months | 0/0 | No | L | / |

| Chen et al., 2024 | 2024 | China | 39/39 | Female:20.51%/25.64% | Exp: 49.18±13.98Con: 48.54±16.26 | Patients with spinal cord injury during rehabilitation | Routine psychological nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine psychological nursing | 30 min/time, 2 times/week | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Chen, 2020 | 2020 | China | 50/50 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 31.35±2.47Con: 30.27±2.38 | Patients with early-onset severe eclampsia | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Fang et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 35/35 | Female:48.57%/42.86% | Exp: 48.14±10.83Con: 48.45±11.26 | Patients with liver failure | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, once every 5 days, 3 times in total, for 2 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Fei et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 40/40 | Female:35.00%/30.00% | Exp: 56.19±5.00Con: 59.21±2.03 | Patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, 1 time/week, for 4 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Guo et al., 2019 | 2019 | China | 50/50 | Female:48.00%/44.00% | Exp: 51.6±6.3Con: 52.3±5.8 | Patients with advanced cancer | Routine nursing and A five-step narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30–40 min/time, 1–2 times/week, for 2 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | PHQ-9 |

| Hu et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 56/56 | Female:44.40%/38.50% | / | Patients with end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine psychological nursing | 30 min/time, 1 time/week, for 1 month; after 1 month, change once for 2 weeks, for 2 months | 2/4 | No | L | SDS |

| Huang et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 43/43 | Female:69.05%/63.41% | Exp: 63.09±13.37Con: 61.76±12.15 | Patients after lower extremity bone and joint replacement | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | 45–60 min/time, 5 times in total | 1/2 | No | L | SDS |

| Jiang & Yang, 2022 | 2022 | China | 50/50 | Female:45.83%/38.78% | Exp: 70.08±6.71Con: 70.52±6.25 | Elderly maintenance hemodialysis patients | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30–45 min/time, 1 time/week, for 3 months | 2/1 | No | L | HADS |

| Jiang, 2020 | 2020 | China | 25/24 | Female:28.00%/37.50% | Exp: 45.6±8.1Con: 44.8±6.4 | Young and middle-aged patients with stroke | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | 30–60 min/time, 2 times/week, for 4 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Jiang, 2021 | 2021 | China | 25/25 | Female:32.00%/28.00% | Exp: 65.32±3.62Con: 66.24±3.53 | Patients with cerebral infarction | Routine cognitive rehabilitation exercises and Narrative nursing | Routine cognitive rehabilitation exercise | 1 h/time, 2 times/week, for 4 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Li et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 65/63 | Female:35.38%/34.92% | Exp: 57.25±6.51Con: 58.02±6.72 | Patients with stroke | Routine nursing and Narrative medical nursing | Routine nursing | For 3 months | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Li, 2014 | 2014 | China | 38/38 | Female:47.37%/44.74% | Exp: 40.9±11.1Con: 41.2±10.3 | Diabetic patients who self-administered insulin for the first time | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Li et al., 2018 | 2018 | China | 46/46 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 36.87±5.36Con: 35.22±5.36 | Young patients with breast cancer undergoing hemotherapy | Routine nursing and Narrative medicine psychological intervention | Routine nursing | 40–60 min/time | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| W. Li et al., 2023 | 2023 | China | 40/40 | Female:32.50%/37.50% | Exp: 35.14±3.64Con: 35.49±3.24 | Young spouses with myocardial infarction | Narrative psychological intervention | Routine psychological nursing | 30 min/time once every 2 weeks, for 12 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Li, 2019 | 2019 | China | 50/50 | / | / | Patients with advanced lung cancer | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, 1 time/week, for 8 weeks | 1/2 | No | S | SDS |

| Y. Li et al., 2023 | 2023 | China | 55/55 | Female:40.00%/32.73% | Exp: 68.25±8.10Con: 68.56±8.37 | Elderly patients with chronic kidney disease | Routine nursing and Narrative medicine | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Luo & Li, 2020 | 2020 | China | 45/45 | / | / | Nurses in emergency department | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine nursing | 20 min/time, 1 time/week, for 4 weeks | 2/0 | No | S | HAMD |

| Pan et al., 2016 | 2016 | China | 50/50 | Female:44.00%/50.00% | Exp: 65.5±3.6Con: 67.3±3.1 | Patients with stroke in the sequelae stage | Routine nursing and Narrative medicine intervention | Routine nursing | 60 min/time, 1–3 times in total, adjust according to the specific situation | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Pang et al., 2018 | 2018 | China | 20/20 | / | / | Car accident survivors | Routine nursing and Early narrative treatment intervention | Routine nursing | 50 min/time, 1 time/week, 5 times in total | 0/0 | No | L | HAMD |

| Shao et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 108/102 | Female:37.04%/34.31% | Exp: 74.1±5.1Con: 73.5±4.9 | Elderly patients with chronic diseases | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Sun et al., 2018 | 2018 | China | 31/31 | Female:41.94%/45.16% | Exp: 60.77±11.23Con: 59.15±12.46 | Patients with perioperative roliferative diabetic retinopathy | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | 30–40 min/time, 3–4 times in total | 0/0 | No | L | HAMD |

| C. Wang et al., 2023 | 2023 | China | 30/30 | Female:43.33%/27.50% | Exp: 39.2±8.6Con: 36.2±10.1 | Surgical patients | Pre-operative visit and Narrative therapy | Pre-operative visit | at least 1 time before surgery | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Wang et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 40/40 | Female:77.50%/72.50% | Exp: 46.12±10.14Con: 45.34±10.53 | Patients with insomnia disorder | Narrative therapy | Cognitive-behavioral therapy | 50 min/time, 1 time/week, for 8 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| H. Xia, 2018 | 2018 | China | 40/40 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 28.69±2.12Con: 29.02±2.02 | Patients with placenta previa | Narrative psychotherapy | Routine psychological intervention | 1 time/week, 6 times in total | 0/0 | No | L | HAMD |

| Xiao et al., 2019 | 2019 | China | 40/40 | Female:45.00%/50.00% | Exp: 52.2±3.8Con: 52.8±4.2 | Patients with lacunar cerebral infarction | Routine cognitive function rehabilitation exercise and Narrative medical nursing | Routine cognitive function rehabilitation exercise | 60 min/time, 2 times/week, for 4 weeks | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhang & Wan, 2020 | 2020 | China | 59/47 | Female:44.07%/46.81% | Exp: 55.98±14.78Con: 56.98±15.89 | Patients with chronic pain | Routine nursing and Narrative medical nursing interventions | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | HAMD |

| Zhang & Jiang, 2021 | 2021 | China | 50/50 | Female:46.00%/44.00% | Exp: 65.00±12.64Con: 66.00±16.69 | Patients with malignant tumors | Routine nursing and Narrative medicine | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhang, 2023 | 2023 | China | 51/51 | Female:50.98%/45.10% | Exp: 75.23±2.69Con: 65.67±10.89 | Elderly patients with chronic heart failure | Routine nursing and A five-step narrative therapy | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | The Chinese simplified version of the Depression-Anxiety-Pressure Scale |

| Zhang et al., 2022 | 2022 | China | 32/32 | Female:18.75%/15.63% | Exp: 68.43±4.30Con: 68.10±4.03 | Elderly patients with stroke | Routine nursing and Narrative medical nursing intervention | Routine nursing | 30 min/time, 2 times/week, for 3 months | 0/0 | No | L | CES-D |

| Zhang et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 42/41 | Female:69.05%/82.93% | Exp: 48.86±13.72Con: 47.95±10.34 | The main caregivers of stroke patients | Routine nursing and Narrative therapy | Routine nursing | 30–45 min/time, 2 times/week, for 4 weeks | 7/12 | No | S | SDS |

| Zhao et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 20/25 | Female:40.00%/28.00% | Exp: 43.64±7.23Con: 41.35±9.16 | Surgical patients with adrenal hypercortisolism | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhao et al., 2022 | 2022 | China | 42/42 | Female:45.24%/38.10% | Exp: 36.98±7.24Con: 37.50±7.38 | Patients with depression | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zheng et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 68/68 | Female:33.82%/36.76% | / | Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhou et al., 2020 | 2020 | China | 50/50 | Female:32.00%/40.00% | Exp: 37.93±6.35Con: 36.65±7.75 | Patients undergoing heart valve replacement | Narrative intervention | Routine psychological nursing | 20–30 min/time, 2–3 times/week, continue until patient discharge | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhu, 2019 | 2019 | China | 20/20 | Female:40.00%/45.00% | Exp: 67.5±4.1Con: 66.9±3.9 | Patients with Senile Disease | Routine nursing and Narrative medicine | Routine nursing | 40–60 min/time, 3 times in total | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Lopes et al., 2014 | 2014 | Portugal | 34/29 | / | / | Patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder | Narrative therapy | Cognitive-behavioral therapy | 20–60 min/sessions, Sessions 1–16 were scheduled weekly, whereas sessions 17–20 were scheduled every other week | 0/0 | Yes | L | BDI-II |

| Shakeri et al., 2020 | 2020 | Iran | 20/20 | / | / | People with amphetamine addiction | Narrative therapy | Routine psychiatric nursing | / | 7/7 | No | S | BDI-II |

| Wang et al., 2024 | 2024 | China | 40/40 | Female:47.50%/45.00% | Exp: 75.32±3.42Con: 75.54±3.42 | Elderly patients with fracture complicated with cerebrovascular accident | Personalized narrative nursing mode | Routine nursing | for 3 months | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Wen et al., 2024 | 2024 | China | 60/60 | Female:56.67%/43.33% | Exp: 71.48±7.82Con: 69.80±8.94 | Postoperative patients with severe lung cancer | Routine care and The five-step narrative nursing method based | Routine analgesic and psychological care | 30–45 min/time, 1–2 times/week, for 1 month | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Zhou et al., 2023 | 2023 | China | 25/25 | Female:36.00%/40.00% | Exp: 59.43±5.42Con: 59.44±5.44 | Patients after bone and joint replacement | Routine nursing and Narrative nursing intervention | Routine nursing | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Shen et al., 2014 | 2014 | China | 42/40 | Female:100.00%/100.00% | Exp: 27.94±5.07Con: 28.45±4.13 | Patients with placenta previa | Narrative psychotherapy | Routine psychological care | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

| Xu et al., 2021 | 2021 | China | 60/60 | / | / | Patients with Malignant Tumors Undergoing Chemotherapy | Targeted nursing intervention centering on narrative nursing | Targeted nursing intervention | / | 0/0 | No | L | SDS |

Notes:

N: Total study population.

ITT: Intention-to-treat analysis.

L: Low risk; S: Some concerns.

CES-D: Center for epidemiologic studies depression; BDI-II: Beck depression inventory-II; SCL 90: Symptom check list 90; SDS: Self-rating depression scale; HAMD: Hamilton depression scale; PHQ-9: Patient health questionnaire; HADS: The hospital anxiety and depression scale.

The populations with somatic disorders included in the studies included: patients with cancer (n=10), patients with stroke (n=4), patients with heart disease (n=4), patients with liver disease (n=2), nurses (n=2), patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy (n=2), patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n=2), patients with placenta praevia (n=2), and patients with depression (n=2), patients after bone arthroplasty (n=2), patients on haemodialysis (n=2), patients with cerebral infarction (n=2), patients with laparoscopic polycystic ovary syndrome (n=1), high-risk pregnant women (n=1), women in labour (n=1), patients recovering from occupational acute chemical toxic encephalopathy (n=1), patients with convalescent spinal cord injury (n=1), patients with premature eclampsia of severe type (n=1), diabetic patients self-administering insulin for the first time (n=1), young spouses with myocardial infarction (n=1), elderly patients with chronic kidney disease (n=1), survivors of car accidents (n=1), elderly patients with chronic diseases (n=1), surgical patients (n=1), patients with insomnia disorders (n=1), patients with chronic pain (n=1), and primary caregivers for stroke patients (n=1), surgical patients with adrenocorticotropic hyperalgesia (n=1), patients with geriatric disorders (n=1), amphetamine addicts (n=1), and elderly patients with fractures combined with cerebrovascular accidents (n=1).

The intervention group and the control groupNarrative therapy was used in all trial groups. In studies reporting the duration of a single intervention, the duration of each intervention ranged from 20 to 60 minutes. In studies reporting frequency of intervention and total length of intervention, the frequency of intervention ranged from 1–3 times per week and the total length of intervention ranged from 2 to 24 weeks. The control group consisted of cognitive-behavioral therapy, preoperative visits, routine psychological care, and routine treatment and care. The control and intervention groups of the studies were conducted in parallel, maintaining the same duration and frequency of intervention. All 54 studies were two-arm trials. All studies we included measured depressive symptoms using standardized assessment scales such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD), and other validated instruments. The details of standardized assessment scales are given in Table 1.

Risk of bias and confidence in the cumulative evidenceFigs. 2 and 3 show the risk of bias assessment. Regarding the randomization process, 54 studies were rated as low risk. Of these, 25 studies explicitly stated the words "randomized grouping" in the article, 24 studies stated that the method of randomization used was random number tables, three studies stated that the method of randomization used was random lotteries (Chen, 2019; Jiang & Yang, 2022; Zhang, 2023), one study stated that the method of randomization used was computer-generated random number tables (Lu, 2020), and one study stated that the method of randomization used was the coin toss method (Xiao et al., 2021). In terms of deviating from expected interventions, none of the 54 studies used blinding of subjects and researchers, which could have affected the results. However, due to the nature of psychological interventions, blinding is usually not possible. Only one study stated in the article that an intention-to-treat analysis was used (Lopes et al., 2014), and four studies with withdrawals did not use an intention-to-treat analysis (Li, 2019; Luo & Li, 2020; Shakeri et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020). After assessing the risk of bias in the 54 included studies, all were found to have a low risk of bias for missing outcome data, outcome measures, and selective outcome reporting. Ultimately, four studies were labeled as having some concern, while 50 studies were highlighted as having a low risk of bias. In addition, the GRADE assessment report indicated that the overall quality of evidence was rated as very low, suggesting a high degree of uncertainty and inherent limitations of the available evidence. For a more comprehensive risk of bias assessment and additional data, please see Supplementary Table S3.

According to the findings shown in Fig. 4, adults with somatic disorders experiencing depressive symptoms may significantly benefit from narrative therapy. The meta-analysis revealed a combined effect size of SMD=-1.64 (95% CI, -1.95 to -1.32), indicating a significant reduction in symptoms between the control and experimental groups. A Z-value of -10.30 (p<.001) reinforced this finding. Notably, heterogeneity was highly significant (I2=95.4%, p<.001; Q(53)=1160.76, p<.001) and subgroup and meta-regression analyses need to be used to assess significant influences contributing to the observed heterogeneity.

Effects of narrative therapy on adults with depressive symptoms. The meta-analysis revealed a pooled effect size of SMD=-1.64 (95%CI, -1.95 to -1.32), indicating a significant decrease in symptoms between the control and experimental groups. The heterogeneity was substantial and significant (I2=95.40%, p<.001).

To explore the significant influences on heterogeneity, subgroup analyses were conducted according to age, country, type of study population, duration of intervention, and type of control group (Table 2).

Subgroup analyses by mean age, country, type of study population, intervention duration and type of control group.

| Subgroups | Na | SMD | 95% CI | Z | p | I2 | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (yrs) | 44 | -1.69 | -2.03 to -1.34 | -9.62** | <0.001 | 95.50%** | <0.001 |

| < 65 | 31 | -1.73 | -2.19 to -1.27 | -7.39** | <0.001 | 96.00%** | <0.001 |

| ≥ 65 | 13 | -1.67 | -2.16 to -1.17 | -6.60** | <0.001 | 93.90%** | <0.001 |

| Country | 54 | -1.64 | -1.95 to -1.32 | -10.30** | <0.001 | 95.40%** | <0.001 |

| China | 52 | -1.67 | -1.99 to -1.36 | -10.38** | <0.001 | 95.50%** | <0.001 |

| Other countries | 2 | -0.60 | -2.38 to -1.19 | -0.65 | =0.513 | 91.90%** | <0.001 |

| Type of study population | 38 | -1.51 | -1.83 to -1.19 | -9.22** | <0.001 | 94.30%** | <0.001 |

| Adults with cancer | 10 | -1.22 | -1.90 to -0.54 | -3.52** | <0.001 | 96.00%** | <0.001 |

| Adults with depression | 2 | -0.15 | -0.98 to -0.67 | -0.36 | =0.719 | 83.90%* | =0.013 |

| Pregnant and lying-in woman | 4 | -1.27 | -1.82 to -0.73 | -4.55** | <0.001 | 81.10%** | =0.001 |

| Nurse | 2 | -1.89 | -2.28 to -1.49 | -9.44** | <0.001 | 0.00% | =0.726 |

| Adults with stroke | 6 | -1.83 | -2.53 to -1.13 | -5.12** | <0.001 | 89.80%** | <0.001 |

| Adults with liver disease | 2 | -1.48 | -3.43 to -0.48 | -1.48 | =0.139 | 96.30%** | <0.001 |

| Adults with heart disease | 4 | -2.24 | -3.37 to -1.11 | -3.88** | <0.001 | 96.20%** | <0.001 |

| Adults on hemodialysis | 2 | -1.31 | -1.64 to -0.98 | -7.89** | <0.001 | 0.00% | =0.762 |

| Adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 2 | -3.04 | -3.74 to -2.35 | -8.61** | <0.001 | 71.00% | =0.063 |

| Adults with proliferative diabetic retinopathy | 2 | -1.54 | -3.40 to 0.33 | -1.61 | =0.107 | 95.70%** | <0.001 |

| Adults after bone and joint replacement | 2 | -0.73 | -1.08 to -0.38 | -4.06** | <0.001 | 0.00% | =0.730 |

| Intervention duration (wks) | 25 | -1.38 | -1.67 to -1.10 | -9.47** | <0.001 | 88.30%** | <0.001 |

| < 6 | 11 | -1.34 | -1.78 to -0.91 | -6.04** | <0.001 | 88.80%** | <0.001 |

| 6–12 | 7 | -1.51 | -1.90 to -1.12 | -7.53** | <0.001 | 77.10%** | <0.001 |

| ≥ 12 | 7 | -1.32 | -2.03 to -0.60 | -3.60** | <0.001 | 93.00%** | <0.001 |

| Type of control group | 52 | -1.56 | -1.86 to -1.25 | -10.10** | <0.001 | 95.00%** | <0.001 |

| Cognitive-behavioral therapy | 2 | -0.67 | -2.54 to 1.19 | -0.71 | =0.479 | 96.4%** | <0.001 |

| Routine cognitive rehabilitation exercise | 2 | -1.68 | -2.08 to -1.28 | -8.21** | <0.001 | 0.00% | =0.838 |

| Routine nursing | 37 | -1.67 | -2.06 to -1.27 | -8.30** | <0.001 | 95.90%** | <0.001 |

| Routine psychological nursing | 11 | -1.36 | -1.82 to -0.90 | -5.83** | <0.001 | 89.70%** | <0.001 |

Notes:

Cohen's meta-analysis pooling method was employed, utilizing a random-effects inverse variance model for estimating tau2.

A minimum requirement of n ≥ 2 was set for the number of studies within each subgroup.

*p < .05, **p < .01.

SMD, Standardized Mean Difference; CI, confidence interval; yrs, years; wks, weeks.

Grouping the included studies according to mean age revealed that narrative therapy significantly reduced depressive symptoms in the adult group (mean age <65 years) (SMD=-1.73; 95% CI, -2.19 to -1.27; Z=-7.39, p<.001) and in the elderly group (mean age ≥65 years) (SMD=-1.67; 95% CI, -2.16 to -1.17; Z=-6.60, p<.001). However, the difference in effect sizes (SMD=-1.73 for the adult group vs. SMD=-1.67 for the elderly group) was not statistically significant. Moreover, there was a high degree of heterogeneity in the adult group (mean age <65 years) (I2=96.00%, p<.001) and in the elderly group (mean age ≥65 years) (I2=93.90%, p<.001).

Grouping the included studies according to country reveals that the implementation of narrative therapy (SMD=-1.67; 95% CI, -1.99 to -1.36; Z=-10.38, p<.001) on Chinese individuals has a significant effect in improving depressive symptoms, but with a high degree of heterogeneity (I2=95.50%, p<.001).

Grouping the included studies according to the type of study population revealed that narrative therapy was only effective for adults with cancer (SMD=-1.22; 95% CI, -1.90 to -0.54; Z=-3.52, p<.001), pregnant women (SMD=-1.27; 95% CI, -1.82 to -0.73; Z=-4.55, p<.001), nurses (SMD=-1.89; 95% CI, -2.28 to -1.49; Z=-9.44, p<.001), adult patients with stroke (SMD=-1.83; 95% CI, -2.53 to -1.13; Z=-5.12, p<.001), adults with heart disease (SMD=-2.24; 95% CI, -3.37 to -1.11; Z=-3.88, p<.001), adult patients receiving hemodialysis (SMD=-1.31; 95% CI, -1.64 to -0.98; Z=-7.89, p<.001), and adults with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (SMD=-3.04; 95% CI, -3.74 to - 2.35; Z=-8.61, p<.001) and adult patients undergoing bone and joint replacement (SMD=-0.73; 95% CI, -1.08 to -0.38; Z=-4.06, p<.001) were significant. There was no heterogeneity in the group of nurses (I2=0.00%; p=.726), the group of adult patients undergoing hemodialysis (I2=0.00%; p=.762), or the group of adult patients undergoing bone and joint replacement (I2=0.00%; p=.730), and the difference was not statistically significant. However, the groups of adult patients with cancer (I2=96.00%; p<.001), pregnant women (I2=81.10%; p=.001), adult patients with stroke (I2=89.80%; p<.001), adult patients with cardiac disease (I2=96.20%; p<.001), and adult patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (I2 =71.00%; p<.063) were highly heterogeneous.

Grouping the included studies according to intervention duration, heterogeneity was higher in all three groups for intervention durations <6 weeks, at 6–12 weeks (including 6 weeks and excluding 12 weeks), and ≥12 weeks (I2=88.80%, p<.001; I2=77.10%, p<.001; I2=93.00%, p<.001). Intervention durations were <6 weeks (SMD=-1.34; 95% CI, -1.78 to -0.91; Z=-6.04, p<.001), at 6–12 weeks (SMD=-1.51; 95% CI, -1.90 to -1.12; Z=-7.53, p<.001), and ≥12 weeks (SMD=-1.32; 95% CI. -2.03 to -0.60; Z=-3.60, p<.001) had a significant effect on depressive symptoms.

Grouping the included studies according to the type of control group, it was possible to find that narrative therapy significantly reduced depressive symptoms compared with the routine cognitive rehabilitation exercise group (SMD=-1.68; 95% CI, -2.08 to -1.28; Z=-8.21, p<.001), the routine nursing group (SMD=-1.67; 95% CI, -2.06 to -1.27; Z=-8.30, p<.001), and the routine psychological nursing group (SMD=-1.36; 95% CI, -1.82 to -0.90; Z=-5.83, p<.001). There was no heterogeneity in the routine cognitive rehabilitation exercise group (I2=0.00%, p=.838), but the routine nursing group (I2=95.90%, p<.001) and the routine psychological nursing group (I2=89.70%, p<.001) had higher heterogeneity. Supplementary Fig. S1a–e provides a detailed illustration of the aforementioned information.

Sensitivity analysesThree sensitivity analysis methods were used to assess the impact of individual studies on the population estimates, including leave-one-out analysis, a fixed-effect inverse variance model and Hedges' g test. The results showed that the overall results were relatively stable and not significantly affected. Table 3 details the revised effect models and effect size changes. Details of the analyses are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2a–c.

Sensitivity analyses.

| Primary analyses | Na | SMD | 95% CI | p | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect model (Cohen’ d) | |||||

| Random effect model | 54 | -1.64** | -1.95 to -1.32 | <0.001 | Q (53) = 1160.76, p <0.001; I2 = 95.40% |

| Fixed effect model | 54 | -1.19** | -1.26 to -1.13 | <0.001 | Q (53) = 1160.76, p <0.001; I2 = 95.40% |

| Effect size (Random effect model) | |||||

| Cohen’ d | 54 | -1.64** | -1.95 to -1.32 | <0.001 | Q (53) = 1160.76, p <0.001; I2 = 95.40% |

| Hedges’ g | 54 | -1.62** | -1.93 to -1.31 | <0.001 | Q (53) = 1139.38, p <0.001; I2 = 95.30% |

Notes:

*p < .05, **p < .01.

After excluding the outliers with effect sizes greater than 5 (Wang et al., 2023; Zhang & Wan, 2020; Zhang, 2023), we recalculated the average effect of narrative therapy. The recalculated meta-analysis revealed a combined effect size of SMD= -1.34 (95% CI, -1.60 to -1.07), signifying a significant reduction in symptoms between the control and experimental groups. A Z-value of -9.74 (p<.001) strengthened this finding. Heterogeneity was highly significant (I2=93.9%, p<.001; Q(50)=820.39, p<.001). Details of the analyses are provided in Supplementary Fig. S2d.

Publication biasPublication bias was assessed using the funnel plot, Begg test, and Egger test. Funnel plot observations showed relative asymmetry. Begg test results (p<.05) and Egger test results (p<.05) indicated the presence of significant publication bias, which may affect the observed results. More detailed information can be found in Supplementary Figu. S3a–c.

Meta-regressionWe conducted meta-regression analyses examining factors such as mean age, country, type of study population, duration of intervention, and type of control group. The results showed that no other covariates were found to significantly modulate the intervention effect. For more detailed information, see Supplementary Table S4.

DiscussionSummary and interpretationDepression poses significant harm to both individuals and society. On the individual side, depression is characterized by low mood, loss of interest or pleasure, increased physical symptoms, impaired daily functioning, and increased risk of suicide (Grassi et al., 2023). On the societal side, depression leads to economic costs, diminished productivity and broken social relationships (Magalhaes et al., 2022). Therefore, there is an urgent need to investigate effective interventions to improve depressive symptoms. Our findings suggest that narrative therapy may be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. However, due to the limited number of studies on depression patients, further research is needed to determine the applicability of our results to individuals with pure psychological disorders like depression.

Our findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that narrative therapy has a significant impact on alleviating depressive symptoms and may reduce the occurrence of depressive symptoms. A published scoping review of the literature showed that narrative-based psychotherapy appeared to have a positive impact on mood symptomatology and other indicators. Participants who received narrative therapy showed improvements in depressive symptoms and general psychosocial symptoms and problems, including interpersonal relationships (Hawke et al., 2023). The results of another meta-analysis study suggest that narrative therapy may improve negative emotions such as psychological distress, anxiety, depression, and quality of life in cancer patients to some extent (Zhang et al., 2021). Given the very low quality of the evidence, there is uncertainty in our estimate of the effect. This uncertainty can be due to small sample sizes, variable study quality, or publication bias.

Two explanations have been proposed for this effect. On the one hand, some studies have focused primarily on improvements in insomnia disorders, pain control, or psychological resilience, whereas improvements in depressive symptoms were only a secondary outcome (Fang et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2021; Zhang & Wan, 2020). Thus, the intervention protocols used in these studies were not specific to depressive symptoms, which may have influenced the assessment of the effect of improvement in depressive symptoms. On the other hand, there is a lack of uniformity in the development of intervention protocols for narrative therapy, and variations in the duration and frequency of interventions in different studies may also affect the findings.

All interventions in this review were developed and guided by trained or experienced health professionals, psychotherapists, or narrative therapists, which is consistent with the results of other meta-analyses (Hawke et al., 2023). Taken together in this review and previous studies, we recommend that experienced professionals tailor and guide specific interventions for individuals when implementing narrative therapy.

Although there was a trend towards greater improvement in the adult group (mean age <65 years), the difference in effect sizes compared to the elderly group (mean age≥65 years) was not statistically significant. Therefore, we cannot conclude that there is a definite difference in the effectiveness of narrative therapy between these two age groups. However, further research with larger sample sizes and more refined age categorizations may help clarify if there are indeed age-related differences in the response to narrative therapy for depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. Moreover, older adults' diminished memory capacity can lead to difficulties in recalling and expressing experiences (Rhodes et al., 2019), poor concentration leading to difficulties in engaging in complete narratives (Salthouse, 2019), and diminished language skills affecting the ability to communicate and express emotions (Burke & Shafto, 2016). These factors may affect the efficacy of narrative therapy for older adults. In addition, the reduced learning ability of older adults may lead to slower acceptance of new approaches, which may affect the therapeutic effect. As for narrative therapy as a new exposure to older adults, this may be because older adults, when faced with new information and skills, may need more time and energy to adapt and assimilate them, and may also experience difficulties in memory and comprehension (Wolfe et al., 2023). Therefore, when designing treatment programs for older people, their learning characteristics and ability levels need to be taken into account. A more gentle, patient and individualized approach may need to be adopted to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of the treatment.

The finding that interventions of 6 to 12 weeks showed better outcomes is based on the subgroup analysis of intervention duration. In this analysis, we compared the effect sizes of narrative therapy on depressive symptoms for different intervention durations. We found that while all three groups (less than 6 weeks, 6 to 12 weeks, and greater than or equal to 12 weeks) had significant effects, the group with an intervention duration of 6 to 12 weeks had a relatively larger effect size, suggesting better outcomes. Narrative therapy, as postmodern psychotherapy, shows the potential to improve mood symptoms in depression over shorter periods. Given that prolonged treatment may exacerbate the risk of major depression, short-term treatment can be effective in preventing deterioration (Rush et al., 2009). Therefore, in the future, narrative therapy may be considered as an alternative treatment option that can be widely used in the early stages of depression in adults, especially during the period when mood symptoms are most active. Although our study did not examine significant interaction effects and simple slopes, future research could explore these aspects to further understand the relationship between intervention duration and depressive symptoms. This could provide valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of narrative therapy at different intervention durations and help optimize treatment protocols.

In the studies included in this meta-analysis, findings showed that narrative therapy was effective in alleviating depressive symptoms in adults with cancer, pregnant women, nurses, adult patients with stroke, adults with heart disease, adult patients receiving hemodialysis, adult patients with COPD, and adult patients undergoing bone and joint replacement. This demonstrates the effectiveness of narrative therapy on depressive symptoms across multiple intervention targets, which supports its broad applicability. Its ability to produce relief from depressive symptoms in diverse populations demonstrate its potential in the field of mental health. Narrative therapy is therefore equipped for dissemination and can be widely applied to a variety of adult populations to provide mental health support and assistance.

Publication bias can effect the conclusions of systematic reviews. Some researchers may consider the significance of the non-statistically significant studies to be small, choose not to publish, delay publication, or believe that publishing the negative results in full would reduce the value of the literature. However, the sensitivity analysis showed that the overall results were relatively stable, indicating that the authenticity of the study results was good and that publication bias had little effect on the results.

Strengths and limitationsThis meta-analysis provides an up-to-date review of the field, using a standardized framework, guidelines, and system of assessment tools. However, the study has several limitations. Firstly, the criteria set in this review resulted in the inclusion of numerous studies conducted in China. The conclusions therefore have limited generalisability to other geographical and cultural contexts. Future research should aim to investigate the use of narrative therapy in a more diverse range of populations. Second, the quality of the included studies varied, which may affect the accuracy of the conclusions. Therefore, more research is needed to explore the mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of narrative therapy and to develop more standardised intervention protocols. Finally, the existence of the possibility of unpublished studies or the occurrence of selective outcome reporting might result in a biased assessment of study effects.

ImplicationsBy evaluating the effectiveness of narrative therapy, this study provides practitioners in the healthcare system with substantive empirical support for using narrative therapy to improve patients' depressive symptoms. Also, our findings may provide valuable literature for practitioners to design narrative therapy intervention programs.

ConclusionThis comprehensive analysis found that narrative therapy appears to significantly reduce depressive symptoms in adults with somatic disorders. Narrative therapy was particularly effective among adults whose average age was less than 65 years. In addition, narrative therapy is effective in adult cancer patients, pregnant women, nurses, stroke patients, cardiac patients, hemodialysis patients, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, and adult patients undergoing bone and joint replacement. However, due to some limitations of the studies and the low quality of the evidence, large sample sizes, multicenter, long-term follow-up, and high-quality randomized controlled trials with "depressive symptoms" as the primary outcome indicator are needed to further evaluate the effectiveness of narrative therapy interventions in the future.

FundingThis research supported by the Educational Commission of Jilin Province of China (JJKH20231061KJ) and Jilin Association for Higher Education (JGJX2022B6).

CRediT authorship contribution statementGuannan Hu: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft, Data curation, Formal analysis. Bingyue Han: Methodology, Data curation, Formal analysis. Hayley Gains: Writing – review & editing, Investigation. Yong Jia: Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

None.

Author at:

These authors contributed equally to this work.

Guannan Hu, L.L.M.

School of Physical Education, Changchun Normal University, NO.677 Changji Street, Changchun, Jilin 130032, China.

Electronic address: 694564096@qq.com; Tel: +86 17767772953.

Bingyue Han, M.D.

School of Nursing, Jilin University, No.965 Xinjiang Street, Changchun, Jilin 130012, China.

Electronic address: 994053856@qq.com; Tel: +86 15847360860; ORCID: 0009–0008–7198–4947.

Hayley Gains, MSc

Department of Psychiatry, University of Cambridge, Clifford Allbutt Building, Cambridge Biomedical Campus, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0AH, UK.

Electronic address: hg440@cam.ac.uk; Tel: +44 01223 337 733.

- Descargar PDF

- Bibliografía

- Material adicional